There is a shortage of natural nesting sites for birds and this has played a part in the decline of some of the UK’s most iconic species. It’s easy to provide nesting opportunities for birds in our gardens and outdoor spaces, and with spring rapidly approaching, now is the ideal time to start thinking about nest boxes for your local birds ahead of the breeding season.

In this blog, we answer some of the most frequently asked questions about nest boxes – covering where and when to put them up, cleaning and maintenance, how to deal with predators and more.

When is the best time to put up nest boxes?

There really is no ‘best’ time to put up nest boxes. By putting up boxes in the autumn you can provide much needed winter refuges for roosting birds and possibly increase the chance of them staying and nesting there when spring comes around. However, any box erected before the end of February stands a good chance of being occupied if it is sited correctly. Even after February there is still a chance that they will be used; tits have been known to move in during April and house martins as late as July. Therefore, put your nest box up as soon as it is available rather than leaving it in the shed!

Where should I hang my nest box?

Locating your nest boxes correctly is one of the key determinants in how likely birds are to occupy them, therefore the ‘where’ is much more important than the ‘when’. Nest boxes must provide a safe, comfortable environment and protect the inhabitants from predators and the worst of the weather. This may be difficult to achieve; a safe location out of reach of predators may also be exposed to the weather, so have a good think before you start putting nails in.

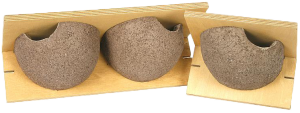

Nest boxes can be fixed to walls, trees or buildings, and there are an array of different styles of boxes that suitable for each location. Fixing to artificial surfaces means the growth of the tree does not have to be taken into consideration, which is useful for Schwegler and Vivara Pro nest boxes that can last for at least 20-25 years: a significant amount of time in the life of a small tree. If you’re planning any building work, remember that some bird and bat boxes can also be built directly into walls and roofs.

Locating boxes out of the reach of predators can be a challenge (weasels can climb almost anything), but there are things you can do to make it harder for them. Boxes in gardens should be located where cats cannot get to them, and prickly or thorny bushes can also help to deter unwanted visitors. Some nest boxes also have anti-predator designs (e.g. Schwegler’s 1N deep nest box). It is also best to avoid nest boxes that have a combined bird feeder and boxes should not be sited too close to the bird feeders in your garden. Visitors to the feeder may disturb the nesting birds and the feeder could attract unwanted attention from predators.

The height of the box is not crucial for many species, however, by placing it at least two metres off the ground you can help prevent predators and human interference. The direction of the entrance hole should be away from the prevailing wind and it is beneficial for there to be a clear flight path to the box. Crucially, the box should be also be sheltered from the prevailing wind, rain and strong sunlight, so in most UK gardens aim for a northerly, easterly or south-easterly aspect. If possible, position the box at a slight downward angle to provide further protection from the rain. There are a few species do have specific requirements for where a box should be sited (e.g. house martins and swifts nests need to be sited under the eaves); please see our product details for particular instructions for different species.

Wherever you position the box, try to ensure that you can still get access to it for maintenance. And finally, if possible, try to put it somewhere where you can see it, or invest in a nest box camera, so as to maximise your enjoyment of watching wild birds in your garden.

Is there anything else I can do to deter predators?

As already mentioned, location is the most important factor when trying to deter predators. Whilst some mammals can climb walls, a blank wall is fairly inaccessible so can be a good choice. Ensure that the box cannot be reached by a single jump from a nearby branch or the ground.

Box design can also help deter predators. An entrance hole reinforced with a metal plate will prevent grey squirrels and some avian predators from enlarging the hole and gaining access to the nest. Woodcrete and WoodStone boxes are too hard for any predator to break through. However, you can also reinforce a nest box yourself with metal protection plates or provide additional protection with prickly twigs. Deep boxes may prevent predators reaching in and grabbing nest occupants, although some tits have been known to fill up deep boxes with copious quantities of nesting material. If you’re using an open-fronted nest boxes, a balloon of chicken wire over the entrance can work well. If you live in an urban area, cats are likely to be the most common predator. Gardeners have long since used various methods to exclude these unwanted visitors, such as pellets and electronic deterrents, all with varying degrees of success.

How do I manage the nest box?

A well-designed nest box will only need one annual clean in the autumn. It is important not to clean out nest boxes before August as they may still be occupied. Wait until autumn and then remove the contents, scattering them on the ground some way from the box to help prevent parasites re-infesting the nest box. Wear gloves and use a small brush or scraper to remove debris from the corners. Boiling water can be used to kill any parasites remaining in the box, but remember to leave the lid off to dry out fully. Do not wait until the winter to clean out nest boxes as birds may already be roosting in them. The tit species do a thorough clean out of any old nesting material or roosting debris before they begin nesting again, but it will save them energy if you can help out.

How many nest boxes do I need?

The exact amount of boxes required will depend on the space available, species and the surrounding habitat. As a very general rule of thumb, start with ten assorted small boxes per hectare (ensure uniform spacing between boxes). Keep adding several more boxes each season until some remain unused and hopefully you’ll hit on the correct density of boxes. However, even if you only have space for one box it is still worthwhile, providing it is suitably located, as many UK bird species need all the additional nesting habitat they can get.

You can browse the full range of nest boxes we sell online and, if you’re keen to find out more, check out the BTO Nestbox Guide, which is packed with essential information.

If you are interested in installing a nest box camera into one of your bird boxes, take a look at our “How to choose the right nest box camera” article for more information on choosing the model that’s right for you.

Further information about individual nest boxes, including advice on positioning, can be found alongside each nest box in our range. If you have any other questions or would like any further advice, then please get in touch with our team of Wildlife Equipment Specialists.

The society was named in honour of John Ray (1628 – 1705), an eminent British natural historian. Ray was born in Essex and educated at Cambridge University. He published numerous works on botany, zoology and natural theology and his theories and writings are widely recognised as laying the foundations for the later works of both Linnaeus and Darwin.

The society was named in honour of John Ray (1628 – 1705), an eminent British natural historian. Ray was born in Essex and educated at Cambridge University. He published numerous works on botany, zoology and natural theology and his theories and writings are widely recognised as laying the foundations for the later works of both Linnaeus and Darwin.

Mary Colwell is an award-winning writer and producer who is well-known for her work with BBC Radio producing programmes on natural history and environmental issues; including their Natural Histories, Shared Planet and Saving Species series.

Mary Colwell is an award-winning writer and producer who is well-known for her work with BBC Radio producing programmes on natural history and environmental issues; including their Natural Histories, Shared Planet and Saving Species series.

Carlos Magdalena is a botanical horticulturist at Kew Gardens, famous for his pioneering work with waterlilies and his never-tiring efforts to save some of the world’s rarest species from extinction. In his book,

Carlos Magdalena is a botanical horticulturist at Kew Gardens, famous for his pioneering work with waterlilies and his never-tiring efforts to save some of the world’s rarest species from extinction. In his book,

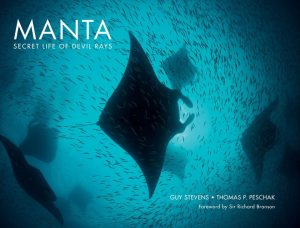

Your life as a researcher and CEO of the Manta Trust must be incredibly varied and exciting. I’m curious what a typical day in the life of Guy Stevens looks like. Or, if a ‘typical’ day is unheard of for you, can you describe a recent day for us?

Your life as a researcher and CEO of the Manta Trust must be incredibly varied and exciting. I’m curious what a typical day in the life of Guy Stevens looks like. Or, if a ‘typical’ day is unheard of for you, can you describe a recent day for us?