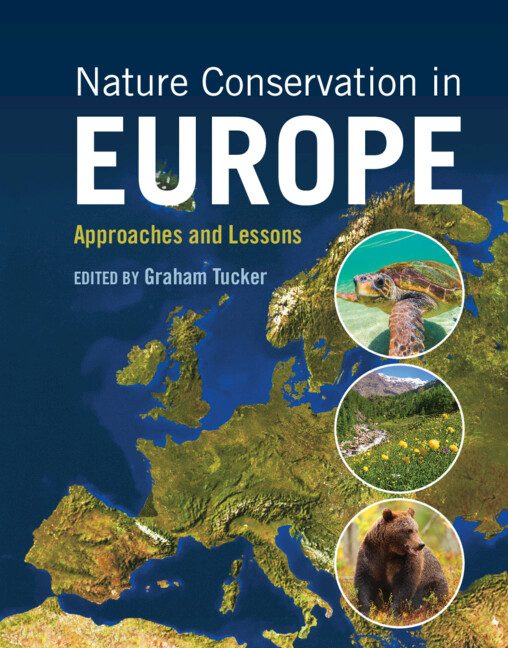

This informative and wide-ranging book examines the nature conservation responses of the UK and twenty-five EU Member States, analysing their achievements and failures and providing notable case studies from which comparisons and lessons can be obtained. Covering topics such as biodiversity pressure, legislation and governance, biodiversity strategies, species protection, protected areas, habitat management and funding, the book provides an incredibly in-depth appraisal of our management of European ecosystems and species and how this has contributed to the current concerning state of nature in these regions.

This informative and wide-ranging book examines the nature conservation responses of the UK and twenty-five EU Member States, analysing their achievements and failures and providing notable case studies from which comparisons and lessons can be obtained. Covering topics such as biodiversity pressure, legislation and governance, biodiversity strategies, species protection, protected areas, habitat management and funding, the book provides an incredibly in-depth appraisal of our management of European ecosystems and species and how this has contributed to the current concerning state of nature in these regions.

Editor Graham Tucker is an ecologist and a leading authority on European nature conservation policy, with a particular interest in its achievements and failures. He currently works as an independent consultant and proprietor of Nature Conservation Consulting. Prior to this he worked for Birdlife International and as Head of the Biodiversity Programme for the Institute for European Environmental Policy.

Editor Graham Tucker is an ecologist and a leading authority on European nature conservation policy, with a particular interest in its achievements and failures. He currently works as an independent consultant and proprietor of Nature Conservation Consulting. Prior to this he worked for Birdlife International and as Head of the Biodiversity Programme for the Institute for European Environmental Policy.

We recently chatted with Graham about the book and about the necessity for international co-operation in conservation, the importance of funding, stakeholder engagement and societal support in the creation and maintenance of protected areas, plus his plans for the future.

This is an impressive endeavour into covering the enormous topic of conservation across Europe. What inspired you to create this book?

Several things drove me to prepare the book. Firstly, like many others, I am concerned by the ongoing decline in many species and degradation of habitats in Europe, and that nature conservation has not been able to halt, let alone reverse most losses. Whilst there have been successes for some species, they have been insufficient, and consequently biodiversity targets have been repeatedly missed. Secondly, having had the privilege to work over the last few decades with many nature conservation experts across Europe, I realised the reasons for these failures varied between countries. Whilst the broad approaches to nature conservation have been similar, there have been significant differences, especially in their implementation and outcomes. Comparing national experiences could therefore provide valuable lessons in terms of which nature conservation measures have, and have not worked, and why. However, nature conservationists have tended to mainly draw lessons from national experiences, in part because of language barriers and the other difficulties with finding relevant key information.

Therefore, there seemed to be a need for a book that describes and critically examines the nature conservation objectives and actions that have been taken in Europe, primarily through individual country chapters written by national experts with a deep knowledge of what has really happened. Having discussed the idea with some nature conservationists I found that there was considerable enthusiasm for the book and many willing to contribute, despite the huge amount of work it would involve. This was also inspiring and persuaded me to go ahead as its preparation has depended on the hard work, generosity and patience of many people; of which I am especially indebted to the 52 co-authors.

Chapter 3 discusses the international drivers of nature conservation and their impacts on policies in Europe. How important is international co-operation and coherency in policy to nature conservation? Do you think there is enough large-scale international conservation?

International cooperation and coherence are vital for effective nature conservation. This is most obviously the case for migratory species, as well as rivers, seas and ecosystems that cross national borders, and transboundary protected areas. This has been widely recognised, so there is now a reasonably complete nature conservation framework in Europe, including the global UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern Convention) and, of most influence, the legally binding EU Birds and Habitats Directives. These agreements have aided cooperation such as through sharing programmes of work, knowledge and funding. Most importantly, they have helped raise ambitions by creating a level playing field – which gives countries the confidence to act, knowing that they would not be alone.

Unfortunately, the UK’s departure from the EU has undermined this cooperation and alignment, resulting in potential divergence in ambitions, policies and legislation, both between the UK and EU and between the UK nations. So far there has been little divergence in UK practices and standards are being maintained. But this could change with time, especially in England as a result of the Retained EU Law Bill.

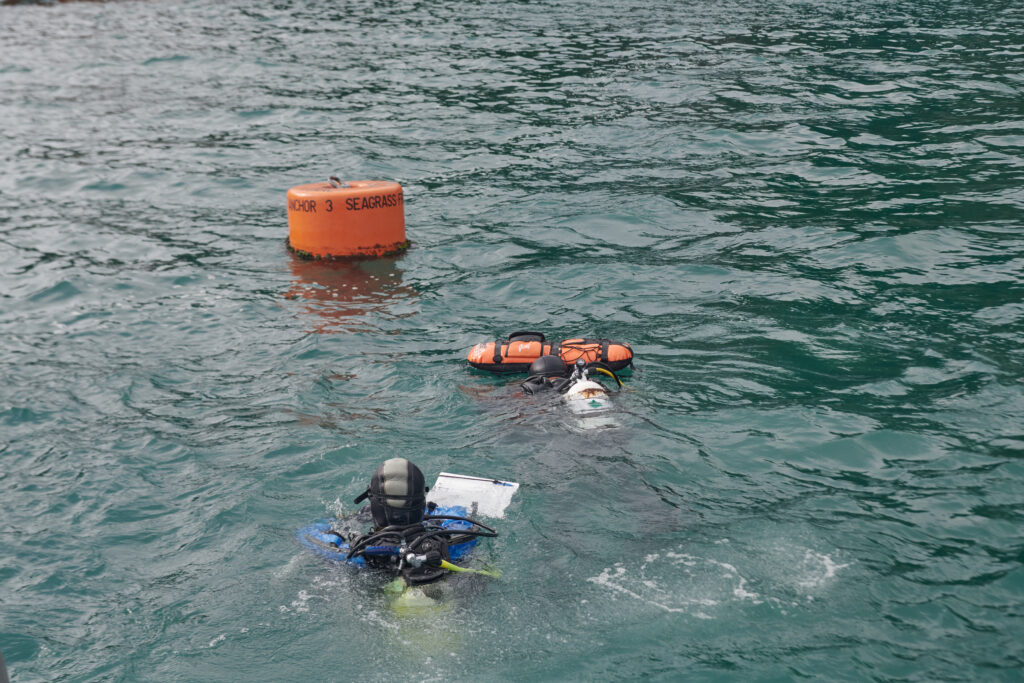

Chapter 5, ‘Conclusions, Lessons Learnt and Implications for the Future’, mentions that, while nature conservation has likely slowed the rate of decline, many habitats such as wetlands and semi-natural grasslands forests have continued to be lost or degraded. Do you think large-scale commitments such as the one to increase the UK’s and EU’s protected area network to 30% of both land and sea by 2030 will generate the right amount of funding, stakeholder engagement and societal support to create effective, large-scale conservation?

I am sure there is wide public support for the improvement and expansion of the protected area network, both on land and sea, in the UK and elsewhere in Europe. This is because the potential nature and wider related social and economic benefits of protected areas are increasingly appreciated. However, in most countries it is more important to improve the effectiveness of the existing network, in particular with stronger nature conservation objectives and better practical management. This requires more funding and stronger regulation, which I am doubtful that most governments are currently committed to.

This chapter also mentions that nature conservation is dependent on enforced legislation, funding and motivated people. Which do you believe is the hardest to obtain and therefore is the biggest threat to current and future conservation efforts?

All three are needed, and they are to some extent interrelated and dependent upon each other. However, the lack of funding, which is in part due to insufficiently motivated politicians, is currently the main constraint in most countries. This hampers the enforcement of legislation, as well as limiting practical nature conservation and restoration actions in protected areas and the wider environment.

Whilst public support for nature conservation is substantial in many countries, especially the UK, it varies greatly. Political support also tends to lag behind public support, in part due to the influence of powerful lobbying groups. Wider and deeper societal engagement is therefore essential to stimulate stronger political support, funding and regulations. It is therefore encouraging that support for nature conservation is growing. This is needed now to counter recent calls from some politicians in the UK and EU to weaken some environmental ambitions and slow down actions.

What impact do you hope that this book will have?

I hope that the book will clearly show that nature conservation works when it is properly implemented – such that it can halt biodiversity declines and even restore ecosystems. Therefore, the ongoing biodiversity crisis is not because we are doing the wrong thing. On the contrary, we need to massively scale up what we are doing already. As said, we know what we need: strong and enforced regulations, more and better targeted funding, and more deeply motivated people to call for and help conserve nature. We should still seek to improve the effectiveness of nature conservation measures, basing policy and practical decisions on evidence, but be wary of calls for radical changes in approach.

Of all the countries discussed within this book, which do you believe are leading the way in nature conservation?

Unfortunately, this is not easy to answer as it is often difficult to reliably compare data across the countries. For example, some countries have large protected area networks (e.g. Croatia, Slovakia and Slovenia) in contrast to others (e.g. Belgium, Finland, Ireland and Sweden). However, the statistics are not always reliable as some countries, such as Bulgaria, Denmark and UK include areas that do not meet internationally recognised protected area definitions. Furthermore, the effectiveness of protected area network is not necessarily closely related to their size, but more their conservation objectives and the effectiveness of their practical management. Similarly, comparing the adequacy of funding is difficult because needs vary and it is not always clear how much goes towards species and habitat conservation priorities, and what it actually achieves.

As described in some detail in the conclusion chapter, all countries have both strengths and weaknesses, so it is difficult to identify overall leaders. As regards the UK, we have been leaders in some respects in particular in relation to science and the strong role of NGOs, and producing a wealth of strategies, including the first Biodiversity Action Plan in the world in response to the CBD. However, the UK has underperformed overall, primarily due to poor implementation of its strategies and other initiatives, largely as a result of limited political support and therefore weak regulations and inadequate funding.

Do you have any future plans that you’re able to share with us?

As the book has taken over five years to prepare, I am having a bit of a break from writing for the moment. But I am continuing to work on EU and UK nature conservation issues, especially in relation to climate change.

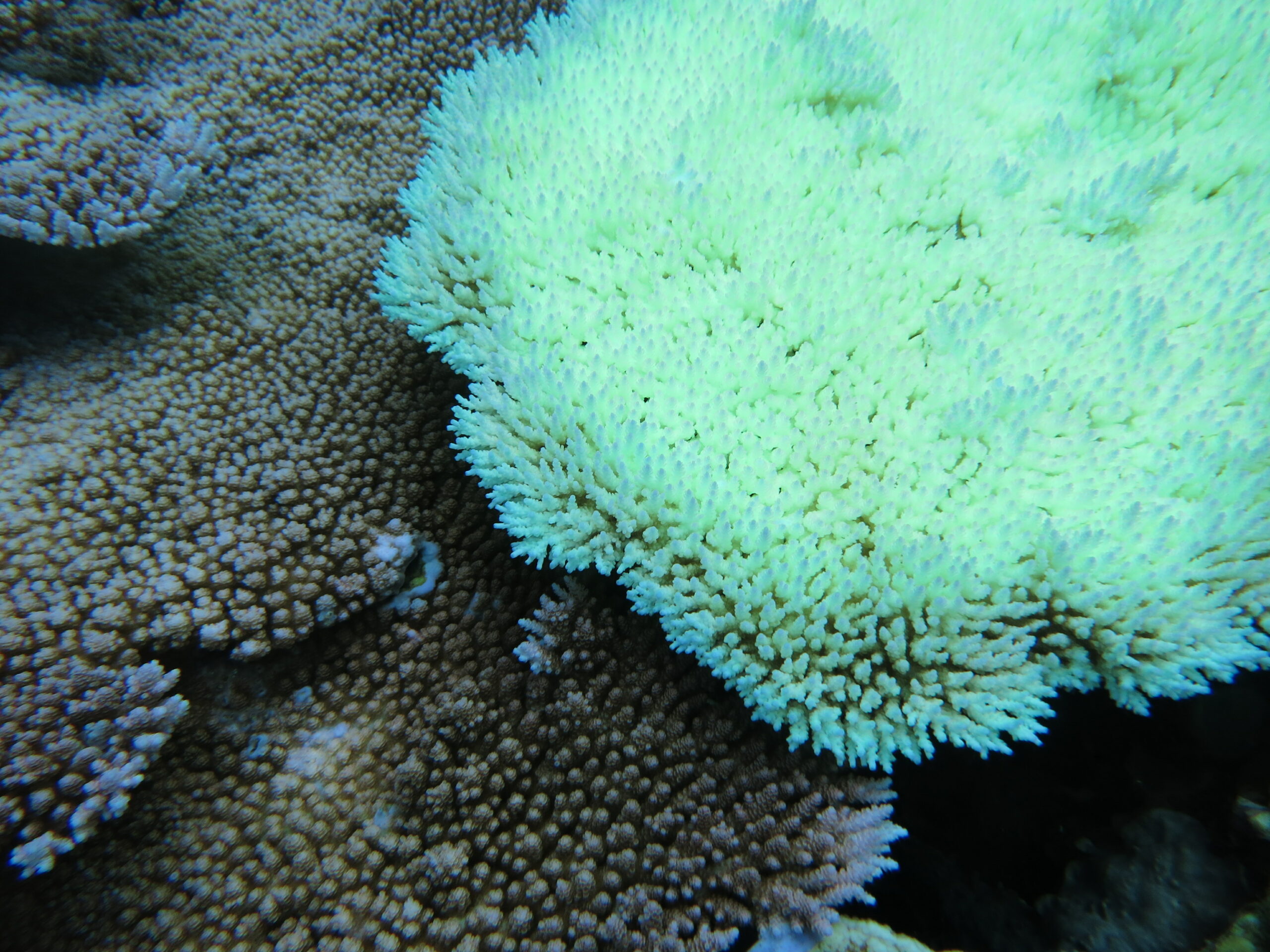

The impacts of climate change on nature are of growing concern to me, as I think they will be much worse than many people realise. In addition to the increasing disruption to ecosystems, there is the likelihood of huge impacts from climate change mitigation measures and adaptation actions over the next 30 years. Whilst it is essential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, many proposed responses can be highly damaging for nature, including widescale inappropriate afforestation, use of bioenergy, solar farms and hydro-energy. Damaging climate change adaptation measures are also likely to increase, such as increased water abstraction from wetlands, as is already affecting the Coto Donana in Spain. At the same time, well designed ecosystem-based measures can contribute substantially to mitigation and adaptation, whilst being beneficial for nature – but these are being underused. Maybe, in time, I will prepare a book on this.

Nature Conservation in Europe: Approaches and Lessons was published in May 2023 by Cambridge University Press and is available from nhbs.com

This informative and wide-ranging book examines the nature conservation responses of the UK and twenty-five EU Member States, analysing their achievements and failures and providing notable case studies from which comparisons and lessons can be obtained. Covering topics such as biodiversity pressure, legislation and governance, biodiversity strategies, species protection, protected areas, habitat management and funding, the book provides an incredibly in-depth appraisal of our management of European ecosystems and species and how this has contributed to the current concerning state of nature in these regions.

This informative and wide-ranging book examines the nature conservation responses of the UK and twenty-five EU Member States, analysing their achievements and failures and providing notable case studies from which comparisons and lessons can be obtained. Covering topics such as biodiversity pressure, legislation and governance, biodiversity strategies, species protection, protected areas, habitat management and funding, the book provides an incredibly in-depth appraisal of our management of European ecosystems and species and how this has contributed to the current concerning state of nature in these regions.

The 4th edition of Bat Surveys for Professional Ecologists: Good Practice Guidelines is the latest update of the Bat Conservation Trust (BCT) Guidelines and features new content on biosecurity, night-vision aids, tree surveys and auto-identification for bat sound analysis. Several key chapters have been expanded, and new tools, techniques and recommendations included. It is a key resource for professional ecologists carrying out surveys for development and planning.

The 4th edition of Bat Surveys for Professional Ecologists: Good Practice Guidelines is the latest update of the Bat Conservation Trust (BCT) Guidelines and features new content on biosecurity, night-vision aids, tree surveys and auto-identification for bat sound analysis. Several key chapters have been expanded, and new tools, techniques and recommendations included. It is a key resource for professional ecologists carrying out surveys for development and planning.