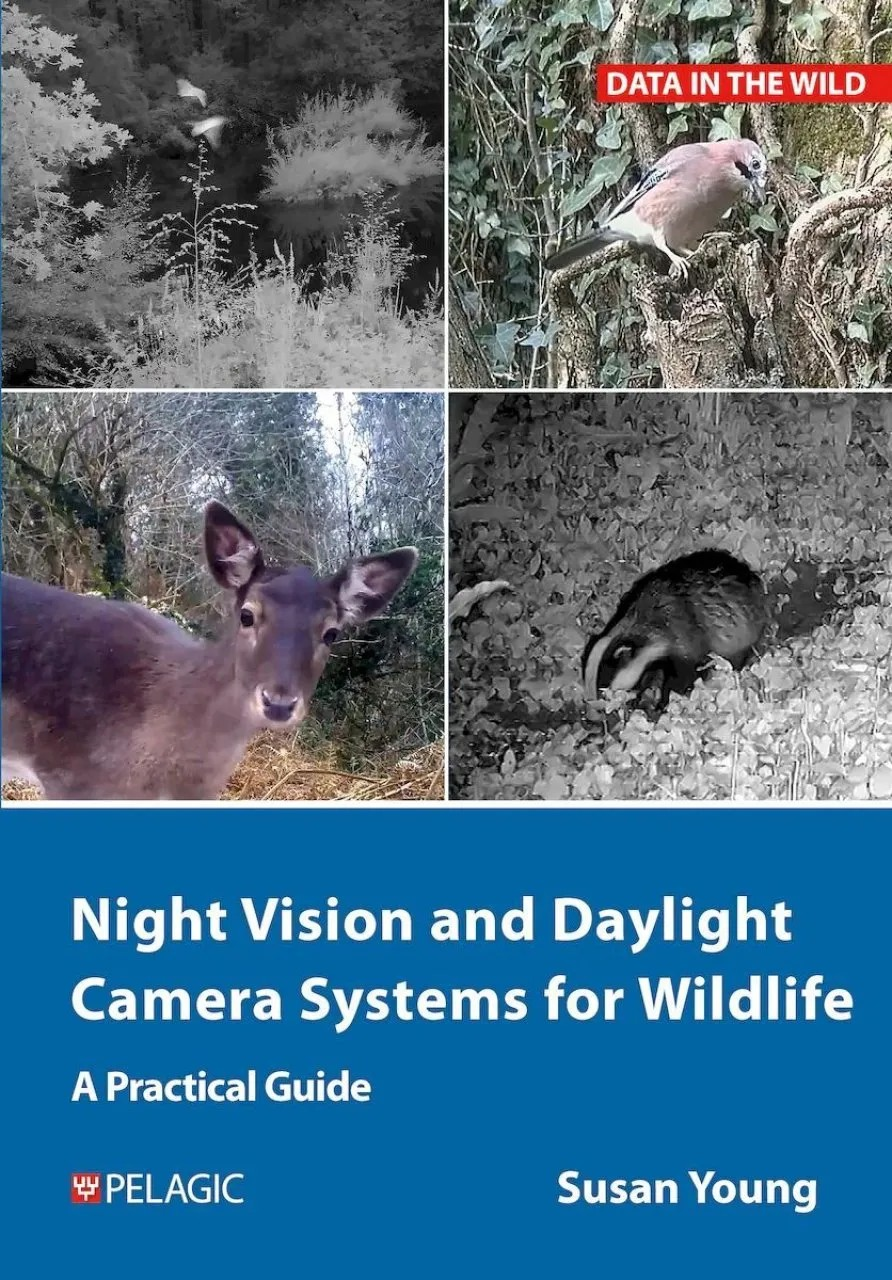

This comprehensive guide describes how wildlife can be monitored and recorded in a non-intrusive way using well-developed and reliable technology. Detailing key techniques for capturing high-quality footage of a range of species, from nocturnal mammals to elusive birds, this practical resource is ideal for both professional ecologists and amateur naturalists alike who are seeking to enhance their understanding of the natural world.

This comprehensive guide describes how wildlife can be monitored and recorded in a non-intrusive way using well-developed and reliable technology. Detailing key techniques for capturing high-quality footage of a range of species, from nocturnal mammals to elusive birds, this practical resource is ideal for both professional ecologists and amateur naturalists alike who are seeking to enhance their understanding of the natural world.

Susan Young is a photographer and writer based in South Devon, who has a wealth of experience in wildlife photography. She has authored several books, including CCTV for Wildlife Monitoring and Wildlife Photography Fieldcraft, and is currently carrying out research with Natural England, the Woodland Trust and Mammal Society on the use of remote cameras for wildlife monitoring.

Susan Young is a photographer and writer based in South Devon, who has a wealth of experience in wildlife photography. She has authored several books, including CCTV for Wildlife Monitoring and Wildlife Photography Fieldcraft, and is currently carrying out research with Natural England, the Woodland Trust and Mammal Society on the use of remote cameras for wildlife monitoring.

We recently spoke to Susan about her latest book, where she explained how she first started working with visual systems, how ecological and wildlife-watching camera systems differentiate, and more.

Firstly, could you share a little bit about yourself and your background working with visual systems?

My background is in physics and engineering, but I have had a keen interest in wildlife from a very early age. Since moving to Devon some years ago, I developed my interest in photography and wrote several books on various technical topics. I used trail cameras before they became ‘famous’ and finding some aspects frustrating, moved to bird box cameras – I then became interested in using security cameras with separate recorders as they had more useful features.

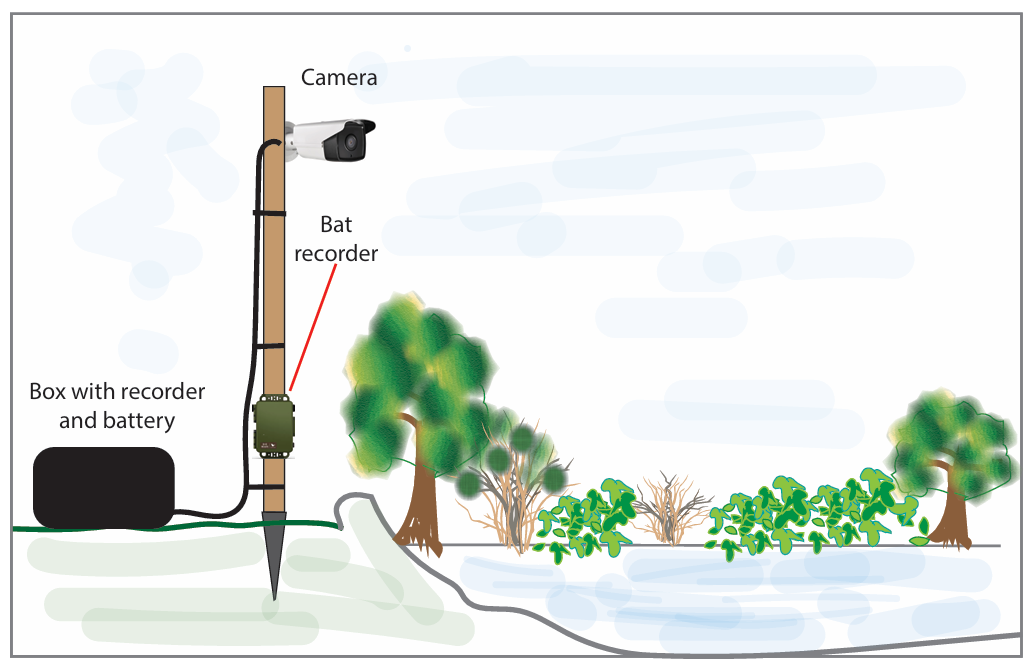

In 2015/2016 I started as a volunteer with Natural England and the Woodland Trust where I was encouraged to develop my ideas for portable CCTV systems, which led to the discovery of three calls of Barbastelle Bats not previously recognised. Further work with dormice, otters, deer, small mammals and birds showed just how well the systems performed, being much richer in features than trail cameras and much less expensive than thermal systems.

Your previous book, CCTV for Wildlife Monitoring was published in 2016. What inspired you to revisit the topic for a second book, and what advancements or changes does your latest title encompass?

My book in 2016 was more of an introduction to CCTV technology, which was just taking off and becoming more readily available. Since then, the technology has advanced dramatically, with HD cameras giving very high-quality images, and recorders becoming available with solid state drives making them very portable.

There are many other features not found in other visual systems – in particular, security recorders have inbuilt video analysis which can be controlled by the user, greatly reducing the amount of video data to analyse. My book has detailed step-by-step instructions for all aspects of the night vision camera systems with the aim of flattening the learning curve.

Night Vision systems are commonly associated with ecological research and wildlife watching, how do the camera systems you describe differentiate from them?

The systems I describe have a raft of features, as described above, making analysis much easier. They can also be left outside unattended and are particularly useful for remote areas. They are also relatively low cost and portable.

Why did you feel that it was important to include a section on public engagement and education in this book?

Public engagement is important for raising awareness of the plight of our wildlife, as well as for attracting funding. High-quality videos from security camera systems, particularly of protected or rarely seen species, have proven successful. My book gives step-by-step instructions to encourage the use of this technology without the need for costly specialists.

Regarding schools, introducing children to technology at an early age makes use of the systems less daunting in later life.

Have you come across any emerging or under-utilised applications for this technology that you believe hold potential?

Many of the applications I have developed using my camera systems are new and I believe hold great potential. Because the systems can be set up and left for long periods, it means little or no disturbance to wildlife – for example monitoring breeding birds of prey in remote habitats, observing dormice behaviour in dormouse boxes, or surveying bats in hazardous environments.

Have you encountered any particularly memorable or exciting wildlife captures? Can you share any highlights from your experience?

On the conservation front, discovering new Barbastelle calls was very exciting, as was viewing previously unseen dormouse behaviour. On the naturalist level, filming four young Fallow Deer running round and round my rural garden in play was very heart-warming.

Finally, what’s next for you?

I am planning some research using my systems for small mammals which are often under-recorded. I am also producing educational material for the Mammal Society.

Night Vision and Daylight Camera Systems for Wildlife is available here.