Research

15-million-year-old giant wombat skeletons have been uncovered in Australia. A new paper analysed the various features of these fossil bones to reveal the overall size and shape of the animal, its lifestyle and surrounding environment, as well as what kind of movements the animal was capable of. The research showed that this species, known as Nimbadon, spent some of its time suspended from tree branches like a sloth, grew in periodic spurts and had opposable thumbs. They are currently studying the enamel microstructure of Nimbadon’s teeth to determine its diet.

A program to plant 20 million trees in Australia prioritised cost-saving over gains for the environment, according to new research. Beginning in 2014, the program was aiming to improve native vegetation, support a richness of plant and animal species and reduce greenhouse gases. However, funding decisions were largely driven by ‘value for money’ considerations, with projects where the cost per tree was less than A$5 far more likely to be funded than projects where a tree cost more than A$10, undermining the benefits for both threatened species and the climate.

Extinction risk

A lack of large prey in Nepal may be the reason behind the rise in human-tiger conflicts. The wild tiger population has nearly tripled in the past 12 years but this has led to an increase in conflicts, with tigers in Bardiya National Park frequently preying on livestock in nearby settlements. Tigers in Parsa National Park, however, have access to large prey such as wild water buffalo and guar wild cattle, and researchers found no traces of livestock in their diet.

Trapping is holding back the speed of bird recovery in the Harapan Forest, Sumatra, Indonesia. A new study has found that the decade of protection and natural regeneration has helped bird populations increase in this forest, but wild trapping is preventing the full results of reforestation efforts. 45.1% of 122 bird species showed a notable population increase from 2009 to 2018, but 16.2% faced intensified trapping pressure.

Climate change

For the first time, wind is now the main source of UK electricity. In the first three months of 2023, wind turbines generated more electricity than gas, with a third of the country’s electricity coming from wind farms. There was also a record period for solar energy generation. While there is still a long way to go, this is a step in the right direction to meet the UK’s aim for all its electricity to have net zero emissions.

Frogs in Puerto Rico are croaking at a higher pitch due to global heating. The coqui frog appears to be decreasing in size due to the warmer temperatures, which is causing their croaks to become more high-pitched. Researchers are warning that if the trends continue, the temperature could become too high for certain amphibians to survive.

A new report claims that the UK could unlock £70bn a year in renewable energy. Generating more green electricity to meet the UK’s climate targets could create an additional 279,000 jobs, supporting a total of 654,000 jobs. If Britain’s clean electricity generation increased 50% above its current projections for 2050, it could be capable of exporting £17bn of green electricity to Europe annually. This could attract trillions in global private investment, doubling the £35bn a year economic benefit forecasted for its current path. To do this, government policymakers must remove barriers hampering the UK’s green energy ambitions, such as making sure the UK has enough batteries to store its renewable electricity and retrofitting commercial buildings to improve the UK’s energy efficiency.

Conservation

A Cornish farm is launching a project to triple the UK’s temperate rainforest. The Thousand Year Trust is being launched this year by a veteran who is now transforming his 120-hectare hill farm on Bodmin Moor into the largest rainforest restoration project in England and Wales. Working with local farmers, landowners and other charities to identify land suitable for this habitat, the charity has the ultimate aim of tripling Britain’s surviving rainforest to 1m acres over the next 30 years.

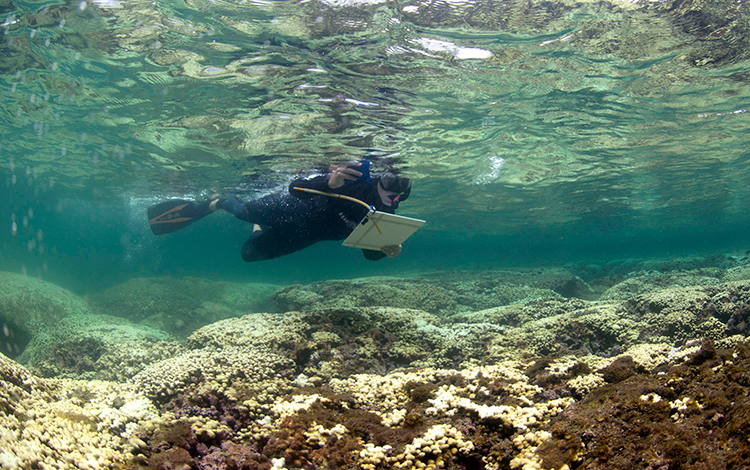

Seabird conservation is mostly working, according to a comprehensive new data set. Researchers compiled a data set of 851 seabird restoration events over the last 70 years, spanning 551 locations and targeting 138 seabird species. Forty-nine events used translocation, while 802 used social attraction, such as decoys, bird sound recordings and other devices aiming to lure birds to a new place. While the result of each project depended largely on the species and circumstances, most were successfully completed.

Policy

An unprecedented €2.2bn drought response plan has been approved in Spain. The package of measures includes €1.4bn in funds to tackle the drought and increase water availability, and €784m to help farmers maintain production and avoid food shortages. The €1.4bn will be spent on building new infrastructure, such as desalination plants, doubling the proportion of water that is reused in urban areas from 10% to 20% by 2027, and subsidising those whose irrigation water supplies would be reduced.

Experts are calling for a ban on importing foreign soil to the UK, to help save British wildlife. Imported plants, soils and compost can be a vector for invasive, non-native species, including insects, microorganisms and seeds, which could outcompete native species. 356,000 tonnes of plants and soils were imported during 2021, creating a significant threat to our ecosystems.