Members of the fungal kingdom come in a remarkably diverse variety of shapes, sizes and colours. This blog provides an introduction to several captivating and commonly encountered fungal genera, highlighting their key characteristics, applications and identification tips.

We hope that this guide serves as a useful starting point to help recognise a few of the broad groups of mushrooms commonly encountered in the UK, but it should not be used for foraging purposes. There are around 15,000 species of fungi in Britain and identification can be extremely challenging, often requiring microscopic examination. Even in popular edible groups there are species or lookalikes that can cause serious illness, so it is vitally important to never collect or consume mushrooms unless you are absolutely certain of the identification.

Amanita

There are around 600 species in the Amanita genus across the globe. This fascinating group exhibit great diversity but are best known for Fly Agarics and their distinctive crimson cap which features in mythology, folklore, art and media. While some members of this genus are edible, Amanitas are better known for their poisonous qualities and hallucinogenic properties. There are roughly fifty Amanita species that can be found within the UK. Around fifteen species are common and can be readily found near the base of trees, and five of these individuals are considered poisonous. Despite containing some edible species, the genus is generally avoided and are not considered safe for the novice forager.

Key Characteristics: Amanita’s form a mycorrhizal symbiotic relationship with trees – where they release enzymes and other organic acids to break down organic matter, making the nutrition in the soil more bioavailable. In turn, trees will provide Amanitas with nutrition synthesised through photosynthesis. These mushrooms can be characterised by white (or off-white) gills, that are closely spaced and free from the stipe and they are often seen with irregular patches, or ‘warts’ on the cap, which are fragments of the veil – a membrane that enclosed the young mushroom.

Uses or Applications: Research has shown potential for Aminata species in healthcare, particularly for their anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties. Historically, Fly Agarics have also been used as an insecticide, where they were broken up into milk and used to trap flies.

Species Examples: Death Cap (Amanita phalloides), Destroying Angel (Amanita virosa), Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria), Panther Cap (Amanita pantherina)

Mycena

Introduction: More than 100 Mycena species can be found throughout Britain and Ireland, although less than half of these are considered common or widespread in distribution. They are often referred to as ‘bonnets’ and consist of small, delicate toadstools with fragile stems and a number of these species are known to be bioluminescent, caused by a chemical reaction within the tissue cells.

Key Characteristics: A small conical or bell-shaped mushroom with a thin stem. Mycena caps can be translucent or may have light striations and on the underside, gills are attached to the stipe and produce white spores. Due to their small size (caps from 0.5 – 15cm), some species may only be identified through microscopic examination and spore sampling.

Uses or Applications: Due to their small size, Mycena are not considered edible – some species within the genus are poisonous, and since the group are difficult to identify, they are generally regarded as unsuitable for foraging.

Species Examples: Common Bonnet (Mycena galericulata), Rosy Bonnet (Mycena rosea), Lilac Bonnet (Mycena pura)

Psilocybes

Introduction: The Psyilocybe genus is a widespread group of mushrooms, some of which are well known for their psychoactive properties. They are found across the globe in a range of nutrient rich habitats, and can be found growing in clusters in mossy, grassy or forested areas in the UK. The genus is split into two clades, one of which is comprised of hallucinogenic species that have a blue staining reaction when bruised (however it is worth noting that not all blue-staining fungal species contain psilocybin).

Key Characteristics: Psilocybes fall into the ‘little brown mushroom’ category – a non-descript, brown to yellow coloured mushroom that is small to medium in size. These gilled toadstools typically produce a dark spore print, have a slender stipe and a hygrophanous cap that changes colour as moisture levels change in the mushroom tissue.

Uses or Applications: Psilocybes are often referred to as ‘magic mushrooms’ for their psychoactive properties. Species in this genus can contain compounds such as psilocybin, which induce hallucination and changes in perception for those who have ingested the compound and has been historically used to treat some psychiatric conditions.

Species Examples: Liberty Cap (Psilocybe semilanceata), Wavy Cap (Psilocybe cyanescens).

Lycoperdon

Introduction: A genus of puffball mushrooms with approximately fifty species across the globe. These instantly recognisable fungi are common and widespread around the UK and can be found on the ground in woodland and pasture with plenty of leaf litter, where they decompose organic matter.

Key Characteristics: Lycoperdon species have a distinctive set of characteristics that allow for easy identification. These small-medium sized balls do not have gills or spores and have no cap. They tend not to have a stipe, but some species do have a small one that can appear thicker. Some species have a tough outer skin, and inside, the mushroom should have white, spongy flesh that turns yellow or brown as the spores mature. Members of this genus are basidiomycetes – they produce spores within the basidia (a microscopic spore-producing structure) which are located inside the fruiting body, releasing a cloud of spores when squeezed.

Uses or Applications: Most species in the Lycoperdon genus are edible. They are said to have a mild taste and smell, making them choice edibles for many foragers. Although they have a tendency to become slimy once cooked, puffballs are a common substitute in various vegetarian dishes.

Historically, puffballs have been used in medicine for their hemostatic properties which stop or slow the flow of blood, and blacksmiths in particular are known to have kept puffballs in the forge for these properties, as well as their ability to aid in the healing of burns.

Species Examples: Common Puffball (Lycoperdon perlatum), Pestle Puffball (Lycoperdon excipuliforme), Stump Puffball (Lycoperdon pyriforme)

Boletus

Introduction: There are around 250 Boletus species worldwide, which until recently, were divided into smaller families and have since combined to form a larger genus. There are approximately 80 species of Bolete within the family Boletaceae in the UK, and many of these are choice edible species for foragers. As a largely mycorrhizal group, Boletes are commonly found in woodland or forest but may also be found in grassland habitats. Boletes can be found in a variety of shapes, sizes and colours –appearing quite large with thick, meaty fruiting bodies or smaller in size with more delicate features. Species in this group are basidiomycetes – instead of gills, these mushrooms have spongy, pore-filled masses on the underside of the cap which release spores.

Key Characteristics: Boletes are usually large, fleshy mushrooms with a thick stipe, characterised by spore-bearing structures on the underside of the cap, called tubes. The group is basidiomycetes, which feature a spongy mass containing pores that disperse white to yellow spores into the air. A large number of Boletes are also known to form mycorrhizal relationships with trees, and can often be found under broadleaf and coniferous trees.

Uses or Applications: A number of Bolete species are edible, including the King Bolete, and are considered some of the most versatile edible fungi.

Species Examples: King/Cep/Porcini/Penny Bun Bolete (Boletus edulis), Summer Bolete (Boletus reticulatus), Bronze Bolete (Boletus aereus)

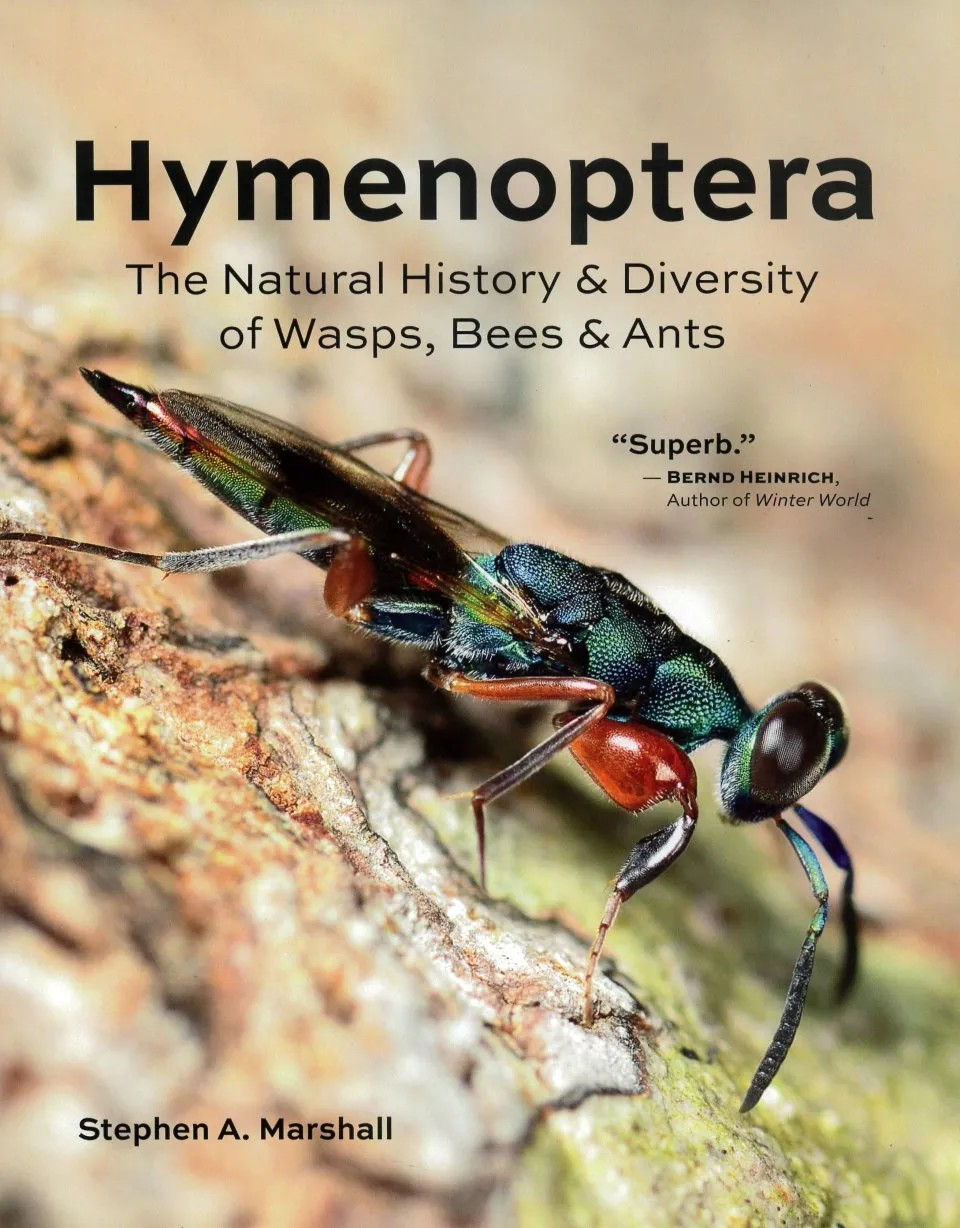

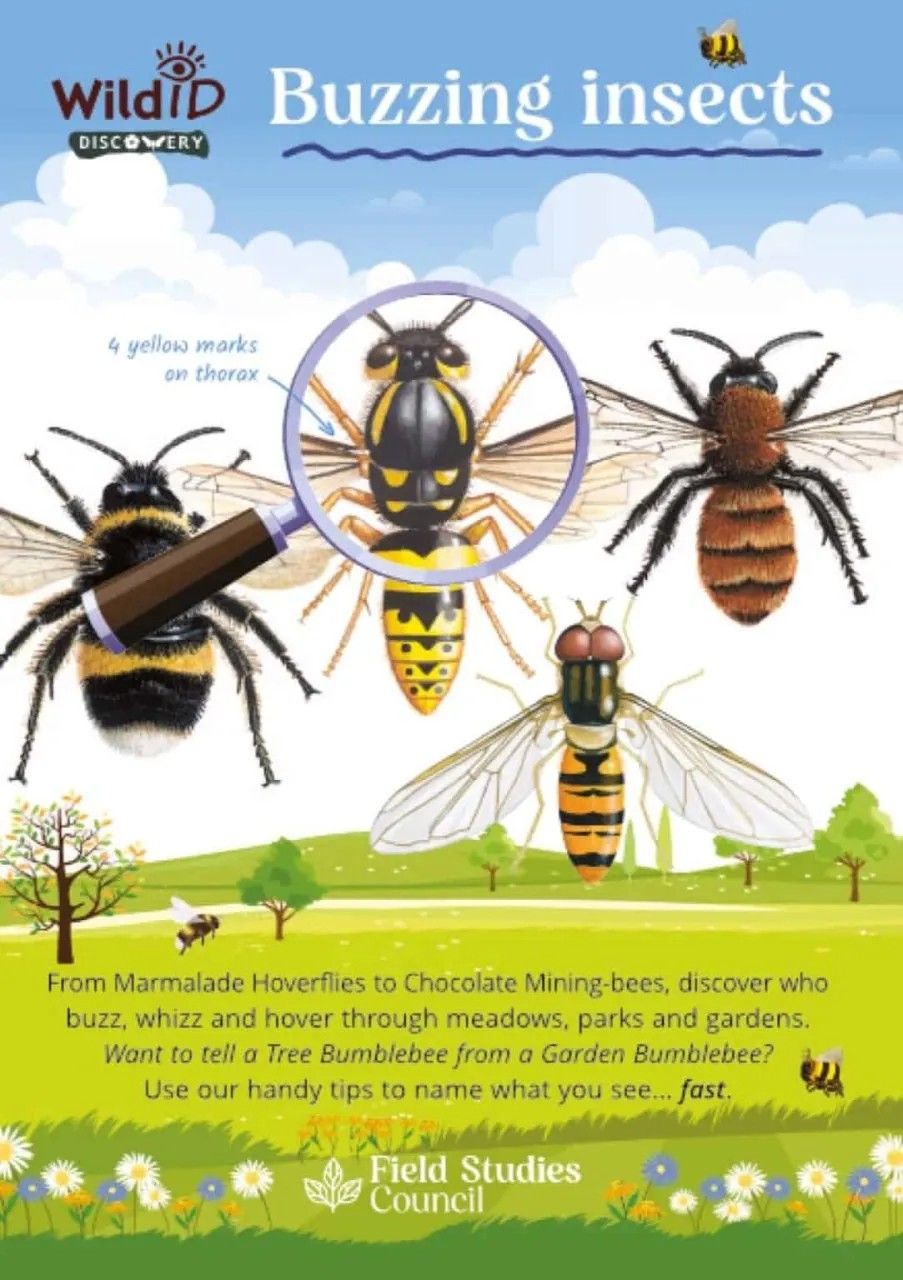

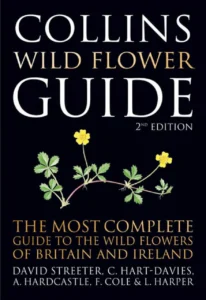

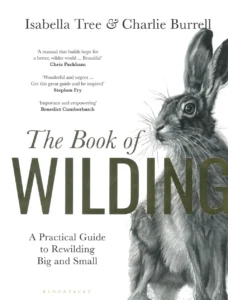

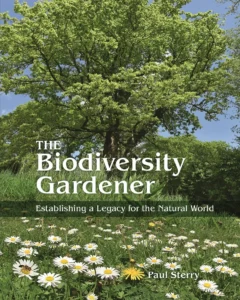

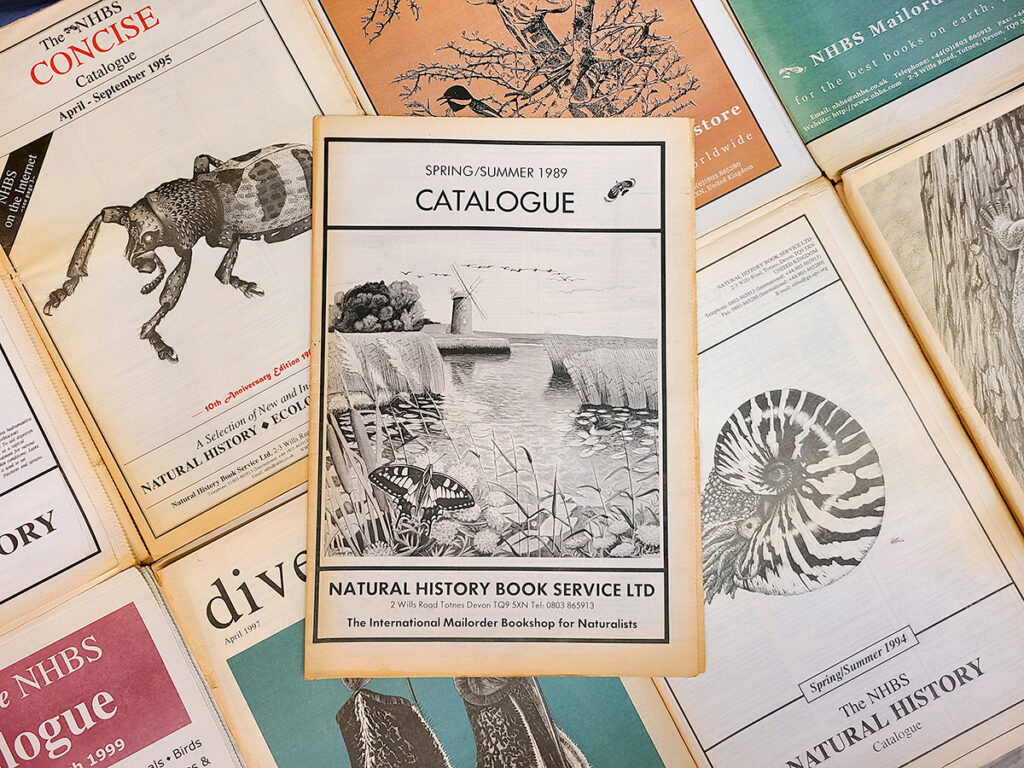

If you’d like to delve deeper into the world of fungi and attempt to identify the mushrooms species you come across, here are our top picks to get you started: