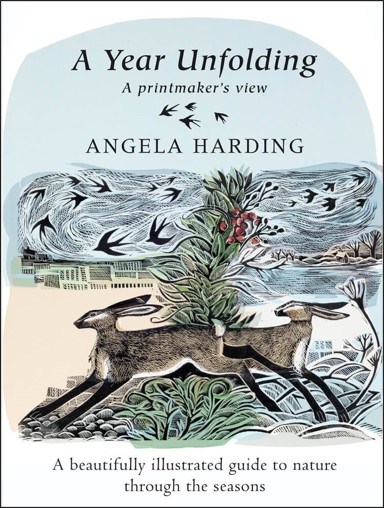

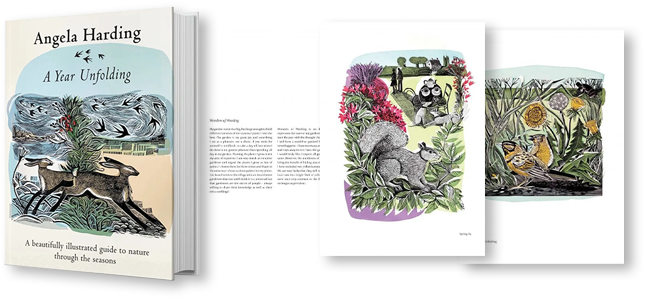

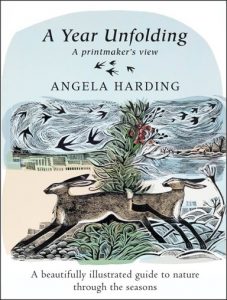

A Year Unfolding: A Beautifully Illustrated Guide to Nature Through the Seasons is a stunning book by much-loved printmaker Angela Harding, the first solely dedicated to her art. It is a celebration of Angela’s beautiful prints and a glimpse into her detailed and meticulous process.

A Year Unfolding: A Beautifully Illustrated Guide to Nature Through the Seasons is a stunning book by much-loved printmaker Angela Harding, the first solely dedicated to her art. It is a celebration of Angela’s beautiful prints and a glimpse into her detailed and meticulous process.

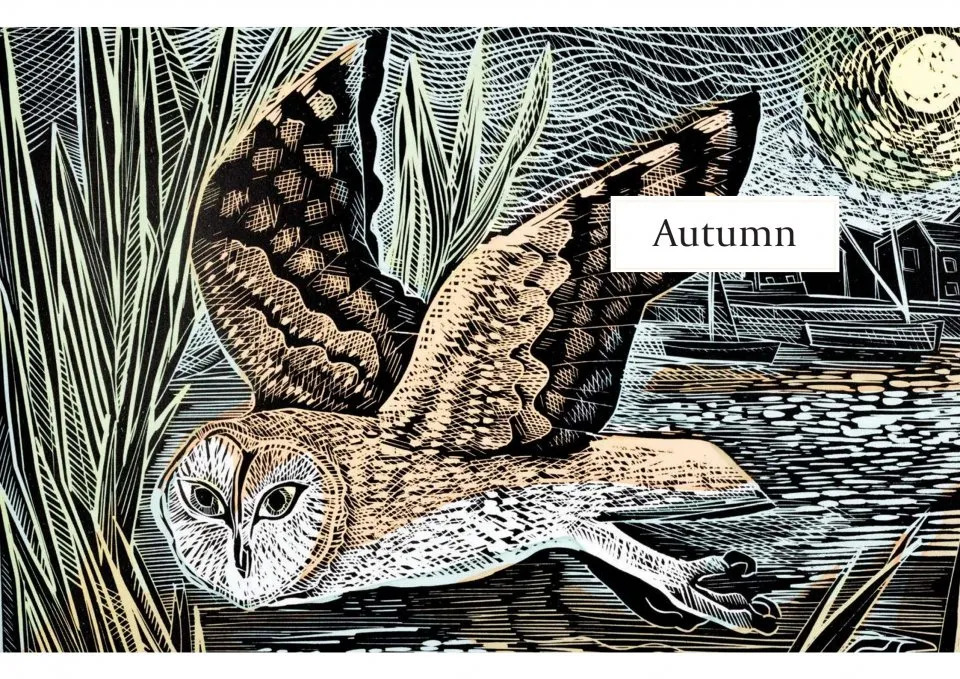

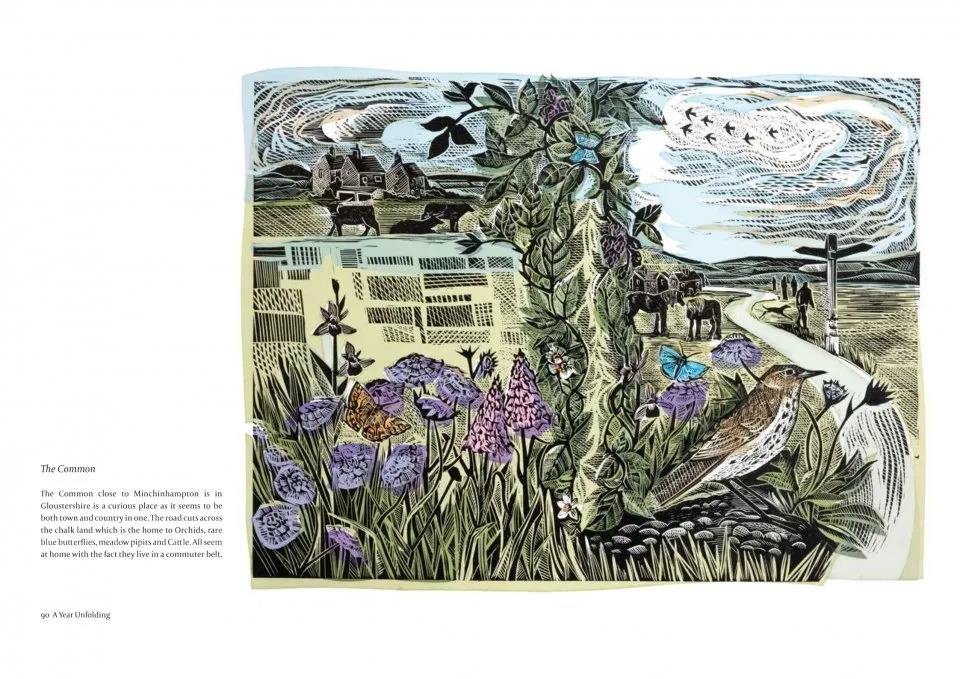

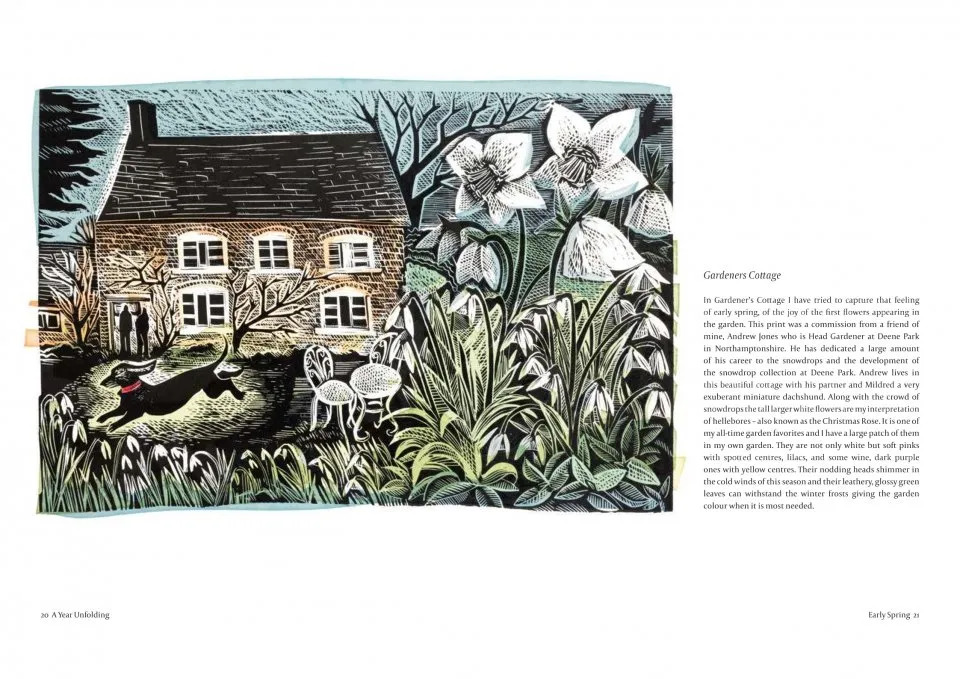

A Year Unfolding is a journey through Angela’s year in nature, watching the seasons unfold in front of her studio in Rutland. This book shows how nature transforms and evolves over the course of the year, while also telling the stories behind some of Angela’s most popular images, giving context to her celebrated works, as well as new art created specifically for the book. The beautiful illustrations and evocative imagery of the prose make this the perfect book for readers and art lovers everywhere.

Angela Harding has kindly taken the time to answer a few questions for us below.

Could you tell us how you became interested in nature and printmaking?

Born in Stoke-on-Trent, the Potteries, one of the most industrial parts of the UK, it is perhaps surprising that I am more at home in the countryside than in towns. At school, I was the misfit teenager in socks rather than tights, whose bedroom was plastered with bird posters rather than popstars. So it has continued into my adult life, I have never lost my love of the natural world and in particular, birds still inspire my work. As a student of Fine Art at Leicester Polytechnic in the 1980s, I was first introduced to printmaking. My student home was a tiny cottage in the graveyard of St Marys church in Melton Mowbray. I would cycle the 18 miles to Leicester, collecting roadkill that I strapped to my handbags to draw at college. These drawings would then be turned into prints; at that time, I mainly worked in drypoint and etching. So my love of drawing moved easily into a love of printmaking. Today I work in a combination of block printing and silkscreen, but you can still see my love of line in the way I carve the blocks I make.

A Year Unfolding is a journey through the seasons. Why did you decide to give early spring and early summer their own chapters?

I love all the British seasons, but of all of them, it is the energy of spring and early summer that inspires many of my images. I always try to bring movement into my work, so there is a natural fit with the bursts of new growth and new life you get at these times of year. Also, the intensity of colour, the fresh greens of the garden and hedgerow. Birds become so much part of our day in spring and early summer, in the beauty of their songs and in their mad dashing flight to build nests and find mates.

The natural world takes centre stage in your prints; how important do you think art is in bringing awareness to the environment and how do you think it could be better used?

All of us have moved so far from a proper connection with the natural world—our comforts come high on what we need or what we think we need. So if my prints are a small reminder of the fact that we are very much part of the natural world, I am honoured. We all cherish those moments when we spot a kingfisher or come across a hedgehog in the garden. I hope, in my work, I communicate some of that joy. So if these wonders of experience with nature are to continue and grow, we need to be reminded how special they are and how much we value them.

You’ve created many beautiful and striking book covers, including English Pastoral, The Wild Isles and The Salt Path. What is the process of creating these? Do you approach each project differently?

You’ve created many beautiful and striking book covers, including English Pastoral, The Wild Isles and The Salt Path. What is the process of creating these? Do you approach each project differently?

Working with publishers over the years has given me wonderful opportunities to create new work and see my work published on a variety of themes. The advantage of being an older illustrator is that I come with a lifetime of experience. So when I was asked to do the cover for Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path, I could draw on the experience of having walked that coast path and spent a lot of my youth camping in Cornwall. I hope it is evident in the illustration I made for The Salt Path how much I love Cornwall and what great times I have had exploring its coastline.

The covers English Pastoral and The Wild Isles both used print that I had already made and luckily fitted with the themes of the books. English Pastoral featured a print call the Shippen Curlew—made after visiting my friends Mary and Hugh Elliot, who run the Twenty Twenty Gallery in Ludlow. Shippen is the Shropshire word for sheep shed and they live in a converted Shippen surrounded by farmland. Very sadly, Shropshire curlews are not as common as they were when I lived in Shropshire in my 20s, but they are still a bird I very much associate with the area. The Wild Isles shows a nightjar and moth against a seascape—this image is one of three prints made on the same theme. It was inspired by the trips my husband and I make on our small wooden boat—a lot of our summer months are spent sailing on the east coast of Britain.

What prompted you to make the jump from illustrator to author and create your own book?

I have always wanted to collect my work into a book. I work in themes and series so even though many of the images were made years apart, they fit together well. I hope the writing in the book is ok; I am, of course, more comfortable with a pen or chisel! I do come from a literary background; my father was an unpublished poet and a great influence. He studied English at Cambridge in the late 1940s under Professor F. R. Leavis. It is a shame my father is no longer here to see my book; I hope he would have approved. The poems that mark my chapter headings are ones we often shared together.

Finally, do you have any further projects planned that you’d like to tell us about?

I do have new projects in mind, but nothing definite that I can share with you at the moment. I am hoping to do a series of prints about the British coast that my husband and I visit on Wingsong, our boat. Travelling by boat and bike gives a different perspective on our landscape—we mainly spend time on the east coast moving from Suffolk up to Shetland, but we have both been around the whole coast by boat and by bike.