Introduction.

Choosing the right binoculars for either your hobby or work is something you should spend time on. While using binoculars on dry land sometimes has challenges with poor weather conditions, if you then wish to use a pair of optics out at sea, you should consider some additional points.

Choosing the right binoculars for either your hobby or work is something you should spend time on. While using binoculars on dry land sometimes has challenges with poor weather conditions, if you then wish to use a pair of optics out at sea, you should consider some additional points.

Wind, changing light conditions and weight are amongst the deciding factors on what makes a good pair of optics but add variable movement and changing landscapes to the list of elements to assess a pair of binoculars and you need to review your selection even more carefully. I’m very lucky to be able to have access to a boat for cetacean spotting and surveying. With that in mind, I decided to put the Hawke Maritime 7 x 50 binoculars through a test. But one thing that always makes it a challenge is the sea state, coupled with fast-changing light and weather conditions. Many of the points outlined below still form part of the normal considerations for use on land, but I’ve tried to extend the thoughts to the case of ‘at sea’.

What to look for in a pair of marine binoculars?

Crisp image

I have found that some binoculars are let down, not by the amount of light going through the lens elements, but by the overall quality of the image. While a bright image is important, chromatic aberrations can cause issues with the identification of surface or flying objects, especially when they are near the edge of the field of view. When the sea state is above 1 (calm or glass-like), there is more movement in the wave height and the amount of time you have to determine the object on the far side of the wave is reduced. Is it a bird, or a dorsal fin? At certain times of the year, it becomes even more of a challenge when you have adult guillemots on the surface of the water with their black and white bodies that can look like the dorsal fins of cetaceans.

This is also important with the large field of view. Maritime binoculars are all about the amount of vision you have. If you are a skipper on a boat and need to make decisions that affect the safety of your vessel, then seeing more of what is at a distance from you is critical. The choice of a BaK-4 Roof prism also plays into the quality of the image as this design of prism is reserved for higher-end products, and it shows with the quality of the image.

Brightness

The overall brightness of the image in all weather conditions is a big help. Timed survey periods for cetaceans rely on the confidence of the surveyor in deciding what they have seen. Whether the light is behind you or in front, the subject brightness needs to be enough to see markings, details of any dorsal fin damage (nicks, cuts), and for the assessment of age. Typically, the youngest calf will have fetal folds on its body, and a bright image will assist in making out those factors to allow assessment of age as they lose these folds after about six months. The Hawke Endurance ED Marine binoculars come in two sizes of front element, the larger giving a brighter image, but at the cost of weight (see below) with the larger binoculars being over 50 per cent heavier than the smaller version. I tested the 7 x 50 version which did not disappoint in brightness and, in my opinion, worth the cost in weight.

Wide field of view

The difference between the two main pairs of binoculars in the range from Hawke is dictated by size. The smaller version (not tested) is lighter in weight and contains a smaller front element (less brightness compared with their larger version) but with a greater field of view. This may be part of your decision for the selection as it is worth remembering that the amount of extra view may not be as much as you first thought. A useful tip to remember is that one degree of field of view equates to about 17.5 meters at a distance of 1000 meters. So the difference between the two versions of the maritime product is just under 23 meters of view!

Waterproof

Waterproof

The binoculars have been rated IP67. Technically they are waterproof and can be immersed in water for a short period of time without any problems. Hawke have given consideration to this by adding a set of float-assisted neck straps. Coloured bright yellow, it makes it easy to spot should you accidentally drop them over the side of the boat. The strap will keep them afloat. Needless to say, I didn’t test this benefit! It is also worth keeping a cloth with you for wiping away the salt water as, no matter how durable a pair of binoculars can be, sea spray will eventually damage the product.

Weight

The 7 x 50 binoculars compared with many others are no heavier than the average. However, my view on weight is reflected by the circumstances of use. If you intend to use them on a boat, and the conditions are less than calm, then holding them with one hand while using your other hand for stability is a great test. Long periods of time holding them in one hand can start to strain the wrist. Using the neck strap is important.

Conclusion

I found the 7 x 50 binoculars to be a joy to use. Overall, the specifications have been well thought through, and provide the majority of what you would need to survey. They even produce a version with a compass built in, which I can imagine would be a further benefit for recording the sighting direction when surveying. They are comfortable to hold and generate a bright image, making it easy to identify the subject matter. It should also be noted that Hawke provide a lifetime warranty on product defects, which I feel is an outstanding part of the manufacturer’s services.

The Hawke Endurance ED Marine Binoculars can be found here. Our full range of Hawke Optics binoculars can be found here.

If you have any questions about our range or would like some advice on the right product for you then please contact us via email at customer.services@nhbs.com or phone on 01803 865913.

Wooden bat boxes

Wooden bat boxes  Woodstone and woodcrete bat boxes

Woodstone and woodcrete bat boxes Eco-plastic bat boxes

Eco-plastic bat boxes

There are also pole-mounted bat boxes (sometimes known as rocket boxes). These bat boxes are helpful alternatives in areas where there is nowhere to mount the bat box. An additional benefit is that they ensure that the bat box gains maximum sunlight in shaded areas.

There are also pole-mounted bat boxes (sometimes known as rocket boxes). These bat boxes are helpful alternatives in areas where there is nowhere to mount the bat box. An additional benefit is that they ensure that the bat box gains maximum sunlight in shaded areas. Lastly, there are bat roost access titles and bricks. These are designed to provide bats with access points within roof or ridge tiles. Some bats will roost in the confined spaces beneath the tiles and others will use the open roof space to roost.

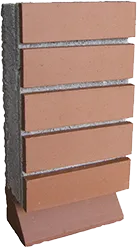

Lastly, there are bat roost access titles and bricks. These are designed to provide bats with access points within roof or ridge tiles. Some bats will roost in the confined spaces beneath the tiles and others will use the open roof space to roost.