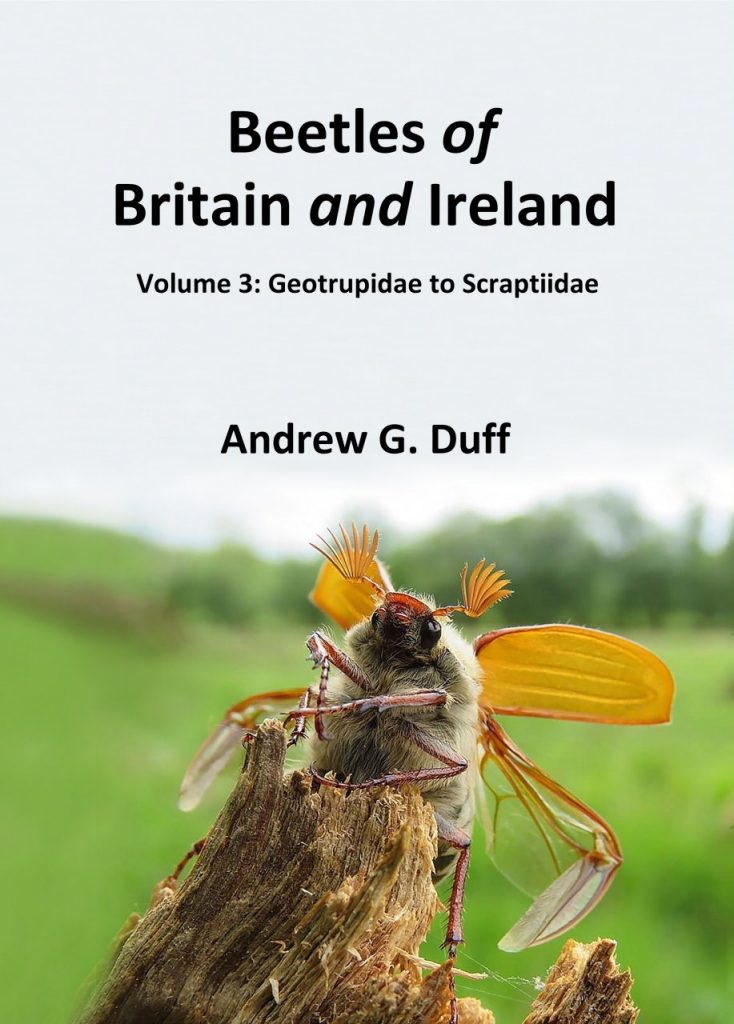

In our latest Q&A we talk to Andrew Duff, keen naturalist and author of the new book Beetles of Britain and Ireland Volume 3, which joins a monumental 4-volume identification guide to to the adult Coleoptera of the Republic of Ireland, the United Kingdom of Great Britain & Northern Ireland, and the British Crown Dependency of the Isle of Man. By bringing together reliable modern keys and using the latest taxonomic arrangement and nomenclature, it is hoped that budding coleopterists will more quickly learn how to identify beetles and gain added confidence in their identifications.

In our latest Q&A we talk to Andrew Duff, keen naturalist and author of the new book Beetles of Britain and Ireland Volume 3, which joins a monumental 4-volume identification guide to to the adult Coleoptera of the Republic of Ireland, the United Kingdom of Great Britain & Northern Ireland, and the British Crown Dependency of the Isle of Man. By bringing together reliable modern keys and using the latest taxonomic arrangement and nomenclature, it is hoped that budding coleopterists will more quickly learn how to identify beetles and gain added confidence in their identifications.

Andrew has taken his time to answer our questions about his book and about the fascinating world of beetles.

Aside from the most conspicuous species, beetles seldom seem to attract as much attention as some other insect orders. What is it that has drawn you to study this group?

My initial attraction to beetles was by coming across some of the larger and more colourful species, as you might expect. The first occasion was in about the late 1970s. I was out birdwatching with my oldest and best friend, the Ruislip naturalist Mike Grigson, when he found a species of dor beetle. These are large black beetles, often found wandering in the open on heaths and moors. They have the most striking metallic blue undersides. Picking one up, Mike said to me: “beetles are really beautiful ”, and I can still picture him saying it. The next occasion was when I was assistant warden at the Asham Wood reserve on the Mendip Hills in Somerset, in the summer of 1982. The warden, Jim Kemp, was an expert mycologist with a side interest in beetles. One day we were on the reserve and he pointed out a black-and-yellow longhorn beetle sat on an umbel. I thought it was very exotic-looking, every bit as worthy of a naturalist’s attention as butterflies and orchids! So I resolved to find out more about the beetles found in Asham Wood. Bristol Reference Library had a copy of Norman Joy’s Practical Handbook of British Beetles and it was obvious that I needed to buy it. Once I had my own copy of ‘Joy’, there was no stopping me. I started finding beetles and was able to identify most of them. The more you study beetles, the more you realise that all of them have their own special kind of beauty, and this is what ultimately led me to become a coleopterist. That, and the intellectual challenge of identifying small brown beetles, are what continue to inspire me.

What motivated you to write and publish Beetles of Britain and Ireland?

Joy’s Practical Handbook of British Beetles was the standard beetle identification guide for at least two generations of British coleopterists, ever since its publication in 1932. Joy’s book provided concise keys to every British beetle in a handy two-volume set, one volume of text and one of line drawings. The trouble with this idea is that the keys were oversimplified and misleading because of all the detail that wasn’t included. By the 1980s ‘Joy’ was already long past its ‘best before date’. Talk started about somebody producing a successor set of volumes and the late Peter Skidmore made a start—after his death I was fortunate to obtain his draft keys and drawings, and in particular have made much use of his drawings in my book. Peter Hodge and Richard Jones then published New British Beetles: species not in Joy’s practical handbook (BENHS, 1995). This was a fantastic achievement because it brought together in one place a list of the species not included in ‘Joy’, as well as notice of recent changes in nomenclature and of some errors in his keys. But it was still only a stop-gap measure.

By around 2008 still nothing had been produced by anyone else. I reckoned it might be achievable and began to discuss with other coleopterists the idea of writing a new series of volumes. The turning point was a discussion with Mark Telfer at a BENHS Annual Exhibition in London. My main concern was over the use of previously published drawings in scientific papers, but Mark reassured me that provided the drawings were properly credited and that the book was clearly an original work in its text and design then it should not fall foul of any copyright issues. By 2010 I’d already made a start on Beetles of Britain and Ireland and in the summer of that year took early retirement so that I could work on it more or less full time. My own professional background is as a technical author in the world of IT and from the 1980s onwards I’d had extensive experience of what used to be grandly called desktop publishing, what we would now call simply word processing! I’d decided to go down the self-publishing route so that I could ensure the production values matched what I thought coleopterists would want: a book which was laid out clearly and would stand up to a lot of wear. It’s really for others to judge whether my volumes meet the needs and expectations of most coleopterists, but so far I’ve been pleasantly surprised at how well they’ve been received.

How did production of this book compare to the previous volumes in the series? Was it difficult to bring together information on so many families exhibiting such a diversity of life histories?

As this is the third volume to have been completed I’d already learnt a lot about the best way to collate all of the material and summarise it, while trying to make as few mistakes as possible. The previous two volumes (vols. 1 and 4) were written in a rather erratic fashion, so that at any one time some sections would be more or less complete while others would not even have been started. This time I was determined to be more disciplined by starting with the first family, completing a draft which included the family introduction, keys to genera and species, and all of the line art illustrations, before going on the next family and doing the same again. In a way, having many families was an advantage because it meant I could use a ‘divide-and-rule’ strategy by breaking down a fauna of 1088 species into 69 smaller chunks. The fact that there are so many families in this volume didn’t generate any special problems, indeed families with only a few species like the stag beetles, glow-worms and net-winged beetles are relatively straightforward to document. But some of the family introductions were a challenge, insofar as some families are poorly defined taxonomically and hard to characterise in a way which would be accessible to amateur coleopterists. For example the darkling beetles (Tenebrionidae) exhibit a bewildering diversity which makes it well nigh impossible to say why a particular species is or is not assigned to this family. I made extensive use of the two-volume American Beetles (Arnett et al., 2002), which contains succinct summaries of nearly all of our beetle families, and this made my job a lot easier. But at the end of the day, the family diagnoses are not as important as the keys to genera and species. Most coleopterists won’t be coming to a particular family chapter as a result of methodically working through the key to families in volume 1. I imagine that in most cases people start by comparing their beetle with the colour plates, getting a shrewd idea as to what family it belongs to, and then going straight to the keys to genera and species. Picture-matching will always have its place in natural history, and I hope that Udo Schmidt’s 473 colour photos in this volume will be put to good use.

This volume covers some of our most familiar beetles – the ladybirds and chafers, for example. What advice would you give to anyone seeking to extend their interest beyond these well-known families to the more ‘obscure’ groups?

I would say that it largely depends on what kind of naturalist you are. What I mean by this is that there are two main ways of studying beetles, and you have to decide which path is right for you. On the one hand, many naturalists take photographs of beetles and by using the Internet or an expert validation service such as iRecord (www.brc.ac.uk/irecord/) they can usually achieve reliable identifications, at least to genus level, for medium-sized and large beetles. Some spectacular finds of beetles new to Britain have been found by general naturalists posting their images on the Internet, a very recent example being the flower-visiting chafer Valgus hemipterus, first posted to iRecord in April 2019 and already given the full works treatment in my volume 3. The problems start as soon as you try to identify smaller and more obscure beetles, because most of them are simply not identifiable from photographs. It’s not their small size and lack of bright colour patterns as such, so much as the need to view the underside, or the fore legs from a particular angle, or the head from the front, or the body orthogonally from directly above to ascertain the precise shape, which makes field photography impractical as a way to identify small beetles. So what you need to do is to go down the second path and start a beetle collection. This enables you to examine your specimen with a bright light source under a good stereomicroscope, turn it over to examine the underside, stretch out its legs to look for the pattern of teeth and spines, straighten it to measure its length and width, and if you’re feeling brave dissect out the genitalia which often provide the only definitive way to arrive at a species identification. Many naturalists balk at the thought of collecting beetles, but I would argue that the scientific value of having a comprehensive species list for a site outweighs any squeamishness I might feel about taking an insect’s life. In any case, my guilt is assuaged by the fact that insects are being eaten in their trillions every day, everywhere, by all manner of insectivorous animals and plants, so that the additional negative effect of my collection on beetle populations is vanishingly small.

Could you tell us a little about the process of compiling keys for the identification of the more challenging species? Were you able to draw upon the existing literature, or did you have to create them from scratch?

Some of the genera treated in this volume have been giving problems for coleopterists ever since the scientific study of beetles began. These are genera with a number of very similar, small and plain species that appear to have few distinguishing features. Nine genera in particular stand out for me as being conventionally ‘difficult’: Contacyphon, Dryops, Cryptophagus, Atomaria, Epuraea, Carpophilus, Meligethes, Corticaria and Mordellistena. It was always going to be a challenge for me to provide workable keys to these ‘nightmare nine’ genera, but I was keen to give it a go. It helps that I take a perverse interest in very difficult identification challenges, so I was motivated to come up with keys which would work. Fortunately I was able to pull together information from a variety of different sources until I had draft keys which could be put out for testing. The testing went through a number of iterations and by reworking the keys—for example adding my own illustrations, simplfying or reorganising couplets, or adding new couplets to account for ambiguous characters—they were gradually improved until I was happy with them. A second source of difficulty concerned the aphodiine group of dung beetles. The formerly very specious genus Aphodius was recently broken up into 27 smaller genera, and our leading dung beetle expert, Darren Mann, recommended to me that we should adopt the new taxonomy. This meant that I needed to construct a completely new key to genera, and that took a great deal of time and effort searching for characters. Incidentally I’d like to pay special thanks to Steve Lane and Mark Telfer for their advice and help with these difficult genera; I owe them both a great deal for their encouragement and support. The keys to challenging genera in this volume will certainly not be the last word on the subject, but I believe they are an improvement on previous keys.

When gathering information on habitat and biology of the various families, did you notice any glaring omissions? Are there any families that could particularly benefit from further study?

Some of the families treated in this volume are well understood, in terms of their identification, ecology and distribution in Britain and Ireland. The scarab beetle family-group, jewel beetles, click beetle family-group, glow-worms, soldier beetles, ladybirds, oil beetles and cardinal beetles are all popular groups and have been reasonably well studied, while the ladybirds have received a huge amount of attention! But that accounts for just 13 of the 69 families treated in volume 3, and the remaining 56 families are in general much less well known. Modern identification keys in English already existed for some of the other families but for most the information is very basic. I would say that the biggest gap in our understanding concerns the synanthropic and stored-product beetles. Not only do amateur coleopterists rarely come across these species, but the information that has been gathered (mostly by food hygiene inspectors) has not been made publicly available. In a few cases it’s not even clear which country a species has been found in, and all we know is that it has been found at some time, somewhere in Britain. I would like to think that this group will one day be much better documented.

A particular favourite of mine are the silken fungus beetles (Cryptophagidae). This family contains two of the ‘nightmare nine’ genera: Cryptophagus with 35 species and Atomaria with 44 species. I’ve tried hard to produce workable new keys for these two genera, but their identification is never going to be easy and it will be necessary to validate records for a long time to come. But I hope that at least this family will begin to benefit from a greater level of interest, on the back of my new keys.

There will be one more volume to come before this monumental series is complete – are you able to provide an estimation as to when that will come to fruition?

Volume 2 covers just one huge family: the rove beetles (Staphylinidae). This has been left until last for two good reasons. Firstly, the subfamily Aleocharinae, and in particular the hundreds of species in the tribe Athetini, are so poorly understood that it’s just not clear where the generic limits are drawn. This means I will have my work cut out trying to construct a new key to Aleocharinae genera. Preferably the key won’t involve dissecting out the mouthparts and examining them under a compound microscope, as we are expected to do now! Secondly, it has to be admitted that rove beetles are not the most exciting to look at. As publisher as well as lead author of my series of volumes it was always going to be difficult to sell a book which didn’t contain a lot of colourful plates. My plan all along, then, was to leave the rove beetles until last, in the hope that people would buy the book in order to complete their set! Volume 2 has already been started, and Udo has been working hard on the colour plates, but there is still a mountain to climb to complete the Athetini keys and illustrations to my satisfaction. My best estimate currently is that it will be published no later than 2024. Once that is done, and if I still have my wits about me, I suppose I’ll have to think about revised editions of the earlier volumes!

Beetles of Britain and Ireland: Volume 3 Geotrupidae to Scraptiidae

By: Andrew G.Duff

Hardback | Due July 2020| £109.00

Browse the rest of the Beetles of Britain and Ireland series on the NHBS website

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

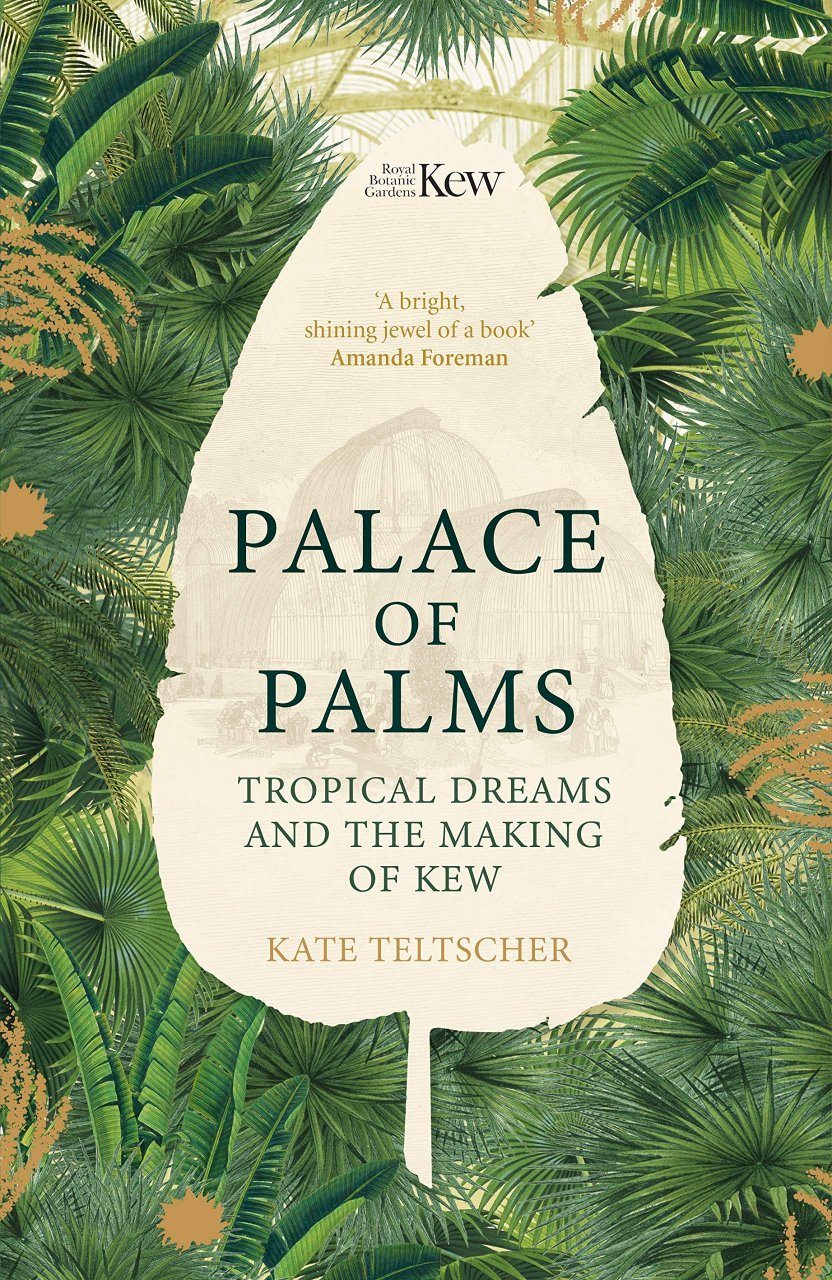

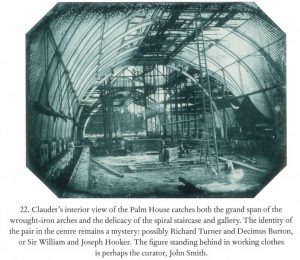

Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today

Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

Why were palms so important to the Victorians?

Why were palms so important to the Victorians? How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?

How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?

Ben Fitch is the national project manager for the

Ben Fitch is the national project manager for the

The Riverfly Partnership coordinates a number of projects looking at lots of different measurements of river health. These include surveying invertebrates, physical habitat, hydromorphological features and pollution events. What happens to the data that is collected in these projects? Who uses it and what for?

The Riverfly Partnership coordinates a number of projects looking at lots of different measurements of river health. These include surveying invertebrates, physical habitat, hydromorphological features and pollution events. What happens to the data that is collected in these projects? Who uses it and what for?

I would also like to share this beautiful image, simply named ‘Mayfly’, photographed by Jon Hawkins. This was the winning entry to the most recent RP Photography Competition and I think it deserves to be seen! (Reproduced with kind permission of the Riverfly Partnership, copyright Jon Hawkins.)

I would also like to share this beautiful image, simply named ‘Mayfly’, photographed by Jon Hawkins. This was the winning entry to the most recent RP Photography Competition and I think it deserves to be seen! (Reproduced with kind permission of the Riverfly Partnership, copyright Jon Hawkins.)

Tim Dee is a naturalist, radio producer, and author of

Tim Dee is a naturalist, radio producer, and author of

By travelling north you poetically write about the birds that come and go; from observing redstarts in Lake Lagano, Ethiopia, to enjoying the dawn chorus in a reedbed in Somerset. What can be learned from birds in migration, and how is migration changing for them?

By travelling north you poetically write about the birds that come and go; from observing redstarts in Lake Lagano, Ethiopia, to enjoying the dawn chorus in a reedbed in Somerset. What can be learned from birds in migration, and how is migration changing for them?

Stephen Moss is a naturalist, broadcaster, television producer and author. He is the

Stephen Moss is a naturalist, broadcaster, television producer and author. He is the

The Wren: A Biography

The Wren: A Biography

Wonderland: A Year of Britain’s Wildlife, Day by Day

Wonderland: A Year of Britain’s Wildlife, Day by Day Wild Hares and Hummingbirds: The Natural History of an English Village

Wild Hares and Hummingbirds: The Natural History of an English Village