Caterpillars are part of the life cycle of moths or butterflies which is known as complete metamorphosis. This life cycle includes four stages: egg, caterpillar (also known as the larval or feeding stage), pupa (the transition stage) and adult (the reproductive phase). With over 2,600 species of moth and 60 species of butterfly in the British Isles, there are a large variety of caterpillars present in our countryside.

There are several stages of caterpillar growth called instars, during which the caterpillar sheds its skin as it grows. Colouration, size and patternation can vary between these instars. Additionally, species can have different variations of caterpillars, including different colour forms. Several species are listed below, grouped by key characteristics such as colour, patternation and features.

Hairy caterpillars

There are many ecological functions of hair-like structures on caterpillars including defence and camouflage. These hairs, called setea, can be almost invisible to the naked eye, while others make them easier to see. Two types of caterpillar hair can cause harm to humans and pets: urticating, which are itchy, non-venomous hairs that can irritate the skin, and stinging hairs, which are hollow spines that have poison-secreting cells that can cause a range of health issues if they enter the skin.

Knot Grass moth (Acronicta rumicis): Colour can vary between light gingery brown to near black, with patches of rusty brown hair and a broken line of white dorsal patches. They also have a wavy white line on their sides, broken with bright orange/red spots. They grow up to 40mm in length. Can be confused with the caterpillars of Brown-tail and Yellow-tail moths. Foodplants include Knot Grass as well as Broad-leaved Dock, plantains, Bramble, Hawthorn, Common Sorrel, heather, and Purple Loosestrife.

Fox Moth (Macrothylacia rubi): Very hairy, up to 70mm long, dark brown with an orangey stripe down the length of its body. Caterpillars in earlier stages of development may have distinctive orange or yellow bands. Commonly feeds on heathers, Bilberry, Creeping Willow, Bramble, Meadowsweet and Salad Burnet.

Garden Tiger moth (Arctia caja): Also known as the woolly bear caterpillar due its very long hairs. Grows up to 55mm long and has a dark red dorsal area with white tipped hairs,an orangey red underside, and small white markings along its sides. Feeds on a variety of herbacious and garden plants including Common Nettle, Broad-leaved Dock, burdocks and Hound’s-tongue.

Brown-tail moth (Euproctis chrysorrhoea): Can measure up to 30mm long, black with white markings down its sides and two distinctive orangey red ‘warts’ on its back near its tail. Be aware that its hairs are toxic to humans. Feeds on plants in the Rosaceae family including Hawthorn, Blackthorn, Plum, Cherry, Rose and Bramble.

Miller moth (Acronicta leporina): Up to 35mm long with very long white or yellow hairs that swirl to one side. The body is often a pale green to brown depending on the development stage but this can be hard to see under the hairs. Usually found on birch or Alder trees.

Pale Tussock moth (Calliteara pudibunda): Greenish yellow hairs with a black body showing through in bands between tufts. The hairs can vary in colour and can be white, brown or pink. They also have a tail tuft that varies in colour but is usually brown, pink or red. This can be absent in some individuals. The four, tussocky tufts on their dorsal are frequently white, brown or yellow. Feeds on a variety of broadleaved trees and shrubs including Hawthorn, Blackthorn, Crab Apple, oaks, birches and Hazel.

Sycamore moth (Acronicta aceris): Up to 40mm long with thick hair that is either yellow, brown or orange . They have bold white spots down their back, outlined in black, as well as tufts of dark orange or bright red hair on their back. Foodplants are most commonly Sycamore, Field Maple and Horse-chestnut.

White Ermine moth (Spilosoma lubricipeda): Approximately 40mm long with a red, orange or pale dorsal line. Caterpillars at later development stages are covered in spines that can be reddish brown, dark brown or even black.

Brown caterpillars

Elephant Hawk-moth (Deilephila elpenor): Thick bodies that grow up to 8cm in length, usually dark brown but bright green forms also occur. The name derives from their smaller, trunk-like head that extends from its more bulbous neck. They feature a spiked tail and four eyespots, although the second pair can be less visible on darker individuals. Most frequently found on Rosebay Willowherb, Great Willowherb, other willowherbs and bedstraws.

Square-spot Rustic moth (Xestia xanthographa): Greenish ochre in colour, with pale lines on its back and edged with dark, long, slanted markings on its sides in a row. Mainly feeds on grasses, plantains and Cleavers.

Large Yellow Underwing moth (Noctua pronuba): Grows to a length of 45–50mm. Its body can be various shades of brown and green, with three lines down its back and dark patches on the inner side of the outer two lines – similar to the Square-spot Rustic. They also have darker sides with a lighter stripe above the legs. Feeds on a wide range of herbaceous plants and grasses including docks, brassicas, marigolds and Foxglove.

Dot Moth (Melanchra persicariae): These caterpillars can reach up to 45mm in length and can be different shades of brown and green. They have three pale, distinctive lines on the dark prothoracic plate behind their head, as well as dark and light chevrons along a pale dorsal line down their backs. Feeds on a wide range of herbaceous and woody plants including Common Nettle, White Clover, Ivy, Hazel, Elder and willows.

Many of these caterpillars can also have a green form.

Black and yellow/orange patterned caterpillars

Large White butterfly (Pieris brassicae): Pale green-yellow in colour with black spots along its body. Visibly hairy. Also known as a Cabbage White due to its preference for cabbages as a food plant.

Buff-tip moth (Phalera bucephala): Distinctive caterpillar with a trellised black and yellow patterning and covering of pale hairs. The face is black and has an inverted yellow V. When fully grown this caterpillar measures up to 75mm in length. Most frequently found on sallows, birches, oaks and Hazel.

Six-spot Burnet moth (Zygaena filipendulae): Caterpillars feature a series of yellow and black dots on a green or greenish-yellow body. Feeds on Common Bird’s-foot-trefoil or occasionally Greater Bird’s-foot-trefoil.

Small Tortoiseshell butterfly (Aglais urticae): Caterpillars are initially black but show increasing variation in colour, with many developing pale yellow lines down their back and sides (some, however, may remain pure black). They have small clusters of short yellow spines and are fully grown at 30mm. Usually found on Common Nettle leaves.

Mullein moth (Curcullia verbasci): One of the most striking and distinctive caterpillars to be found in Britain, they have a mixture of repeating black and yellow markings on a pale bluish-grey body. When fully grown they measure almost 50mm in length. Foodplants include mulleins, Common Figwort, Water Figwort and buddleias.

Box Tree moth (Cydalima perspectalis): Box Tree moths were introduced accidentally from south-east Asia and are a pest of Box trees. Caterpillars have green and black stripes running the length of the body, and the head is shiny black. Each of the body segments has white hairs and eyelike markings.

Black and spiky caterpillars

Peacock butterfly (Aglais io): Unlike the brightly coloured adult Peacock butterfly, the Peacock caterpillar has a velvety black body with small white spots and short spines on each segment. Most commonly feeds on Common Nettle and Hops.

Painted Lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui): Often found on thistles, Painted Lady caterpillars live for 5-10 days in a loosely woven silk nest inside which they feed continuously. They have dark bodies with pale narrow yellow-cream stripes. Particularly on younger larvae, spines can be alternating light and dark.

Marsh Fritillary butterfly (Euphydryas aurinia): Caterpillars are black and hairy and initially live in groups on a larval web which is woven on the bottom-most leaves of Devil’s Bit Scabious plants. Prior to pupation, at the end of April, caterpillars will finally disperse to live independently.

Red Admiral butterfly (Vanessa atalanta): Caterpillars are black and spiny with a yellow stripe down each side and fine hairs along the body. They can be tricky to spot as they use silk to bind nettle leaves together to make a protective tent inside which they feed.

Green caterpillars

Lime Hawk-moth (Mimas tiliae): Caterpillars are distinctive having a large green body with pale yellow streaks on each segment and a bluish ‘horn’ at the tail end. Turns purple a short time before pupation. Foodplants include Limes, elms, Downy Birch, Silver Birch and Elder.

Poplar Hawk-moth (Laothoe populi): A thick and chunky, bright green caterpillar with faint yellow lines running diagonally along the body. The tail end has a yellow ‘horn’ and some individuals have small, dark spots. Food plants include poplars, sallows and willows.

Privet Hawk-moth (Sphinx ligustri): Bright, lime-green caterpillar with white and purple stripes and a pale yellow spot on each segment. The tail end has a black curved hook. Usually found on Wild and Garden Privets, Ash, Lilac and Guelder-rose.

Eyed Hawk-moth (Smerinthus ocellata): Closely resembles the Poplar Hawk-moth caterpillar in that it is bright green with diagonal yellow lines. When mature it can be distinguished by its bluish tail horn. Foodplants include Apple, willows and sallows.

Speckled Wood butterfly (Pararge aegeria): Bright green with faint dark green and yellow stripes running longitudinally along the length of the body. Feeds on False Brome, Cock’s-foot, Yorkshire-fog and Common Couch.

Pine Hawk-moth (Sphinx pinastri): Dark green caterpillar with a brown stripe along the centre of its back and cream dashes that run either side of this. It has a brown head and a black tail horn. Feeds mainly on Scots Pine.

Bright-line Brown-eye moth (Lacanobia oleracea): Green caterpillar with a bright yellow line along its sides and tiny black spots. Found on a variety of herbacious and woody plants such as Common Nettle, Fat-hen, willowherbs, Hazel and Hop. Sometimes a pest of cultivated Tomatoes.

Hummingbird Hawk-moth (Macroglossum stellatarum): Caterpillars are mainly green and have a thick, cream-yellow stripe running along the sides with a white line above. The tail horn is black with a yellow tip when mature. Feeds on Lady’s Bedstraw, Hedge Bedstraw and Wild Madder.

Straw Dot moth (Rivula sericealis): Green caterpillar with two cream stripes running along the back creating a repeating hourglass pattern between them. Covered in long fine hairs. Not often seen, the caterpillars feed on a variety of grass species.

Silver Y moth (Autographa gamma): Relatively easy to identify as it has only two sets of prolegs (small fleshy stubs beneath the body) and a rear clasper which means it walks with an arched body. It has a green body with a series of white wavy lines which may be broken by pale circles in later instars. Feeds on a range of low-lying herbacious plants including bedstraws, clovers, Common Nettle, Garden Pea and Cabbage.

Kentish Glory moth (Endromis versicolora): Large green caterpillar with diagonal pale stripes on each segment. Usually found on Silver Birch and less often on Downy Birch and Alder.

Emperor Moth (Saturnia pavonia): Green with black hoops containing yellow wartlike spots. Common in scrubby places whether they often feed on heathers, Meadowsweet, Bramble, Hawthorn and Blackthorn, amongst others.

Angle Shades moth (Phlogophora meticulosa): Usually green but can be mixed with shades of brown and/or yellow. A fine pale line runs down the back and a pale band runs down the sides of the body. Foodplants include a range of herbaceous and woody plants such as Common Nettle, Hop, Red Valerian, Bramble and Broad-leaved Dock.

Others

Swallowtail butterfly (Papilio machaon): Striking bright green caterpillar with black bands and orange spots. British Swallowtail caterpillars feed solely on Milk-parsley.

Cinnabar moth (Tyria jacobaeae): Easy to identify having bold gold and black stripes. Most commonly feeds on the leaves and flowers of Common Ragwort where they can be found in their hundreds.

High Brown Fritillary butterfly (Argynnis adippe): Black caterpillar with a checkered pale pattern and yellow/buff spines. Covered in fine black bristles. Feeds on Common Dog-violet and Hairy Violet.

Magpie moth (Abraxas grossulariata): Distinctive caterpillar with a creamy-white body, rows of black and white spots and an orange stripe that runs along the length of the body on the lower sides. Feeds on a range of deciduous trees such as Blackthorn, Hawthorn and Hazel as well as currant and gooseberry bushes.

Small Copper butterfly (Lycaena phlaeas): Slug-shaped caterpillar covered in tiny white hairs. Exists in two forms: a purely green form and a green and pink striped form. Main foodplants are Common Sorrel and Sheep’s Sorrel.

Comma butterfly (Polygonia c-album): Mainly coloured brown and black with a large white mark towards the rear end of its back. Preferred foodplant is Common Nettle.

Yellow-tail moth (Euproctis similis): Black caterpillar with a small hump behind its head. Two red/orange lines run along the back with a row of white markings wither side of them. They are covered in long black hairs and shorter white ones. Feeds on a wide selection of broadleaf trees and shrubs including Hawthorn, Blackthorn, oaks, roses, Hazel and willows.

Lackey moth (Malacosoma neustria): Large orange, blue and white striped caterpillars that are covered with fine orange hairs. Often feed in large groups on broadleaved trees and shrubs including Blackthorn, Hawthorn, cherries, Plum and Apple.

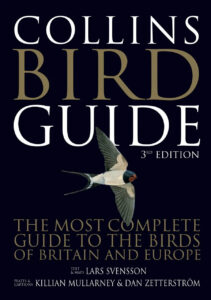

Recommended Reading:

Field Guide to the Caterpillars of Great Britain and Ireland

Field Guide to the Caterpillars of Great Britain and Ireland

This Bloomsbury Wildlife Guide allows identification of the common moth and butterfly caterpillars of the British Isles.

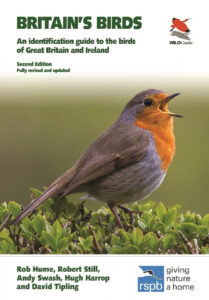

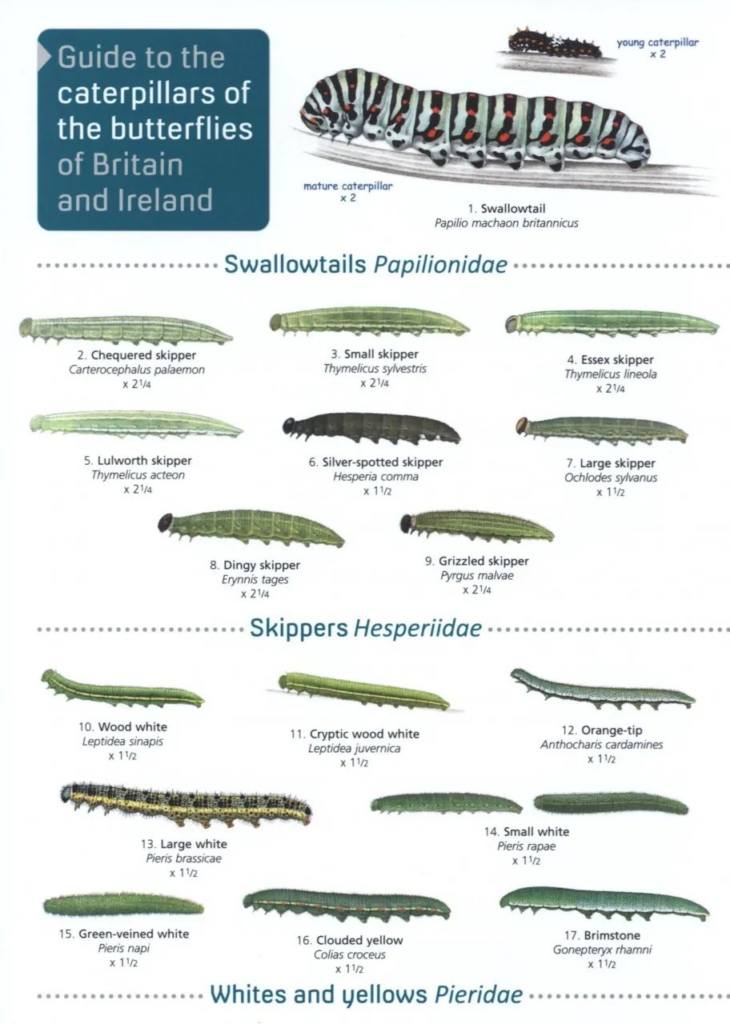

A Guide to the Caterpillars of the Butterflies of Britain and Ireland

A Guide to the Caterpillars of the Butterflies of Britain and Ireland

A second edition fold-out guide to 57 of Britain’s butterfly species.