Mosses belong to a group of plants called bryophytes. Comprising the mosses, liverworts and hornworts, there are over 1000 species of bryophyte in Britain and Ireland, which is around 58% of the species found in the whole of Europe.

Although often overlooked, mosses are fascinating to study and are structurally both complex and elegant. When seen through a hand lens or microscope they have details that easily compare in beauty with those of their larger plant cousins.

In this article we’ll introduce you to a handful of some of the commonest and easiest to identify mosses that you will find in the UK. If you’re interested in learning more, we’ve also provided a list of excellent field guides and books at the bottom of the guide, along with some helpful links to other online resources.

Why are mosses important?

Mosses are one of the first plants to colonise bare ground. They provide important habitat for invertebrates, particularly those fond of a damp environment such as slugs and woodlice. A healthy mossy environment will also be attractive to larger animals who feed on these invertebrates, such as frogs and toads, and will provide shelter to a diverse range of microscopic organisms, including nemotodes, rotifers and tardigrades.

Mosses can hold a huge amount of water and so play a crucial role in mitigating flooding during periods of intense rainfall. Sphagnum moss in particular can absorb up to 20 times its weight in water, and is instrumental in slowing the flow of rainwater from the hills and moors and reducing the risk of flooding in downstream towns and cities.

Did you know?

- Mosses have stems and leaves but no true roots or advanced vascular systems. This is why we only have small mosses and not ones that are the size of trees!

- There are around 20,000 species of moss worldwide and they are found everywhere except for in the sea – even in Antarctica!

- Unlike flowering plants, mosses produce spores rather than seeds and flowers. Spores are produced in a small capsule which grows on a long stem called a seta.

- Mosses require damp conditions for reproduction – this is because the male cells require a film of water in order to reach the female cells and fertilise them.

Common UK mosses

Rough-stalked feather moss (Brachythecium rutabulum)

Also known as ‘ordinary moss’, rough-stalked feather moss is one of our most common moss species, and can be found growing widely in woodlands, lawns and at the base of hedges. It is yellow-green in colour and has branching stems with pointed oval leaves. Shoot tips are generally pale and glossy. Curved, egg-shaped capsules are frequently produced.

Common haircap (Polytrichum commune)

Also known as marsh hair moss, common haircap is one of our tallest species of moss and can form clumps up to 40cm in height. Found in damp, acidic areas such as heaths, bogs and moorland, it can also be found near to streams and rivers within woodland. Plants are bright green, fading to brown with age, and often grow in compact clumps. The stems are tough and wiry, and its leaves are narrow and spear-shaped. When viewed from above, each individual stem looks star-like. In the summer it produces brown, box-shaped capsules.

Swan’s-neck thyme-moss (Mnium hornum)

Swan’s-neck thyme-moss is abundant in acidic woodland on logs, rocks and soil. It has upright stems which are 2–4cm tall, and leaves which are approximately 4mm in length with a toothed border. Frequently produces capsules on the end of 2.5–5cm long stalks. Capsules have a pointed tip.

Common tamarisk moss (Thuidium tamariscinum)

Common tamarisk moss is very distinctive and forms loose mats of fern-like shoots which range from yellow-green to dark green. Individual leaves are triangular or heart shaped, and the stems can be green or red-brown. It forms capsules only occasionally in the autumn and winter. It commonly grows on neutral soil in woodland, hedges and damp grass.

Sphagnum moss (Sphagnum spp.)

There are more than 30 species of sphagnum moss in the UK and they can be very difficult to tell apart. Although each plant is small, they often grow together in dense mats to form large areas of spongy carpet. Sometimes referred to as ‘bog-mosses’, they can be beautifully multi-coloured and thrive on peat bogs, marshland, heath and moorland. They also have an important role in the formation of peat bogs.

Common striated feather-moss (Eurhynchium striatum)

Common striated feather-moss is common in lowland woodland, particularly those with a high clay soil. It often forms cushions or mats that can cover large areas. Leaves are triangular or heart-shaped with finely toothed margins and have wrinkles that run down the length of the leaf (you may need a hand lens to observe this identifying feature). Spore capsules are only occasionally present, but have a beak-shaped tip.

Recommended reading

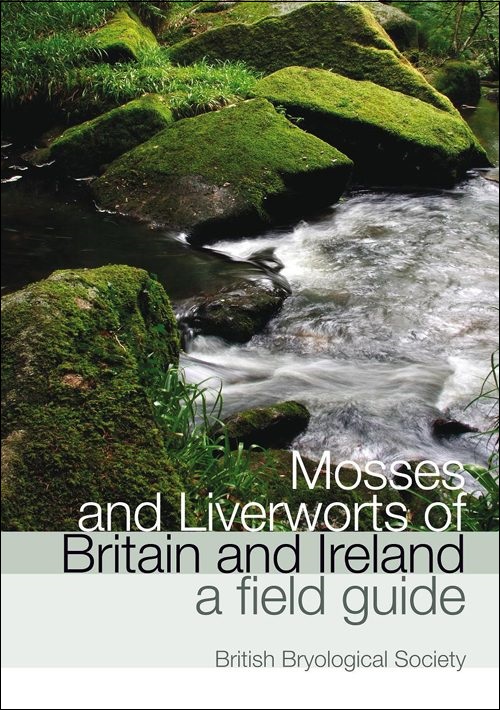

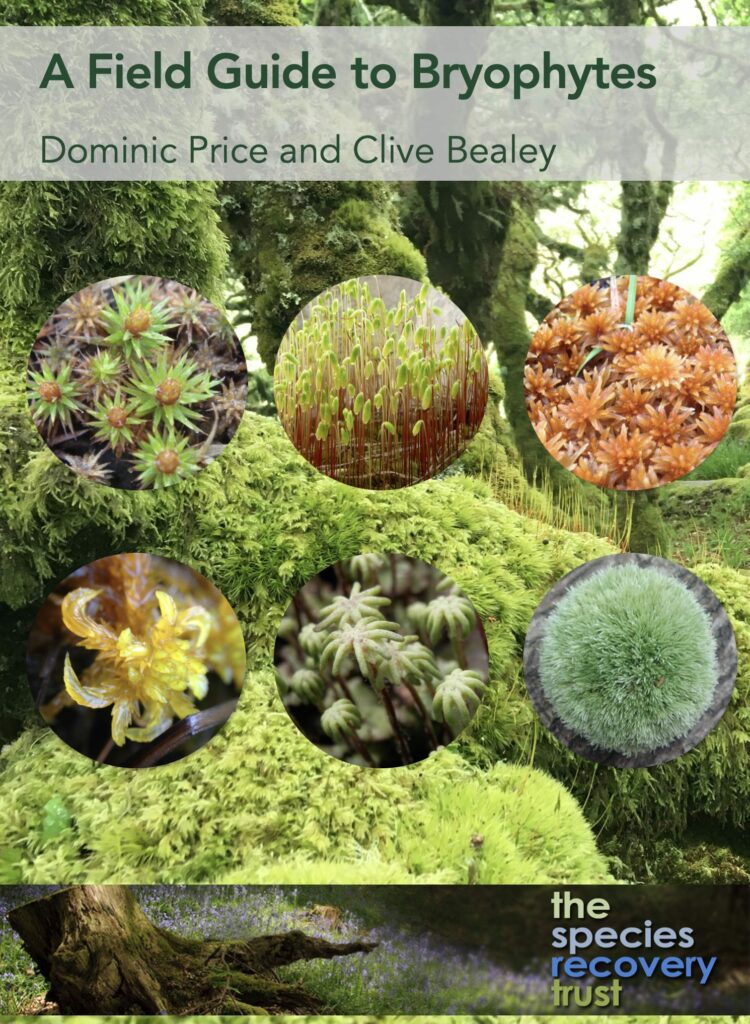

This field guide covers 133 species of moss and liverwort encountered in most UK habitats, using non-specialist terms to help identify them on over 100 full-colour pages. Twelve flow-charts help identify species by the habitat they occur in. All proceeds from the sale of this book go directly to the conservation program of The Species Recovery Trust.

Mosses and Liverworts of Britain and Ireland: A Field Guide

Mosses and Liverworts of Britain and Ireland: A Field Guide

This invaluable guide features hundreds of colour photographs and black and white drawings, both of whole plants and with distinguishing features magnified. It also includes notes on how to identify and distinguish plants from similar species, alongside distribution maps and habitat notes.

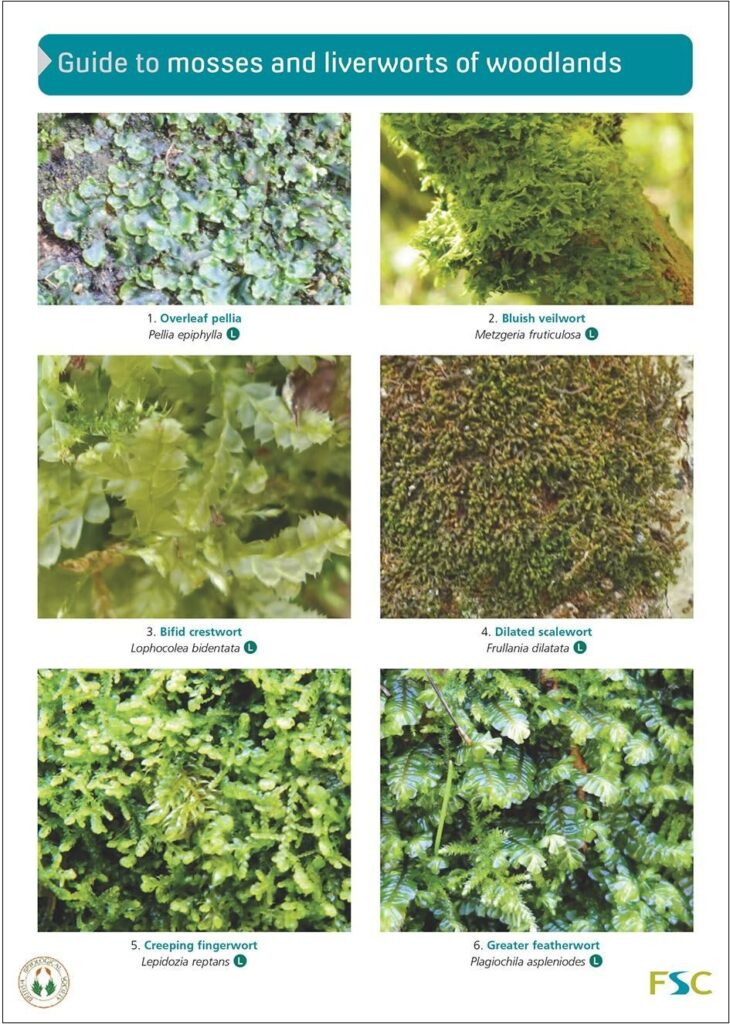

Guide to Mosses and Liverworts of Woodlands

Guide to Mosses and Liverworts of Woodlands

Mosses and liverworts can form quite an extensive part of the woodland flora, carpeting the ground and covering tree trunks and branches. This guide covers seven liverworts and 16 mosses commonly found in woodlands. Photographs of plants in the wild and brief identification notes are provided to aid identification.

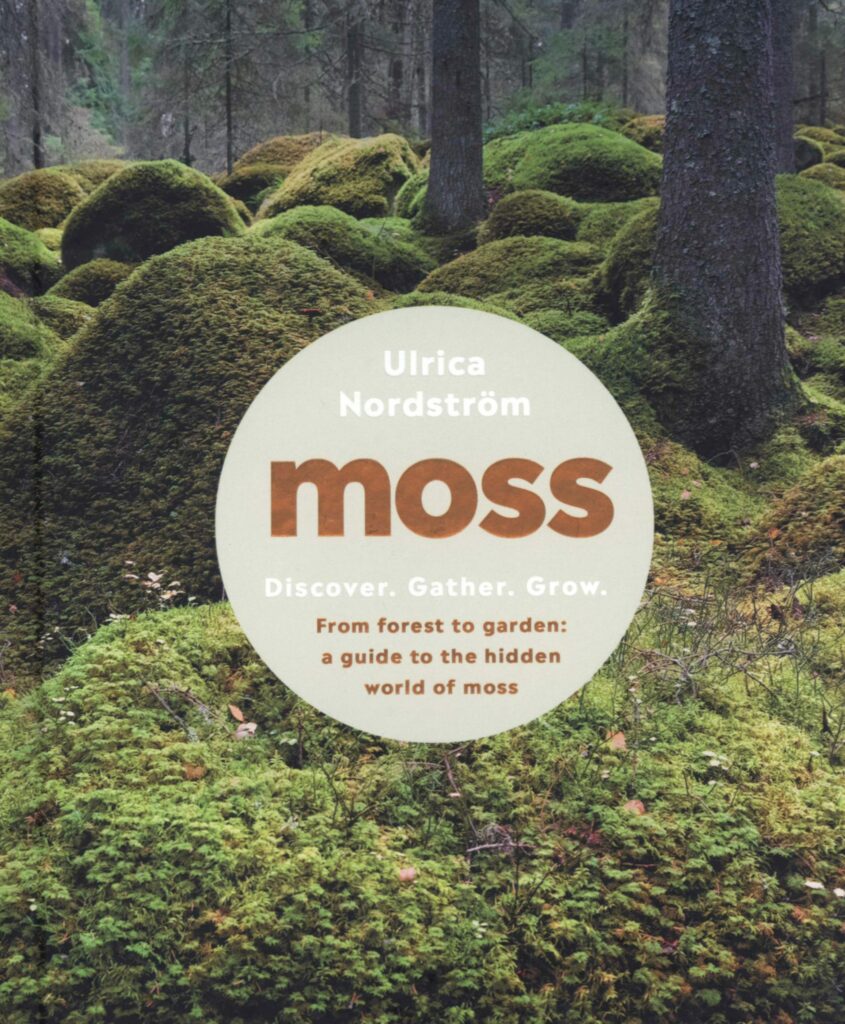

Moss: From Forest to Garden: A Guide to the Hidden World of Moss

In Moss you’ll discover the key moss varieties and where they can be found, as well as the cultural history of moss both as a garden plant and its uses in traditional handicrafts. Take a tour of the best moss gardens in Japan, the UK and the US, and meet people who share their passion for these plants.

Useful links

British Bryological Society (BBS) – The BBS supports anyone interested in the study and conservation of mosses, from the absolute beginner to the experienced researcher. They host field meetings, organise recording and research projects, and publish an academic journal as well as a popular membership magazine.

Mosses and Liverworts of Town and Garden (pdf) – This downloadable leaflet will help you to identify some of the most common species of moss and liverwort with the use of a hand lens.

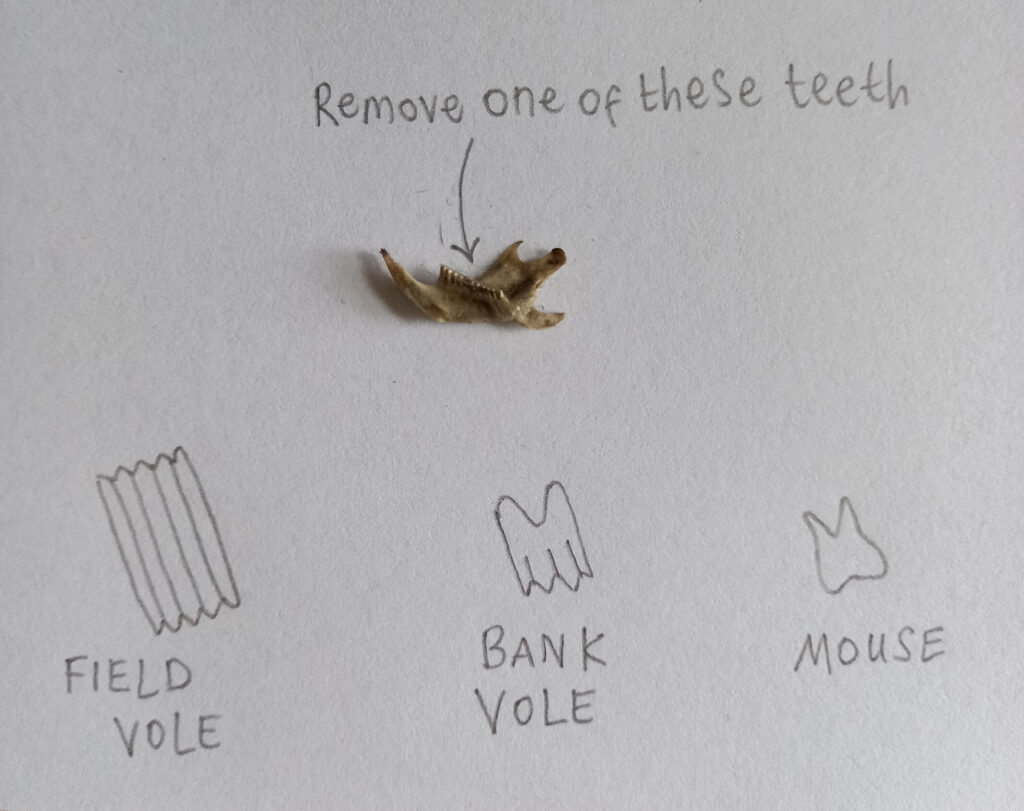

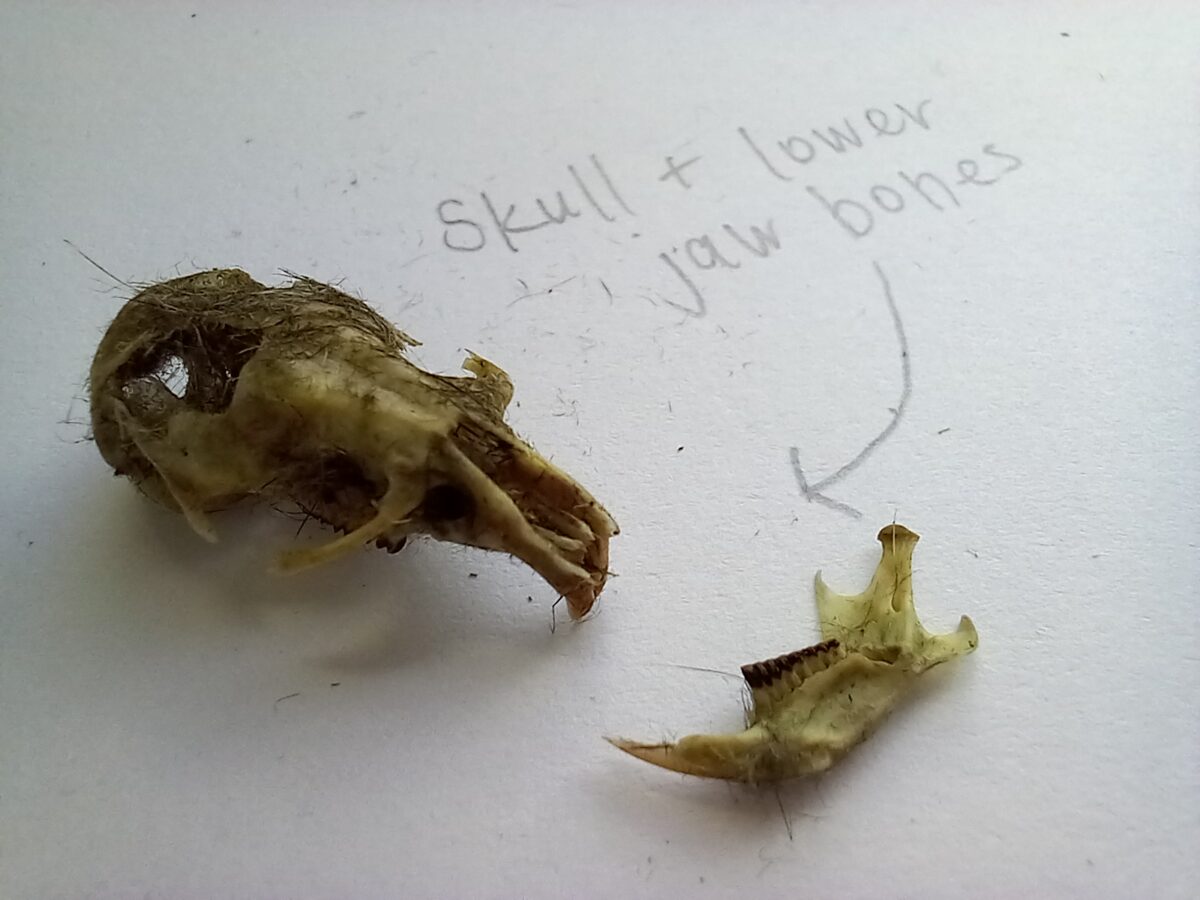

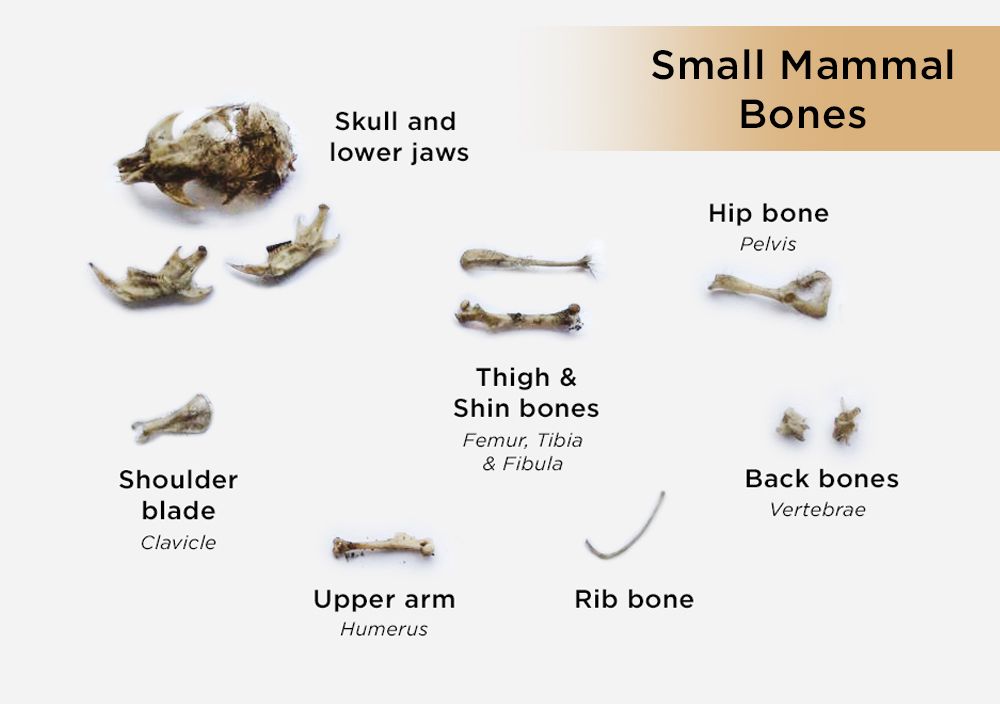

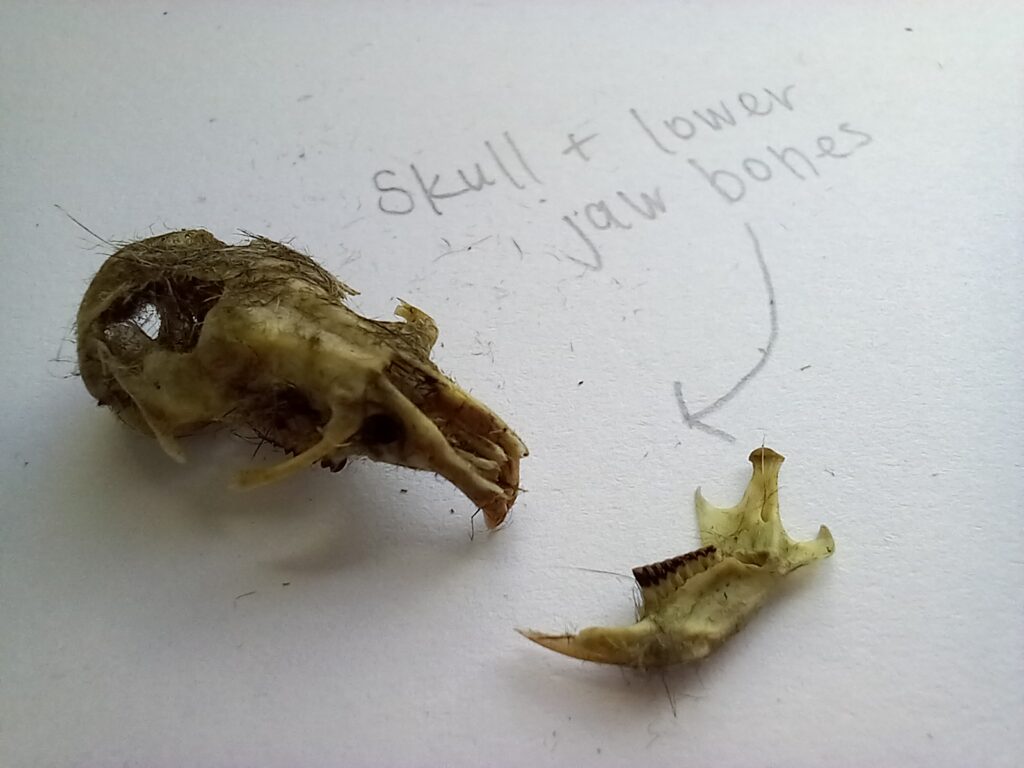

The most useful part of the skeleton for identification is the skull and jaws or beak. Bird skulls will obviously be very distinct from those of mammals due to the presence of the beak, so these can immediately be separated out. For the remaining mammal skulls, however, we will need to take a closer look at their lower jaw bones and teeth.

The most useful part of the skeleton for identification is the skull and jaws or beak. Bird skulls will obviously be very distinct from those of mammals due to the presence of the beak, so these can immediately be separated out. For the remaining mammal skulls, however, we will need to take a closer look at their lower jaw bones and teeth.