In her debut book, Meetings with Moths, ecologist Katty Baird delves into the Scottish landscape in search of some incredible moths that have formed remarkable relationships, responses and adaptations in order to prevail. Meetings with Moths is a journey through all seasons, across a range of habitats and taking in each stage of the moth life cycle; investigating the ways in which moths utilise sight, sound, and smell in their lives, as well as their unique camouflage abilities and navigational skills. Along the way Katty meets with fellow ecologists, researchers and moth enthusiasts and draws on past research, records and recorders to explore the changing fates of these often overlooked (by their very nature) insects, and the intricacies of their fascinating lives.

In her debut book, Meetings with Moths, ecologist Katty Baird delves into the Scottish landscape in search of some incredible moths that have formed remarkable relationships, responses and adaptations in order to prevail. Meetings with Moths is a journey through all seasons, across a range of habitats and taking in each stage of the moth life cycle; investigating the ways in which moths utilise sight, sound, and smell in their lives, as well as their unique camouflage abilities and navigational skills. Along the way Katty meets with fellow ecologists, researchers and moth enthusiasts and draws on past research, records and recorders to explore the changing fates of these often overlooked (by their very nature) insects, and the intricacies of their fascinating lives.

Following a Zoology degree and PhD, Katty Baird continued in academia as a postdoctoral research fellow, studying insect-plant interactions. She now works as an ecologist, recording and monitoring invertebrates throughout Scotland. Since 2016 she has run the Hibernating Herald project and in 2019/20 she wrote a popular blog, recording moths on the Whittingehame Estate in East Lothian.

We were delighted to be able to ask Katty a few questions prior to the release of Meetings with Moths.

There are some beautiful ponderings throughout the book alluding to your early encounters and memories with moths. Could you tell us a little more about what got you hooked on moths, and how you’ve come to work so closely with them, both in the wild and in your work with museum collections?

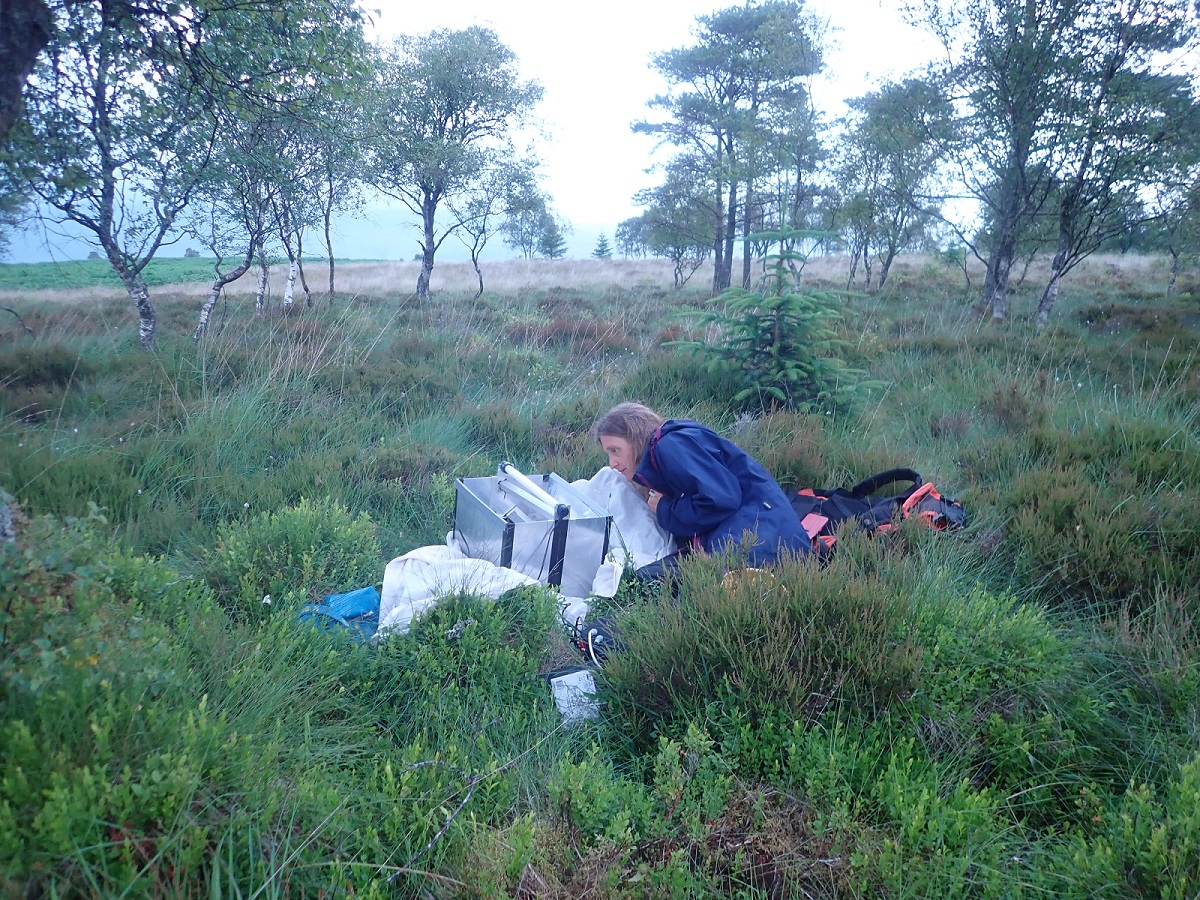

I’m a big fan of all insects (and other invertebrates) and generally, as long as I’m learning new things, I’m happy. However, with moths, I love that you don’t need a microscope to enjoy their beautiful variety and a light trap means many species can be enjoyed relatively easily. It’s hard not to be impressed by the stature of a Poplar Hawk-moth or the delicacy of a White Plume Moth. They are also great insects to share with others; excellent ambassadors for our often-overlooked smaller fauna.

I’m a big fan of all insects (and other invertebrates) and generally, as long as I’m learning new things, I’m happy. However, with moths, I love that you don’t need a microscope to enjoy their beautiful variety and a light trap means many species can be enjoyed relatively easily. It’s hard not to be impressed by the stature of a Poplar Hawk-moth or the delicacy of a White Plume Moth. They are also great insects to share with others; excellent ambassadors for our often-overlooked smaller fauna.

Moths are a relatively well-studied insect group in the UK which provides useful context for me to understand my own recording efforts. But at the same time, there is so much we don’t know, particularly about moth life cycles and ecology, leaving plenty of opportunity for making new discoveries!

As for museum collections, through my endeavours here, I’ve discovered a treasure trove of information waiting to be unlocked. Sadly, there just isn’t the resources to extract this data and make it available to all. I’m fortunate that I’ve been able to offer some time to help, though it wasn’t entirely altruistic – I have also learned much about moths and moth recording in the process; I only wish I had more time to give.

The book contains many fascinating introductions to prominent lepidopterists, ecologists and enthusiasts, some of whom are at the forefront of current moth research, and others from the early days of modern appreciation and understanding. Did you set out with clear influences to research and include in the book, and have some surprised you along the way?

I’m naturally quite shy and like nothing more than being outdoors on my own, but I think this book has highlighted how important people in the moth-ing community have been to me. An initial aim of the book was to share some of the wonders of our native moths through my own experiences of seeking them out, but as I got stuck into the writing, I realised that my best stories were those that included the people I’ve met along the way. Lots of wonderful characters, a few quirks here and there, each pursuing moths in their own way but ultimately for the same reason: because they love seeing these insects. Wanting to know more about the animals and plants around me has led me to an interest in moths, but my fellow Lepidopterists have definitely enhanced it.

From your experiences working among archives of invertebrate specimens, do you think the character of a collector comes through in their collections?

Yes, I think so, particularly in archives with accompanying notes and diaries. Just as contemporary recorders have slightly different motivations; for example seeing as many species as possible or understanding the moths of a particular area well, so did collectors from the past. The details that are written on the labels, the handwriting, the comments in notebooks all hint at the personality of the characters involved. I’m not sure our modern legacy of spreadsheets and digital photo archives provide the same back story. Of course in many cases – a bit like social media feeds – only the significant finds and achievements get documented for prosperity. Failures are brushed aside and conveniently forgotten.

Yes, I think so, particularly in archives with accompanying notes and diaries. Just as contemporary recorders have slightly different motivations; for example seeing as many species as possible or understanding the moths of a particular area well, so did collectors from the past. The details that are written on the labels, the handwriting, the comments in notebooks all hint at the personality of the characters involved. I’m not sure our modern legacy of spreadsheets and digital photo archives provide the same back story. Of course in many cases – a bit like social media feeds – only the significant finds and achievements get documented for prosperity. Failures are brushed aside and conveniently forgotten.

As the title suggests, you meet with many incredible moths within the journey of this book, and you deftly extol their virtues while inspiring the reader to do the same. What initial advice would you offer to those wanting to start meeting moths?

Get out there and start looking! Try an early morning check of walls of buildings that have been lit overnight (toilet blocks are surprisingly good) or wandering around at dusk looking at flowers with a torch. To start with, just enjoy finding them but as your curiosity is piqued you will probably want to know their names. There are various guidebooks and online identification resources – try the ‘What’s Flying Tonight?’ app or join a social media moth group (there are many!). Best of all though is to learn from and be inspired by others. Many local Butterfly Conservation groups run moth events where you can see moths, and some have light traps to borrow if you want to try before you buy. Once you start using a light trap, you will wonder what took you so long.

It’s clear that moths face a myriad of existential challenges in our changing climate and with many unique habitats and relationships under increasing threat, the stories in your book of their adaptations and adjustments in life are remarkable and admirable. What do you see as the conservation priorities that would actively support greater moth abundance and diversity in the UK?

We need to improve, connect and protect habitats beyond the limited spaces within nature reserves so moths can move across landscapes more easily. This means things like limiting chemical use, reducing grazing pressures, flailing hedges and verges less frequently, and allowing areas for nature to do its own thing. It can be helpful to focus on saving a particular species of moth, or a particular habitat, but it is the wider benefits of that focus that will make the most difference.

It’s easy to feel a bit helpless, but planting gardens, balconies, window boxes with plants that insects can use, will make a difference to your local moth populations and has the bonus of attracting them to you.

I really enjoyed reading about how you return to certain species each year to check in with them in both new and familiar places. Could you tell us a bit about a species that calls you back, and why they speak to you?

It has to be the Tissue, Triphosa dubitata. In Scotland, this is sparsely distributed and quite hard to catch up with, but through seeking overwintering adults out in various caves and mines we are learning a bit more about its life here. They arrive in these overwintering sites in late summer, and for the last six years, I’ve got inexplicably excited when seeing the first ones of the year. Even though they are almost expected in some places, I still get a buzz from seeing them. It is a beautiful moth, with lovely patterns of silver, grey and pink. Each one has slightly different patterning which makes them individually recognisable and easy to follow over the winter (though I’ve stopped short of giving them names). A big part of the attraction of finding Tissue is exploring the caves and mines where they turn up. On a bleak October day, with the wind and rain lashing, the peace and restoration of being enveloped in the darkness of a cave in the company of beautiful moths can’t be replicated.

Is there a moth you can tell us about that you’ve not met that you’re eager to see?

There are many species I’ve still to meet. If I put my mind to it, I expect I could see a lot of them by visiting known sites at the right time of year but I’m not in that much of a hurry. In my home county of East Lothian, one of my most-wanted is Portland Moth. It’s a rather optimistic wish; this is a rare moth anywhere in the UK and hasn’t been seen for about a hundred years in East Lothian. They live in dune areas, but we don’t really know exactly how they like their dunes to be. We’re not even sure what range of plants the caterpillars will eat. It is one of the species that Butterfly Conservation Scotland is hoping to find out more about, so I’m hoping to join them on some of their planned searches for caterpillars at known sites further north. Nocturnal crawling around sand dunes with a bunch of moth enthusiasts can only be fun.

Lastly, I’d like to ask what you have in mind next, if there are further writing projects you’d like to tell us about or a new line of research on the horizon?

I would love to write more about Alice Balfour and other forgotten Scottish entomologists from the past. There are some interesting stories to be told. I would also like to do more moth science. Butterfly Conservation have a list of ‘priority species’, rare moths that they want to know more about. If I could, I would pick one of these, go and base myself somewhere in the middle of Scotland and spend my days and nights finding out all there is to know about them. Anyone is welcome to come and help!

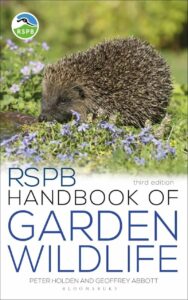

Meetings with Moths

Meetings with Moths

By: Katty Baird

Hardback | April 2023 | Forth Estate

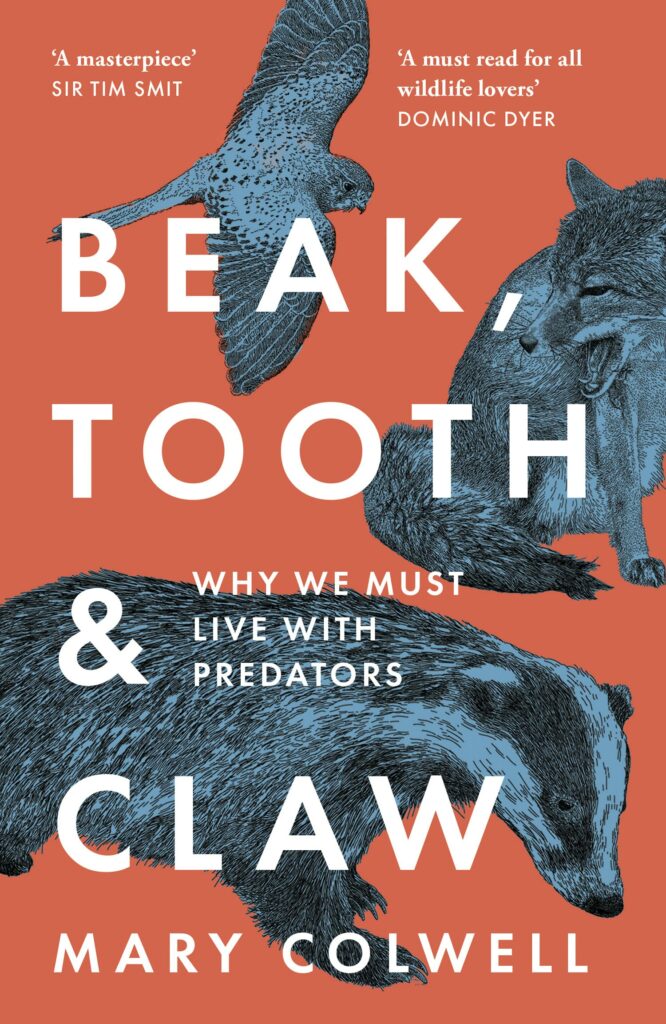

Alick Simmons is a veterinarian and a naturalist. During a career spanning 35 years he held the position of the UK Government’s Deputy Chief Veterinary Officer (2007-2016) and the UK Food Standards Agency’s Veterinary Director (2004-2007). In 2015 he began conservation volunteering, and has been involved in survey projects for both waders and cranes. He is currently chair of the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare and the Humane Slaughter Association. He also serves as a Trustee of the Dorset Wildlife Trust and chairs the EPIC disease control steering group on behalf of the Scottish Government.

Alick Simmons is a veterinarian and a naturalist. During a career spanning 35 years he held the position of the UK Government’s Deputy Chief Veterinary Officer (2007-2016) and the UK Food Standards Agency’s Veterinary Director (2004-2007). In 2015 he began conservation volunteering, and has been involved in survey projects for both waders and cranes. He is currently chair of the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare and the Humane Slaughter Association. He also serves as a Trustee of the Dorset Wildlife Trust and chairs the EPIC disease control steering group on behalf of the Scottish Government.

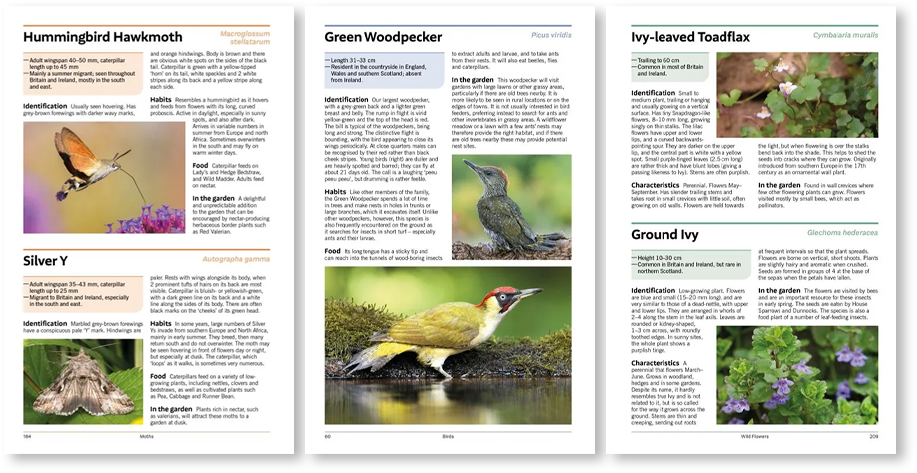

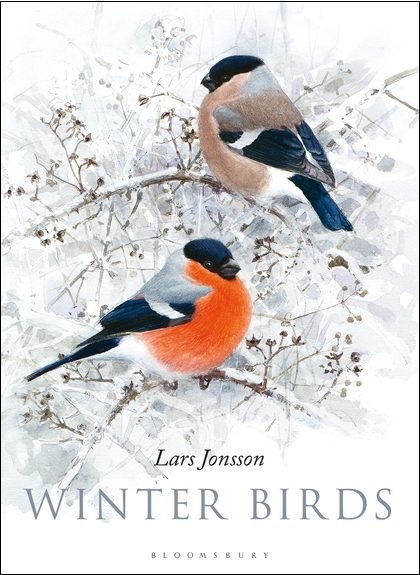

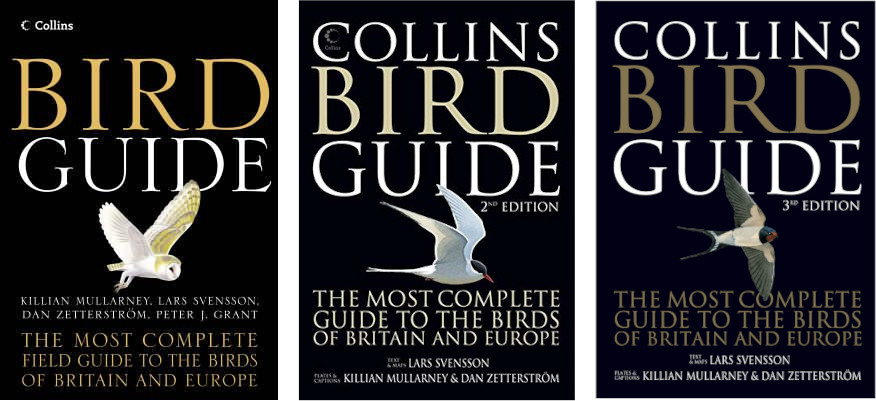

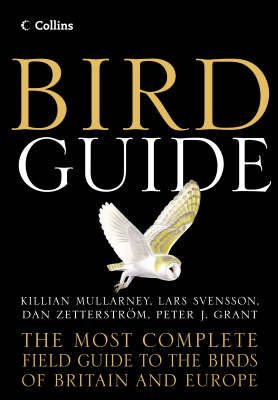

In 1986, well respected identification experts Peter Grant and Lars Svensson came together to begin working on just such a thing. To illustrate the book they recruited artist Killian Mullarney from Ireland, whose painstakingly detailed work was conducted from first-hand field experience, lending it a lively and lifelike quality. Creating artwork in this way, however, proved to be a slow process, and even with the addition of another illustrator- Dan Zetterström – the book was 13 years in the making. Unfortunately, Peter Grant died in 1990, some time before its eventual publication in 1999, so he never got to see the final result.

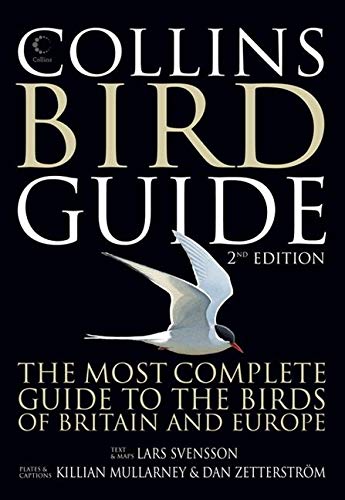

In 1986, well respected identification experts Peter Grant and Lars Svensson came together to begin working on just such a thing. To illustrate the book they recruited artist Killian Mullarney from Ireland, whose painstakingly detailed work was conducted from first-hand field experience, lending it a lively and lifelike quality. Creating artwork in this way, however, proved to be a slow process, and even with the addition of another illustrator- Dan Zetterström – the book was 13 years in the making. Unfortunately, Peter Grant died in 1990, some time before its eventual publication in 1999, so he never got to see the final result. The second edition of the Collins Bird Guide was published in 2010 to reflect new and revised taxonomy, and included both expanded text and additional illustrations. The

The second edition of the Collins Bird Guide was published in 2010 to reflect new and revised taxonomy, and included both expanded text and additional illustrations. The