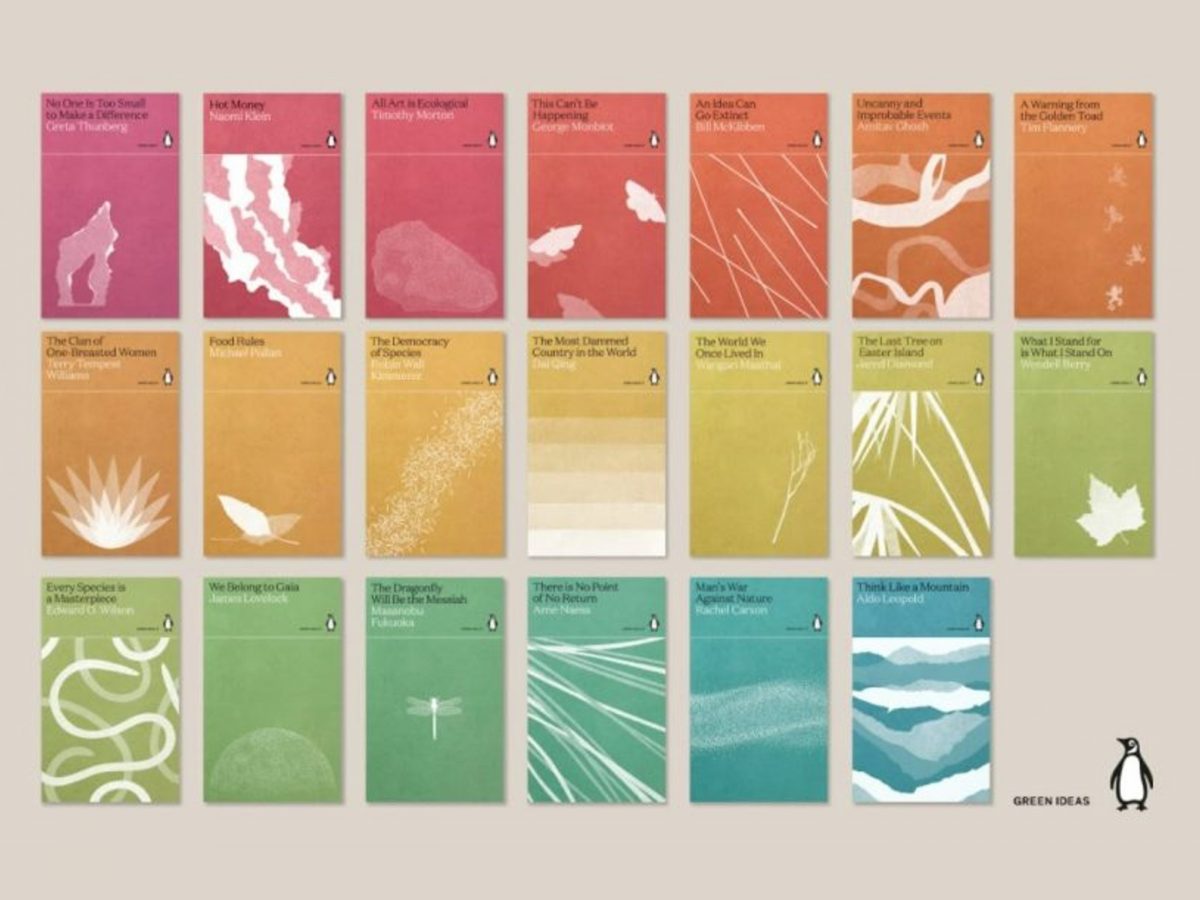

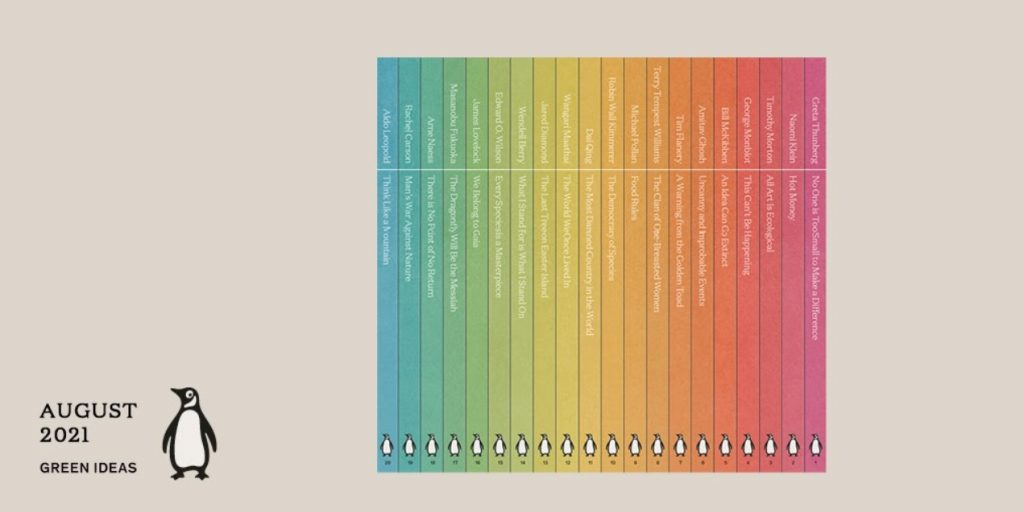

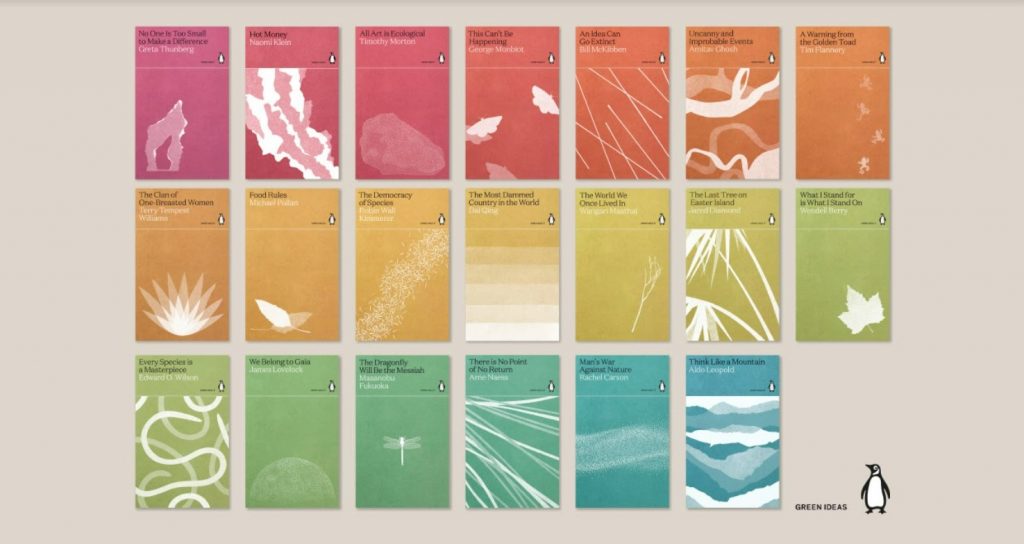

This August, Penguin Classics will launch their new series: Green Ideas. Featuring authors such as Greta Thunberg, Rachel Carson and Tim Flannery, Green Ideas brings together key environmental voices, classic and contemporary, who are advocating for change to the way we view our living planet. Exploring a wide-range of topics, from art to economics and almost everything in between, this twenty book series highlights the most important environmental issues of our time, while seeking to broaden our collective understanding of our environment.

Ahead of publication, Series Editor Chloe Currens has very kindly agreed to answer some of our questions below.

The Penguin Green Ideas series will make for wonderful additions to the recent influx of books on climate change and the environment. Could you tell us a bit about where the idea for the series originated?

Our former publicity director came up with the idea for the series in the wake of the publication of Greta Thunberg’s No One is Too Small to Make a Difference. Thunberg had managed to raise the temperature of the global conversation – we were suddenly talking about ‘the climate and ecological crisis’, about a house on fire, rather than gesturing to a milder vision of ‘climate change,’ which, if it was a threat at all, was somewhat obscure, or distant. The suggestion was that Thunberg was one of a line of great environmental thinkers, each of whom had made a similarly profound contribution to our understanding of the living planet. From our current vantage point, we could look back on the seventy-odd years of modern environmentalism and identify those key figures. Together they would form a new canon, and so it made sense to bring the series into Penguin Classics.

A fantastic array of important authors have been featured in the series. How did you approach decision-making when selecting excerpts?

The overall aim of the series was to draw out the emerging environmental canon, following it from its modern origins – roughly, Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which exploded into public consciousness in the sixties – through to the present day, with major, agenda-setting works by Naomi Klein, Amitav Ghosh, George Monbiot, and others. A variety of subjects naturally followed, and so the series covers everything from art and literature to economics and geopolitics, though there is a guiding concern with sustainability throughout.

The overall aim of the series was to draw out the emerging environmental canon, following it from its modern origins – roughly, Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which exploded into public consciousness in the sixties – through to the present day, with major, agenda-setting works by Naomi Klein, Amitav Ghosh, George Monbiot, and others. A variety of subjects naturally followed, and so the series covers everything from art and literature to economics and geopolitics, though there is a guiding concern with sustainability throughout.

In thinking about the individual selections, we again took inspiration from Thunberg’s book of speeches. In just under 80 pages, Thunberg confronted readers with a new conception of the climate crisis. She jolted us into a new understanding of whom it affects – she is of the generation we are condemning through inaction; she will be 75 years old in 2078 – and who is responsible: ‘no one is too small to make a difference’ refers to the way that ‘every single kilo’ counts when it comes to carbon emissions; none of us is exempt. These speeches are the tip of an iceberg of research – of hours spent speaking with scientists, reading scientific journals – which would be out of reach for most readers. Thunberg’s genius is the way she distils the essence of the science and thus allows millions to absorb it. We had these principles in mind when approaching the other titles in the series – we sought out accessible, representative selections of each author’s central ideas: Leopold’s ‘land ethic,’ McKibben’s ‘end of nature’, Kimmerer’s ‘principle of reciprocity’, and so on.

In thinking about the individual selections, we again took inspiration from Thunberg’s book of speeches. In just under 80 pages, Thunberg confronted readers with a new conception of the climate crisis. She jolted us into a new understanding of whom it affects – she is of the generation we are condemning through inaction; she will be 75 years old in 2078 – and who is responsible: ‘no one is too small to make a difference’ refers to the way that ‘every single kilo’ counts when it comes to carbon emissions; none of us is exempt. These speeches are the tip of an iceberg of research – of hours spent speaking with scientists, reading scientific journals – which would be out of reach for most readers. Thunberg’s genius is the way she distils the essence of the science and thus allows millions to absorb it. We had these principles in mind when approaching the other titles in the series – we sought out accessible, representative selections of each author’s central ideas: Leopold’s ‘land ethic,’ McKibben’s ‘end of nature’, Kimmerer’s ‘principle of reciprocity’, and so on.

Were there any challenges in putting together a series such as this?

Were there any challenges in putting together a series such as this?

What initially appeared to be a challenge – the logistics of co-ordinating a series remotely during a global pandemic – turned out to work to our benefit, as authors around the world have been able to connect and collaborate online as we launch the series. It has been a thrill to witness.

From the original concept to producing final copies, what ambitions do you hope to achieve with the series?

Together, the twenty short books encompass many of the key ideas in modern environmental thought. I hope that the series will be used by readers as a path through the vibrant, urgent, and perhaps occasionally overwhelming wider world of ecological writing.

With many more subjects to cover and authors to feature, are there plans to expand the series with future volumes?

Yes. Like any canon, this is an evolving ecosystem.

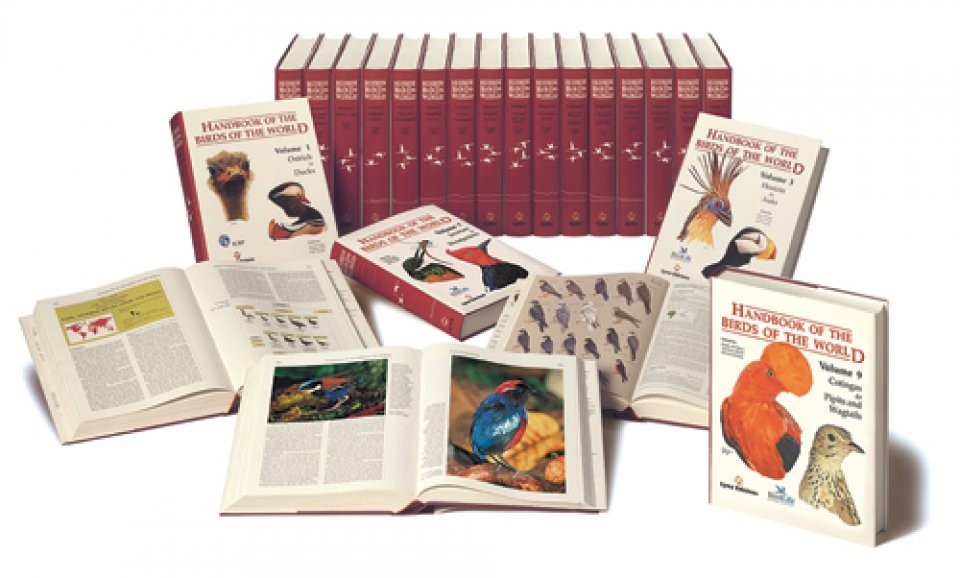

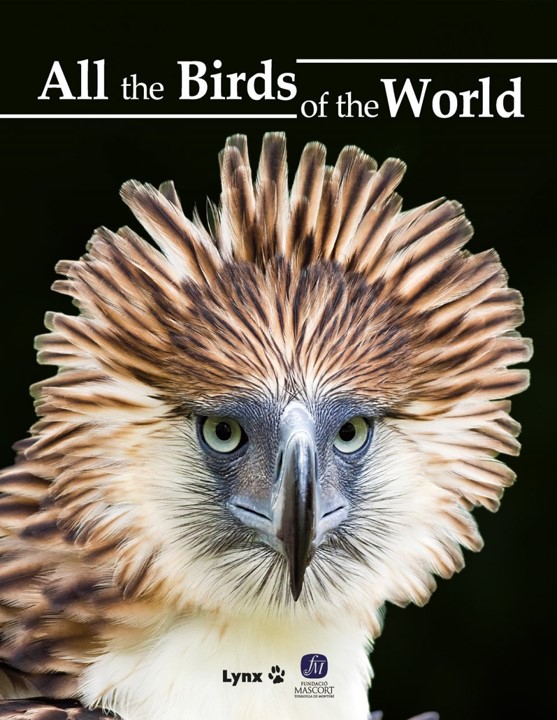

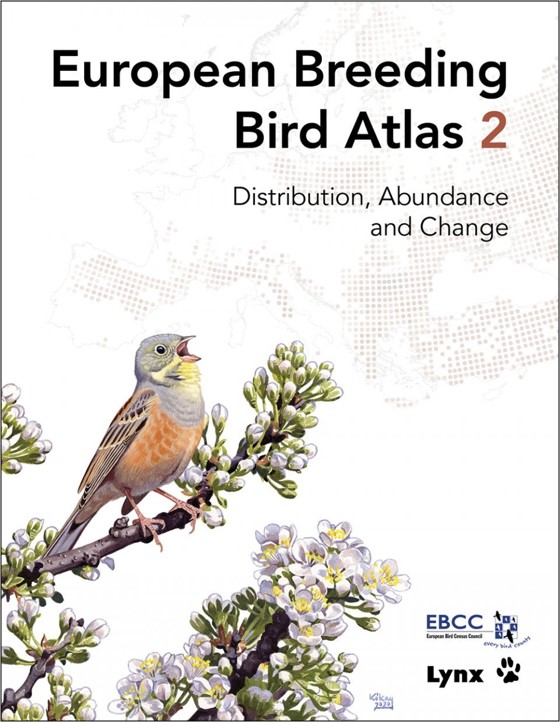

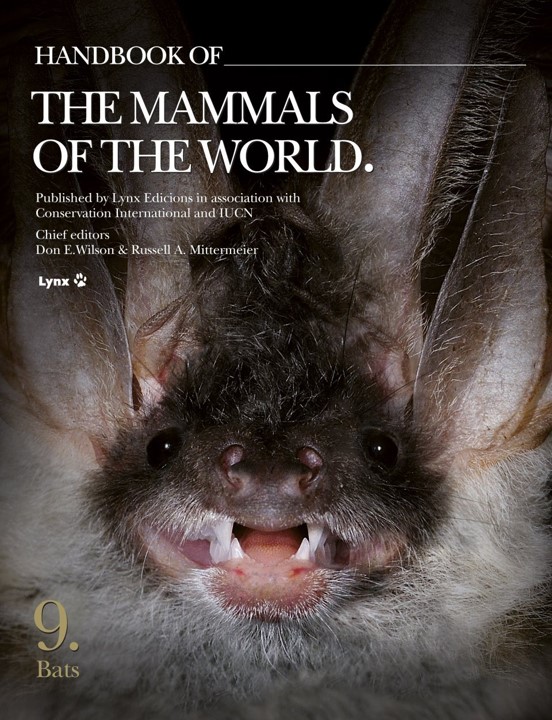

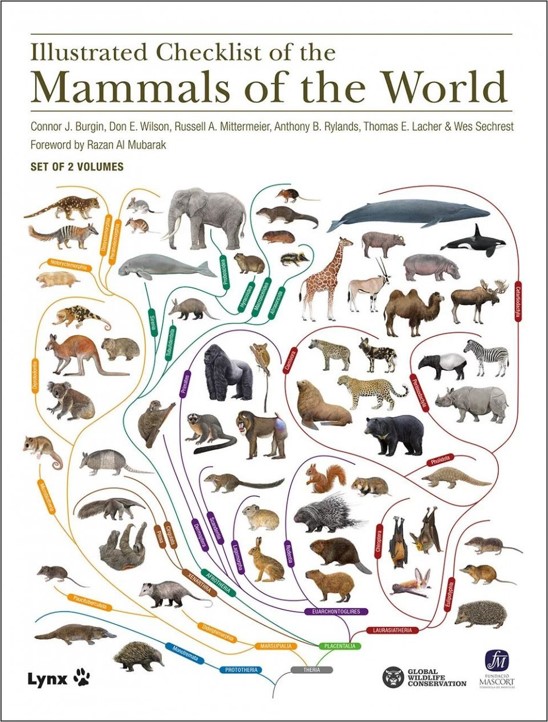

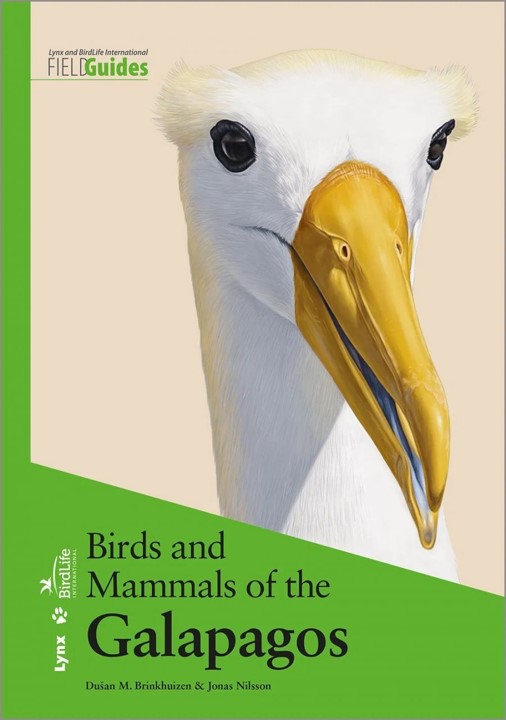

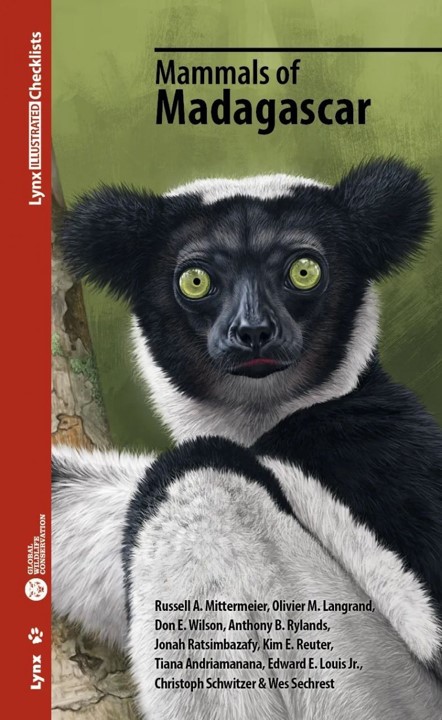

Lynx Edicions is a Barcelona-based publishing house, originally founded in 1989 to create the

Lynx Edicions is a Barcelona-based publishing house, originally founded in 1989 to create the

the line into extinction. In our Handbooks, Illustrated Checklists, Field Guides and most recently

the line into extinction. In our Handbooks, Illustrated Checklists, Field Guides and most recently

Could you tell us about how you first came to be interested in the natural world?

Could you tell us about how you first came to be interested in the natural world?

The reality is very anti-social working hours, high levels of frustration and a huge impact on home life! But I wouldn’t change it for the world as it is undoubtedly one of the most soul-nourishing jobs you could ever hope to do, in my opinion. It’s a tough, highly competitive industry, but this doesn’t mean you can’t get in through gentle persistence and dedication. Knowledge is everything: read, watch and learn everything you possibly can about your chosen wildlife subject before even attempting to film it.

The reality is very anti-social working hours, high levels of frustration and a huge impact on home life! But I wouldn’t change it for the world as it is undoubtedly one of the most soul-nourishing jobs you could ever hope to do, in my opinion. It’s a tough, highly competitive industry, but this doesn’t mean you can’t get in through gentle persistence and dedication. Knowledge is everything: read, watch and learn everything you possibly can about your chosen wildlife subject before even attempting to film it.

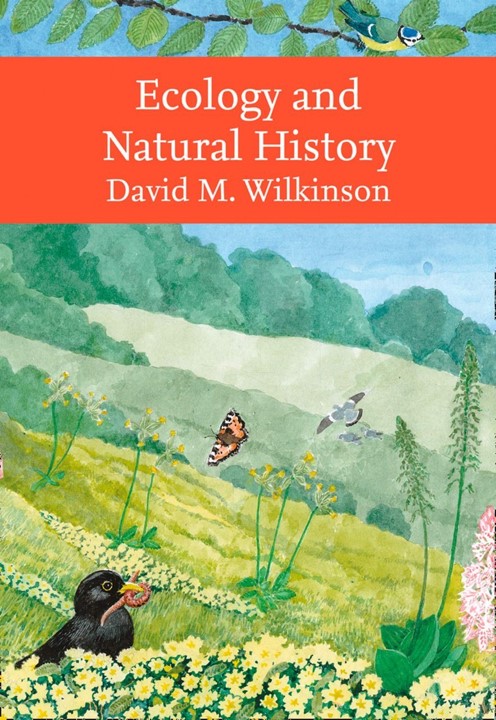

Ecology and Natural history

Ecology and Natural history

Great british marine animals

Great british marine animals

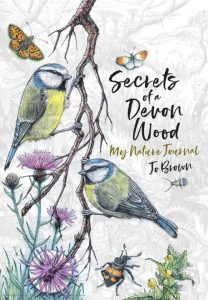

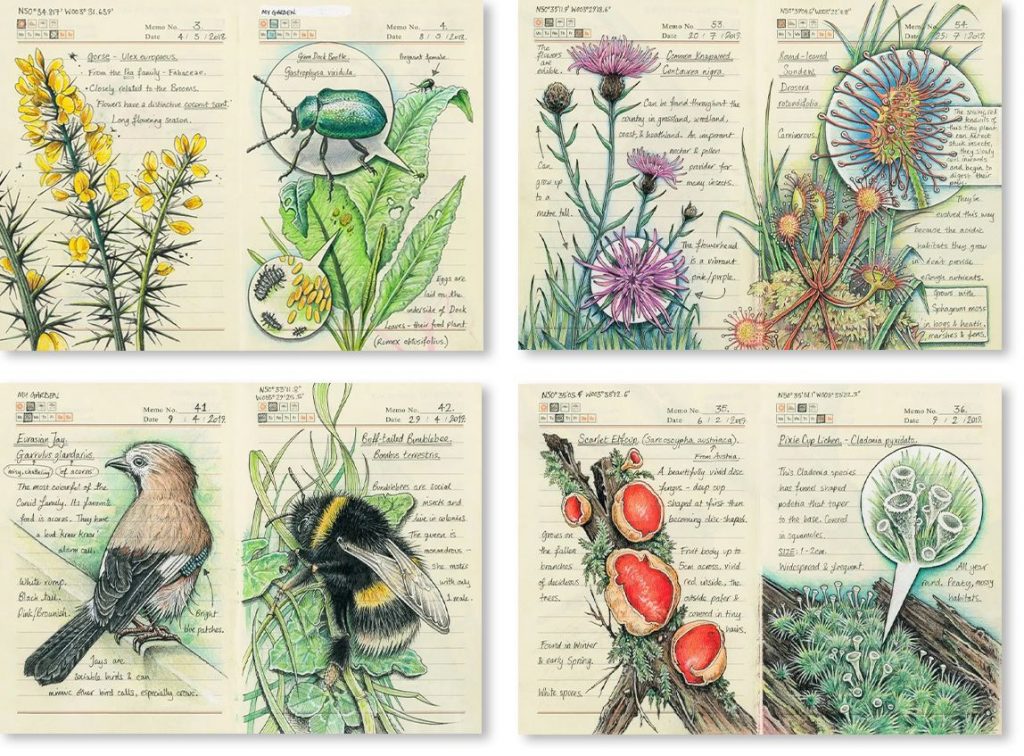

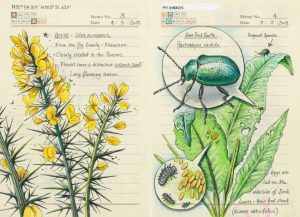

No! I wasn’t even thinking about publishing – the journal was a personal project. I realised very early on that when I draw and document things, I remember them. I remember things like Rumex Obtusifolius (the Latin name for Doc Leaf) – it’s been a wonderful learning tool and almost everything I’ve learned about nature, I’ve learned entirely on my own through observation, supported by research.

No! I wasn’t even thinking about publishing – the journal was a personal project. I realised very early on that when I draw and document things, I remember them. I remember things like Rumex Obtusifolius (the Latin name for Doc Leaf) – it’s been a wonderful learning tool and almost everything I’ve learned about nature, I’ve learned entirely on my own through observation, supported by research.

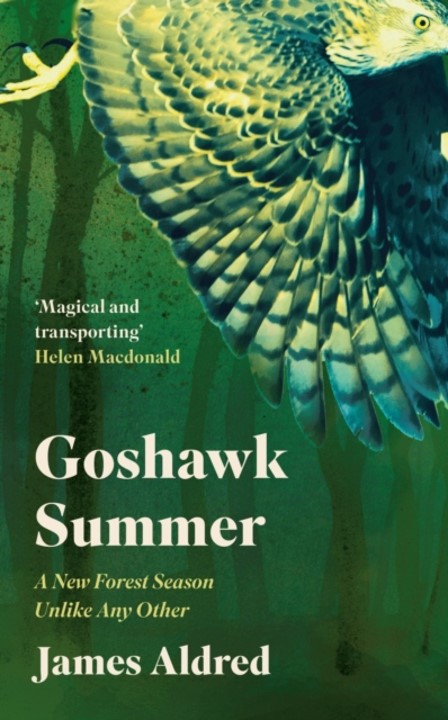

In his latest book,

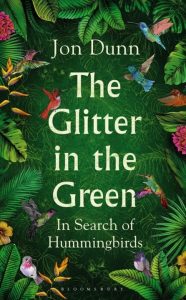

In his latest book,  shapes, forms and colours of the birds. They were so very different to the birds I was used to seeing in the Somerset countryside around our home. After that, every now and again I’d see footage of hummingbirds on wildlife documentaries, and began to appreciate further just how remarkable they were – what Tim Dee described as ‘strange birds: not quite birds or somehow more than birds, birds 2.0, perhaps’.

shapes, forms and colours of the birds. They were so very different to the birds I was used to seeing in the Somerset countryside around our home. After that, every now and again I’d see footage of hummingbirds on wildlife documentaries, and began to appreciate further just how remarkable they were – what Tim Dee described as ‘strange birds: not quite birds or somehow more than birds, birds 2.0, perhaps’. There were plenty of other moments that I’ll hold in my heart, and they don’t all involve the iconic, rare species. One such was watching Golden-tailed Sapphires, a hummingbird that looks as if it’s been dipped in rainbows, feeding in a clearing in the immediate aftermath of a heavy rain shower. As the sun broke through the dripping vegetation and steaming air we were suddenly surrounded by myriad small rainbows through which the birds were flying. That moment was ephemeral, over almost as soon as it began, but it’s etched in my memory forever.

There were plenty of other moments that I’ll hold in my heart, and they don’t all involve the iconic, rare species. One such was watching Golden-tailed Sapphires, a hummingbird that looks as if it’s been dipped in rainbows, feeding in a clearing in the immediate aftermath of a heavy rain shower. As the sun broke through the dripping vegetation and steaming air we were suddenly surrounded by myriad small rainbows through which the birds were flying. That moment was ephemeral, over almost as soon as it began, but it’s etched in my memory forever.  I found myself asking myself that very question as my journey into their world unfolded… Hummingbirds certainly seem to touch something deep inside us. They featured in the mythology of the Aztecs; inspired the most dramatic of all of the immense geoglyphs carved into the desert floor by the Nazca; appear in renowned art and literature; and, to this day, are singled out for particular love by those whose gardens they frequent, people who would not necessarily identify themselves as birders.

I found myself asking myself that very question as my journey into their world unfolded… Hummingbirds certainly seem to touch something deep inside us. They featured in the mythology of the Aztecs; inspired the most dramatic of all of the immense geoglyphs carved into the desert floor by the Nazca; appear in renowned art and literature; and, to this day, are singled out for particular love by those whose gardens they frequent, people who would not necessarily identify themselves as birders. Inevitably there were some logistical challenges to contend with, not least having to reacquaint myself with horse-riding after a decades-long and deliberate avoidance of it! There were a couple of close encounters with large predators that were, in hindsight, more alarming than they felt at the time – as a naturalist, I was thrilled to get (very) close views of a puma… But perhaps the most challenging moment of all was landing in Bolivia at the very moment the country was taking to the streets to protest the outcome of a recent presidential election. There was an incident at a roadblock manned by armed men that was genuinely scary, with an outcome that hung in the balance for a terrifying instant, and could easily have ended badly.

Inevitably there were some logistical challenges to contend with, not least having to reacquaint myself with horse-riding after a decades-long and deliberate avoidance of it! There were a couple of close encounters with large predators that were, in hindsight, more alarming than they felt at the time – as a naturalist, I was thrilled to get (very) close views of a puma… But perhaps the most challenging moment of all was landing in Bolivia at the very moment the country was taking to the streets to protest the outcome of a recent presidential election. There was an incident at a roadblock manned by armed men that was genuinely scary, with an outcome that hung in the balance for a terrifying instant, and could easily have ended badly. I sometimes think there’s almost too much optimism expressed when talking about conservation challenges anywhere in the world – a narrative that suggests “if we only care enough, the [insert iconic species name here] can be saved”. And to a degree, that’s good – we’ve got to have hope, as the alternative is too dreadful to countenance – but given our impact to date, and in an uncertain future where the effects of climate change are still unfolding and will continue for many decades to come, to name just the biggest of the mounting pressures on the natural world, I’m not sure that I do feel terribly optimistic, least of all for those hummingbird species that have very localized populations, or depend upon very specific habitats. They’re undeniably vulnerable. But like Fox Mulder,

I sometimes think there’s almost too much optimism expressed when talking about conservation challenges anywhere in the world – a narrative that suggests “if we only care enough, the [insert iconic species name here] can be saved”. And to a degree, that’s good – we’ve got to have hope, as the alternative is too dreadful to countenance – but given our impact to date, and in an uncertain future where the effects of climate change are still unfolding and will continue for many decades to come, to name just the biggest of the mounting pressures on the natural world, I’m not sure that I do feel terribly optimistic, least of all for those hummingbird species that have very localized populations, or depend upon very specific habitats. They’re undeniably vulnerable. But like Fox Mulder,

and usually open 24 hours – but there is no reason why we can’t include habitats for our wildlife. A simple solution would be to leave areas un-mowed to grow wild. In the parks of my local area in London, large swathes of grasses and flowers have been left to mature and people have been really receptive to it. I think we are finally moving away from the Victorian ideal of neat and tidy!

and usually open 24 hours – but there is no reason why we can’t include habitats for our wildlife. A simple solution would be to leave areas un-mowed to grow wild. In the parks of my local area in London, large swathes of grasses and flowers have been left to mature and people have been really receptive to it. I think we are finally moving away from the Victorian ideal of neat and tidy!

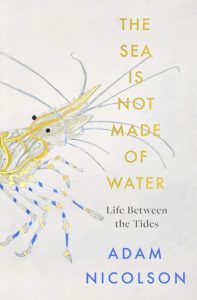

For nearly thirty years now I have been going to stay in a small house at the head of a bay on the west coast of Scotland. It is somewhere my wife’s family have been going for generations and now our children and grandchildren love it too. It has everything you might long for from a place like that: cliffs, woods, waterfalls, a dark beach made of basalt sands, a lighthouse, a ruined castle, stories, beauty, birds, fish; but one thing it did not have because of the geology, was a rockpool. For years I have dreamed of making one – a place of stillness set in the tide, and this book is the story of how I made three of them in different parts of the bay; one dug in with a pickaxe; one made by damming a narrow exit to the sea from a hollow so that the dam held the pool behind it; and one by making a circular wall low down in the intertidal.

For nearly thirty years now I have been going to stay in a small house at the head of a bay on the west coast of Scotland. It is somewhere my wife’s family have been going for generations and now our children and grandchildren love it too. It has everything you might long for from a place like that: cliffs, woods, waterfalls, a dark beach made of basalt sands, a lighthouse, a ruined castle, stories, beauty, birds, fish; but one thing it did not have because of the geology, was a rockpool. For years I have dreamed of making one – a place of stillness set in the tide, and this book is the story of how I made three of them in different parts of the bay; one dug in with a pickaxe; one made by damming a narrow exit to the sea from a hollow so that the dam held the pool behind it; and one by making a circular wall low down in the intertidal.

And so that provided the model – see what was there and look carefully at it. Of course, books like mine are entirely parasitic on the work of many generations of biologists and that too turned out to be the pattern. Watch the sand hoppers and then read about them. Read about them and see how much of what I read I could find on the shore. With prawns, winkles, shore crabs, anemones, limpets, sea-stars, urchins and barnacles, I simply oscillated between the pools and my books: what was there? What had people discovered about them? How did they interact? What were the principles governing their presence or absence? And with all of that came the repeated and slightly sobering realisation that unless I knew to look for something it was very difficult to see it was there. Mysteriously, we are often blind to what is in front of our eyes.

And so that provided the model – see what was there and look carefully at it. Of course, books like mine are entirely parasitic on the work of many generations of biologists and that too turned out to be the pattern. Watch the sand hoppers and then read about them. Read about them and see how much of what I read I could find on the shore. With prawns, winkles, shore crabs, anemones, limpets, sea-stars, urchins and barnacles, I simply oscillated between the pools and my books: what was there? What had people discovered about them? How did they interact? What were the principles governing their presence or absence? And with all of that came the repeated and slightly sobering realisation that unless I knew to look for something it was very difficult to see it was there. Mysteriously, we are often blind to what is in front of our eyes. stages, can recognise the movements and timings of the tides. That sea anemones can identify other sea anemones that are not their relations and effectively destroy them. That prawns have an imagination – that might sound like too much, but it has been shown that they can remember past pain and project it into present and future anxieties. Anxiety is different from fear; it is a fear of what might be there. In other words a prawn can think beyond its present reality.

stages, can recognise the movements and timings of the tides. That sea anemones can identify other sea anemones that are not their relations and effectively destroy them. That prawns have an imagination – that might sound like too much, but it has been shown that they can remember past pain and project it into present and future anxieties. Anxiety is different from fear; it is a fear of what might be there. In other words a prawn can think beyond its present reality. garden whose walls are dissolved twice a day, an enclosure that becomes part of the general world with every high tide. That ambiguity is what entranced me, the sense of its being a micro-ocean, a micro-arcadia, a micro-laboratory in which all kinds of intimacies and precision in natural beings can be witnessed an inch beneath your nose.

garden whose walls are dissolved twice a day, an enclosure that becomes part of the general world with every high tide. That ambiguity is what entranced me, the sense of its being a micro-ocean, a micro-arcadia, a micro-laboratory in which all kinds of intimacies and precision in natural beings can be witnessed an inch beneath your nose.

slow I would be overtaken by very old people on Zimmer frames. It seemed as though I’d hit 97 five decades prematurely.

slow I would be overtaken by very old people on Zimmer frames. It seemed as though I’d hit 97 five decades prematurely.