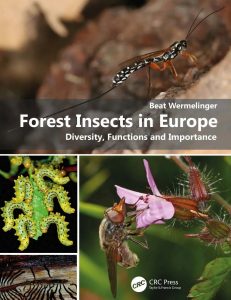

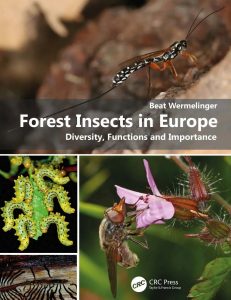

Forest Insects in Europe has been written not only with professional entomologists in mind, but also for nature lovers generally. The descriptions of the various roles insects play in forest ecosystems are intended to be easily comprehensible, but still scientific.

Forest Insects in Europe has been written not only with professional entomologists in mind, but also for nature lovers generally. The descriptions of the various roles insects play in forest ecosystems are intended to be easily comprehensible, but still scientific.

We recently caught up with the book’s author, Beat Wermelinger, who works as a Senior Scientist at the Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL. His research interests include bark beetles and natural enemies, Biodiversity, windthrow succession, climate change and neozoa. Beat answered our questions in German and our bi-lingual team members were excited to translate these to English for us. Discover more below in both languages.

1) Could you tell us a little bit about your background and how you came to write Forest Insects in Europe: Diversity, Functions and Importance?

I have been working at the Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL (Swiss Federal Institute WSL) (a forest research institute) for 30 years and until recently was the head of the entomology group. Simultaneously, I have also been teaching forest insects at the ETH Zurich. During this time, a large pool of knowledge and information has accumulated. I have also been a passionate insect photographer for just as long, which is reflected in an image database of around 16.000 insect photos. These two strands provided an ideal basis for conveying the importance and fascination of insects in one scientifically based book, which was also richly illustrated with photos, for both specialists and all those interested in nature.

Können Sie uns etwas über Ihren Hintergrund erzählen und wie Sie dazu kamen, Forest Insects in Europe: Diversity, Functions and Importance zu schreiben?

Seit 30 Jahren arbeite ich an der Eidgenössischen Forschungsanstalt WSL (Swiss Federal Institute WSL) (einem Waldforschungsinstitut) und leitete dort bis vor kurzem die Gruppe Entomologie. Zugleich unterrichte ich fast gleich lang zu Waldinsekten an der Hochschule ETH in Zürich. In dieser Zeit hat sich ein grosser Fundus an Kenntnissen und Informationen angesammelt. Ausserdem bin ich seit mindestens ebenso langer Zeit ein passionierter Insektenfotograf, was sich in einer Bilddatenbank von rund 16.000 Insektenbildern niedergeschlagen hat. Diese beiden Grundlagen boten eine ideale Basis, die Bedeutung und Faszination von Insekten in einem zwar wissenschaftlich fundierten, aber auch reich mit Fotos illustrierten Buch sowohl Fachpersonen als auch allen Naturinteressierten zu vermitteln.

2) The book tackles a vast array of insect groups and ecological functions – were there any particular challenges in collating so much information in one place?

Much of the information comes from my readings or lectures. However, since I wanted to portray the ecological and economic importance of forest insects as broadly as possible, I still had to review a lot of published material. Above all, I wanted to support quantitative data with accurate citations. Owing to the Internet, such research is easier today than it was 20 years ago… Fortunately, I also had my own photographs on almost all topics.

Much of the information comes from my readings or lectures. However, since I wanted to portray the ecological and economic importance of forest insects as broadly as possible, I still had to review a lot of published material. Above all, I wanted to support quantitative data with accurate citations. Owing to the Internet, such research is easier today than it was 20 years ago… Fortunately, I also had my own photographs on almost all topics.

Das Buch befasst sich mit einer Vielzahl von Insektengruppen und Funktionen – gab es besondere Herausforderungen, so viele Informationen in einem Buch zusammenzufassen?

Ein wesentlicher Teil der Informationen stammt aus meinen Vorlesungen oder Vorträgen. Da ich aber die ökologische und ökonomische Bedeutung von Waldinsekten möglichst breit darstellen wollte, musste ich doch noch Einiges an Literaturarbeit leisten. Vor allem wollte ich quantitative Angaben mit korrekten Literaturzitaten abstützen. Dank dem Internet sind solche Recherchen heute einfacher als noch vor 20 Jahren… Erfreulicherweise hatte ich auch zu fast allen Themen eigene Bilder.

3) Are there any insect groups that hold a particular interest for you?

Professionally, I am mainly concerned with wood-dwelling insects. I am especially interested in the bark beetles, and their natural enemies as well as the intensive interactions with their host trees. Bark beetles are known to be pests, but they are also pioneers in the decay of wood. I also deal with the wood-dwelling longhorn beetles and jewel beetles, which often lend themselves to photography because of their size and beauty. For decades I have dealt with the development of their biodiversity after disruptive events such as storms or fire. The social red wood ants or the galling insects also fascinate me with their ingenious way of life.

Professionally, I am mainly concerned with wood-dwelling insects. I am especially interested in the bark beetles, and their natural enemies as well as the intensive interactions with their host trees. Bark beetles are known to be pests, but they are also pioneers in the decay of wood. I also deal with the wood-dwelling longhorn beetles and jewel beetles, which often lend themselves to photography because of their size and beauty. For decades I have dealt with the development of their biodiversity after disruptive events such as storms or fire. The social red wood ants or the galling insects also fascinate me with their ingenious way of life.

Haben Sie eine Insektengruppe, an der Sie besonders interessiert sind?

Beruflich beschäftige ich mich vor allem mit holzbewohnenden Insekten. Mich interessieren die Borkenkäfer, ihre natürlichen Feinde und die intensiven Wechselwirkungen mit ihren Wirtsbäumen. Borkenkäfer sind zwar als Schädlinge bekannt, sie sind aber auch Pioniere beim Holzabbau. Weiter befasse ich mich mit den holzbewohnenden Bock- und Prachtkäfern (longhorn beetles, jewel beetles), die sich oft ihrer Grösse und Schönheit wegen auch zum Fotografieren anbieten. Über Jahrzehnte habe ich mich mit der Entwicklung ihrer Artenvielfalt nach Störungsereignissen wie Sturm oder Feuer beschäftigt. Auch die staatenbildenden Waldameisen (red wood ants) oder die gallbildenden Insekten (galling insects) faszinieren mich durch ihre ausgeklügelte Lebensweise.

4) In Chapter 18, you discuss the severe and widespread decline of several insect groups. What has caused so many species to dwindle in European forests? And what is being done to address these threats?

There are two main causes for the decline in much of the forest insect fauna. The intensive use of wood in the past centuries has led to the fact that the forest area in Europe has decreased significantly over a long period of time, the trees no longer reach their natural age phase, and there were almost no dead trees that could slowly rot. In the case of many wood-dwelling insects that are dependent on so-called habitat trees or develop in decayed, thick tree trunks, this has led to a severe threat to their biodiversity. In recent decades, the forest area has increased again and in many countries the preservation of old trees and dead wood is being promoted. However, the impact is still modest.

There are two main causes for the decline in much of the forest insect fauna. The intensive use of wood in the past centuries has led to the fact that the forest area in Europe has decreased significantly over a long period of time, the trees no longer reach their natural age phase, and there were almost no dead trees that could slowly rot. In the case of many wood-dwelling insects that are dependent on so-called habitat trees or develop in decayed, thick tree trunks, this has led to a severe threat to their biodiversity. In recent decades, the forest area has increased again and in many countries the preservation of old trees and dead wood is being promoted. However, the impact is still modest.

A second reason is the fact that many shrubs and pioneer tree species such as willow and poplar have disappeared and the forests have often become more monotonous and closed. This mainly affects the forest butterflies. Today, clearings are created on purpose from which not only these insects, but also other light-loving forest species such as certain orchids or birds can benefit.

In Kapitel 18, erwähnen Sie den verbreiteten Rückgang mehrerer Insektengruppen. Was hat den Rückgang so vieler Arten in den europäischen Wäldern verursacht? Und was wird getan, um diese Bedrohungen zu begegnen?

Es gibt hauptsächlich zwei Gründe für den Rückgang eines grossen Teils der Waldinsektenfauna. Die intensive Holznutzung der vergangenen Jahrhunderte hat dazu geführt, dass die Waldfläche in Europa über lange Zeit sehr stark abgenommen hat, die Bäume nicht mehr ihre natürliche Altersphase erreichten, und fast keine abgestorbenen Bäume vorhanden waren, die langsam verrotten konnten. Dies hat bei vielen holzbewohnenden Insekten, die auf sogenannte Habitatbäume angewiesen sind oder sich in toten, dicken Baumstämmen entwickeln, zu einer starken Bedrohung ihrer Artenvielfalt geführt. In den letzten Jahrzehnten hat die Waldfläche zwar wieder zugenommen und in vielen Ländern wird der Erhalt von alten Bäumen und Totholz gefördert. Die Auswirkungen sind jedoch noch bescheiden.

Ein zweiter Grund ist die Tatsache, dass durch die Bewirtschaftung viele Sträucher und Pionierbaumarten wie Weiden oder Pappeln verschwanden und die Wälder oft monotoner und dunkler geworden sind. Dies wirkt sich vor allem auf die Wald-Tagfalter (forest butterflies) aus. Heute werden gezielte Auflichtungen durchgeführt, von denen nicht nur diese Insekten, sondern auch andere lichtliebende Waldarten wie bestimmte Orchideen oder Vögel profitieren.

5) A particular highlight of the book is the wonderful collection of insect photographs, most taken by you. Do you have any advice for people interested in insect photography?

The main problem when photographing small objects is always to be able to focus as much as possible on them. This requires a small aperture and therefore a lot of light. I photograph everything “hand-held” and therefore the shutter speed should be short. For these reasons, I almost always use a ring flash with separately controllable halves and 100 mm macro lens with my SLR camera. Nonetheless, even cameras with a small sensor (even mobile phones!) can nowadays produce surprisingly good images of larger, less volatile insects.

The main problem when photographing small objects is always to be able to focus as much as possible on them. This requires a small aperture and therefore a lot of light. I photograph everything “hand-held” and therefore the shutter speed should be short. For these reasons, I almost always use a ring flash with separately controllable halves and 100 mm macro lens with my SLR camera. Nonetheless, even cameras with a small sensor (even mobile phones!) can nowadays produce surprisingly good images of larger, less volatile insects.

In order to photograph an insect as sharply as possible, you should position yourself so that the insect is parallel to the camera. At least the eyes should always be sharp. Of course, you can also choose a different level of focus for special effects.

In addition to technology, you need an eye for the little things in nature, patience and always a bit of luck! Knowledge of the behavior of certain groups of insects can also come to great advantage.

Ein besonderes Highlight des Buches ist die wunderbare Sammlung von Insektenfotos, die meisten davon von Ihnen aufgenommen. Haben Sie Tipps für Leute, die sich für Insektenfotografie interessieren?

Das Hauptproblem beim Fotografieren von kleinen Objekten ist immer, einen möglichst grossen Teil davon scharf abbilden zu können. Dies erfordert eine kleine Blende und damit auch viel Licht. Ich fotografiere alles “aus der Hand” und deshalb sollte die Verschlusszeit kurz sein. Aus diesen Gründen verwende ich mit meiner Spiegelreflexkamera und dem 100 mm Makroobjektiv fast immer einen Ringblitz mit separat steuerbaren Blitzhälften. Aber auch Kameras mit kleinem Sensor (sogar Handys!) bringen bei grösseren, wenig flüchtigen Insekten heutzutage erstaunlich gute Bilder. Um ein Insekt möglichst scharf abzulichten, sollte man sich so positionieren, dass das Insekt möglichst parallel zur Kamera steht. Mindestens die Augen sollten immer scharf sein. Natürlich kann man die Schärfenebene für spezielle Effekte auch anders wählen.

Zusätzlich zur Technik braucht es aber vor allem das Auge für die kleinen Dinge der Natur, Geduld und immer auch etwas Glück! Auch Kenntnisse des Verhaltens bestimmter Insektengruppen sind von grossem Vorteil.

6) What’s next for you? Do you have any projects that you are currently involved in that you would like to tell us about?

Professionally I am still working for another year, but of course my interest in insects will not vanish when I retire. I would like to use my pictures in other ways and maybe do another book. Above all, not surprisingly I would like to use the time to photograph insects in the great outdoors.

Was kommt als Nächstes für Sie? Haben Sie Projekte, an denen Sie aktuell beteiligt sind und die Sie mit uns teilen können?

Beruflich bin ich noch ein Jahr tätig, aber damit erlischt mein Interesse an Insekten natürlich nicht. Ich würde gerne meine Bilder noch anderweitig in Wert setzen und vielleicht noch ein weiteres Buch in dieser Art machen. Vor allem aber möchte ich die Zeit nutzen, um – wen wundert’s – in der freien Natur Insekten zu fotografieren.

Forest Insects in Europe Diversity, Functions and Importance

Forest Insects in Europe Diversity, Functions and Importance

By: Beat Wermelinger

Paperback | July 2021| £42.99 £49.99

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

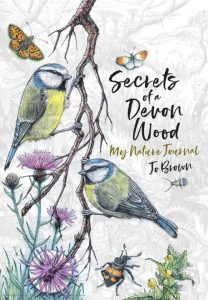

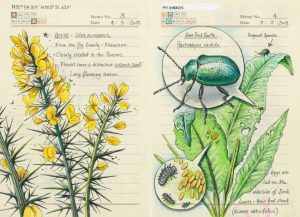

No! I wasn’t even thinking about publishing – the journal was a personal project. I realised very early on that when I draw and document things, I remember them. I remember things like Rumex Obtusifolius (the Latin name for Doc Leaf) – it’s been a wonderful learning tool and almost everything I’ve learned about nature, I’ve learned entirely on my own through observation, supported by research.

No! I wasn’t even thinking about publishing – the journal was a personal project. I realised very early on that when I draw and document things, I remember them. I remember things like Rumex Obtusifolius (the Latin name for Doc Leaf) – it’s been a wonderful learning tool and almost everything I’ve learned about nature, I’ve learned entirely on my own through observation, supported by research.

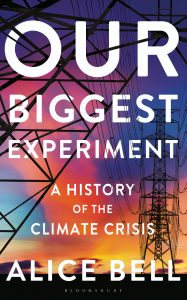

Dr Alice Bell is a journalist and historian of science. Alice was a lecturer in science communication at Imperial College for several years, and was also a key contributor to the International Council for Science’s blog on climate policy in the run-up to the UN Paris talks. Alice has kindly agreed to answer some of our questions below.

Dr Alice Bell is a journalist and historian of science. Alice was a lecturer in science communication at Imperial College for several years, and was also a key contributor to the International Council for Science’s blog on climate policy in the run-up to the UN Paris talks. Alice has kindly agreed to answer some of our questions below.

In his latest book,

In his latest book,  shapes, forms and colours of the birds. They were so very different to the birds I was used to seeing in the Somerset countryside around our home. After that, every now and again I’d see footage of hummingbirds on wildlife documentaries, and began to appreciate further just how remarkable they were – what Tim Dee described as ‘strange birds: not quite birds or somehow more than birds, birds 2.0, perhaps’.

shapes, forms and colours of the birds. They were so very different to the birds I was used to seeing in the Somerset countryside around our home. After that, every now and again I’d see footage of hummingbirds on wildlife documentaries, and began to appreciate further just how remarkable they were – what Tim Dee described as ‘strange birds: not quite birds or somehow more than birds, birds 2.0, perhaps’. There were plenty of other moments that I’ll hold in my heart, and they don’t all involve the iconic, rare species. One such was watching Golden-tailed Sapphires, a hummingbird that looks as if it’s been dipped in rainbows, feeding in a clearing in the immediate aftermath of a heavy rain shower. As the sun broke through the dripping vegetation and steaming air we were suddenly surrounded by myriad small rainbows through which the birds were flying. That moment was ephemeral, over almost as soon as it began, but it’s etched in my memory forever.

There were plenty of other moments that I’ll hold in my heart, and they don’t all involve the iconic, rare species. One such was watching Golden-tailed Sapphires, a hummingbird that looks as if it’s been dipped in rainbows, feeding in a clearing in the immediate aftermath of a heavy rain shower. As the sun broke through the dripping vegetation and steaming air we were suddenly surrounded by myriad small rainbows through which the birds were flying. That moment was ephemeral, over almost as soon as it began, but it’s etched in my memory forever.  I found myself asking myself that very question as my journey into their world unfolded… Hummingbirds certainly seem to touch something deep inside us. They featured in the mythology of the Aztecs; inspired the most dramatic of all of the immense geoglyphs carved into the desert floor by the Nazca; appear in renowned art and literature; and, to this day, are singled out for particular love by those whose gardens they frequent, people who would not necessarily identify themselves as birders.

I found myself asking myself that very question as my journey into their world unfolded… Hummingbirds certainly seem to touch something deep inside us. They featured in the mythology of the Aztecs; inspired the most dramatic of all of the immense geoglyphs carved into the desert floor by the Nazca; appear in renowned art and literature; and, to this day, are singled out for particular love by those whose gardens they frequent, people who would not necessarily identify themselves as birders. Inevitably there were some logistical challenges to contend with, not least having to reacquaint myself with horse-riding after a decades-long and deliberate avoidance of it! There were a couple of close encounters with large predators that were, in hindsight, more alarming than they felt at the time – as a naturalist, I was thrilled to get (very) close views of a puma… But perhaps the most challenging moment of all was landing in Bolivia at the very moment the country was taking to the streets to protest the outcome of a recent presidential election. There was an incident at a roadblock manned by armed men that was genuinely scary, with an outcome that hung in the balance for a terrifying instant, and could easily have ended badly.

Inevitably there were some logistical challenges to contend with, not least having to reacquaint myself with horse-riding after a decades-long and deliberate avoidance of it! There were a couple of close encounters with large predators that were, in hindsight, more alarming than they felt at the time – as a naturalist, I was thrilled to get (very) close views of a puma… But perhaps the most challenging moment of all was landing in Bolivia at the very moment the country was taking to the streets to protest the outcome of a recent presidential election. There was an incident at a roadblock manned by armed men that was genuinely scary, with an outcome that hung in the balance for a terrifying instant, and could easily have ended badly. I sometimes think there’s almost too much optimism expressed when talking about conservation challenges anywhere in the world – a narrative that suggests “if we only care enough, the [insert iconic species name here] can be saved”. And to a degree, that’s good – we’ve got to have hope, as the alternative is too dreadful to countenance – but given our impact to date, and in an uncertain future where the effects of climate change are still unfolding and will continue for many decades to come, to name just the biggest of the mounting pressures on the natural world, I’m not sure that I do feel terribly optimistic, least of all for those hummingbird species that have very localized populations, or depend upon very specific habitats. They’re undeniably vulnerable. But like Fox Mulder,

I sometimes think there’s almost too much optimism expressed when talking about conservation challenges anywhere in the world – a narrative that suggests “if we only care enough, the [insert iconic species name here] can be saved”. And to a degree, that’s good – we’ve got to have hope, as the alternative is too dreadful to countenance – but given our impact to date, and in an uncertain future where the effects of climate change are still unfolding and will continue for many decades to come, to name just the biggest of the mounting pressures on the natural world, I’m not sure that I do feel terribly optimistic, least of all for those hummingbird species that have very localized populations, or depend upon very specific habitats. They’re undeniably vulnerable. But like Fox Mulder,

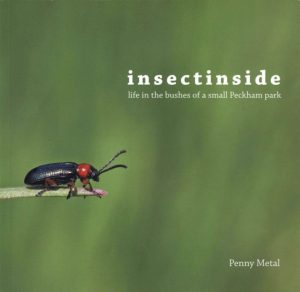

As recently featured on

As recently featured on  photographing and surveying insects. I learned about the insects, watched them and counted the sheer number of species, and realised that no one else had actually surveyed a small urban park extensively. The book came about as I wanted to show people what was living in the bushes and to put Peckham on the entomological map!

photographing and surveying insects. I learned about the insects, watched them and counted the sheer number of species, and realised that no one else had actually surveyed a small urban park extensively. The book came about as I wanted to show people what was living in the bushes and to put Peckham on the entomological map!

and usually open 24 hours – but there is no reason why we can’t include habitats for our wildlife. A simple solution would be to leave areas un-mowed to grow wild. In the parks of my local area in London, large swathes of grasses and flowers have been left to mature and people have been really receptive to it. I think we are finally moving away from the Victorian ideal of neat and tidy!

and usually open 24 hours – but there is no reason why we can’t include habitats for our wildlife. A simple solution would be to leave areas un-mowed to grow wild. In the parks of my local area in London, large swathes of grasses and flowers have been left to mature and people have been really receptive to it. I think we are finally moving away from the Victorian ideal of neat and tidy!

For nearly thirty years now I have been going to stay in a small house at the head of a bay on the west coast of Scotland. It is somewhere my wife’s family have been going for generations and now our children and grandchildren love it too. It has everything you might long for from a place like that: cliffs, woods, waterfalls, a dark beach made of basalt sands, a lighthouse, a ruined castle, stories, beauty, birds, fish; but one thing it did not have because of the geology, was a rockpool. For years I have dreamed of making one – a place of stillness set in the tide, and this book is the story of how I made three of them in different parts of the bay; one dug in with a pickaxe; one made by damming a narrow exit to the sea from a hollow so that the dam held the pool behind it; and one by making a circular wall low down in the intertidal.

For nearly thirty years now I have been going to stay in a small house at the head of a bay on the west coast of Scotland. It is somewhere my wife’s family have been going for generations and now our children and grandchildren love it too. It has everything you might long for from a place like that: cliffs, woods, waterfalls, a dark beach made of basalt sands, a lighthouse, a ruined castle, stories, beauty, birds, fish; but one thing it did not have because of the geology, was a rockpool. For years I have dreamed of making one – a place of stillness set in the tide, and this book is the story of how I made three of them in different parts of the bay; one dug in with a pickaxe; one made by damming a narrow exit to the sea from a hollow so that the dam held the pool behind it; and one by making a circular wall low down in the intertidal.

And so that provided the model – see what was there and look carefully at it. Of course, books like mine are entirely parasitic on the work of many generations of biologists and that too turned out to be the pattern. Watch the sand hoppers and then read about them. Read about them and see how much of what I read I could find on the shore. With prawns, winkles, shore crabs, anemones, limpets, sea-stars, urchins and barnacles, I simply oscillated between the pools and my books: what was there? What had people discovered about them? How did they interact? What were the principles governing their presence or absence? And with all of that came the repeated and slightly sobering realisation that unless I knew to look for something it was very difficult to see it was there. Mysteriously, we are often blind to what is in front of our eyes.

And so that provided the model – see what was there and look carefully at it. Of course, books like mine are entirely parasitic on the work of many generations of biologists and that too turned out to be the pattern. Watch the sand hoppers and then read about them. Read about them and see how much of what I read I could find on the shore. With prawns, winkles, shore crabs, anemones, limpets, sea-stars, urchins and barnacles, I simply oscillated between the pools and my books: what was there? What had people discovered about them? How did they interact? What were the principles governing their presence or absence? And with all of that came the repeated and slightly sobering realisation that unless I knew to look for something it was very difficult to see it was there. Mysteriously, we are often blind to what is in front of our eyes. stages, can recognise the movements and timings of the tides. That sea anemones can identify other sea anemones that are not their relations and effectively destroy them. That prawns have an imagination – that might sound like too much, but it has been shown that they can remember past pain and project it into present and future anxieties. Anxiety is different from fear; it is a fear of what might be there. In other words a prawn can think beyond its present reality.

stages, can recognise the movements and timings of the tides. That sea anemones can identify other sea anemones that are not their relations and effectively destroy them. That prawns have an imagination – that might sound like too much, but it has been shown that they can remember past pain and project it into present and future anxieties. Anxiety is different from fear; it is a fear of what might be there. In other words a prawn can think beyond its present reality. garden whose walls are dissolved twice a day, an enclosure that becomes part of the general world with every high tide. That ambiguity is what entranced me, the sense of its being a micro-ocean, a micro-arcadia, a micro-laboratory in which all kinds of intimacies and precision in natural beings can be witnessed an inch beneath your nose.

garden whose walls are dissolved twice a day, an enclosure that becomes part of the general world with every high tide. That ambiguity is what entranced me, the sense of its being a micro-ocean, a micro-arcadia, a micro-laboratory in which all kinds of intimacies and precision in natural beings can be witnessed an inch beneath your nose.

The

The

And most importantly – just go out there and watch mammals. I may be biased, but for me there is nothing better than being out in the countryside early on a spring morning watching the hares chasing around and knocking seven bells out of each other. You might like to stay up late watching badgers or bats, or enjoy the crazy antics of a squirrel on a bird feeder. It’s important that we engage with nature and encourage our children to do the same. If we don’t see and understand wildlife, we won’t fight for it. And, trust me, we need to fight for it.

And most importantly – just go out there and watch mammals. I may be biased, but for me there is nothing better than being out in the countryside early on a spring morning watching the hares chasing around and knocking seven bells out of each other. You might like to stay up late watching badgers or bats, or enjoy the crazy antics of a squirrel on a bird feeder. It’s important that we engage with nature and encourage our children to do the same. If we don’t see and understand wildlife, we won’t fight for it. And, trust me, we need to fight for it.

slow I would be overtaken by very old people on Zimmer frames. It seemed as though I’d hit 97 five decades prematurely.

slow I would be overtaken by very old people on Zimmer frames. It seemed as though I’d hit 97 five decades prematurely.