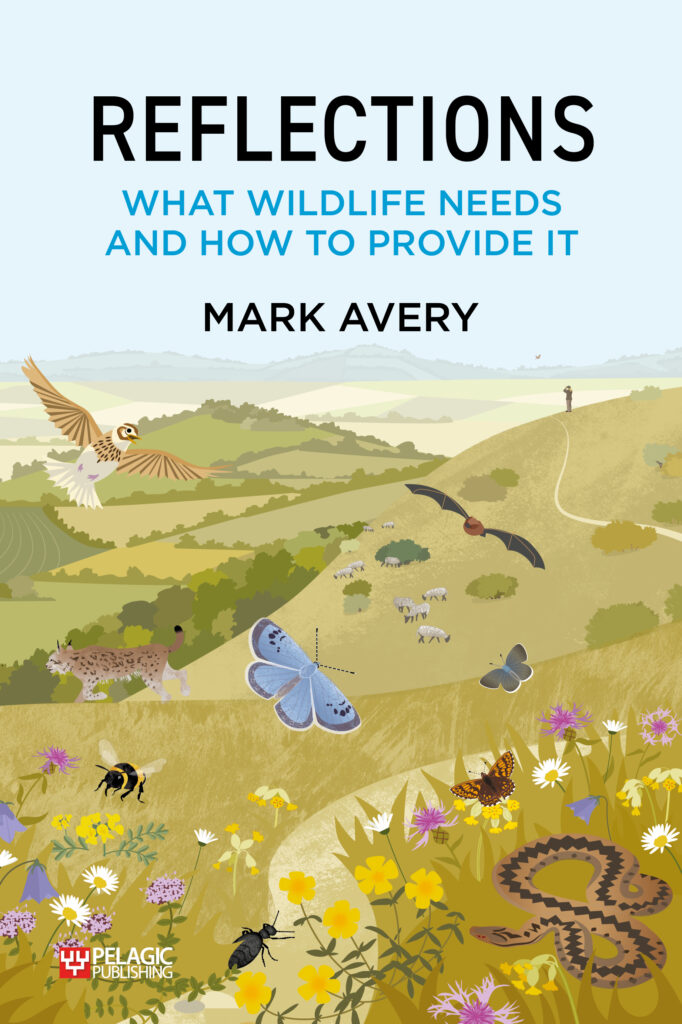

Reflections is a passionate commentary on the state of nature and conservation in the UK. In it, Dr Mark Avery explores the current condition of wildlife, why wildlife conservation is failing and what can be done to reverse its plight. He examines the role NGOs, land owners and government have in its failure, and crucially examples of successes too. Reflections is a valuable resource for those wondering what exactly is going wrong in nature conservation and what action can be taken to remedy this.

Reflections is a passionate commentary on the state of nature and conservation in the UK. In it, Dr Mark Avery explores the current condition of wildlife, why wildlife conservation is failing and what can be done to reverse its plight. He examines the role NGOs, land owners and government have in its failure, and crucially examples of successes too. Reflections is a valuable resource for those wondering what exactly is going wrong in nature conservation and what action can be taken to remedy this.

Mark Avery is an author, blogger and former director of conservation at the RSPB where he worked for 25 years. His previous works include Inglorious where he examines grouse shooting in the British uplands, and Remarkable Birds, a compendium showcasing the extraordinary wonders of the birds that share our world. We had the opportunity to speak to Mark about how he came to write Reflections and some of the key themes from the book.

Could you tell us about how you came to write Reflections?

I guess there are at least three reasons for writing a book. First, that you have a great imagination and can tell scintillating stories. Well, that’s not me and I write non-fiction, though I have wondered about a fictional book about nature conservation and nature conservationists. Second, you have some amazing experiences that you want to share with the world. That’s not me either. Third, you think you have ideas about the world that will be useful to others, and that’s the category that Reflections is in. I have worked in wildlife conservation for over three and a half decades and so I’ve lived the issues about which I write, but I’m not writing about my experiences, I’m writing about my thoughts, ideas and take on the world. Those ideas were bubbling up so much that I thought I’d write them down. It felt a bit like a pressure valve being released. The good thing from my point of view is that it seems that lots of other people relate to my thoughts. That’s thrilling for any author.

How do you think people’s attitudes towards, and awareness of wildlife have changed in your lifetime?

I was a teenager 50 years ago so looking back to then, animal welfare concerns, which aren’t quite the same as conservation concerns but are mixed together in all of our heads, have grown enormously. That affects how people think of field ‘sports’, predator control, snaring etc. I welcome many of those changes in attitude. Climate change has come along and dominates, rightly, the environment scene, and that has implications for wildlife conservation. I sometimes think that nature conservation is a bit squeezed between welfare issues and hard environmental ones. But over that period conservationists have moved from playing in small nature reserves and chasing people persecuting wildlife, to a greater force having some influence (not enough!) on big public policies such as farming, forestry and fisheries. We need to develop more strength in those political realms if we are to see nature recover.

You talk in Reflections about situations where considerable gains in wildlife conservation can be obtained in exchange for small losses in profit from land use activities. How do you think land managers can be convinced to take the hit to their profits for the benefit of wildlife?

With respect, I don’t accept the premise of the question. It is utterly pointless to try to get a vested interest like agriculture (house building, private forestry, shooting etc.) to act for the public good. Our wildlife conservation bodies are too timid and nice to realise that is a dead end. One has to jump over the heads of such industry representatives and persuade the decision-makers directly to implement public policies that deliver public goods. Focus effort on the decision-makers!

In the book you frequently mention the trade-offs between the state of wildlife in the UK and living standards. How do you think we can we balance the need for government investment in wildlife conservation and in critical public services like the NHS?

I’m glad you noticed that – we live in a complex human world and most people don’t give a stuff about wildlife. The partial answer to that question is that spending on wildlife conservation is tiny – that’s why it doesn’t work very well. It could increase many times over and still be tiny compared with other expenditures. It would be a false dichotomy to say we can have either a thriving wildlife or a thriving NHS, but I concede at the moment neither is thriving. Another partial answer is that governments should use more regulation (‘thou shalt not’s) rather than spending money on persuasion. They are cheap for the public purse. And of course, there are real benefits, that have economic valuations, in having wildlife-rich landscapes that flood less (or less damagingly), store more carbon and make people happier. But it’s a big subject. Give me a list of government spending across departments and I’ll cross a few things out (I might start with nuclear warheads) but your list would be different from mine, I guess.

You mention that the number of people actively interested in wildlife conservation is relatively small. How can we get more people to care about wildlife in the UK?

This is what our wildlife NGOs would call recruitment, or growing their memberships. The trouble is, it’s easier to recruit members than committed members interested in nature conservation. The National Trust’s five million members are arguably a weaker force for good that Wild Justice’s zero members but 35,000+ newsletter readers (but I’m maybe biased there). I think we could get more nature conservation done, particularly more impact on government policies, by getting existing members more mobilised than we could by getting more members. We have a small army of devoted conservationists – it’s just that they aren’t well armed with facts and tasks. Having more badly equipped troops isn’t a great recipe for success, I feel.

Do you think it is likely that we will see an improvement in the state of wildlife in the UK?

I can’t say that it is likely but it is certainly possible – but impossible with business as usual. We, and this means our largest wildlife charities, need to get much better at influencing land use policies. That’s entirely feasible but needs a change of mindset. I hope Reflections will encourage that change of mindset.

Do you have any plans for further books that you can tell us about?

I always have ideas, I have two at the moment, but sometimes they come to nought, so I’m not telling! Watch this space!

Reflections by Mark Avery is now available in hardback and paperback from nhbs.com.

Interwoven throughout with tales of his experiences moth trapping on his London rooftop and in the Devon countryside, The Jewel Box by Tim Blackburn introduces us to a range of ecological theories and explains some of the where, why and hows that anyone curious about the natural world might tend to ponder upon. Beautifully and engagingly written, it manages to be both an ode to both the moths themselves and the activity of moth trapping, as well as a wider ranging exploration of the relationships between humans, other species and habitats.

Interwoven throughout with tales of his experiences moth trapping on his London rooftop and in the Devon countryside, The Jewel Box by Tim Blackburn introduces us to a range of ecological theories and explains some of the where, why and hows that anyone curious about the natural world might tend to ponder upon. Beautifully and engagingly written, it manages to be both an ode to both the moths themselves and the activity of moth trapping, as well as a wider ranging exploration of the relationships between humans, other species and habitats. Professor Tim Blackburn is a scientist with thirty years of experience studying questions about the distribution, abundance and diversity of species in ecological assemblages. He is currently a Professor of Invasion Biology at University College London, where his work focuses on alien species. Before that, he was the Director of the Institute of Zoology, the research arm of the Zoological Society of London.

Professor Tim Blackburn is a scientist with thirty years of experience studying questions about the distribution, abundance and diversity of species in ecological assemblages. He is currently a Professor of Invasion Biology at University College London, where his work focuses on alien species. Before that, he was the Director of the Institute of Zoology, the research arm of the Zoological Society of London.

An Identification Guide to Garden Birds of Britain and North-West Europe is a photographic guide to 75 species of bird most commonly found in or over the gardens of Britain and North-West Europe. The text combines scientific facts with affectionate descriptions of the birds’ identifying features, including sex and age differences, habits, nest types, eggs and calls. The introduction contains tips on how to identify birds, how to look after garden birds, which species can be seen throughout the year, a glossary and anatomy details. For each species, there are two or three photographs labelled with distinguishing features where appropriate, a calendar showing the time of year when the adult can be seen and star facts that give further proof of the birds’ fascinating features.

An Identification Guide to Garden Birds of Britain and North-West Europe is a photographic guide to 75 species of bird most commonly found in or over the gardens of Britain and North-West Europe. The text combines scientific facts with affectionate descriptions of the birds’ identifying features, including sex and age differences, habits, nest types, eggs and calls. The introduction contains tips on how to identify birds, how to look after garden birds, which species can be seen throughout the year, a glossary and anatomy details. For each species, there are two or three photographs labelled with distinguishing features where appropriate, a calendar showing the time of year when the adult can be seen and star facts that give further proof of the birds’ fascinating features.

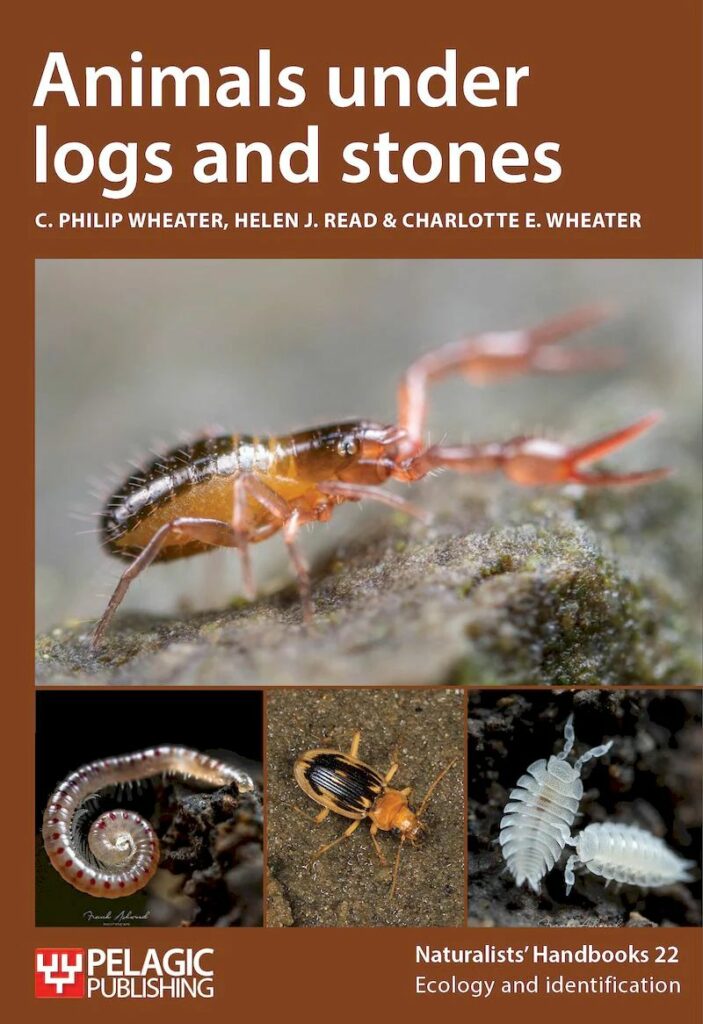

Helen Read is a Conservation Officer for the City of London Corporation based at Burnham Beeches, a post held for over 30 years. She has written numerous books and papers on a variety of subjects, the majority being on the management of veteran trees and topics relating to invertebrates. She has also been an active committee member in various invertebrate societies.

Helen Read is a Conservation Officer for the City of London Corporation based at Burnham Beeches, a post held for over 30 years. She has written numerous books and papers on a variety of subjects, the majority being on the management of veteran trees and topics relating to invertebrates. She has also been an active committee member in various invertebrate societies.

The Book of Wilding, while being a hugely practical guide to rewilding on all scales, is also a beacon of hope. In an age when eco-anxiety can lead even the most optimistic and determined of us to feel despondent, do you feel broadly hopeful that humans can do the necessary work to restore balance to our planet?

The Book of Wilding, while being a hugely practical guide to rewilding on all scales, is also a beacon of hope. In an age when eco-anxiety can lead even the most optimistic and determined of us to feel despondent, do you feel broadly hopeful that humans can do the necessary work to restore balance to our planet?  Do you think that there are some misconceptions as to what constitutes rewilding? Particularly on a smaller scale where a more hands-on approach might be required to mimic the natural processes of herbivores, for instance – to the untrained eye this might seem more like conventional conservation management than rewilding.

Do you think that there are some misconceptions as to what constitutes rewilding? Particularly on a smaller scale where a more hands-on approach might be required to mimic the natural processes of herbivores, for instance – to the untrained eye this might seem more like conventional conservation management than rewilding.  Finally – what steps would you recommend to the ‘average’ citizen who isn’t a large landowner or farmer and wants to go beyond simply rewilding their own small garden?

Finally – what steps would you recommend to the ‘average’ citizen who isn’t a large landowner or farmer and wants to go beyond simply rewilding their own small garden?