Neil Middleton is the owner of BatAbility Courses & Tuition, a training organisation that delivers bat-related skills development to customers throughout the UK and beyond. He has studied bats for over 25 years with a particular focus on their acoustic behaviour. Neil is the lead author of the popular Social Calls of the Bats of Britain and Ireland (2014) and in 2016 he wrote The Effective Ecologist which tackles the challenges facing ecologists as they endeavour to perform to the highest standard within their working environment.

Neil Middleton is the owner of BatAbility Courses & Tuition, a training organisation that delivers bat-related skills development to customers throughout the UK and beyond. He has studied bats for over 25 years with a particular focus on their acoustic behaviour. Neil is the lead author of the popular Social Calls of the Bats of Britain and Ireland (2014) and in 2016 he wrote The Effective Ecologist which tackles the challenges facing ecologists as they endeavour to perform to the highest standard within their working environment.

His latest book, Is That a Bat?, published in January, provides a technical, yet accessible, guide to understanding and categorising non-bat sounds. Including a downloadable audio library, this ground-breaking book is designed to help bat workers be more confident in analysing their recordings, and also discusses the wider conservation benefits of studying non-bat sounds.

We recently caught up with Neil to chat about the book and about nocturnal sounds and their analysis.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Where did the idea for this book come from? And do you feel that this is a subject/area of study which has been largely overlooked?

The idea came from a number of different directions during the years prior to my starting work on this project. As someone doing lots of sound analysis for bats and also seeing the kind of queries that would get sent to me, it was apparent that bat workers spent at least some time, unproductively, trying to work out what species of bat it was, when it turned out not to be a bat at all.

Additionally, whilst working in darkness we often hear other sounds that get ignored or written off as ‘of no interest’. These sounds (eg a Schedule 1 bird species) could actually be very relevant to the project we are working on and the reason why ecologists are being sent to a site in the first place. Saying ‘I don’t know. It’s not a bat, so it doesn’t matter’ isn’t really the best approach to take. When people see something, they tend to react more positively, as opposed to when they hear an unfamiliar sound. In darkness, however, sound is usually all you get. So, this put ‘in the frame’ the thoughts I had regarding audible sound encountered during darkness.

Finally, I had been asked many times over the years, questions such as, ‘do mice make high frequency sounds?’ Until relatively recently I didn’t have a proper answer to that question and probably, to be honest, didn’t even think that I cared or that it mattered when it came to doing bat work. I could not have been more wrong. Not only mice, but all of our small terrestrial mammals make ultrasonic sounds that can get picked up by bat detectors, and many produce sounds that are quite similar to some of the echolocation pulses or social calls produced by bats.

Having written this book (and completed the immense amount of research that it has inevitably involved) do you now find yourself looking at and treating your own recorded data differently?

Having written this book (and completed the immense amount of research that it has inevitably involved) do you now find yourself looking at and treating your own recorded data differently?

Oh yes, most definitely. I am now very nervous about being certain about anything slightly unusual. When I deliver presentations, I often use the expression, ‘You only know what you know’. I feel this underpins my whole thought process now, as it also follows therefore that ‘You don’t know what you don’t know, and how much there is still to find out’. I honestly think, in some respects, we are only scratching the surface when it comes to our knowledge of bat-related sound, as well as all of the other species and things that make noise within a bat’s soundscape. I think we are sometimes far too sure of ourselves for our own good.

Following on from that, it also has consequences to our, sometimes misguided, reliance on automated classifiers. I get quite unsettled when I hear some people talking about complex stuff (eg separating Myotis species with high degrees of confidence) in such an authoritative manner. I have always preferred a more cautious approach, and even more so now. If anything, having now done this project, I would say that I have backtracked, in some respects quite far, from stuff that I once thought I knew reasonably well.

How do you feel about auto-ID software? Do you have concerns that it gives users a false sense of confidence in their results? And do you feel that, as technology becomes more advanced, it might be at the expense of expertise in both fieldcraft and analysis?

To answer the last part of this question first, yes on both accounts. I go into quite a lot of detail within the book as to why I think this way. The pages in the book regarding these areas were written and revisited many times during the process. When I look at my first draft of those pages (which I still have) it is interesting for me to see the journey I have been on and how my thinking changed during the process.

My viewpoint on automated classifiers at the start was quite negative in all respects. In some respects, the classifier challenge isn’t related purely to bats. If only it was, it would be so much easier. I was horrified to find classifiers confidently identifying lots of non-bat-related sounds as bats. This was the point for me where this work moved well into the ‘essential reading for bat workers’ category, as opposed to a ‘nice to know’. I remember that day extremely well. I was in a hotel room, near Gatwick, doing analysis of harvest mouse calls. They looked a bit like common pipistrelles, and the three classifiers I used that day all agreed! After publication, I was especially pleased to see that some of the reviews have very much labelled it as ‘essential reading’, for a number of reasons (ie not just the scenario discussed here).

But putting all that aside, for the moment, my final conclusion (for the time being?) is that there are definitely better classifiers than others, and there are different ways in which classifiers do things that will produce different results. I also feel that classifiers used sensibly, by experienced people (ie those who possess all the ‘essential’ knowledge), with audits in place, can be extremely powerful and useful. However, just like a human, a classifier has got so many things loaded against it arriving at the right answer (much of which is discussed in the book). So, it is fair to say that classifiers can come up with completely wrong answers. It is also fair to say that humans, even with experience, can also come up with completely wrong answers.

Therefore, neither approach is perfect, but the thing I now feel strongest about isn’t the classifiers themselves but, firstly, the lack of training people get in understanding how these systems work ‘behind the scenes’. And secondly, the lack of technical knowledge and experience of bat-related acoustics demonstrated by some of those who use these systems. I think it is too easy for organisations to give this important and often complicated work to junior members of the team, furnishing them with classifiers etc. It is then as easy for an inexperienced person to use these systems, write reports and influence decisions that are being made, without they themselves (or their bosses) appreciating that perhaps they or the classifier is getting it wrong (back to ‘You only know what you know’). Ultimately, during any project, the human decides (or at least they should). They decide what classifier to use. They decide the methods to use. They decide to blindly accept what the system is telling them, or not. They decide to do a proper manual audit of the results, or not. They decide what goes into a report and whether or not to be cautious with their interpretation. In the book I say something along the following lines:

‘Our bat detectors and associated software should be regarded as educated idiots. Very intelligent, but on occasions totally lacking any common sense. There is one part of the process, however, where ‘common sense’ needs to be applied. This is the part where a human decides what to do next. You need to keep pressing that ‘Common Sense’ button before jumping in with wrong conclusions and inappropriate decisions.’

Too many people blame a classifier for making mistakes, when in fact we should perhaps be collectively looking in the mirror. It is a tool, and like any tool there are right ways and wrong ways, right times and wrong times, to use it. ‘It’s a bad workman who blames his tools’. I think if you use a good classifier appropriately, and the methods/results are audited by an experienced person, the combination of the two, each allowing for the other’s weaknesses, can work well.

Do you think that increased awareness of the other noises recorded during bat surveys has wider implications for conservation? For example, can you provide us with a situation where bat survey recordings might be useful for other species/purposes?

Do you think that increased awareness of the other noises recorded during bat surveys has wider implications for conservation? For example, can you provide us with a situation where bat survey recordings might be useful for other species/purposes?

Definitely. This is one of the main threads within this work and the examples are numerous. We live in a country which, relatively speaking, isn’t that diverse when it comes to night-time species (bats, other mammals, birds, insects…). But even in the British Isles we have bush crickets, moths, birds, shrews, voles etc that can all be identified either audibly or from the analysis of bat detector recordings. Now take this approach into more diverse parts of the world. We haven’t really begun to scratch many of the surfaces, as far as I can tell. Even just looking at the UK, I don’t believe for one second that ‘Is That A Bat?’ is anywhere close to the total picture of what we may encounter acoustically during darkness. There is so much more to find out and this knowledge will almost certainly lead to better decision making and associated benefits for conservation.

Bat survey technology is constantly progressing, and there is a lot of recording equipment and analysis software on the market. It’s not surprising that it can be confusing for even the most experienced ecologist. What advice would you give to an aspiring bat worker who wants to gain experience and skill?

Listen and learn from lots of different experienced people. Take all of their thoughts and blend these with your own developing technical knowledge and experience. Understanding how bat echolocation works and how this links to behaviour is an essential foundation that should be in place before someone begins to attempt to identify bat calls to a species or group level. For example, the answer is often as much to do with where a bat is (relative to surroundings), as it is to do with what a bat is.

Be wary of anyone who tells you they can identify every bat call, or that the system they use is always right. Don’t be afraid to just call it what you know it is (eg Myotis), as opposed to trying to always get it diagnostically to species level (eg it’s a whiskered bat). In any case, for some jobs you won’t need to know the precise species on every occasion. Why risk your credibility when there is no reason to do so. When you start appreciating the reasons why you can’t identify every bat, you are beginning to become an experienced and respected bat worker. People who don’t really understand this subject are afraid not to identify everything. People who really understand this subject know that everything can’t be identified (not at this stage anyway!).

What was the most interesting, bizarre or unexpected non-bat sound you came across during the research and writing of this book?

I think my favourite is the Long-Eared Owl juvenile call, when slowed down 10 times. This is something many bat workers do with bat calls in order to make them audible, and with an unusual recording it might be how you would first listen to it before realising that it’s not a bat. It still makes me smile, for no scientific reason whatsoever. It just reminds me of ‘Casey Jones & The Cannonball Express’ (the whistle from his steam engine). I know some of your younger readers will need to Google ‘Casey Jones’.

Finally – a question we ask all our authors – what is next for you? Do you have plans for further books?

Yes, two others. But I am scared to say too much at the moment for a number of reasons, including that once you say out loud what you are doing, the pressure is then piled on to get it done. I am just recovering from this one! So, I need some time to carefully consider which of the two ideas comes next and how to marry up the huge amount of time it takes to produce a book with other commitments.

…………………………………………………………………………………………….

Also by Neil Middleton:

Social Calls of the Bats of Britain and Ireland

Social Calls of the Bats of Britain and Ireland

#212405

Brings together the current state of knowledge of social calls relating to the bat species occurring within Britain and Ireland, with some additional examples from species represented elsewhere in Europe. Includes access to a downloadable library of calls to be used in conjunction with the book.

The Effective Ecologist

The Effective Ecologist

#226648

The Effective Ecologist shows you how to be more effective in your role, providing you with the skills and effective behaviours within the workplace that will enable your development as an ecologist. It explains what it means to be effective in the workplace and describes positive behaviours and how they can be adopted.

• Spanish language added.

• Spanish language added.

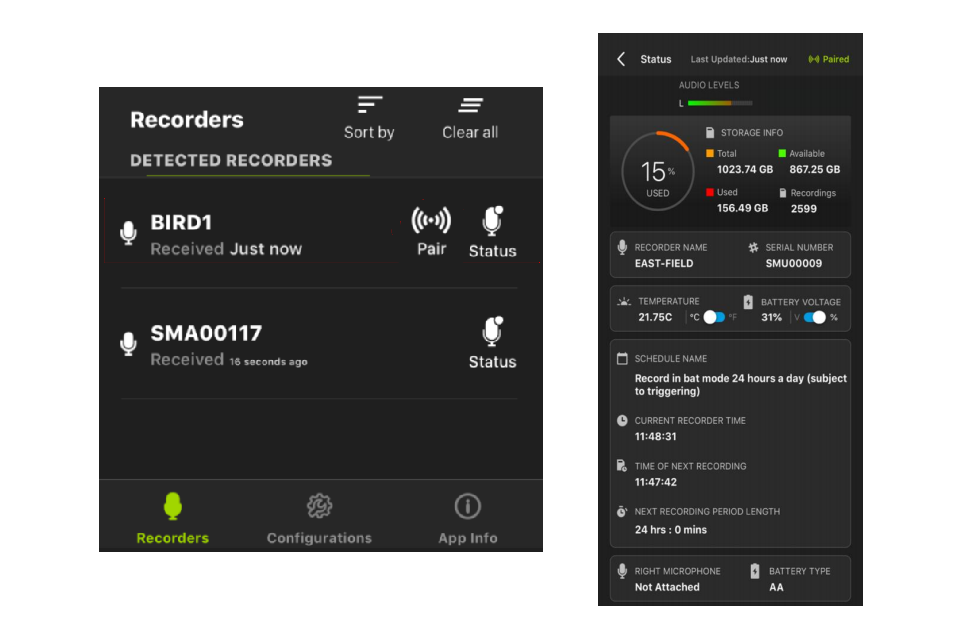

The Video Endoscope camera is IP67 water resistant so we wanted to test its performance when recording underwater. It also has adjustable LED brightness so we wanted to test it in dark conditions. We chose a pond on a farm in West Dorset known to have some tadpoles and selected some nest boxes in a nearby area to examine for nesting activity. We used a 16GB microSD card and 4 x new AA alkaline batteries.

The Video Endoscope camera is IP67 water resistant so we wanted to test its performance when recording underwater. It also has adjustable LED brightness so we wanted to test it in dark conditions. We chose a pond on a farm in West Dorset known to have some tadpoles and selected some nest boxes in a nearby area to examine for nesting activity. We used a 16GB microSD card and 4 x new AA alkaline batteries.

Tim Dee is a naturalist, radio producer, and author of

Tim Dee is a naturalist, radio producer, and author of

By travelling north you poetically write about the birds that come and go; from observing redstarts in Lake Lagano, Ethiopia, to enjoying the dawn chorus in a reedbed in Somerset. What can be learned from birds in migration, and how is migration changing for them?

By travelling north you poetically write about the birds that come and go; from observing redstarts in Lake Lagano, Ethiopia, to enjoying the dawn chorus in a reedbed in Somerset. What can be learned from birds in migration, and how is migration changing for them?