Woodland Flowers: Colourful Past, Uncertain Future is the eighth instalment of the popular British Wildlife Collection. In this insightful and original account, Keith Kirby explores the woodland plants of Britain living in the shade of their bigger relatives. They add so much to woodland’s biodiversity and beauty and tell us stories about the history of woodland, its past management, and how that has changed – not always for the better.

Woodland Flowers: Colourful Past, Uncertain Future is the eighth instalment of the popular British Wildlife Collection. In this insightful and original account, Keith Kirby explores the woodland plants of Britain living in the shade of their bigger relatives. They add so much to woodland’s biodiversity and beauty and tell us stories about the history of woodland, its past management, and how that has changed – not always for the better.

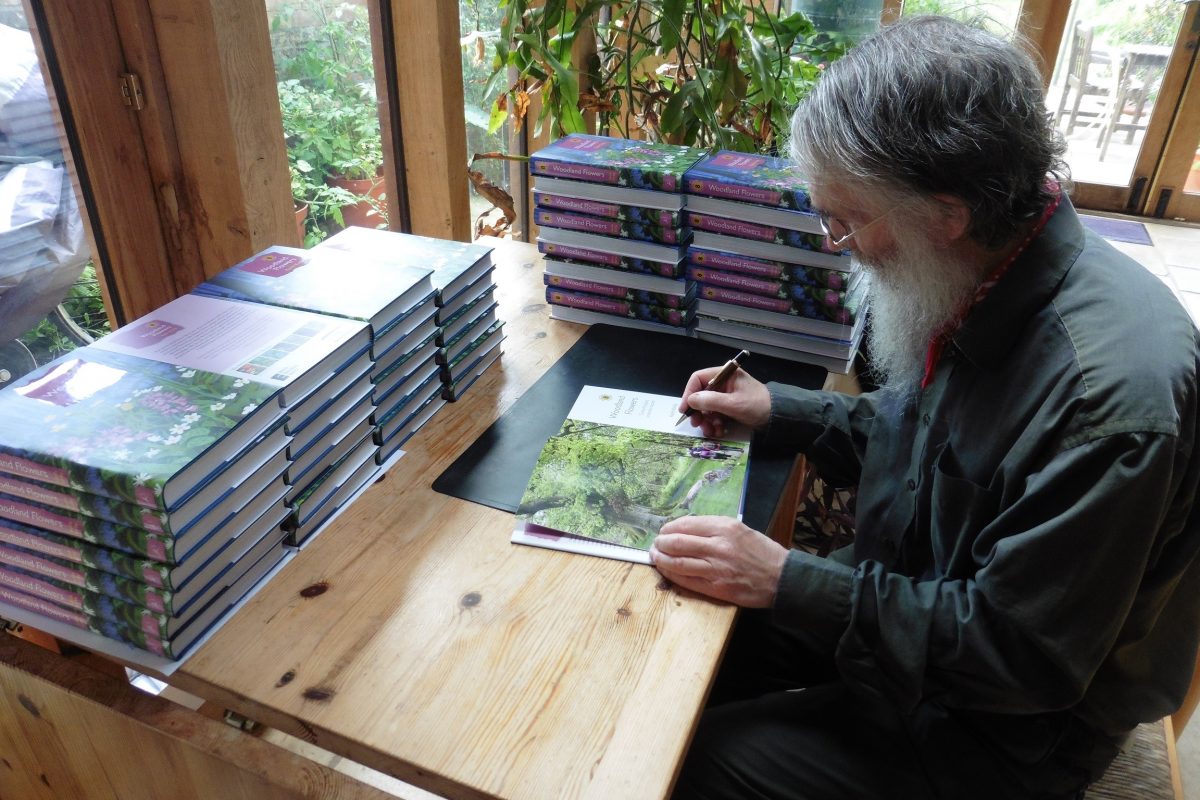

Author, Keith Kirby has taken the time to sign limited copies of Woodland Flower and has answered our questions about the book, and the flowers that enhance our woodlands.

Could you tell us a little about your background?

I grew up in a village in Essex and spent much of my childhood playing in the fields, along the riverbank and in small woods behind our house. I was interested in natural history but not really a serious naturalist. Sometime in my teens I decided I wanted to be a forester and ended up doing a degree in Agricultural and Forest Sciences in Oxford. That introduced me to ‘ecology’ and led to a doctoral study of the growth of brambles in Wytham Woods. From there I spent a couple of years doing woodland and general habitat surveys before getting a permanent post in 1979 with the Nature Conservancy Council as a woodland ecologist. I stayed in that post (NCC became English Nature, became Natural England) through to 2012, then retired back to Oxford and picked up my plant research interests in Wytham Woods again.

Where did the motivation for this book come from? Are woodland flowers a subject that you have been wanting to write about for some time?

Where did the motivation for this book come from? Are woodland flowers a subject that you have been wanting to write about for some time?

Much of my work with NCC and its successor bodies involved considering the woodland ground flora: we used them as one indicator of the value of sites, as guides to what was changing in terms of woodland management and the woodland environment more generally; some species such as bramble and bracken could also be a problem when we were trying to get regeneration. There was not then the time to pull the different strands together, so when I was back in Oxford I thought I should give it a go.

Have you noticed any unusual changes within woodland flora this Spring following the lockdown? Has it helped or hindered?

I would not really expect to see a direct effect of lockdown on the plants: often their growth is determined by reserves laid down the previous year and a few months is not very long when you consider that many woodland plants – not just the trees – can live for several decades. There could be indirect effects, for example if less disturbance in woods means that deer produce more fawns, so more hungry mouths to nibble away at the flora in future.

Although adaptable, woodlands are clearly not invincible. What do you think is the greatest threat to woodland ecosystems?

In the longer-term (25-50 yrs) climate change. The micro-climate at ground level in a wood has not changed as much as out in the open because of the sheltering effect of the tree layer, but it will do eventually and this will lead to a re-assortment of which species can thrive in different parts of the country.

In the medium term (10-25 years) I suspect that we are going to see more and more evidence of change from the build-up of nitrogen in forest soils from the emissions from cars, modern farming etc. I am picking up signs that this is happening in Wytham.

The immediate threat – and it affects our ability to deal with the medium and longer-term issues as well – comes from the impact of high numbers of deer in the countryside. They limit tree regeneration and make woodland management more difficult as well having direct effects on the ground flora species themselves. At Wytham we saw during the eighties and nineties a complete shift from a flora of herbs and bramble to grass-dominated cover. That is being reversed – we are fortunate in being able to manage the deer population there – but in many other woods deer numbers are too high. This means for example that it will be difficult to get the regeneration of species such as oak, beech or hazel that will be needed over the next few years to fill the gaps in the canopy left as Ash Dieback progresses.

What single policy change would you like to see to help counter this threat?

Through history trees and woods (and hence the woodland flora) have survived best where they are valued by society: so we need to encourage greater use of wood as a material in buildings, as fuel, as a feedstock for industry; as well as promoting woodland as places for recreation, to help with water management, for carbon sequestration, and as a source of inspiration.

As you note in the book, there’s currently a lot of interest in rewilding. What role do you think rewilding can play in the future of UK woodlands?

From the answer to the previous question it will be obvious that I want to see a lot of woods being managed to provide the materials that society needs; moreover many of our woodland plants can thrive under such conditions – if management is done carefully – as they have done for centuries. Rewilding though also has a great role to play in future conservation alongside actively managed woods (as long as we can get away from the endless debates about the meaning of the term itself). Rewilding leads to different types of woodland structures and composition, a different set of dynamics in the landscape, some of which may be analogous to what may have existed 6,000 years ago, but other combinations will be completely new. New mixtures of woodland plants (and animals) will come to be associated with rewilded treescapes that will also be a response to the changed environmental conditions. Exactly what will emerge unpredictable and there will be interesting challenges ahead for land managers, regulators and conservation advisers – we are not in the UK going to be able to be completely ‘hands-off’ even in the wildest of rewilding.

Rewilding is however one of the reasons why I am cautiously optimistic we can yet pass on a reasonable legacy of woodland flowers.

Now that the book is finished, and after a well-earned rest, are there any plans or works-in-progress that you can tell us about?

My first priority has been to try to catch up on writing-up the results from long-term studies of the flora in Wytham Woods and The Warburg Reserve near Henley. Also once the country has opened up a bit more after Covid-19 I plan to spend time to spend some more time with the wood beneath the trees; so I have been drawing up a list of woods across the country that I want to go and visit again.

Woodland Flowers, published by Bloomsbury is out now. We have a very limited amount of signed stock, available while stocks last.

Woodland Flowers: Colourful Past, Uncertain Future

Woodland Flowers: Colourful Past, Uncertain Future

By: Keith J Kirby

Hardback | August 2020| £29.99 £34.99

In this insightful and original account, Keith Kirby explores the woodland plants of Britain.

Woodland Flowers: Colourful Past, Uncertain Future is the eighth instalment of the popular British Wildlife Collection.

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

Some of the most well-known and respected scientists in history have had an incredibly varied range of interests and passions. Take Darwin, for example, who not only studied plants and animals, but also geology, anthropology, taxidermy and medicine. Do you think that, in modern times, we no longer celebrate or respect the ‘generally curious’ and instead expect people to be much more specialist in their areas of expertise?

Some of the most well-known and respected scientists in history have had an incredibly varied range of interests and passions. Take Darwin, for example, who not only studied plants and animals, but also geology, anthropology, taxidermy and medicine. Do you think that, in modern times, we no longer celebrate or respect the ‘generally curious’ and instead expect people to be much more specialist in their areas of expertise?

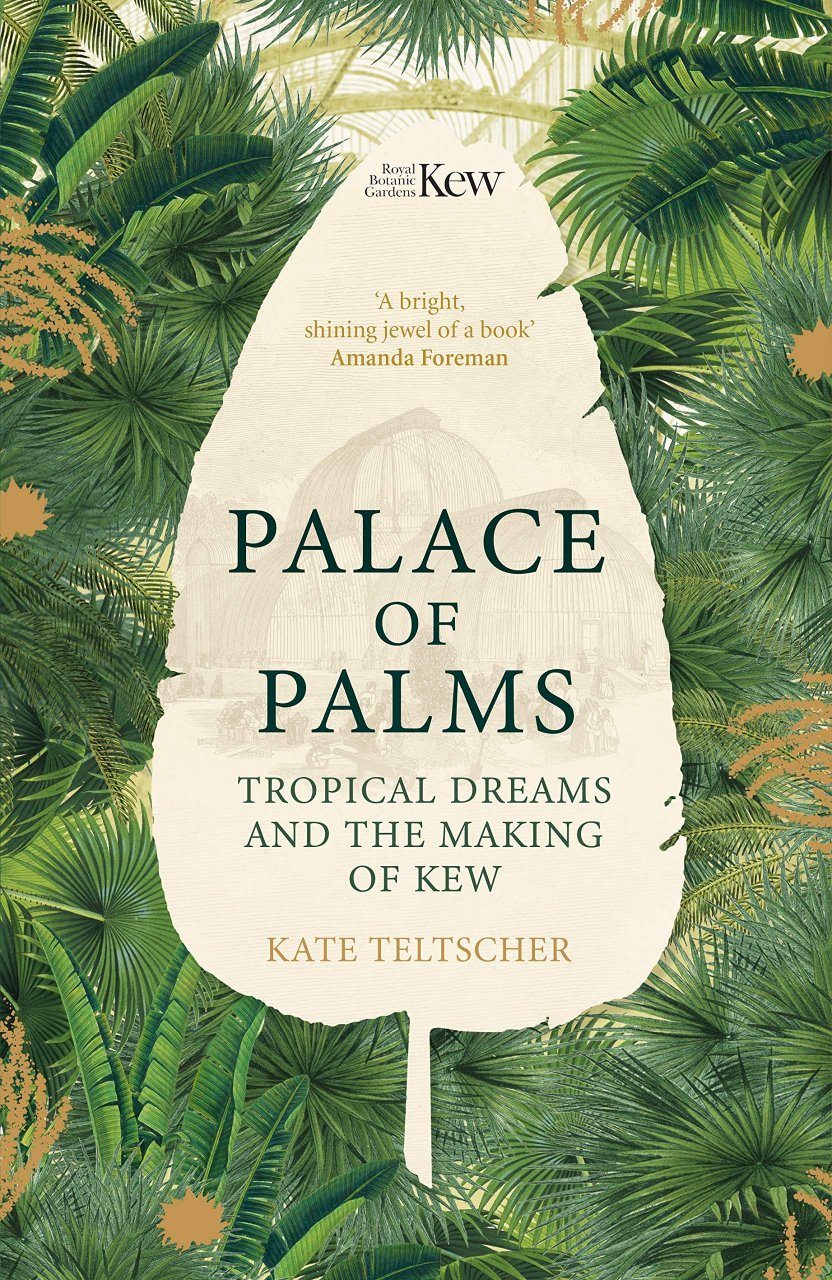

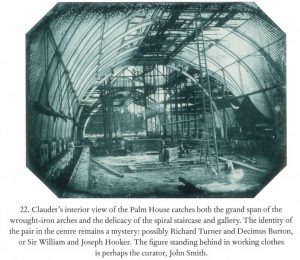

Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today

Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

Why were palms so important to the Victorians?

Why were palms so important to the Victorians? How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?

How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?

Ben Fitch is the national project manager for the

Ben Fitch is the national project manager for the

The Riverfly Partnership coordinates a number of projects looking at lots of different measurements of river health. These include surveying invertebrates, physical habitat, hydromorphological features and pollution events. What happens to the data that is collected in these projects? Who uses it and what for?

The Riverfly Partnership coordinates a number of projects looking at lots of different measurements of river health. These include surveying invertebrates, physical habitat, hydromorphological features and pollution events. What happens to the data that is collected in these projects? Who uses it and what for?

I would also like to share this beautiful image, simply named ‘Mayfly’, photographed by Jon Hawkins. This was the winning entry to the most recent RP Photography Competition and I think it deserves to be seen! (Reproduced with kind permission of the Riverfly Partnership, copyright Jon Hawkins.)

I would also like to share this beautiful image, simply named ‘Mayfly’, photographed by Jon Hawkins. This was the winning entry to the most recent RP Photography Competition and I think it deserves to be seen! (Reproduced with kind permission of the Riverfly Partnership, copyright Jon Hawkins.)

Tim Dee is a naturalist, radio producer, and author of

Tim Dee is a naturalist, radio producer, and author of

By travelling north you poetically write about the birds that come and go; from observing redstarts in Lake Lagano, Ethiopia, to enjoying the dawn chorus in a reedbed in Somerset. What can be learned from birds in migration, and how is migration changing for them?

By travelling north you poetically write about the birds that come and go; from observing redstarts in Lake Lagano, Ethiopia, to enjoying the dawn chorus in a reedbed in Somerset. What can be learned from birds in migration, and how is migration changing for them?

Stephen Moss is a naturalist, broadcaster, television producer and author. He is the

Stephen Moss is a naturalist, broadcaster, television producer and author. He is the

The Wren: A Biography

The Wren: A Biography

Wonderland: A Year of Britain’s Wildlife, Day by Day

Wonderland: A Year of Britain’s Wildlife, Day by Day Wild Hares and Hummingbirds: The Natural History of an English Village

Wild Hares and Hummingbirds: The Natural History of an English Village