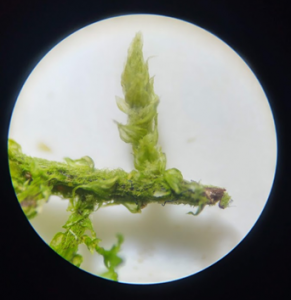

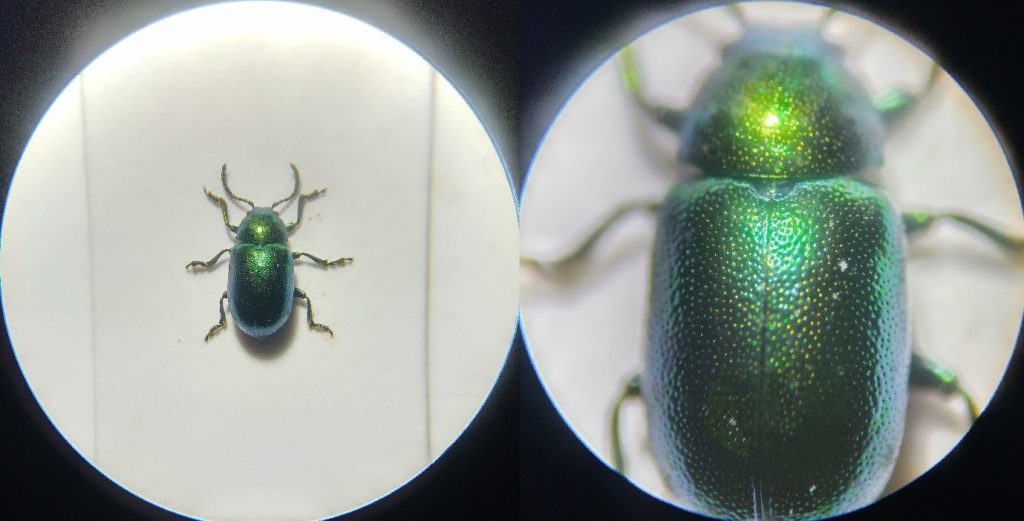

There is something wonderful about microscopy – the examination of tiny insects and fungal spores feels like peering into another world that we seldom have the privilege to observe. For some naturalists, a stereo microscope might seem like an unnecessary extravagance but for many who work with tiny subjects like invertebrates, lichenous fruiting bodies or bryophyte spores they can shed a light on fascinating diagnostic features that a hand lens simply doesn’t have the power to show.

There is something wonderful about microscopy – the examination of tiny insects and fungal spores feels like peering into another world that we seldom have the privilege to observe. For some naturalists, a stereo microscope might seem like an unnecessary extravagance but for many who work with tiny subjects like invertebrates, lichenous fruiting bodies or bryophyte spores they can shed a light on fascinating diagnostic features that a hand lens simply doesn’t have the power to show.

We have recently added the Motic SMZ-140 and -161 series to NHBS’s range of stereo microscopes. Known for their good quality, robust entry-level optics as well as their laboratory standard equipment, Motic Europe has an excellent reputation among industry professionals and hobbyists alike. As such, we were excited to have a look at their mid-range LED model, the SMZ-140-LED. Designed to be as flexible as possible, this series has the advantage of a very wide 10x-40x magnification range, rather than the 20x-40x that most stereomicroscopes offer in this price range, as well as reflected and transmitted LED illumination and fully modular design for further customisation.

How We Tested

The SMZ-140 was tested thoroughly with a variety of different subjects. Specimens used originated from an invertebrate monitoring program close to our South Devon office, along with a variety of botanical subjects selected to test the microscope’s use in different disciplines. The image clarity and brightness across its zoom range were noted, as well as our impressions of the mechanical systems such as zoom, movement focus. The different accessories such as stage plates and options like lighting methods were also used to get as complete a picture of the systems’ utility across as complete a range of applications as possible.

What We Found

First Impressions

The first thing that is apparent about the SMZ-140 is the compact design and packaging. The box that it is supplied in manages to be easily a quarter the size of other models of a similar price and specification, and noticeably lighter too, without sacrificing any protection. This is because the microscope itself is remarkably compact, the base built to centre the weight on a smaller footprint than any other I have seen. This makes a real difference when workspace is limited, or if there is a chance that the microscope might need to be moved to different venues. It is supplied with the head detached from the body but setting it up is a simple and intuitive process that takes no more than a few minutes. Comprehensive instructions are also supplied.

The look of the SMZ-140 is simple but professional. The positioning of the zoom and focusing wheels is intuitive, and both move smoothly without resistance or kick back. The supplied stage plates, one reversible black/white plate for use with the reflected illumination system and one translucent plate to complement the transmitted illumination option, are also robust and resistant to scratching. One slight drawback is the lack of any lens caps, but good-quality dust cover is supplied to protect the workings from any ingress.

The working distance, that is the distance between the head and the staging platform, is 80mm, which allows for easy manipulation of the subject, including dissection where appropriate. The pinions should be sufficient to hold most subjects in place and have an impressive range of movement for use with larger samples.

Eyepieces and Illumination

The eyepieces are comfortable to use, padded with rubber and with an adjustable interpupillary distance. Each one has a +/- 5 diopter adjustment, allowing for easy adjustment to the user’s eyes. The whole head piece can be moved from side to side at the user’s convenience. The zoom wheel moves easily and is mounted on the head, while the larger focusing wheel is placed on the pillar to minimize confusion between the two while the user is looking through the eyepieces.

The standard 10x eyepieces that come supplied with this model can be swapped out for 15x, 20x, or 30x options, and the 1-4x objective lens can be removed and replaced with lower magnification options such as 0.5 times as desired.

The illumination is bright and can be adjusted at will, allowing for the user to adjust it if they find themselves dazzled or if working with a reflective subject such as a beetle that risks being washed out by a powerful light source. The transmitted and reflected options are activated via separate switches, meaning that both could be used simultaneously if so desired.

The LED bulbs on this model are of use to many researchers as they provide heat-free illumination and will therefore not damage live specimens or dry out those that are at risk of desiccation, such as insects or lichen.

Magnification and Image Quality

In contrast to the standard 20x-40x zoom of most stereomicroscopes in this price range, the SMZ-140 has a range of 10x-40x. As previously stated, this can be increased up to 120x with 30x eyepieces, but for the vast majority of applications the standard range should be perfectly adequate.

The low minimum zoom makes the microscope very useful for larger specimens or jobs that require a wider field of view such as mounting medium sized insects. Motic’s lenses provide a clear, crisp, and bright image even up to the maximum magnification of 40x. The user might struggle with the diagnostic features of very tiny subjects, i.e. those below 1mm, but for the price range the image of the SMZ-140 is among the best I have seen. The keystone effect is noticeable with this model, as it is in most Greenough system stereo microscopes, but is barely perceptible next to the natural variation in focus of three-dimensional samples.

The 20x and 30x click stop feature of the zoom wheel is very useful when working at higher zoom levels, as it allows the user to standardize the magnification at which specimens are examined and makes accurate record keeping easy. The magnification is also indicated on the wheel for visual reference.

Our Opinion

With the SMZ-140-LED, Motic establish themselves as manufacturers of excellent, affordably priced stereo microscopes ideal for almost any use that a naturalist could desire. Among a crowded market of models with very similar specifications, it distinguishes itself through its compact, lightweight design, robust build, and wide zoom range. It is easy to use and provides consistently excellent results, and the modularity of its design along with a good range of accessories allows for simple adaptation to a wide array of jobs.

While some microscopists might prefer to look at more expensive models with wider lens apertures for an even brighter image (such as the SMZ-160 series), or even high-end models that utilize the advanced common mains objective optical system, among models in its price range the 140 certainly stands out. It’s clear that it is designed with flexibility in mind, and as such it is an ideal choice for anyone looking to dive a little deeper into the wonderful world of the tiny.

The SMZ-140-LED can be found here. Our full range of stereo microscopes can be found here. For further information why not check out Insect Microscopy by Andrew Chick.

If you have any questions about our range or would like some advice on the right product for you then please contact us via email at customer.services@nhbs.com or phone on 01803 865913.

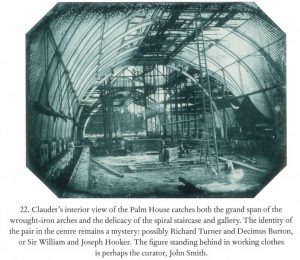

Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today

Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

Why were palms so important to the Victorians?

Why were palms so important to the Victorians? How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?

How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?