With the recent arrival of Autumn, the fungi season is now upon us. And so, NHBS is delighted to announce Geoffrey Kibby as our Publisher of the Month for October.

Geoffrey Kibby is one of Britain’s foremost experts on identifying mushrooms in the field, and his privately published books on how to identify British mushrooms pass on many of those skills. Kibby’s user-friendly books contain an enormous amount of information, are fully illustrated and are aimed at everyone, from the fungi enthusiast to the expert mycologist. The wealth of detail includes vital features to look for when identifying wild mushrooms and the important identification characteristics when using a microscope, often an essential tool in mycology.

Geoffrey Kibby is one of Britain’s foremost experts on identifying mushrooms in the field, and his privately published books on how to identify British mushrooms pass on many of those skills. Kibby’s user-friendly books contain an enormous amount of information, are fully illustrated and are aimed at everyone, from the fungi enthusiast to the expert mycologist. The wealth of detail includes vital features to look for when identifying wild mushrooms and the important identification characteristics when using a microscope, often an essential tool in mycology.

These books are also an essential guide to identifying edible mushrooms and are valuable handbooks when mushrooming anywhere in western Europe.

We asked Geoffrey to tell us about how he originally became interested in mycology, and what he hopes to achieve with his wonderful books:

I was 13 when I first became aware of fungi: an intensely violet toadstool, unlike anything I had ever seen (Laccaria amethystina) and from that moment, I was hooked. I bought my first little mushroom guide, then another and another and more through the years until my bookshelves started to groan under the weight of books about fungi. Now, more than 50 years later, I am writing my own books, trying to produce the sort of works that I would have wanted as an aspiring young mycologist. My books are based on my years in the field, hopefully capturing the essence of each species. I have also made a conscious point of illustrating species not readily available in other guides and trying to give the most up-to-date names in what is an ever-changing science. Mycology is an inexhaustible field of study at whatever level your interest lies. With over 4000 species of larger fungi in Britain, you will never run out of species to find or new facts to discover.

I was 13 when I first became aware of fungi: an intensely violet toadstool, unlike anything I had ever seen (Laccaria amethystina) and from that moment, I was hooked. I bought my first little mushroom guide, then another and another and more through the years until my bookshelves started to groan under the weight of books about fungi. Now, more than 50 years later, I am writing my own books, trying to produce the sort of works that I would have wanted as an aspiring young mycologist. My books are based on my years in the field, hopefully capturing the essence of each species. I have also made a conscious point of illustrating species not readily available in other guides and trying to give the most up-to-date names in what is an ever-changing science. Mycology is an inexhaustible field of study at whatever level your interest lies. With over 4000 species of larger fungi in Britain, you will never run out of species to find or new facts to discover.

Browse Geoffrey Kibby’s entire range below, including the fantastic Mushrooms and Toadstools of Britain & Europe series.

Mushrooms and Toadstools of Britain & Europe, Volume 3: Agarics, Part 2

Hardback | £41.99

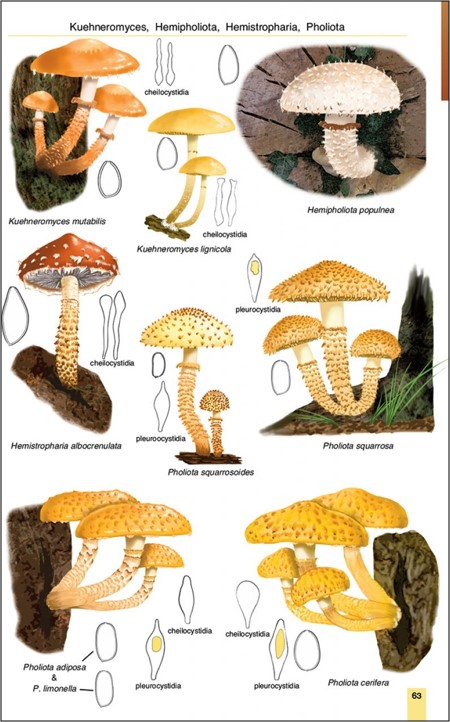

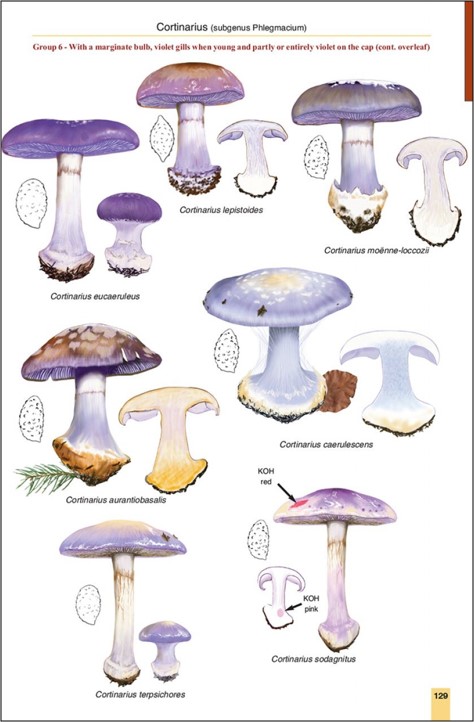

Volume 3 is the second to cover agarics in which over 680 common and rare species are covered, containing photographs and paintings to highlight important characteristics, including microscopic features.

Mushrooms and Toadstools of Britain & Europe, Volume 2: Agarics, Part 1

Hardback | £41.99

A total of 750 species and varieties illustrated with a key to major groups, dealing with the mainly white-spored agarics. The introduction to each section includes photographs, as well as useful illustrative paintings to highlight important characters that are sometimes difficult to ascertain from a photograph.

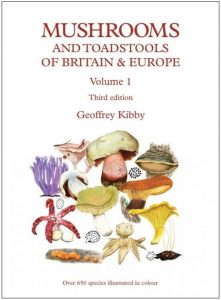

Hardback | £44.99

Volume 1 illustrates the non-agarics, including puffballs, stinkhorns, earthstars, coral fungi, polypores, crust fungi, chanterelles, tooth fungi, boletes, Russula and Lactarius. A total of 650 species are illustrated via watercolour paintings, along with drawings of the spores and other useful microscopic features.

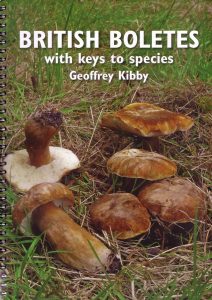

British Boletes: With Keys to Species

Spiralbound | £22.99

Boletes are some of the most popular fungi around the world, both because they are often choice edibles and because of their frequently exotic colours and large size. There are approximately 80 species in Britain and British Boletes provides user-friendly identification keys and descriptions to all the known species, along with colour photos of the majority of species.

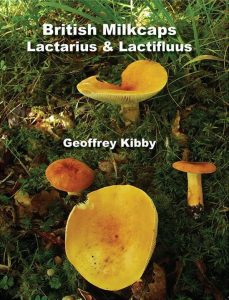

British Milkcaps: Lactarius & Lactifluus

Spiralbound | £22.50

The Milkcaps, the species of Lactarius and Lactifluus, are a popular group of fungi distributed throughout the world and with over 70 species in Britain. This guide presents colour photographs of all these species, many with highly detailed photos of their spores, readily accessible keys and up-to-date information on their distribution and ecology.

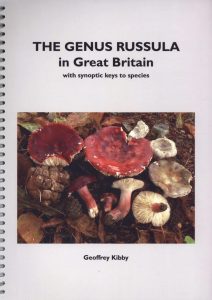

The Genus Russula in Great Britain: With Synoptic Keys of Species

Spiralbound | £26.99

This guide provides an easy-to-use keying system to identify the nearly 160 species of the genus Russula found in Great Britain. Each species is fully described, including a further 29 from Continental Europe and Scandinavia that have not yet been found here but might be expected to, with over 120 full-colour photographs provided.

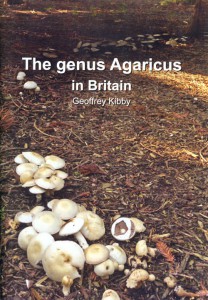

The Genus Agaricus in Britain

The Genus Agaricus in Britain

Paperback | £19.99

This guide describes all of the known British species in the genus Agaricus and provides easy to use synoptic/pictorial keys to the species and includes over 50 photographs illustrating the majority of British species

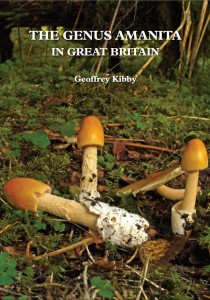

The Genus Amanita in Great Britain

The Genus Amanita in Great Britain

Paperback | £19.99

This guide presents a broad view of the British species in the genus Amanita, plus some extra-limital species that might be found here. It contains photographs of many of the commoner species and some of the rarer and more obscure species that are normally rarely shown.

The Genus Tricholoma in Britain

The Genus Tricholoma in Britain

Paperback | £16.99

This guide provides identification keys to the species of the genus Tricholoma known in Britain, plus others from mainland Europe which may be found here in the future. Full descriptions and discussion of the species are provided along with nearly 60 full-colour photographs of the majority of the British species.

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

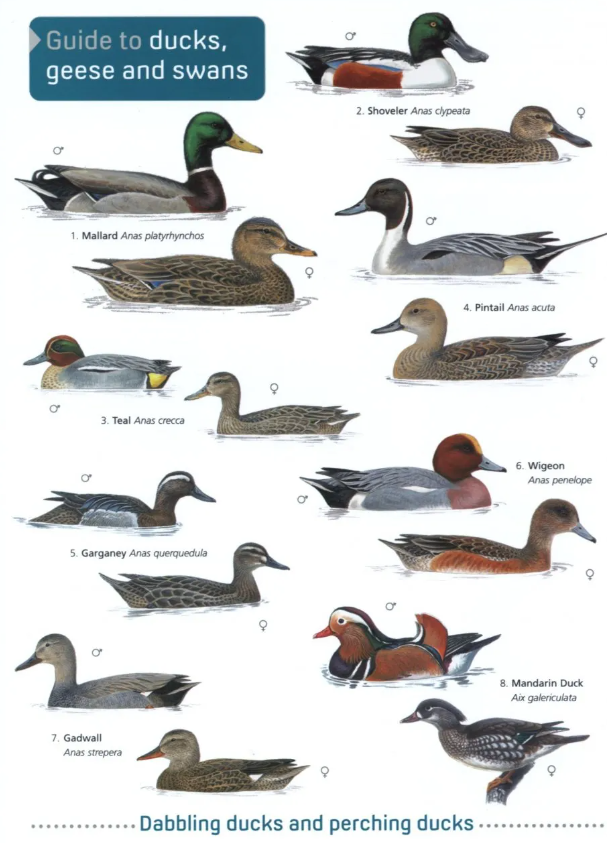

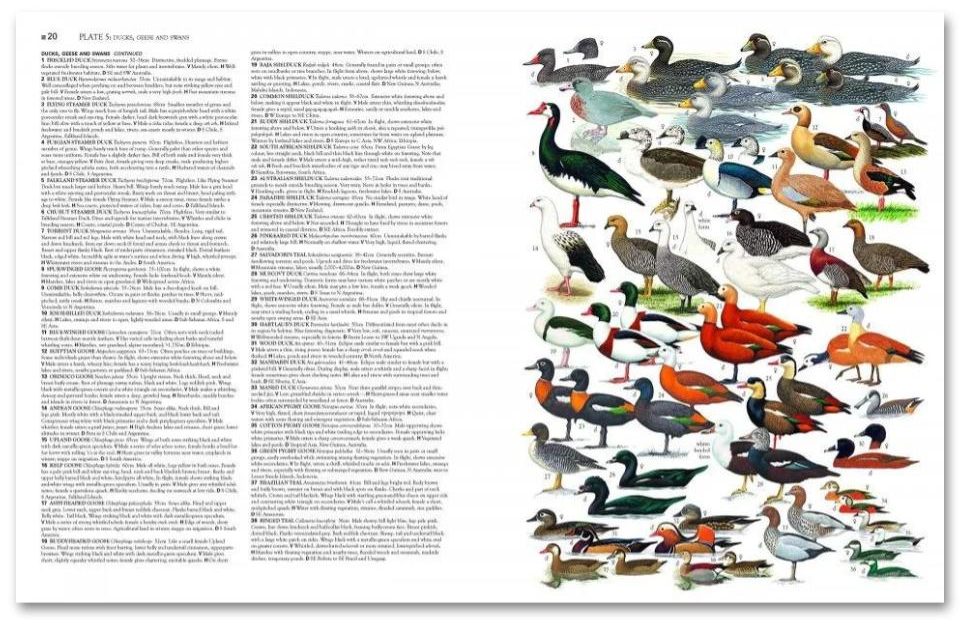

Guide to Ducks, Geese and Swans

Guide to Ducks, Geese and Swans  RSPB Spotlight: Ducks and Geese

RSPB Spotlight: Ducks and Geese

I originally trained as a mechanical engineer but ‘jumped ship’ in the 70s to take up my real love as a wildlife artist, with a focus on birds. I made this leap with much encouragement from my wife Marie and a great deal of help and inspiration from well-known bird artist Robert Gillmor, bird photographer Eric Hosking and the great East African ornithologist John Williams. I had no intention of working on book illustrations, but I got caught up in it, really liked it and I have enjoyed it ever since.

I originally trained as a mechanical engineer but ‘jumped ship’ in the 70s to take up my real love as a wildlife artist, with a focus on birds. I made this leap with much encouragement from my wife Marie and a great deal of help and inspiration from well-known bird artist Robert Gillmor, bird photographer Eric Hosking and the great East African ornithologist John Williams. I had no intention of working on book illustrations, but I got caught up in it, really liked it and I have enjoyed it ever since.

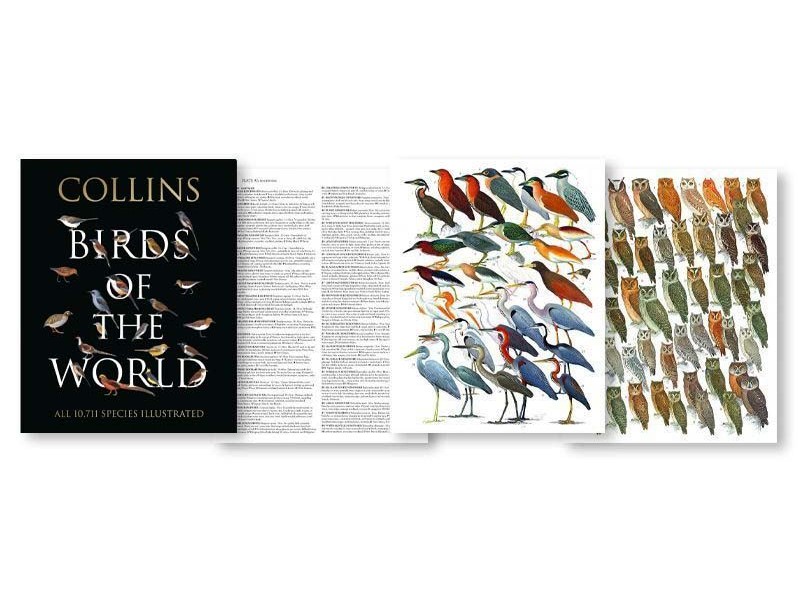

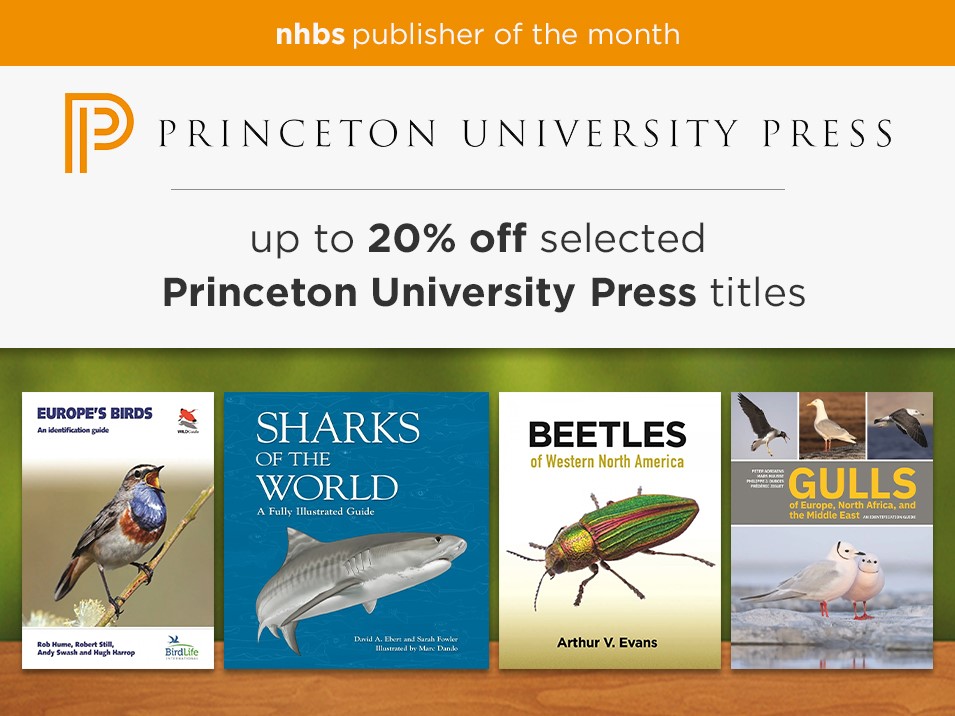

Princeton University Press was founded in 1905 as a nonprofit publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Originally publishing university documents and newspapers, such as the Princeton Alumni Weekly, Princeton University Press didn’t publish its first book until 1912. Since then, they have published over 21,000 works, including many award-winning titles. Princeton University Press publishes well-known series such as WILDguides, the high-quality, practical guides to many wildlife regions around the world, and Princeton Illustrated Checklists, which contain illustrations and concise text of all species in specific regions. They also publish and distribute Wild Nature Press, a natural history publisher that specialises in books on marine life.

Princeton University Press was founded in 1905 as a nonprofit publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Originally publishing university documents and newspapers, such as the Princeton Alumni Weekly, Princeton University Press didn’t publish its first book until 1912. Since then, they have published over 21,000 works, including many award-winning titles. Princeton University Press publishes well-known series such as WILDguides, the high-quality, practical guides to many wildlife regions around the world, and Princeton Illustrated Checklists, which contain illustrations and concise text of all species in specific regions. They also publish and distribute Wild Nature Press, a natural history publisher that specialises in books on marine life.

Plant Galls of the Western United States

Plant Galls of the Western United States