Foraging for wild food is a world away from the trolley-push through the supermarket.

Those brightly-lit aisles barely cut it when you imagine gathering wild garlic in springtime, blackberries from late summer hedgerows, or sweet chestnuts as the tired old year begins to cool.

Clare Cremona wants to remind us how easy foraging for wild food can be, and it’s perfectly possible to start at home. “You would be surprised what is coming up on a bare patch of earth in your back garden,” she says.

And as an unusually mild winter slowly gives way to spring, she adds: “Right now there is actually quite a lot about. I think everything is coming out quite early, like pennywort, that is very good in a salad.”

Pennywort – the distinctive round leaves at their best and juiciest before flowers appear, usually in May – is just one of the wild foods she has chosen in the most recent of the Field Studies Council’s handy fold-out charts.

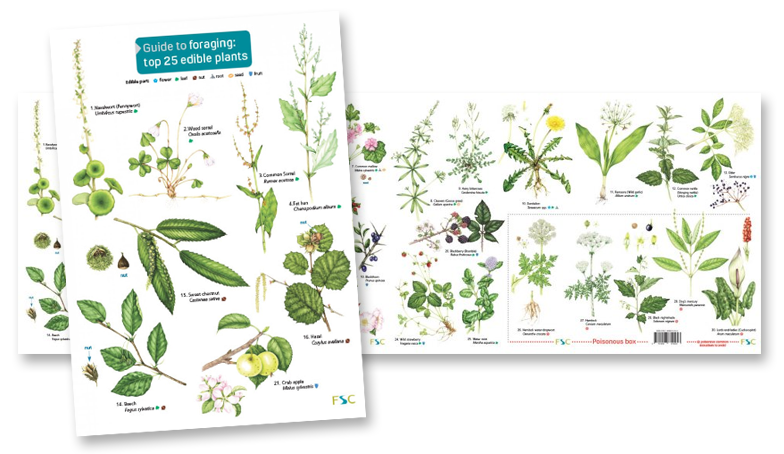

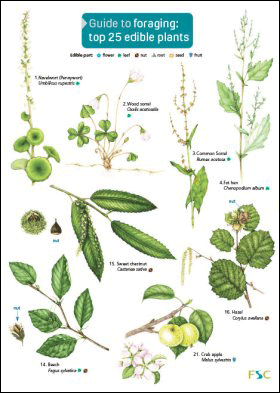

Guide to foraging: top 25 edible plants, written by Cremona, with illustrations by Lizzie Harper, highlights some of the easier wild foods to forage for, chosen to span most of the year.

“I agonised over the 25, that was the hardest thing,” she says. “Twenty-five is not very many, that took longer than actually writing it, deciding what to leave out.”

Among those that made the cut are common sorrel, one of the earliest green plants to appear in spring; jack-by-the-hedge, another harbinger of spring, which can be used to make a slightly garlicky sauce for lamb; wood sorrel, a woodland plant, once recommended by John Evelyn as suitable for the kitchen garden; fat hen, a very old food plant, its remains have been found at Neolithic settlements throughout Europe; and wild garlic, a good addition to salads and soups.

There are hints on when and where to look for each plant, identification notes, and suggested uses.

Several of the well known favourites that need no introduction are there, such as blackberry. As is the customary health warning – never eat any wild food unless you are absolutely sure you have identified it correctly.

Cremona includes a few poisonous plants that could be confused with the edible ones, such as hemlock water dropwort, extremely toxic and probably responsible for more fatalities than any other foraged food, and dog’s mercury, highly poisonous, common in woodlands, and easy to inadvertently pick with other foraged plants.

There is a conservation issue too. She advises only picking what you need, never uprooting a wild plant (an offence without the landowner’s permission under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981), and never pick a protected species, such as cowslip, even if you’ve found an old recipe book with the most tempting of recipes.

Cremona, a Forest School and Wildlife Watch leader for the Field Studies Council and Devon Wildlife Trust, says: “Generally people have a go and test something, people generally don’t strip the land of everything.

“For me it is far more important people know what they are seeing, if they don’t we are not going to look after them. And we are losing the knowledge of what you can and what you cannot eat.”

Which brings us neatly to cooking. Cremona makes her first nettle soup of the year at Easter time – it has become a family tradition – and includes a recipe for nettle soup here, and some others, including a mouth-watering wild garlic pesto.

A seasonal tradition in parts of the north of England is to make bistort pudding – sometimes called Easter-ledge pudding, dock pudding, passion pudding, or herb pudding – where foraged bistort leaves are cooked with onions, oats, butter and eggs, although recipes vary from place to place and sometimes other hedgerow leaves go into the mix.

The resulting partly-foraged and wholly distinctive savoury pudding is served as a side dish with lamb at Easter, or with bacon and eggs at other times. Competitions are held to find the best tasting, including the annual World Dock Pudding Championships, at Mytholmroyd, in the West Riding.

So perhaps this Easter is the time to have a go at foraging for wild food?

Guide to foraging: top 25 edible plants is available now from NHBS