In 2018 , while still running a taxi business, an opportunity arose to purchase a few acres of local woodland on the edge of Dartmoor in Devon. Completed within a matter of weeks, Steve and Tamara Davey became proud custodians of their very own woodland!

When they discovered an impressive range of wildlife on their woodland site, they decided that the management of the area would be based on the continued provision of habitat for certain species, including seven recorded bat species, the visiting Nightjar and Woodcock.

We caught up with Steve to ask him about how they are supporting nature through their project Woodland Wildlife.

Can you tell me a little about your backgrounds.

Both Tamara and myself had childhood holidays in the Scottish Highlands as children, and there is no better place to develop an affinity with nature. It’s a place that holds a permanent residency within our hearts, those childhood memories imprinted on our futures. Mine were on the West Coast of Scotland opposite the Isle Of Skye. We used to stay in these old caravans that leaked and were powered by calor gas. The smell of the matches and gas appliances echoes those memories for me. The area was only a few miles up the coast from where Gavin Maxwell wrote his best-selling book Ring of Bright Water. As a family we spent a lot of time down at Sandaig ( in the book it was Camusfearna), Gavin’s books were really the only ones I read due to my interest in nature and love for Scotland. Above his hearth he had inscribed in Latin the words “non fatuum huc persecutus ignem” meaning, “it is no will o the wisp that I have followed here.” This phrase is very apt and resonates with our Woodland Wildlife project.

Aside from Scotland both Tamara’s and my childhoods involved getting out in nature with family walks, especially on Dartmoor. Also, similar to the book and film Kes, aged twelve I had a female kestrel to look after. My father converted the garden shed, and I remember rushing home from school every day. We looked after a tawny owl for a while too. Myself and our son also volunteered at a local bird of prey centre – these memories, and the knowledge you gain from an early age all lie dormant until the right opportunity presents itself later in life.

What motivated you to embark on the Woodland Wildlife project?

From the Spring of 2018 we made regular trips to the woodland because we couldn’t keep away and used to come up with loads of excuses to the selling agent on why we were visiting so often. We completed the purchase at the end of the summer. During the first twelve months we were staggered by the volume and diversity of the wildlife within our little plot and it was this that spurred us into creating Woodland Wildlife. I couldn’t believe that the domain woodlandwildlife.co.uk was available so I snapped it up. I then asked the web company that had recently rebuilt my taxi website to work on a website for Woodland Wildlife. They came up with the current logo which I really liked however the squirrel was grey and so I asked them to change it to red as that signified hope to me! At that point the future focus was more on the development of guided visits. In August last year we set up the Facebook page and that is seeing a steady increase of followers. We post on there most days and this time of year we may be posting up to eight times in one day, purely because of the observations – we are always finding new species to photograph. Through the winter months the posts are more project focused as that is the time of the year when most of the manual work is done.

What has been the biggest challenge in returning the woodland back to nature?

The nature was already there, nothing has needed returning as far as we are aware. But with small sized plots sensitive management is vital, for instance; if you don’t manage that important grassy ride, over time succession will take hold and that habitat (in our case) would be overrun with bramble and bracken, therefore the grasses would die off and displacement of species will happen. Our grassy rides are alive with insect life and as far as we are concerned these areas are a priority within our plot. When you see how small an area our grassy rides are and you see how many species they are supporting such as: leaf hoppers, beetles, bees, hoverflies, moths, grasshoppers, crickets, butterflies you can then understand how vitally important these small areas are. I would say our biggest challenge is still ahead of us. In 2012 the main plot was clear felled and in 2013 the holding company planted over 2000 young sitka spruce trees. These are now over eight years old and growing rapidly in amongst the birch, sweet chestnut, beech and a few other species. Being on an easterly facing slope (after all it is Devon) we are giving careful consideration to future extraction of timber and to what extent the damage would be. We are mindful not to ruin everything that we have done over the years. so the plan will be (in conjunction with the Forestry Commission) to convert over to native woodland. We will still retain some sitka for the goldcrests and siskins, but these will be in the area towards the top of the plot, whereby future extraction damage will be minimal.

Sitka are awful trees to work on as they are very prickly to handle. Even though they are only young it’s incredibly hard work felling them and dragging them around to produce dead hedging. Our adjoining plot is a mature stand of Douglas fir of 3.5 acres and that has recently been thinned. The remaining stems will grow on for a further 5 to 10 years, with the extra light they will grow in girth and not height. We have tagged a random 30 stems and will monitor their growth rate annually. This is one commercial aspect to our project, we plan to nurture a healthy self seeded understory within this stand and re plant where necessary in the future when it’s felled.

Was there a particular plant or animal that you wished to see return to the woodland?

Yes, the nightjar, they are in the area this season which is great, last summer they were on our plot and we regularly saw two of them. Having your own woodland is one thing but having nightjar in your woodland is a priceless dream. We spent many summer evenings there watching them, calling them in with a recording of their call (yes that works). On a couple of occasions early in the nightjar season, June I think, they landed in front of us on a tubex shelter, attracted to anything white due to the males having white markings on their wing and tails. Our sleepy dogs got their attention and flew in to check us out. The video is on the website, it’s not brilliant as it was recorded on my phone, but a wonderful experience nonetheless. We observed them through to the end of July and on each occasion the sightings consisted of a brief checking us out and churring away like they do. A truly amazing bird that due to its nocturnal habits has not been an easy species to study. They like young plantations up to approximately ten years of age as after that the canopy has closed in. They also like birch and sweet chestnut, both of which we have in abundance. We are coppicing the sweet chestnut which will give a more diverse structure to the woodland and also has many benefits to other wildlife as well as giving longevity to the tree itself. The nightjars arrive in May and have normally disappeared by the end of August and sometimes into September. Once the young have fledged they will migrate. Our thinning works of the Douglas fir overran into May and we are certain that that level of disturbance (the sound and vibration of over 200 mature fir being felled) made them look elsewhere for a suitable nest site for this season. High hopes for next year!

In what ways can you draw an income from the project and how do you ensure that those ways are sustainable?

Part of the plot is mature Douglas fir, so over the years there will be an income from the felling of those but there also comes obligation and costs to re-plant. This area is 3.5 acres and we are hoping that at least 20% of that area will self-seed and will therefore not need re-planting. After 14 years of running a taxi company we have decided to pass it on to someone else as we want to concentrate on our woodland which will also involve craft sales. We plan to sell at an occasional local market, selling wooden products such as pendants, necklaces, key rings, hand made cards, Christmas decorations and fairy houses. All of the wood used will be from the bi product of our habitat work and therefore very sustainable. We are not skilled wood turners, I would describe our woody crafts as rustic. We also hope to offer guided visits for small groups of people who either want to immerse themselves into an incredibly diverse 8 acre plot of woodland that doesn’t have any public access( that’s called forest bathing nowadays), or groups and individuals that would like to visit to look at our management practises, it could also be for specialist groups to study bats, birds, butterflies etc. Although the craft sales will be necessary we do hope that the tours can be a success too as we will have great pleasure in sharing this unique place in South Devon.

What would you say has been the project’s biggest success story so far?

This has to be the three small wildlife ponds created in the spring of last year. Our philosophy has always been that our work creates a biodiversity gain. The ponds are a totally new feature to the wood and therefore a totally new habitat with the nearest water course being in the bottom of the valley.

The ponds are host to pond skaters, diving beetles, water boatmen, frogs, toads and a few species of dragonfly. The mosquito larvae they produce is a food source for the seven recorded species of bats that we have there. The frogspawn and toadspawn this year was amazing. This is boosting the sites biodiversity and that feels great. The Devon Wildlife Trust’s, Batworks Grant, helped with the costs of the ponds which was very welcome indeed, because so far we have funded all the costs ourselves. The top pond was also designed with a very shallow gradient at one end so that any feeding nightjar can swoop in and get a drink on the wing.

The other success is our plantings, since Nov 2018 we have planted over 400 additional trees, shrubs and hedging. From scots pine to broad leaved privet, all-in-all over 20 new species have been planted. The hedging area consists of field maple, hazel, dog rose, dog wood, crab apple, blackthorn and hawthorn, and is growing well, albeit slowly. Once mature this will provide an incredible food source and habitat for many species. We also sought advice from a consultant ecologist on behalf of Butterfly Conservation, they recommended planting broad leaved privet, wild privet and alder buckthorn all of which will provide a valuable food source for many species of butterflies, insects and moths. The alder buckthorn being the food plant for the brimstone butterfly caterpillar.

Can you offer any advice to anybody wanting to undertake a similar project?

There is a misconception that when you purchase some woodland in the UK that you are legally bound to manage your plot, but this is not the case. Currently you can do as much or as little as you want, there are legalities regarding volume of timber that you are allowed to cut down, and rightly so. Personally speaking I think there should be some sort of stewardship course involved with any woodland purchase, but generally speaking people who buy woodland do have the environments best interests at heart. Neither myself nor Tamara are formally qualified in land management or woodland management, but what we do have in bucket loads is the passion, and when it is your passion you absorb information like a sponge. If you are interested in purchasing some woodland please make sure you do a lot of reading up first, SWOG ( small woodland owners group) is a great resource. Think about things like how far are you willing to travel to get to your woodland, our journey takes 25 minutes but I know of some owners who live a couple of hours away and then that restricts those little journeys when you just want to go there for an hour or two. Think about public access and rights of way, access, species of trees on site, how neglected the woodland is because that may dictate how much physical work maybe required. I know owners that have a couple of acres of plantation and therefore their management work is negligible. Think about orientation, diversity and age of species and the potential value of the timber there. Getting a flat site is not easy and virtually impossible in Devon, some come with streams etc. You would need to appoint a solicitor as the conveyancing is similar to house buying but much more straight forward.

We would say to anyone interested in purchasing some woodland to definitely do it, it is an amazing thing to do, yes we can buy fancy cars and gadgets and go on expensive holidays but owning your own little piece of nature is a priceless thing to do. It’s more like guardianship than ownership, but you will have a lot of control over the future of that plot.

Love nature, it will never fail you.

Do you have any long-term plans for the future of Woodland Wildlife?

Well where do we start here? If money was no object we would like to deer fence large parts of our woodland to allow natural regeneration to occur unhindered. But money is an object so we will improvise and mitigate the grazing as much as possible. Luckily we are not overrun with roe deer but there are a few around. The damage they do to new growth is staggering.

Over time we would like to see part of our main plot restored back to its natural former state which was wooded heath. Around 1800 the wider woodland was mapped as a Down which would correspond with our small patches of heather and large amounts of gorse and bracken. Dry lowland heathland is a scarce habitat these days and we would like to re-nature that habitat along with keeping the coppiced sweet chestnut, birch and beech. The plan will be for the main plot to remain an open woodland with pockets of heath and grassy rides. We will keep some sitka on the higher parts of the plot.

This winter will involve widening the lower part of the North to South ride which is quite overgrown, creating a ride that will traverse the contours from the West to East ride. This will involve the felling of a lot more young sitka but it will kick start the project of connecting up some of our micro habitats. We are keen to provide a suitable site for the migrating nightjar and the wintering woodcock and this will involve a lot of physical work. Any major works such as this needs careful consideration for the future resilience of the woodland. All of our plantings have been carefully selected with the future in mind for example, the scots pine (although slow growing) is a fantastic tree that supports a large amount of wildlife plus once established will cope well with periods of dry weather. We have also planted some juniper and these trees will also cope admirably in dryer conditions and therefore the challenges of climate change. The naturalised species such as birch, beech, gorse, heather, bramble and bracken will naturally cope with dryer summers.

With regards to Woodland Wildlife as a business, we hope that the occasional small group or individual will continue to visit to experience this magnificent site. We aim to continue with the craft sales into the future. We aim to continue to document our species and our works. The emphasis will be on small groups as we are keen to prevent compaction of soils.

All photographs courtesy of Woodland Wildlife © Woodland Wildlife

Woodland Wildlife

To find out more about Steve and Tamara’s fascinating project you can follow them on facebook and visit their website

Further Reading on managing woodlands for wildlife and people.

Managing Your Woodland for Wildlife

Managing Your Woodland for Wildlife

By: David Blakesley, Peter Buckley and Tharada Blakesley

Paperback| May 2016| £12.99

From conserving deadwood to putting up bat boxes: this book will appeal to small woodland owners wishing to improve woodland for wildlife.

Woodland Creation for Wildlife and People in a Changing Climate: Principles and Practice

Woodland Creation for Wildlife and People in a Changing Climate: Principles and Practice

By: David Blakesley and Peter Buckley

Paperback | July 2010| £5.99 £24.95

This book presents a comprehensive and richly-illustrated guide to the principles and practice of woodland creation for wildlife and people.

A Journey in Landscape Restoration: Carrifran Wildwood and Beyond

A Journey in Landscape Restoration: Carrifran Wildwood and Beyond

Edited by: Philip Ashmole and Myrtle Ashmole

Paperback | June 2020| £16.99 £18.99

An inspirational account of the rewilding of Carrifran Wildwood, showing what can happen when locals take charge of landscape restoration.

The Wood: The Life and Times of Cockshutt Wood

The Wood: The Life and Times of Cockshutt Wood

By: John Lewis-Stempel

Paperback | March 2019| £9.99

A lyrical diary of four years spent managing three and half acres of mixed woodland in south west Herefordshire.

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

Some of the most well-known and respected scientists in history have had an incredibly varied range of interests and passions. Take Darwin, for example, who not only studied plants and animals, but also geology, anthropology, taxidermy and medicine. Do you think that, in modern times, we no longer celebrate or respect the ‘generally curious’ and instead expect people to be much more specialist in their areas of expertise?

Some of the most well-known and respected scientists in history have had an incredibly varied range of interests and passions. Take Darwin, for example, who not only studied plants and animals, but also geology, anthropology, taxidermy and medicine. Do you think that, in modern times, we no longer celebrate or respect the ‘generally curious’ and instead expect people to be much more specialist in their areas of expertise?

Bumblebees: An Introduction

Bumblebees: An Introduction

When and where to go:

When and where to go:

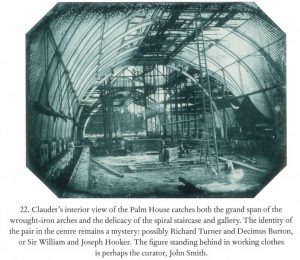

Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today

Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

Why were palms so important to the Victorians?

Why were palms so important to the Victorians? How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?

How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?