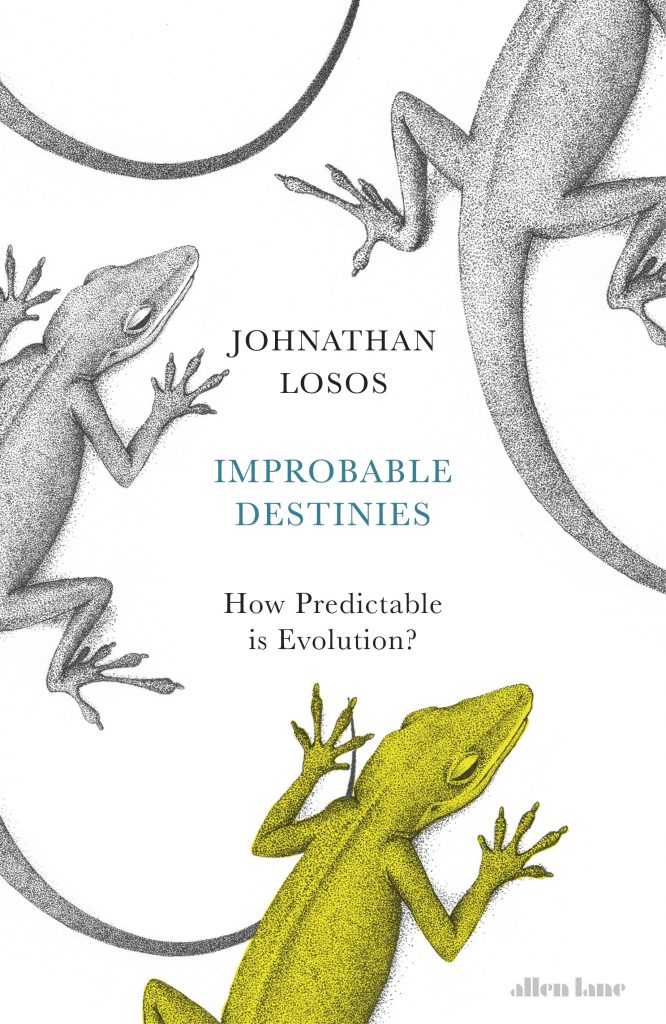

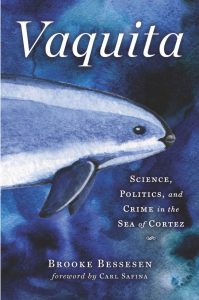

In Vaquita: Science, Politics, and Crime in the Sea of Cortez, author Brooke Bessesen takes us on a journey to Mexico’s Upper Gulf region to uncover the story behind the world’s most endangered marine mammal. Through interviews with townspeople, fishermen, scientists, and activists, she teases apart a complex story filled with villains and heroes, a story whose outcome is unclear.

In this post we chat with Brooke about her investigations in Mexico, local and international efforts to save the vaquita and the current status of this diminutive porpoise.

![]()

The vaquita entered the collective imagination (or at least, my imagination) when it became world news somewhere in 2017 and there was talk of trying to catch the last remaining individuals, something which you describe at the end of your story. Going back to the beginning though, how did you cross the path of this little porpoise?

The vaquita entered the collective imagination (or at least, my imagination) when it became world news somewhere in 2017 and there was talk of trying to catch the last remaining individuals, something which you describe at the end of your story. Going back to the beginning though, how did you cross the path of this little porpoise?

I first heard about vaquita during a visit to CEDO, an educational research station in Puerto Peñasco, Mexico. I was enchanted to discover this beautiful little porpoise was endemic to the Upper Gulf of California, mere hours south of my home, yet saddened to learn it was already critically endangered. I still have the t-shirt I bought that day to support vaquita conservation. That was 2008 when the population estimate was 245.

The last update I could find was an interview in March 2018 on Mongabay with Andrea Crosta, director of the international wildlife trade watchdog group Elephant Action League. He mentioned there might be only a dozen vaquita left. Do you know what the situation is like now?

The last official population estimate was <30, but that was from 2016. With an annual rate of decline upwards of 50 percent, the number is surely much lower. If only we were able to watch the numbers go down in real time, we would all be forced to emotionally experience this sickening loss. But I think there is a (legitimate) fear that if an updated estimate revealed the number to be in or near single digits, key institutions might announce the species a lost cause and pull up stakes. If pecuniary support disappears, it’s game-over. Vaquita has graced the planet for millions of years—we cannot give up the battle to prevent its extinction so long as any number remain.

Once your investigation on the ground in Mexico gets going, tensions quickly run high. This is where conservation clashes with the hard reality of humans trying to make a living. Corruption, intimidation and threats are not uncommon. Was there ever a point that you were close to pulling out because the situation became too dangerous?

Once your investigation on the ground in Mexico gets going, tensions quickly run high. This is where conservation clashes with the hard reality of humans trying to make a living. Corruption, intimidation and threats are not uncommon. Was there ever a point that you were close to pulling out because the situation became too dangerous?

Truth told, my nerves were prickling from start to finish. The emotional fatigue was intense. But having witnessed the gruesome death of Ps2 [the designation given one of the Vaquita carcasses that washed up, ed.], I simply could not turn back. Then as the humanitarian crisis became clear and I was meeting families struggling to raise children in the fray, I was even more committed to telling this story. When courage wavered, I only had to remind myself of the host of social scientists, biologists, activists, and law-abiding fishermen working so bravely for the cause.

You describe a widespread indifference to the vaquita. I have the feeling a lot of this is cultural. Do you think a change in attitude can ever be effected? Or is the combination of poverty and the need to make a living completely at loggerheads with this?

I see two main obstacles to solving the vaquita crisis: corruption and poverty. In that order, because until local citizens can trust their military and police officers to rightfully enforce law, and until Pesca [Mexico’s National Fisheries Institute and its National Commission of Aquaculture and Fisheries, ed.] authorizes legal, sustainable fishing methods instead of providing loopholes for poachers, there will be no economic stability in the region. Money is pouring into the pockets of crime bosses while upstanding folks barely get by. Focused on either greed or survival, nobody has much capacity to care about porpoise conservation. That said, I do believe change can be effected. Several NGOs are already connecting with the communities in meaningful ways, and mind-sets are slowly shifting. If Mexico’s president-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who goes by the nickname Amlo, manages to abolish corruption as he has promised to do, civic finances will balance out and efforts to care for vaquita will find better footing.

As the story progresses, more and more foreign interests enter this story. Sea Shepherd starts patrolling the waters, and Leonardo DiCaprio also gets involved, signing a memorandum of understanding with the Mexican president to try and turn the tide. What was the reaction of Mexicans on the ground to this kind of foreign involvement? Are we seen as sentimental, spoiled, rich Westerners who can afford unrealistic attitudes?

As the story progresses, more and more foreign interests enter this story. Sea Shepherd starts patrolling the waters, and Leonardo DiCaprio also gets involved, signing a memorandum of understanding with the Mexican president to try and turn the tide. What was the reaction of Mexicans on the ground to this kind of foreign involvement? Are we seen as sentimental, spoiled, rich Westerners who can afford unrealistic attitudes?

Since the majority of environmentalists working in the Upper Gulf are Mexican, and even Leonardo DiCaprio had the alliance of Carlos Slim, the socio-political divide does not seem to be so much between nationalists and foreigners as between fishermen and environmentalists. Fishermen who openly expressed distain for “outsiders” disrupting business meant Sea Shepherd, for sure, but they also meant scientists and conservationists from places like Mexico City, Ensenada, and La Paz. Some of the locals I spoke with or followed on Facebook did seem troubled by the amount of resources being spent on vaquita while their own human families suffered. They felt the environmentalists were not appreciating the strain and fear of their jobless circumstances. Then again, a good percentage voiced gratitude for the efforts being made to protect vaquita as a national treasure and seemed to feel part of an important crusade for their country and their community.

Related to this, the West has outsourced the production of many things to countries overseas and so many of us are far removed from the harmful impact that our desire for food and stuff has on the environment. Deforestation in the Amazon to graze livestock for hamburgers is one such long-distance connection that comes to mind. The vaquita has also suffered from the impact of shrimp trawlers. No doubt many who shed tears over the vaquita will happily gorge themselves on said shrimps without ever making the link. Do you think that globalisation has in that regard served to polarise the debate where wildlife and nature conservation is concerned?

Yes, this is a really important point. It’s easy to point fingers, but we are all complicit in the destruction of ocean life. Anyone who eats fish or shrimp caught in gillnets—or trawls, or longlines—is funding the slaughter of cetaceans and sea turtles and myriad other animals. It’s a painful truth. The root of the problem is that most of us don’t know, and don’t care to ask, where the seafood on our dinner plate came from. This is not intended to be accusatory, as I, too, am finding my way in this era of culinary disconnect. I just know the first step is to quit pretending we are bystanders.

One side of the story I found missing from your book was that of the demand for totoaba swim bladders in China. I imagine it might have been too dangerous or time-consuming (or both) to expand your investigation to China as well. How important and how feasible do you think it is to tackle the problem from that side? Without a demand for totoaba bladders, the vaquita wouldn’t face the threats of gillnets after all.

One side of the story I found missing from your book was that of the demand for totoaba swim bladders in China. I imagine it might have been too dangerous or time-consuming (or both) to expand your investigation to China as well. How important and how feasible do you think it is to tackle the problem from that side? Without a demand for totoaba bladders, the vaquita wouldn’t face the threats of gillnets after all.

I think it’s imperative to attack the totoaba trade from the consumer side, with the goal of systematically eliminating the demand for swim bladders. As for feasibility, I’m less confident. Time and distance prevented me from effectively researching the situation in China, but from what I’ve read, the cultural, political, and economic trappings there are just as complicated as they are in Mexico. I’m pleased to know efforts are underway. It also must be said, though, that ending the totoaba trade is not a sure-fire resolution for vaquita because fishermen in the Upper Gulf traditionally use gillnets for a range of legal fish.

With the book now written, are you still involved in efforts to protect the vaquita?

Knowing what I know now, it’s unthinkable to walk away from vaquita. I was down in San Felipe last month, exchanging summer c-pods and catching up on the latest news. Everyone is nurturing the flicker of hope that Amlo will take action to save his national marine mammal by cleaning up the corruption that has stymied vaquita conservation.

![]()

Vaquita: Science, Politics, and Crime in the Sea of Cortez is due for publication in September 2018 and is currently available at the pre-publication price of £19.99 (RRP £22.99).

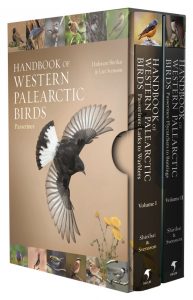

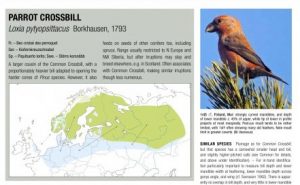

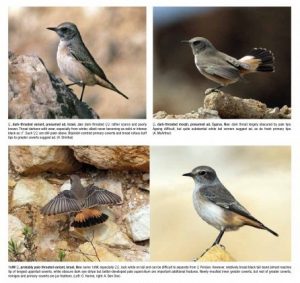

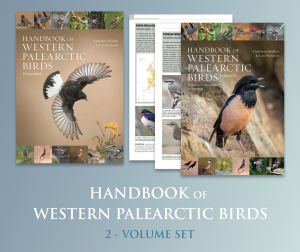

Lars: Let us say that in my case only 15 of these 18 years were spent on the new handbook. I was involved in doing the second edition of the

Lars: Let us say that in my case only 15 of these 18 years were spent on the new handbook. I was involved in doing the second edition of the  Hadoram: At least as I see it, BWP was made some 20-30 years ago when it was still possible to squeeze information into one project – on distribution, population estimates, atlas, ecology, seasonal biology, behaviour, voice, and so on, as well as identification and variation (but with generally only very basic illustrations, paintings) – and to be satisfied with it!

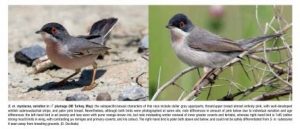

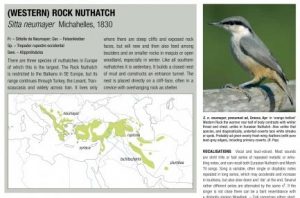

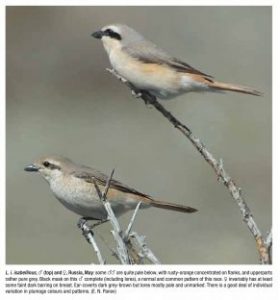

Hadoram: At least as I see it, BWP was made some 20-30 years ago when it was still possible to squeeze information into one project – on distribution, population estimates, atlas, ecology, seasonal biology, behaviour, voice, and so on, as well as identification and variation (but with generally only very basic illustrations, paintings) – and to be satisfied with it! Lars: To assemble the many photographs (there are well over 4000 photographs together in the two passerine volumes) and to achieve full coverage of male and female, young and adult, sometimes also in both spring and autumn, plus examples of distinct subspecies, was of course a major challenge. Hadoram was in charge of this and did a great job, and we got good support from our publisher setting up a home page for the project where photographers could see what we still needed photographs of. Thanks to the prolonged production, many gaps (if not all!) were filled during our course.

Lars: To assemble the many photographs (there are well over 4000 photographs together in the two passerine volumes) and to achieve full coverage of male and female, young and adult, sometimes also in both spring and autumn, plus examples of distinct subspecies, was of course a major challenge. Hadoram was in charge of this and did a great job, and we got good support from our publisher setting up a home page for the project where photographers could see what we still needed photographs of. Thanks to the prolonged production, many gaps (if not all!) were filled during our course. Hadoram: Lars described in his answers very well, the combined efforts with the museum collections work and building the photographic collections and selections for the project.

Hadoram: Lars described in his answers very well, the combined efforts with the museum collections work and building the photographic collections and selections for the project. Lars: Digital photography and the existence of internet and websites for documentation and discussion of bird images are the main changes compared to when I started as a birdwatcher. This has speeded up the exchange of news and knowledge in a remarkable way. True, field-guides and birding journals keep offering better and better advice on tricky identification problems, and optical aids have developed to a much higher standard than say 50 years ago. But the new cameras with stabilised lenses and autofocus have meant a lot and have enabled so-called ‘ordinary’ birders to take excellent photographs. This has broadened the cadre of photographers and multiplied the production of top class images of previously rarely photographed species. Which of course made

Lars: Digital photography and the existence of internet and websites for documentation and discussion of bird images are the main changes compared to when I started as a birdwatcher. This has speeded up the exchange of news and knowledge in a remarkable way. True, field-guides and birding journals keep offering better and better advice on tricky identification problems, and optical aids have developed to a much higher standard than say 50 years ago. But the new cameras with stabilised lenses and autofocus have meant a lot and have enabled so-called ‘ordinary’ birders to take excellent photographs. This has broadened the cadre of photographers and multiplied the production of top class images of previously rarely photographed species. Which of course made  Lars: I have planned for many years now to revise my

Lars: I have planned for many years now to revise my

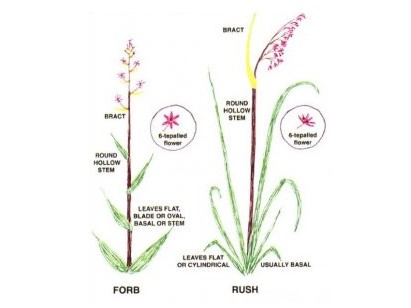

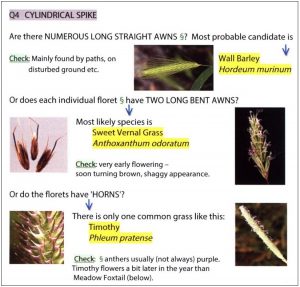

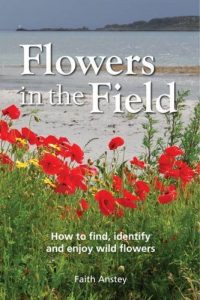

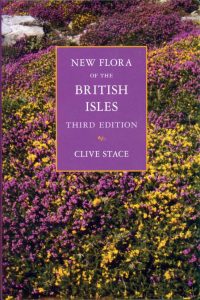

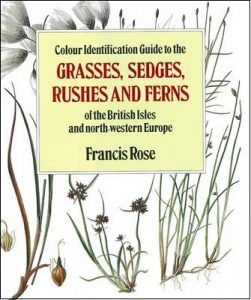

My books are not field guides at all. A field guide gives you a list of plant names, with pictures and descriptions, sometimes with a brief introduction. My books are all introduction: to field botany in general, to plant families and to grasses (maybe sedges and rushes next year . . .). A beginner armed only with a field guide has either to work their way from scratch through complicated keys, or to play snap: plant in one hand, book in the other; turn the pages until you find a picture that matches – ‘snap!’ By contrast, my books lead you into plant identification by logical routes, showing you where to look and what to look for. Their aim is to show you how to do ID for yourself.

My books are not field guides at all. A field guide gives you a list of plant names, with pictures and descriptions, sometimes with a brief introduction. My books are all introduction: to field botany in general, to plant families and to grasses (maybe sedges and rushes next year . . .). A beginner armed only with a field guide has either to work their way from scratch through complicated keys, or to play snap: plant in one hand, book in the other; turn the pages until you find a picture that matches – ‘snap!’ By contrast, my books lead you into plant identification by logical routes, showing you where to look and what to look for. Their aim is to show you how to do ID for yourself.

If you possibly can, go on a workshop for a day, a weekend or even a whole week. Having a real live person giving enthusiastic teaching, someone to answer all your questions and fresh plants to study is the best thing you can do. Look for a local botany or natural history group you can join, and go on their field meetings. When you get even a little more serious about your study, join Plantlife and/or the Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland. Identiplant is a very good online course but it is not really suitable for absolute beginners. Be a bit careful with apps and websites: some are incredibly complex, some seem to be aimed at five-year-olds, others are just inaccurate and misleading. The best ID websites I am aware of are run by the

If you possibly can, go on a workshop for a day, a weekend or even a whole week. Having a real live person giving enthusiastic teaching, someone to answer all your questions and fresh plants to study is the best thing you can do. Look for a local botany or natural history group you can join, and go on their field meetings. When you get even a little more serious about your study, join Plantlife and/or the Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland. Identiplant is a very good online course but it is not really suitable for absolute beginners. Be a bit careful with apps and websites: some are incredibly complex, some seem to be aimed at five-year-olds, others are just inaccurate and misleading. The best ID websites I am aware of are run by the  The main threat is not people picking a few to study, or even simply to enjoy at home. Climate change is, of course, a threat in one sense, but I believe we shouldn’t necessarily dread the rise of ‘aliens’ from warmer climates which are now able to establish themselves here. Every plant in Britain was once an alien, after the last Ice Age ended, and I would rather learn to live with change than blindly try to turn the clock back. There may be a few exceptions like Japanese Knotweed, but their evils are often exaggerated and some natives like bracken can be equally invasive. The real problem we face is habitat loss: to house-building and industry, land drainage, vast monocultural fields without headlands, destruction of ancient forests and so on. And this is an area where watchfulness and action really can make a difference.

The main threat is not people picking a few to study, or even simply to enjoy at home. Climate change is, of course, a threat in one sense, but I believe we shouldn’t necessarily dread the rise of ‘aliens’ from warmer climates which are now able to establish themselves here. Every plant in Britain was once an alien, after the last Ice Age ended, and I would rather learn to live with change than blindly try to turn the clock back. There may be a few exceptions like Japanese Knotweed, but their evils are often exaggerated and some natives like bracken can be equally invasive. The real problem we face is habitat loss: to house-building and industry, land drainage, vast monocultural fields without headlands, destruction of ancient forests and so on. And this is an area where watchfulness and action really can make a difference.

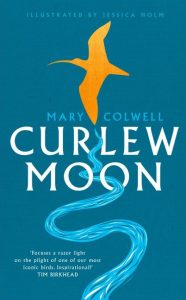

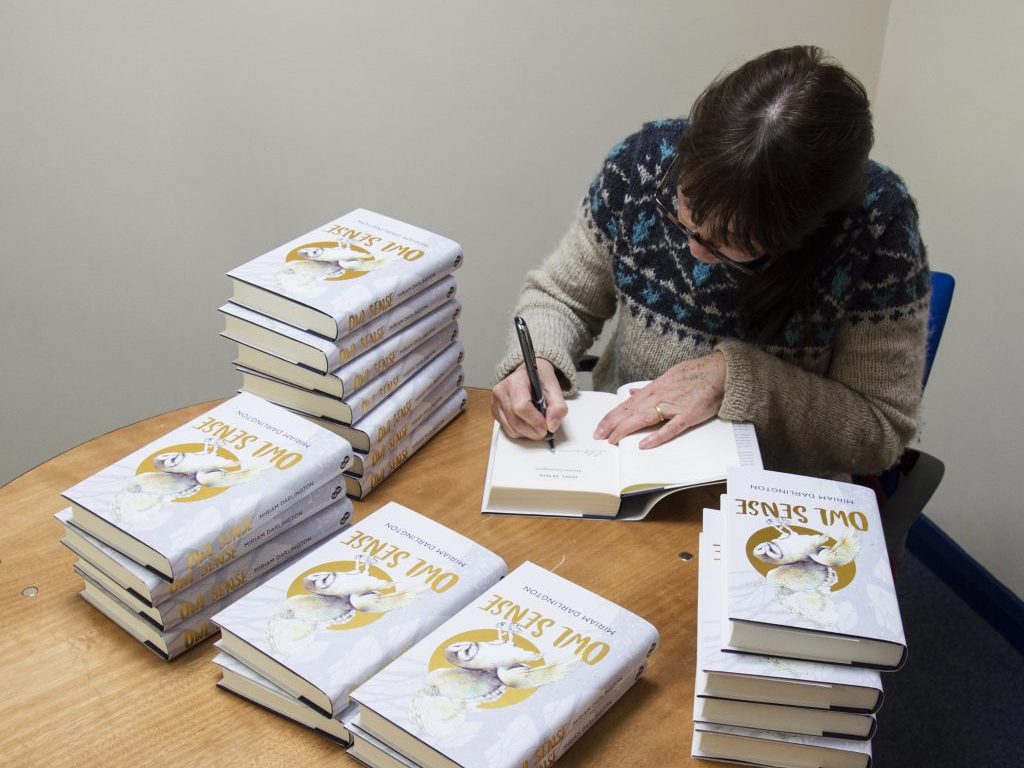

Mary Colwell is an award-winning writer and producer who is well-known for her work with BBC Radio producing programmes on natural history and environmental issues; including their Natural Histories, Shared Planet and Saving Species series.

Mary Colwell is an award-winning writer and producer who is well-known for her work with BBC Radio producing programmes on natural history and environmental issues; including their Natural Histories, Shared Planet and Saving Species series.

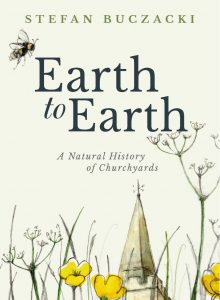

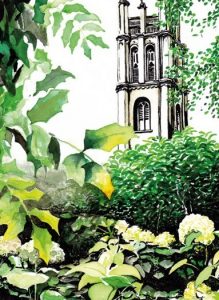

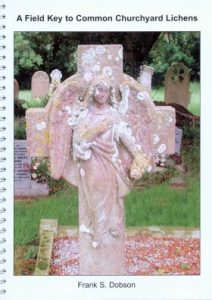

The unique features of churchyards mean that they offer a valuable niche for many species. Enclosed churchyard in particular provide a time-capsule and a window into the components of an ancient British landscape. Well known botanist, mycologist and broadcaster Stefan Buczacki has written

The unique features of churchyards mean that they offer a valuable niche for many species. Enclosed churchyard in particular provide a time-capsule and a window into the components of an ancient British landscape. Well known botanist, mycologist and broadcaster Stefan Buczacki has written

Managing a cemetery in a way that keeps everyone happy seems an impossible job. Last August I was photographing a meadow that had sprung up at a cemetery, when another photographer mentioned how disgusting it was. I was slightly bemused until the man explained he was a town councillor and was disgusted that the cemetery was unmaintained – “an insult to the dead” was how he described it – I thought it looked fantastic! whatever your opinion, how can we achieve common-ground between such diametrically opposed views?

Managing a cemetery in a way that keeps everyone happy seems an impossible job. Last August I was photographing a meadow that had sprung up at a cemetery, when another photographer mentioned how disgusting it was. I was slightly bemused until the man explained he was a town councillor and was disgusted that the cemetery was unmaintained – “an insult to the dead” was how he described it – I thought it looked fantastic! whatever your opinion, how can we achieve common-ground between such diametrically opposed views?

All the significant flora and fauna of churchyards their own chapters or sections; from fungi, lichen and plants, to birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals? Which class, order or even species do you think has the closest association with churchyards and therefore the most to gain or lose from churchyard’s future conservation status?

All the significant flora and fauna of churchyards their own chapters or sections; from fungi, lichen and plants, to birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals? Which class, order or even species do you think has the closest association with churchyards and therefore the most to gain or lose from churchyard’s future conservation status? With church attendance declining and the future of churchyard maintenance an increasingly secular concern; could you give a brief first-steps outline as to how an individual or a group might set about conserving and even improving the natural history of their local churchyard?

With church attendance declining and the future of churchyard maintenance an increasingly secular concern; could you give a brief first-steps outline as to how an individual or a group might set about conserving and even improving the natural history of their local churchyard? If someone, or a group become custodians of a churchyard what five key actions or augmentations would you most recommend and what two actions would you recommend against?

If someone, or a group become custodians of a churchyard what five key actions or augmentations would you most recommend and what two actions would you recommend against?

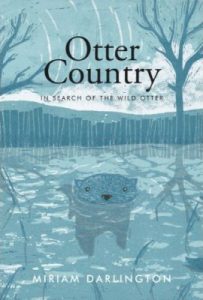

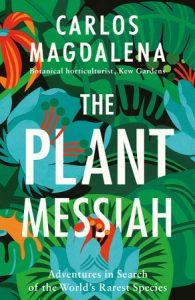

Carlos Magdalena is a botanical horticulturist at Kew Gardens, famous for his pioneering work with waterlilies and his never-tiring efforts to save some of the world’s rarest species from extinction. In his book,

Carlos Magdalena is a botanical horticulturist at Kew Gardens, famous for his pioneering work with waterlilies and his never-tiring efforts to save some of the world’s rarest species from extinction. In his book,

Keith Betton is a keen world birder, having seen over 8,000 species in over 100 countries. In the UK he is heavily involved in bird monitoring, where he is a County Recorder. He has been a Council member of both the RSPB and the BTO, currently Vice President of the latter.

Keith Betton is a keen world birder, having seen over 8,000 species in over 100 countries. In the UK he is heavily involved in bird monitoring, where he is a County Recorder. He has been a Council member of both the RSPB and the BTO, currently Vice President of the latter.