Looking for experts on British shores, the names of Frances Dipper and Paul Naylor quickly come to mind. With their combined lifetimes of experience in marine biology, a collaboration on a book on the wonderful British seashores is sure to be a success. At NHBS, we consider it a privilege to have Coastal Seas in our catalogue – a book that offers deep insight in the state and the wonder of British coastal seas, complemented by awe-inspiring photography.

Looking for experts on British shores, the names of Frances Dipper and Paul Naylor quickly come to mind. With their combined lifetimes of experience in marine biology, a collaboration on a book on the wonderful British seashores is sure to be a success. At NHBS, we consider it a privilege to have Coastal Seas in our catalogue – a book that offers deep insight in the state and the wonder of British coastal seas, complemented by awe-inspiring photography.

While celebrating the release of this important book, we were honoured to interview the authors.

Frances Dipper is an independent marine biologist whose career spans over four decades of studying, lecturing, award-winning writing, and scuba diving. Her extensive bibliography reflects her deep knowledge, and she continues to share this through talks in Cambridgeshire and beyond.

Paul Naylor is also a marine biologist, as well as an underwater photographer and filmmaker. He is passionate about sharing his expertise to inspire appreciation and to draw people into the wondrous world of the marine environment.

How did you come to the decision to work together on “Coastal Seas”, and how did you complement each other in the writing of this book?

Frances: as the saying goes ‘two heads are better than one’ and in our case two marine biologists and lifelong divers are as well. When I was invited by Bloomsbury to write this volume, I immediately thought of Paul’s impressive underwater photography and story-telling skills and thought it would be great fun to collaborate on the project.

Paul: It really stemmed from having the same passion for observing and studying the wonders of our coastal seas and, even more importantly, sharing them with as wide an audience as possible. The collaboration worked well because we have similar overall ideas and are long-time friends, but have always worked separately, so we brought very different experiences to the project.

Over the span of your careers, what visible changes have you observed in British coastal seas?

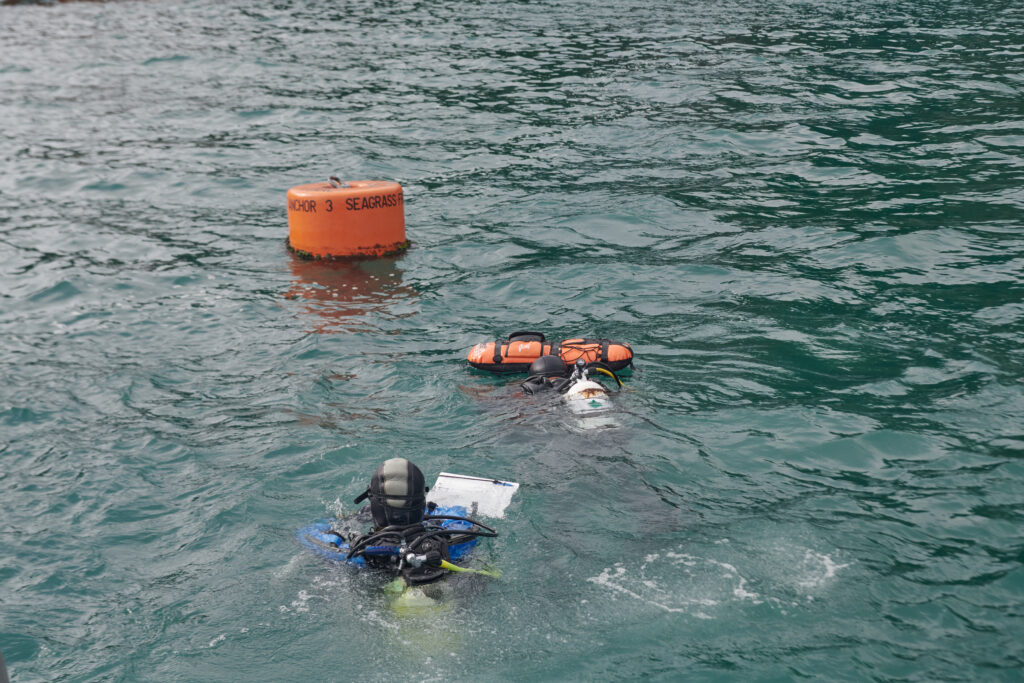

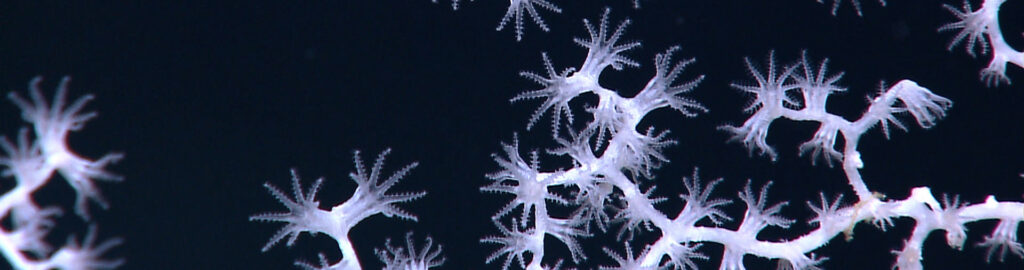

This is a difficult question to answer on a personal basis, because the best way to record changes in the extent or condition of a particular habitat, community or site, is to visit it regularly – not so easy when diving is involved. Additionally, the extent of natural and cyclical changes in marine communities is less well understood than for many terrestrial situations. At particular sites over the years we have both observed increases in the variety and abundance of non-native species, and loss and destruction of long-lived species and habitats such as kelp and maerl. Tracking significant changes (whether good or bad) requires effective monitoring, something that is particularly important within Marine Protected Areas. A clearly visible and positive change from when we both started diving, is the increase in citizen scientist divers; many more eyes out there making records.

As marine biologists with decades of academic experience, which marine developments did you foresee when you started your careers, and which have surprised you the most?

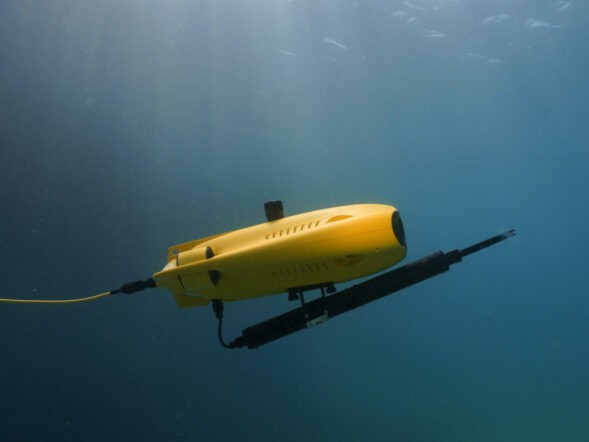

Starting out with cumbersome and uncomfortable diving equipment and unwieldy cameras (our first underwater photography flashguns used bulbs that had to be changed after every shot) we sincerely hoped that things would become easier – as they have – dramatically.

Advances in GPS technology have been hugely helpful, but the rapidity with which it has evolved has indeed been surprising. It has proved really helpful for marine scientists, and for the fishing industry, but in the latter case perhaps too helpful in finding and catching large numbers of fish.

How has photography influenced your work in marine biology and conservation?

Underwater photography can be extremely effective in both gathering information and spreading the word about species and habitats that are largely hidden from view. It is also an effective memory aid as making written notes underwater is never easy. On a specific scale, we find the increasing use of digital photography, including by ‘citizen scientists’ both above and below water, to recognise and track individual animals (from small fish to seals and whales), very exciting. Talking of showcasing a hidden world, we were very grateful for the additional images kindly provided by some award-winning underwater photographers.

What do you see as the most effective ways to get people more involved and aware of the state of marine life?

It starts by showing people what is there through images and information about just what is in that hidden world, as we hope we have achieved with this book. In today’s world, social media is another powerful tool. We think that ‘stories’ about the fascinating and astonishingly complex behaviour of marine animals are particularly good at drawing people into that world. However, as zoologists and photographers, we are a little biased! We also hope that the new natural history GCSE due to be introduced in schools, will include a significant marine element to it. After all, around two thirds of the planet is covered by ocean.

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are often established to conserve biodiversity. In your experience, do they deliver real improvements, or are they more symbolic?

They should deliver real improvements, but too many are still ‘paper parks’ with inadequate protection in force. Progress is being made but it is painfully slow, as we describe in Chapter 12 of the book.

Which marine areas around the British Isles do you find particularly interesting, and why?

Ooh so many!

Frances: the Hebridean islands off the west coast of Scotland, which provided many early diving adventures and meetings with so many then new and unfamiliar species (and new whiskeys!); the Isle of Man where I learnt to dive, gained insight into the colourful lives of British wrasses and met ‘Donald the Dolphin’.

Paul: the vibrant and easily observed shallow reef communities of Devon and Cornwall, the Scottish sea lochs and the North Norfolk chalk reef are my particular favourites.

Have you observed examples in our coastal seas of wildlife adapting to human activity, such as fishing, pollution or habitat alteration? If so, what are some of the most striking or surprising adaptations you’ve encountered?

As in the terrestrial environment, there are animals that can and will adapt and flourish, and many others that cannot. On land, foxes have taken to urban living and peregrine falcons use cathedral heights as substitute cliff faces. Ocean residents have far less experience of living alongside us humans, but we have seen some interesting interactions: butterfly blennies and other small fishes living and guarding their eggs inside discarded glass bottles and tin cans; sea urchins and spider crabs decorating themselves with ‘hats’ of plastic and other debris; lone male dolphins ‘befriending’ swimmers and divers; and of course seabirds following fishing boats waiting for discarded catches.

You discuss the “shifting baseline syndrome” and how human activities like trawling and dredging have altered marine habitats. What are some of the most concerning changes you’ve witnessed in your careers, and how can individuals help mitigate these impacts?

For decades it has proved extremely difficult to film the habitat destruction caused by commercial seabed trawls and this is something that neither of us has witnessed firsthand, even in a scientific trawling context. This year (2025) has shown the damage up for what it truly is, through ‘Ocean’ – a technically challenging, high-resolution film with David Attenborough. In most places it is impossible to know what seabed communities were like before they were ever trawled – hence the “shifting baseline syndrome” and so the long-term changes are likely to be even more stark than those we see today. What can individuals do? At least question where and how your seafood has been caught (read supermarket labels and press for better information) and support local sustainable fisheries. Support organisations such as WWF, Wildlife Trusts and the Marine Conservation Society who can apply political clout. Encourage and arm the next generation with information (good as well as bad).

While marine habitats have largely remained “wild” compared to terrestrial environments, you mention small restoration projects like kelp and seagrass planting. Could you highlight any successful conservation initiatives you find particularly inspiring?

While habitat restoration can be extremely valuable in the right places and at the right times, recovery and conservation in the sea often means simply stopping damaging activities and letting nature ‘do its thing’. Three inspiring examples of that are Lyme Bay (ambitious co-operation between many partners), Lundy (excellent co-working with local fishers) and Arran (community involvement).

For someone new to snorkelling or diving around the British Isles, what’s one piece of advice you’d give to help them connect with and appreciate the marine environment?

Be patient! Wait for the best conditions, and once you are there, move slowly along rather than necessarily trying to cover a lot of ground (so choose a like-minded diving buddy). Animals will be less disturbed and you will be amazed at what you see! In summary stop, look and listen – and practise your buoyancy control.

In a time of over-exploitation of the marine world, how can we change the public mindset toward more sustainable practices?

It’s about showing people what’s been lost, but also what is still there to save, so striking the right balance between some of the shocking facts and figures while avoiding ‘doom and gloom’. A personal plea from us here is to show the recent David Attenborough ‘Ocean’ film (that we have already mentioned), on national free-to-view TV! Perhaps, most of all, we need to stress how everyone will gain from implementing sustainable practices, including industries and those with no involvement with the sea – it’s not just a plea from conservationists.

What can we, as consumers, do with an eye on marine conservation?

Quite a lot, but one of the most important is to make sure that any seafood we buy is sustainably caught (or grown). It’s a difficult issue with varying opinions, but there is good information out there (such as from the Marine Conservation Society and the similarly acronymed Marine Stewardship Council) and we’d say ‘if in doubt, don’t buy’. The latter should apply similarly to ‘single use’ holiday items such as plastic buckets and spades often discarded. Every conversation with shop or restaurant staff, with friends and family (and even local politicians) will help spread the message.

Looking ahead, what gives you hope for the future of marine biodiversity in the British Isles, and what are the biggest challenges we need to address?

The evident ability of natural systems to ‘bounce back’ when we let them has been clearly demonstrated by wonderful examples such as Lyme Bay and Arran that we’ve already mentioned. However these are just small areas and we mustn’t let these successes make us blasé – further damage to habitats and over-fishing continues apace. It remains a huge challenge to get governments to act on scientific advice, but on the positive side there is the ever-growing number of people, both within conservation organisations and independently, professional and unpaid, who are passionate about ‘spreading the word’ about marine biodiversity and making a genuine difference. Best of all, many of them are very much younger than us!

Coastal Seas is available as a limited edition signed hardback book, while stocks last, from NHBS here.

Other titles by Frances Dipper can be found here.

Other titles by Paul Naylor can be found here.

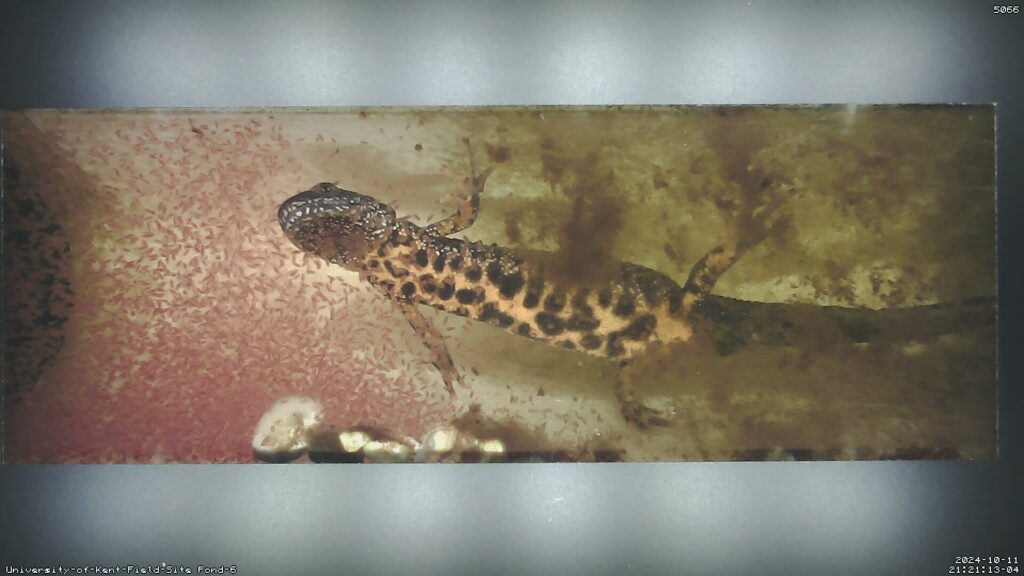

The Riverfly Partnership is a collaborative effort between anglers, conservationists, scientists, and water managers to protect the health and quality of our rivers. They use citizen science to monitor riverfly populations, which are sensitive indicators of water quality, and gather data on these fascinating insects to contribute to a better understanding of river ecosystems.

The Riverfly Partnership is a collaborative effort between anglers, conservationists, scientists, and water managers to protect the health and quality of our rivers. They use citizen science to monitor riverfly populations, which are sensitive indicators of water quality, and gather data on these fascinating insects to contribute to a better understanding of river ecosystems.

In 1993,

In 1993,

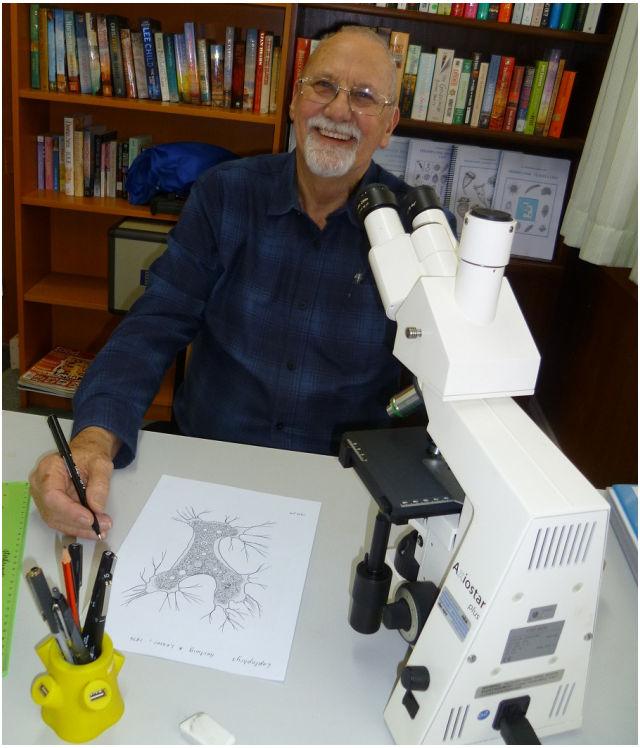

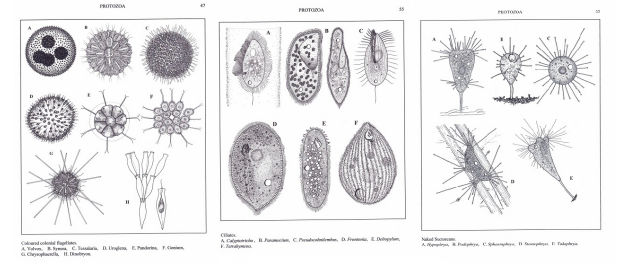

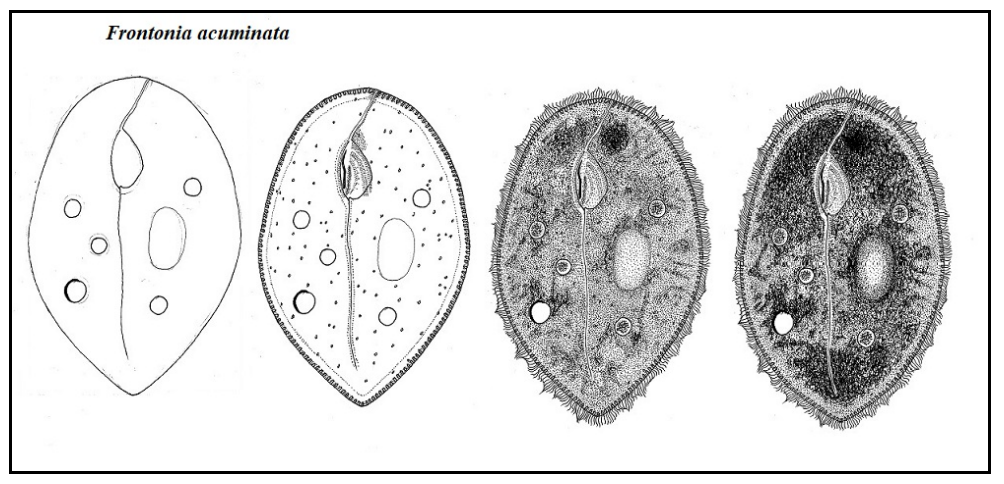

My basic field kit apart from my wellington or gumboots, comprises a 30µm plankton net as seen in this photo, a basting pipette for mud surface collection, several numbered, wide

My basic field kit apart from my wellington or gumboots, comprises a 30µm plankton net as seen in this photo, a basting pipette for mud surface collection, several numbered, wide