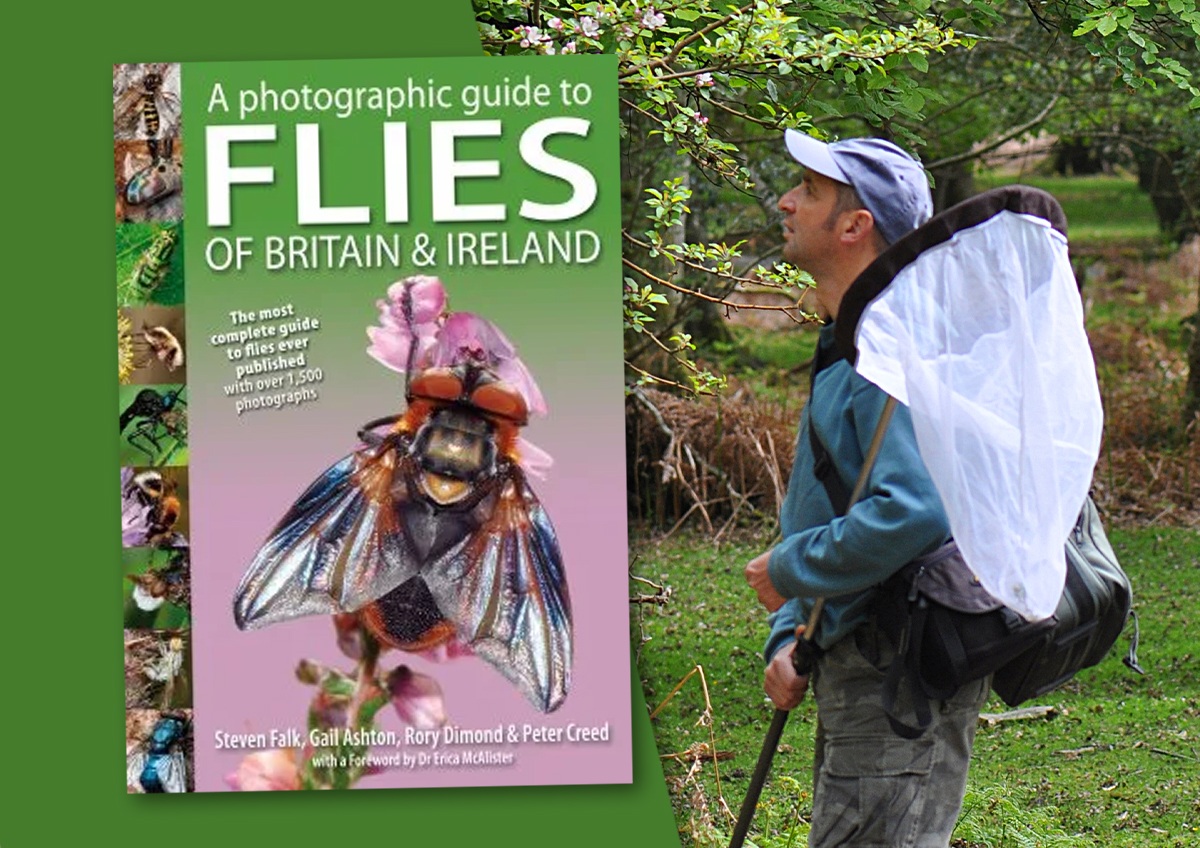

Over recent decades various ‘difficult’ insect groups have gradually been brought within reach of the non-specialist thanks to developments in field guides. Flies, however, have remained something of a final frontier, and it’s easy to see why – with more than 7,000 species in Britain alone, creating an accessible and user-friendly guide to this group is a daunting task.

Now, however, a team of expert field entomologists have stepped up to the challenge and produced A Photographic Guide to Flies of Britain and Ireland – the first guide to ever tackle this amazingly diverse insect order as a whole. With beautiful photography and clean, concise text, this book is set to put flies on par with bees and other more ‘popular’ insect relatives, and bring them their due share of attention in the interests of general naturalists.

Ahead of publication, we had the pleasure of talking to lead author Steven Falk about the book’s development and the rewards of fly-recording.

Firstly, how did the book come about?

The idea for the book initially came from Peter Creed, the Creative Director (and Designer) at NatureBureau, which owns Pisces Publications. He wanted a book resembling A comprehensive guide to Insects of Britain & Ireland by Paul Brock, published by Pisces in 2014 (with a 2019 second edition) but concentrating purely on Diptera. He approached Gail Ashton who was helping to man the Dipterists Forum stand at one of the Amateur Entomology Society autumn fairs to discuss the possibility of doing such as book in conjunction with the Forum. Gail eventually agreed to help write it and asked Rory Dimond to assist. I become involved about one-third of the way through the project when it was clear that the book would need several hundred of my images to make it viable (we needed at least 1,500 accurately identified fly photos for the book), and my role later expanded into that of primary author. The internet has patchy information on Diptera, and what does exist can be misleading or out of context with the British fauna, so you need lots of first-hand experience to avoid creating misleading text. Even taking information from trusted literature can be challenging when it needs it be distilled down to short, snappy species accounts. Gail and Rory helped ensure that the text was not overly technical, though inevitably a book on flies ends up more technically worded and microscope-based than a book on butterflies or dragonflies. But we provide good diagrams and a large Glossary to help readers negotiate this. The proof-reading and creative discussions by the members of the team have been very important, making for a much better publication. It helps that all four of us share a passion for breaking down barriers in entomology and enthusing general naturalists about flies rather than just serving the converted. We were also keen to produce a more visually exciting and enticing book than much of the more technical fly literature and online resources available for flies. But we have still signposted those other resources for readers who want to develop a deeper understanding of flies and take things further by providing a good Bibliography. This covers all the key identification literature relevant to a British or Irish audience, both printed and that which is freely downloadable from the internet.

Let’s talk about flies themselves. What makes them so important, and what can recording flies tell us about the state of the natural world?

There are currently about 7,300 species of fly on the Britain and Ireland list, with the possibility of over 10,000 species being present, as we find dozens of new ones each year and DNA is revealing lots of cryptic species. So, if you are passionate about biodiversity and serious about its conservation, you cannot ignore flies. They are typically the most speciose eukaryotic group at a wildlife site and are also incredibly diverse ecologically. I regularly record over 500 fly species at a good wildlife site, and the Windsor Forest and Great Park list stands at almost 2,000 species. Those massive fly assemblages including predators, parasites, saprophages, herbivores, fungivores, pollinators, and so on. What is more, fly assemblages can be found from the intertidal zones of the coast to the tops of our highest mountains. Having some idea of what all those flies are and what they need in terms of breeding sites and adult feeding, makes you view habitats, sites and landscapes in a very different way to a botanist or general ecologist. You notice and value microhabitats and other features that others miss or under-value, such as sap runs or water-filled rot holes in old trees, different sorts of dung, different sorts of ‘wet’, different sorts of ‘decay’, different sorts of ‘bare ground’ and so on. Flies also make you think much harder about aspects such as habitat combinations and mosaics (bearing in mind that fly larvae and adults often have very different needs), habitat connectivity, habitat condition, site history, microclimate, seasonality and climate change. Dipterists are often pretty good botanists and habitat ecologists, but adding flies and other insects to the equation provides a much bigger ‘vocabulary’ when you are trying to understand and interpret the environment. That was particularly important a few years ago when several professional entomologists including myself were assessing the emerging Biodiversity Net Gain metrics. We were able to articulate some powerful feedback to Defra and Natural England concerning the over-simplistic metrics that were emerging, and the serious impact that might have for protecting invertebrate (as well as general) biodiversity. Flies are also really important in ecosystem services (e.g. crop pollination, pest control, sewage treatment). There is strong evidence that they may be more important than bees for the pollination of certain crops, and for general wildflower pollination in habitats like montane grassland and saltmarsh. The role of flies in ecosystems and food webs is something that comes through strongly in the book.

Faced with such a huge group, how did you go about deciding which species to include?

Being a photo-based book, the choice of what species to include is heavily based on what photos are available. But many fly photos on the internet are inaccurately identified, so we had to make sure that such images were either avoided, or (if we could tell what they actually were), used correctly. So, if a species lacked a decent photograph, it could not be subject of a typical species account, though we have name-checked many species without accompanying images within the Similar Species section at the end of many species accounts. For some smaller, iconic families, such as robber flies, horseflies, soldierflies and bee-flies, every published British and Irish species is included. For hoverflies, it is closer to about two-thirds of the fauna, and for groups like parasite flies and the housefly family, it is about half the fauna. In these instances, we tried to include representatives from most if not all the genera in a family and tried to ensure most of the more distinctive-looking or ecologically interesting species were covered. For some of the more obscure or difficult families, only brief coverage is provided. But all 108 fly families present in Britain and Ireland get some level of coverage in the book, which is quite an achievement.

Can you tell us a bit about the book’s approach – what can readers expect from the species accounts?

The book is arranged taxonomically following the sequence of the 2025 Checklist of Diptera of the British Isles which is hosted (and regularly updated) on the Dipterists Forum website. The individual species accounts mostly have a consistent format. It starts with an indication of the size of a fly, either using wing length or body length, then a basic description of the species, often carefully worded to highlight differences from other similar species. We then describe Habitat, Distribution, Season, and (for parasitic or herbivorous species) Hosts. The species accounts are accompanied by a map and photograph or, indeed, two or more photos for species with strong sexual dimorphism or several colour forms. A section on Similar Species is also used in many cases, namechecking other flies that might be confused with the main subject. These extra species are also sometimes provided with a map and photo. It means that about 1,300 species of fly get namechecked by the book (about 1,100 of these with standard species accounts). But it often came down to what space was available on each page spread as to what got covered. Suffice to say we used a flexible and opportunistic approach to ensure we made the most of each double-page spread.

The guide is beautifully laid out and packed with outstanding imagery. Was it a challenge gathering photos for all the flies you wanted to feature?

About 40% of the photos come from me and were already featured on my Flickr site. That made image selection for some families much easier and meant that Peter Creed could quickly download any of my images, and if I disagreed with an image choice, I could quickly send him hyperlinks to the image I preferred. Peter, who is also a keen insect photographer (and always thinking of the next potential Pisces book), provided about 20% of the images. We also turned to reliable British insect photographers such as Paul Brock, Simon Knott, Kevin McGee and Ian Andrews, and approached other photographers if we spotted images of further species on the internet (or better images of a species than we had to hand). The result is that we’ve ended up with over 1,500 images of over 1,100 species and have used images from 186 photographers. Suffice to say, we are immensely grateful to everyone who provided images.

For the general naturalist who has yet to become a fly convert, what can you say about the rewards of studying these insects?

Flies have huge intrinsic interest in terms of interesting appearances (including mimicry, loss of wings, bizarre wing markings and strange body modifications), interesting lifecycles, interesting behaviours, and their importance in ecosystem services. They are great fun to photograph (with cameras like the Olympus TG series making it easier than ever), and it is relatively easy to identify some from photos, either using this book, or by posting images on the various Facebook groups that cover flies (where others can provide feedback on what they think your photo is). Flies also provide an incredibly powerful framework or lens for interpreting and understanding habitats and landscapes better, as explained above. I think that aspect (using flies to view understand the environment more critically) is truly exciting and very rewarding.

What tips would you give for someone looking to take a deeper interest in flies and find a greater range of species?

Buying a stereo zoom microscope makes a big difference as it allows you to identify flies with much greater confidence and appreciate the beauty in the details of their morphology. While we are aware that many users of the book will not want to go down the road of collecting and killing flies for the purpose of identifying them critically, that is the approach that is generally needed to develop long and accurate species lists for a site. There is a limit to what can be achieved through photography. But going down the collecting route also means buying an insect net, tubes and pooters, insect pins and storage boxes for pinned specimens, plus obtaining some of the key literature listed in the book’s extensive bibliography, such as British Hoverflies (Stubbs & Falk 2002), published by the British Entomological and Natural History Society. I would also strongly recommend joining the Dipterists Forum. This is the national society for the study of flies and is very friendly and well-organised. It publishes a regular newsletter (Bulletin of the Dipterists Forum) and journal (Dipterists Digest) and organises regular indoor and outdoor events. It has a great website that can be used by non-members but has extra resources for logged-in members. The Forum acts as an umbrella for almost 30 family recording schemes or study groups, some of which have their own Facebook groups or satellite websites. Nowhere outside of Britain and Ireland comes to close to matching that offer.

Finally, what do you hope the book will do for interest in flies and fly recording?

We are hoping it has a major impact, not only by making general naturalists more aware of, and sympathetic towards flies but also by encouraging more naturalists to take up formal recording of flies as outlined in the previous response. Many parts of Britain have few (if any) resident fly recorders, and it would be especially good to promote recording in those areas, even if it is just the recording of easier groups such as hoverflies. Climate change is having a profound impact on insect life, and the more data we get, the more we understand that impact and formulate strategies to counter it through improved habitat management and other land use decisions. We hope that this book will support constructive dialogue – ecologists, farmers, planners all a little bit more familiar with flies, able to be enthusiastic about them and their conservation.

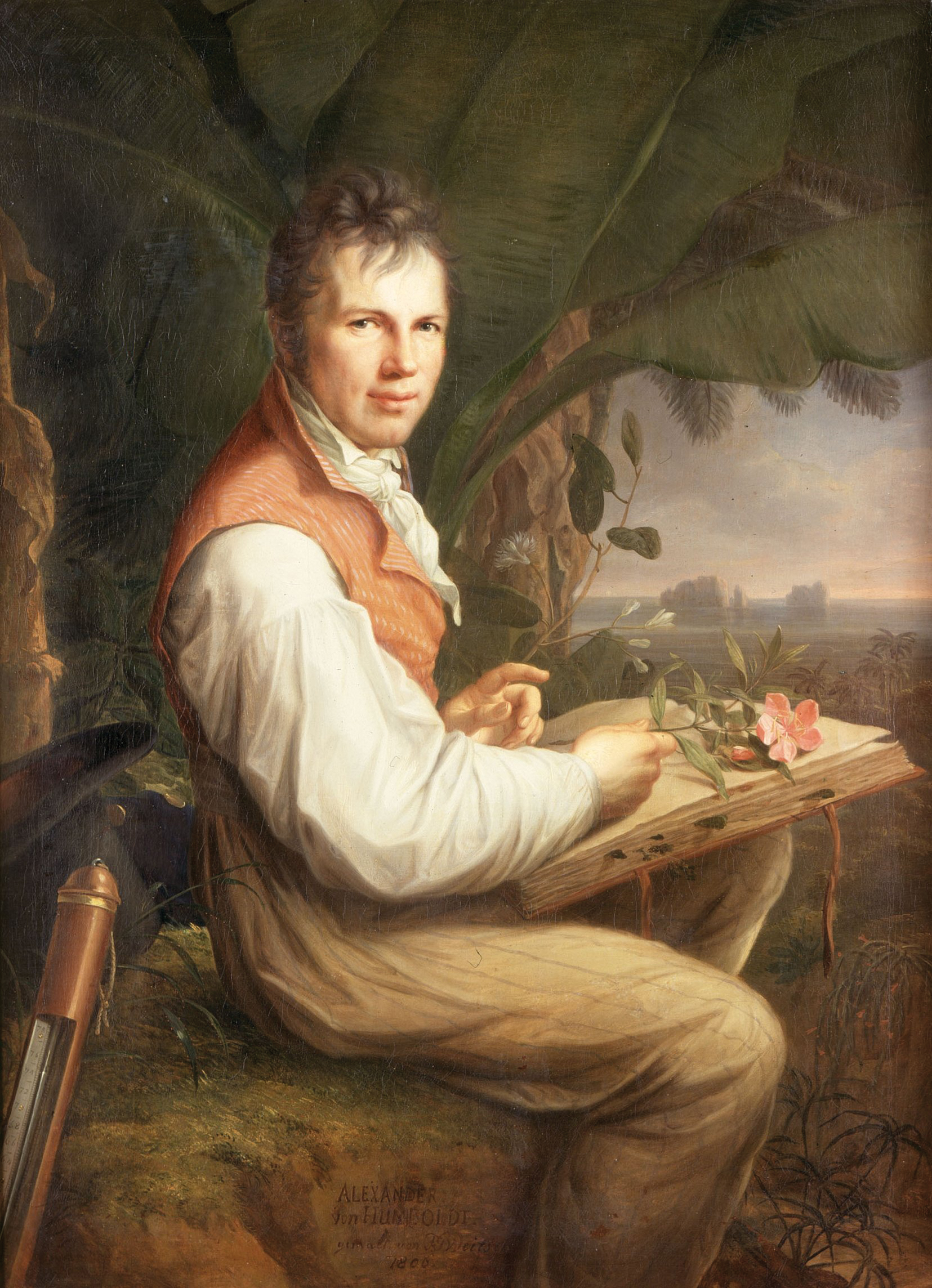

Sverker Sörlin is an author, historian, and science communicator. He is currently Professor of Environmental History at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

Sverker Sörlin is an author, historian, and science communicator. He is currently Professor of Environmental History at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

An inspiring story of love, connection and the healing power of nature, author

An inspiring story of love, connection and the healing power of nature, author

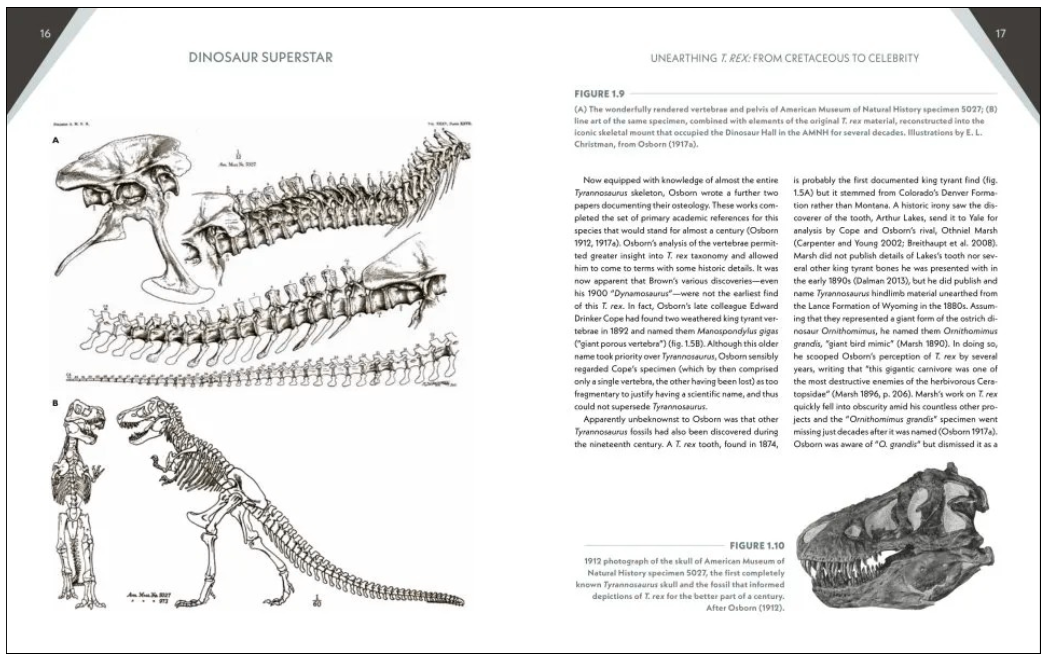

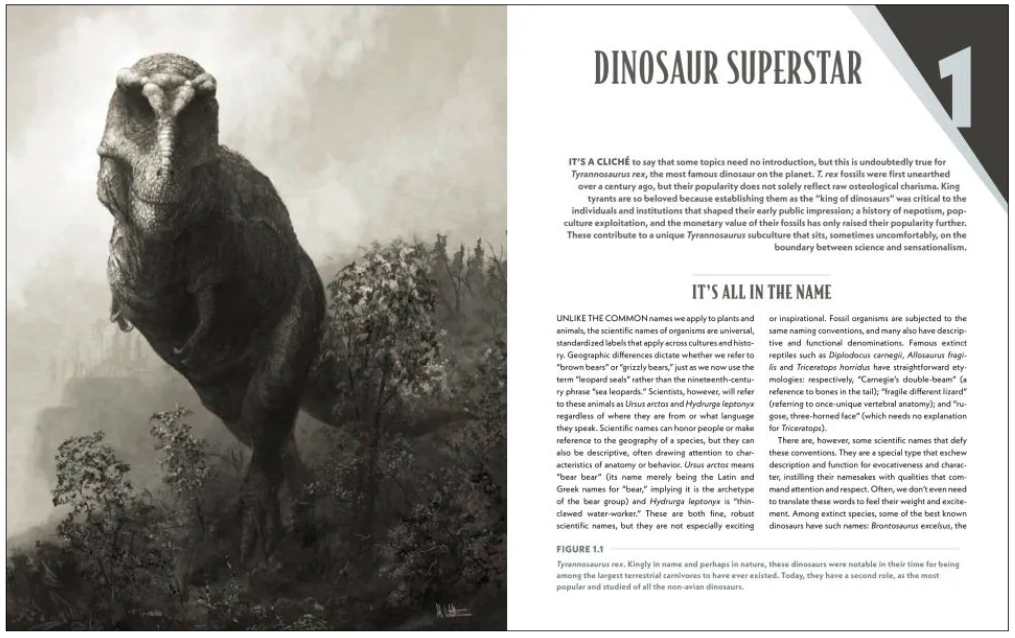

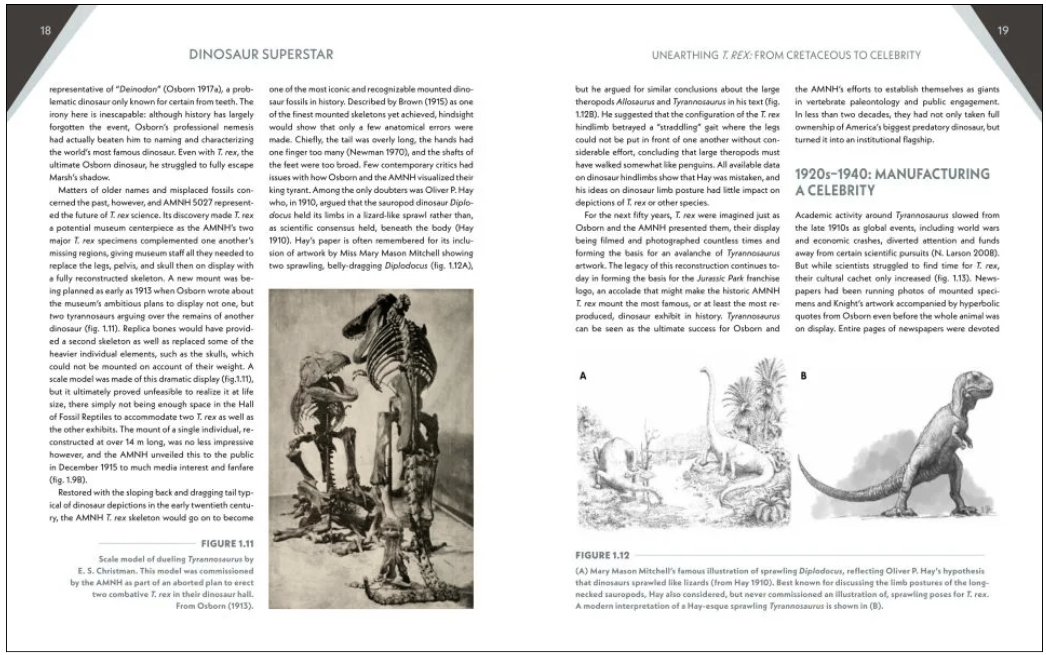

Given how frequently the name T. rex crops up, you might even get a bit annoyed: not you again! All the more reason to read this book. Witton is acutely aware that a veritable subculture has grown up around this one species that “sits, sometimes uncomfortably, on the boundary between science and sensationalism” (p. 1). These popular depictions, often carrying with them an air of scientific authority, bleed into people’s consciousness, creating something less of a dinosaur and more of a chimaera, with traits both exaggerated and fictional. One of Witton’s most important goals with King Tyrant is to “deconstruct hype and controversy” (p. 41). The first chapter daringly combines a précis of the first century of research with an examination of the sociological side. How did this particular species become palaeontology’s rock star? It is a fascinating history that starts at the American Museum of Natural History who promoted it to attract large crowds. It was “proverbial lightning in a bottle” (p. 278), with an influential legacy that lasts to this day in movies, documentaries, and merchandise. And yet, popular depictions “have nothing on what science tells us about the reality of Tyrannosaurus rex” (p. 279).

Given how frequently the name T. rex crops up, you might even get a bit annoyed: not you again! All the more reason to read this book. Witton is acutely aware that a veritable subculture has grown up around this one species that “sits, sometimes uncomfortably, on the boundary between science and sensationalism” (p. 1). These popular depictions, often carrying with them an air of scientific authority, bleed into people’s consciousness, creating something less of a dinosaur and more of a chimaera, with traits both exaggerated and fictional. One of Witton’s most important goals with King Tyrant is to “deconstruct hype and controversy” (p. 41). The first chapter daringly combines a précis of the first century of research with an examination of the sociological side. How did this particular species become palaeontology’s rock star? It is a fascinating history that starts at the American Museum of Natural History who promoted it to attract large crowds. It was “proverbial lightning in a bottle” (p. 278), with an influential legacy that lasts to this day in movies, documentaries, and merchandise. And yet, popular depictions “have nothing on what science tells us about the reality of Tyrannosaurus rex” (p. 279). T. rex, more than any other species, attracts a lot of fringe ideas from inside and outside of academia, and Witton leaves no rock unturned. On the one hand, there are the minority views and “non-troversies” (thanks Witton, I am stealing that brilliant term) that get far too much airtime, such as the existence (or not) of a dwarf species, “Nanotyrannus“, or the scavenging hypothesis, the notion that T. rex was a scavenger rather than a hunter. Needless to say, neither idea curries much favour among professionals. On the other hand, actual scientific debates are often ignored by the press. Opinions are divided on whether dinosaurs were already on their way out before the asteroid impact or were still in their prime. Witton provides the best overview of this topic that I have read so far.

T. rex, more than any other species, attracts a lot of fringe ideas from inside and outside of academia, and Witton leaves no rock unturned. On the one hand, there are the minority views and “non-troversies” (thanks Witton, I am stealing that brilliant term) that get far too much airtime, such as the existence (or not) of a dwarf species, “Nanotyrannus“, or the scavenging hypothesis, the notion that T. rex was a scavenger rather than a hunter. Needless to say, neither idea curries much favour among professionals. On the other hand, actual scientific debates are often ignored by the press. Opinions are divided on whether dinosaurs were already on their way out before the asteroid impact or were still in their prime. Witton provides the best overview of this topic that I have read so far.