What is Biodiversity Net Gain?

Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) is a new scheme from the government which requires that all new developments improve the natural environment rather than degrade it. From November 2023 onwards, new developments must make sure that the habitat for wildlife is in a better position than it was before the development.

The developer must try to avoid any loss of habitat in the land that is being developed. If this is not possible, additional habitat must be created, either on-site or off-site; at an alternative area that the developer owns, by purchasing units from a land manager or by buying statutory credits from the government. A combination of all three options can be used to make up BNG, but approval from local planning authorities must be gained.

Who will be affected by this new scheme?

The main people who will be impacted by this new scheme are:

- Land managers

- Developers/construction

- Local Planning Authorities

- Ecologists

If you own or manage land in England, you can get paid by selling biodiversity units to developers. Currently, the new scheme will only cover England, although existing regulation in Wales requires developments to provide a net benefit for biodiversity. Within Scotland, the 2019 Planning Act requires developments to provide positive impacts for biodiversity.

How much gain is needed?

Under the Environment Act 2021, all new developments need to deliver at least a 10% net gain, with the habitats needing to be secure for at least 30 years. These areas must be either delivered on-site, off-site or via the new statutory biodiversity credits scheme. A national register will hold records and information of all net gain delivery sites.

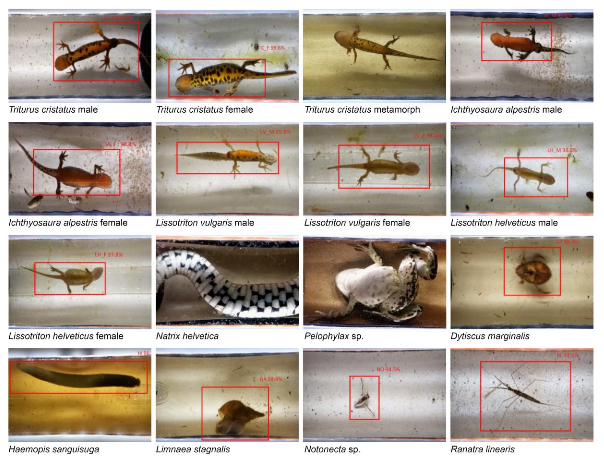

How is this measured?

An area will be assessed based on its value to nature so that developers or land managers can understand the biodiversity value of a site. The biodiversity metric can be used to assess the value of the land, demonstrate biodiversity gains or losses, measure direct impacts on biodiversity and compare proposals for creating or enhancing habitats on- or off-site. Creating a consistent approach to biodiversity assessment will help planning authorities and communities to better understand the impacts that development can have on the natural environment and to provide the necessary monitoring to ensure that environmental improvements and mitigations for habitat loss are effective.

The metric will calculate the value of a site as ‘biodiversity units’, which are based on the size of the habitat, its quality or condition and location, including whether the sites are in locations identified as local nature priorities. For example, each habitat condition is assessed based on certain criteria, including essential criteria that must be met to achieve a good condition score. The condition is then scored as either poor, moderate or good. Other factors that affect the biodiversity value include how connected the habitat is with other areas and the rarity or diversity of the habitat and the species found in it.

There have been multiple versions of the biodiversity metric, starting in 2012 when the first metric was piloted. With each new version, changes have been made based on suggestions put forward by experts. Currently, biodiversity metric 3.1 is being used, but the government is advising that a future biodiversity metric 4.0 will be Defra’s standard from November 2023. The calculation tools and user guides can be found on Natural England’s Access to Evidence website.

Once the values are obtained, the developers must deliver a biodiversity gain plan, setting out how the development will deliver this net gain and allowing planning authorities to assess whether the proposals meet objectives. The plan should cover:

- how any adverse impacts on habitats will be minimised,

- the biodiversity value of the onsite habitat pre- and post-development,

- the biodiversity value of any offsite habitat,

- if any statutory biodiversity credits will need to be purchased,

- any further requirements set out in other legislations.

How will this impact the environment in England?

Development, land-use change and urban expansions are among the leading causes of biodiversity loss. The UK is one of the most depleted countries, having lost nearly half of our biodiversity since the 1970s. We are ranked in the worst 10% globally for biodiversity intactness. Overall, 41% of species in the UK have declined, with 26% of mammals at risk of extinction. We’ve lost 97% of our meadows, 90% of our wetlands and 80% of lowland heathlands. A scheme where development will no longer lead to biodiversity loss, but instead to net gain, is a step in the right direction to preventing further loss and helping to begin repairing our degraded environment.

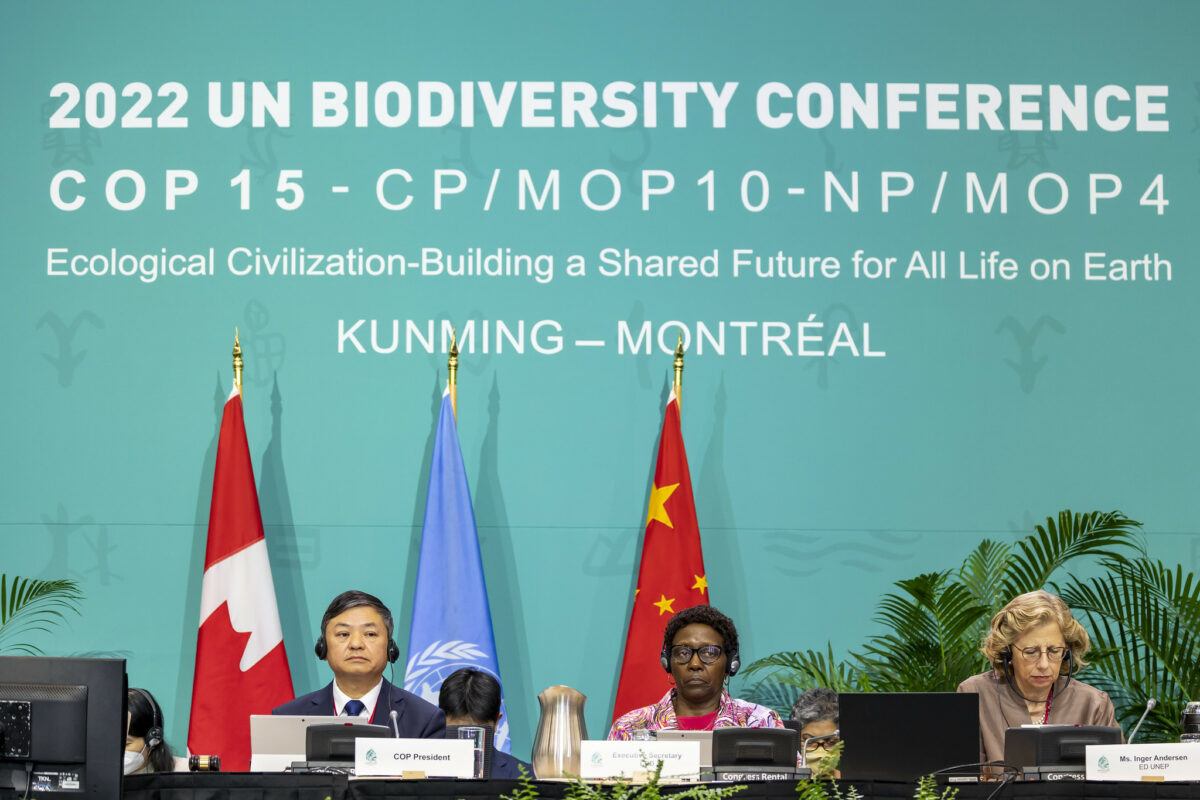

Replacing any established habitats with new ones, however, will have a temporary negative impact on the environment, as newly created habitats can take years to be properly established. This would mean a short-term loss in biodiversity which may have serious consequences for vulnerable species. This is essentially the same issue with COP26’s Declaration on Forest and Land Use, which does not actually forbid the cutting down of forests, but rather aims to end net deforestation, with forest loss being replaced “sustainably”. However, replacing primary or old-growth forests with new growth has serious negative environmental consequences, as the highly complex ecosystems supported by old-growth forests have an irreplaceable value.

There is hope, however, as the Environment Act includes provisions which will exempt irreplaceable habitats from the BNG requirement, as the National Planning Policy Framework states that “development resulting in the loss or deterioration of irreplaceable habitats…should be refused, unless there are wholly exceptional reasons and a suitable compensation strategy exists”. This, therefore, will prevent the new scheme from weakening existing protection for these irreplaceable habitats such as ancient woodlands.

Most important, however, is the need for accurate monitoring to ensure that the pre- and post-development biodiversity values are accurate. A recent report has shown that HS2 Ltd has been undervaluing existing nature and overvaluing its compensation measures, with biodiversity loss from Phase 1 of HS2 being at least 7.9 times higher than calculated, and loss caused by Phase 2a 3.6 times higher. The report found that habitats such as watercourses, ponds and trees had been completely missed out from the data and habitats such as well-established tree-lined and species-rich hedgerows have been valued lower than the new hedgerows HS2 Ltd is planning to plant. Inaccurate reporting will undermine the main aim of the BNG scheme, reducing its effectiveness and continuing the degradation of biodiversity in England.

What are the barriers?

There are several issues which may impact the successful implementation of this new method. The first is a lack of resources within local authorities. All new biodiversity gain plans must be approved by local authorities to make sure they are accurate and meet the correct objectives, therefore there must be someone with ecological expertise within the local planning authorities who can review applications and oversee the delivery of these plans. Additionally, local planning authorities may not be able to identify and set up off-site compensation measures needed if a net gain cannot be produced on-site.

Additionally, a lack of clear information, awareness or training for developers, land owners/managers, planning authorities and farmers is another barrier to the success of this method. If those involved are not given access to the correct training, it is unlikely that BNG will be implemented successfully, delaying developments and putting our environment at continued risk. A further issue includes cost implications, as delivering BNG will involve an extra cost that will need to either be absorbed by developers or passed onto customers. However, the scheme will open a new market for landowners, helping to provide environmentally positive incomes.

There has also been criticism about how the previous iterations of the biodiversity metric classified habitats. Scrubby landscapes, such as those dominated by bramble and ragwort, were classed as a sign of degradation, despite them being key features of many rewilding projects. Certain plants, such as docks, were considered ‘undesirable’ despite being a key food plant for many insect species. Due to these classifications, these areas might not be properly compensated for, meaning that the net gains planning would be inaccurate.

Summary

- From November 2023, all new developments must deliver a 10% biodiversity net gain, either through on- or off-site plans or by purchasing statutory credits.

- The biodiversity value of the habitats on the development site must be determined using the Biodiversity Metric 4.0, which should be released in Spring 2023.

- This scheme will help to reduce biodiversity loss and begin to repair the environment in England, but only if it is properly implemented and enforced.

- A lack of funding, awareness and training could be barriers to the successful implementation of this scheme. Other issues such as additional costs and poor habitat classifications are also risks to success.

Resources

The government website on Biodiversity Net Gain.

The government website on the Net Deforestation pledge.

Report by The Wildlife Trusts on the accuracy of HS2 Ltd’s biodiversity value reporting.

A news report on the criticism surrounding how certain habitats have been classified.