The Autumn issue of Conservation Land Management (CLM) covers a variety of themes relevant to those involved in managing land for conservation, from the creation of bare ground habitats to incorporating climate objectives into the management of wildlife sites. Here, Assistant Editor Catherine Mitson provides a summary of the articles featured in this latest issue.

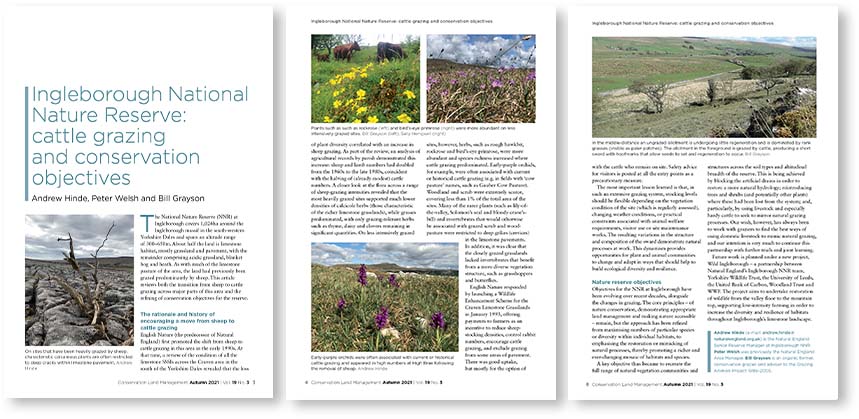

Ingleborough National Nature Reserve (NNR) covers a huge expanse of limestone grassland and pavement, acidic grassland, blanket bog and heath in the south-western Yorkshire Dales. Previously, the land had been grazed by sheep, numbers of which had doubled from the late 1960s to the 1980s while the number of cattle halved. The negative impact of sheep grazing was evident, especially in heavily-grazed areas where grasses dominated, and the only plants remaining in significant numbers were hardy species such as thyme, clovers and daisies. But an opportunity arose to reduce sheep numbers and to promote cattle grazing, and in this article Andrew Hinde, Peter Welsh and Bill Grayson describe the success of the reintroduction of cattle grazing to Ingleborough and outline the NNR’s conservation objectives going forward.

The next article brings us to Havergate Island in the Alde–Ore Estuary SSSI in Suffolk. Since 1997, spoonbills have been trying to colonise the estuary but breeding attempts failed, mainly due to the presence of and predation by foxes. But over on Havergate Island, a more secluded site with little human disturbance, spoonbill numbers were increasing. To encourage breeding on Havergate, RSPB set up elevated nesting platforms and, owing to the presence of foxes and other predators on the island, installed predator-exclusion fences. Vivienne Booth, Aaron Howe and Adam Rowland describe how the predator-exclusion fences were designed and installed, leading to the return of breeding spoonbills to Suffolk.

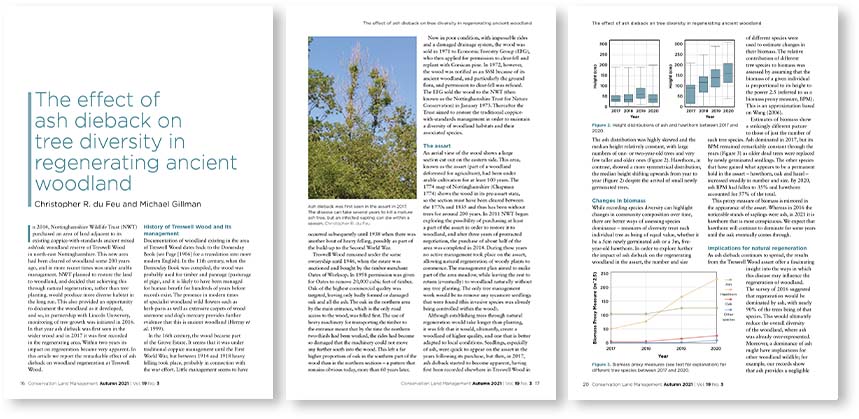

Christopher du Feu and Michael Gillman take us to Treswell Wood in north-east Nottinghamshire. In 2014 Nottinghamshire Wildlife Trust purchased an area of the wood that had previously been cleared for agriculture, known as the assart. Instead of planting trees, it was decided to let nature take its course and leave the assart to return to woodland naturally. Monitoring of woodland regeneration began in 2016, but in 2017 ash dieback struck the assart. In this article the authors report the results of this ongoing monitoring, and demonstrate the remarkable effect that ash dieback has had on natural regeneration.

With COP 26 fast approaching, many of us have noticed increasing news coverage of the climate and biodiversity emergencies. But on nature conservation sites, can climate objectives and biodiversity-related priorities co-exist? Heathlands, for example, are managed by techniques such as burning, a contradictory approach from a climate perspective. John Bacon addresses this dilemma, and takes a look at some initiatives in Shropshire to demonstrate how climate objectives are being incorporated into habitat management, with biodiversity still being the top priority.

The final article encourages us to appreciate the importance of bare ground habitats. Many species of spiders, ground beetles, wasps, bees and reptiles (to name a few) depend on the warm microclimate that bare ground provides for hunting, basking and nesting. Using examples from south Staffordshire, Katie Lloyd describes the process of bare ground creation, including the design, type and size of scrapes; how to maintain and manage newly-created bare patches; mitigation and other considerations to be aware of before undertaking such a project; and the benefits that this overlooked habitat provides.

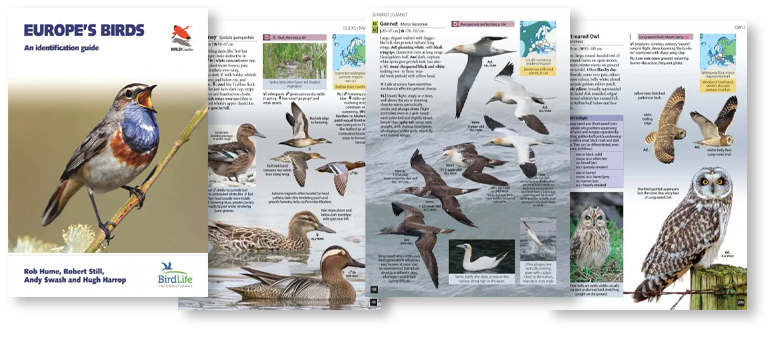

In this and every issue you can expect to see Briefing, keeping you up to date with the latest training courses, events and publications, and On the ground which provides helpful tips or updates on products relevant to land management.

Other features that regularly appear in CLM include Viewpoint, a similar length to our main articles, but here authors can voice their own views on various conservation issues, and Review, which can include letters from readers or updates from our authors.

CLM is published four times a year in March, June, September and December, and is available by subscription only, delivered straight to your door. Subscriptions start from £22 per year. Previous back issues are also available to purchase individually (subject to availability).

If you are involved in a conservation project and think your experiences could be useful to other practitioners, we would love to hear from you. If you are interested in writing for CLM feel free to contact us – we will be happy to discuss your ideas with you.

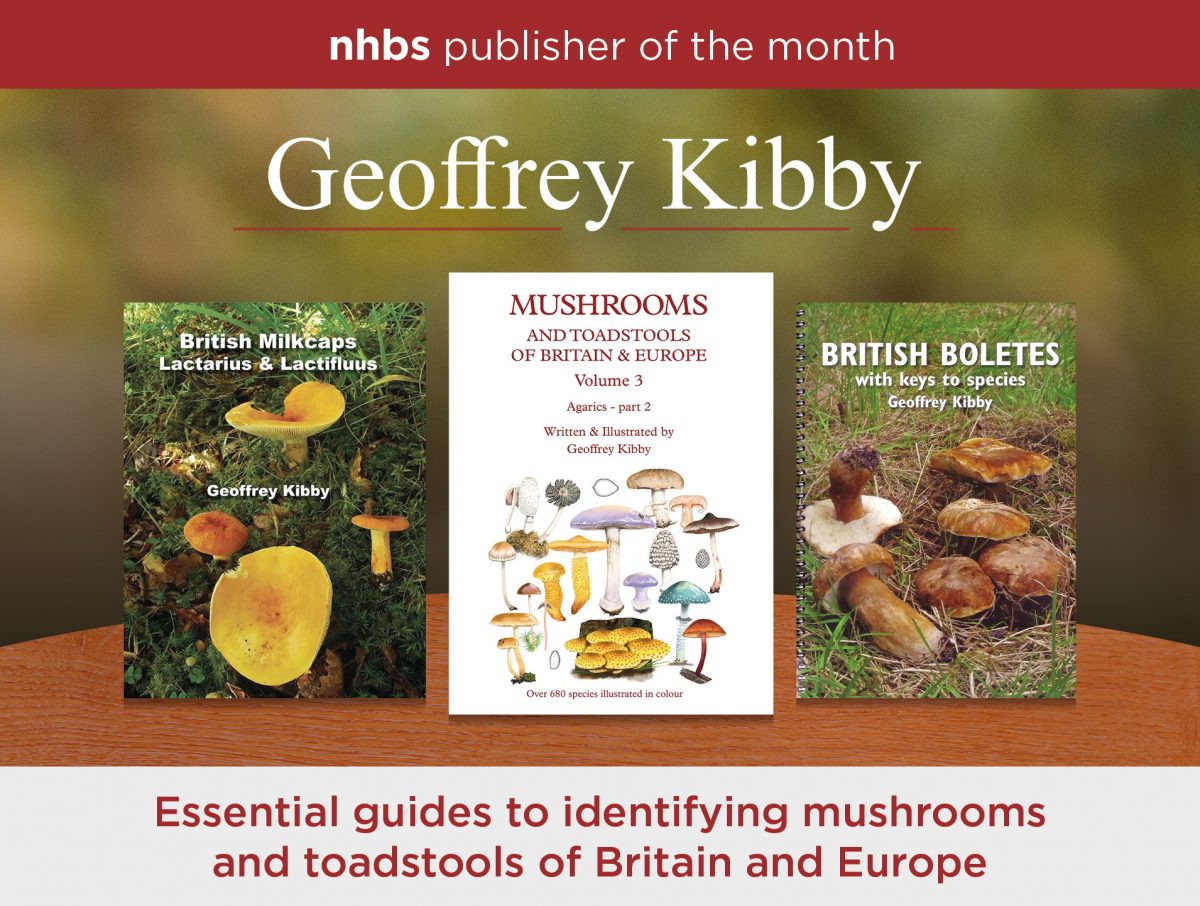

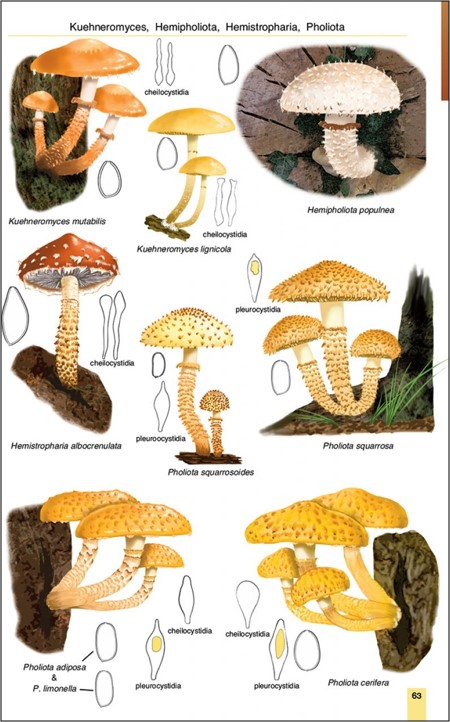

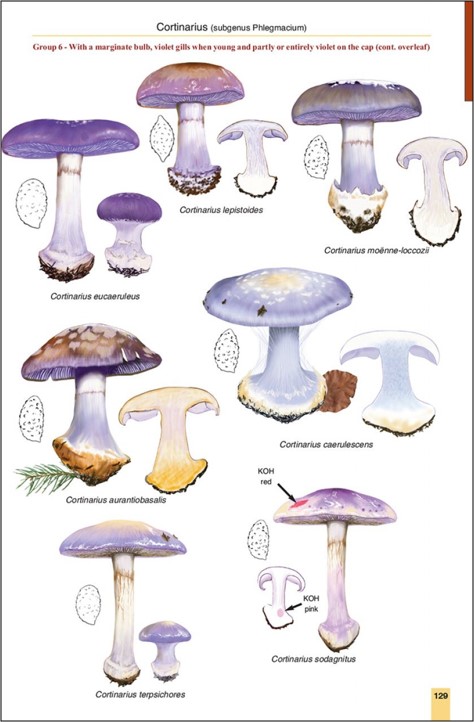

Geoffrey Kibby is one of Britain’s foremost experts on identifying mushrooms in the field, and his privately published books on how to identify British mushrooms pass on many of those skills. Kibby’s user-friendly books contain an enormous amount of information, are fully illustrated and are aimed at everyone, from the fungi enthusiast to the expert mycologist. The wealth of detail includes vital features to look for when identifying wild mushrooms and the important identification characteristics when using a microscope, often an essential tool in mycology.

Geoffrey Kibby is one of Britain’s foremost experts on identifying mushrooms in the field, and his privately published books on how to identify British mushrooms pass on many of those skills. Kibby’s user-friendly books contain an enormous amount of information, are fully illustrated and are aimed at everyone, from the fungi enthusiast to the expert mycologist. The wealth of detail includes vital features to look for when identifying wild mushrooms and the important identification characteristics when using a microscope, often an essential tool in mycology. I was 13 when I first became aware of fungi: an intensely violet toadstool, unlike anything I had ever seen (Laccaria amethystina) and from that moment, I was hooked. I bought my first little mushroom guide, then another and another and more through the years until my bookshelves started to groan under the weight of books about fungi. Now, more than 50 years later, I am writing my own books, trying to produce the sort of works that I would have wanted as an aspiring young mycologist. My books are based on my years in the field, hopefully capturing the essence of each species. I have also made a conscious point of illustrating species not readily available in other guides and trying to give the most up-to-date names in what is an ever-changing science. Mycology is an inexhaustible field of study at whatever level your interest lies. With over 4000 species of larger fungi in Britain, you will never run out of species to find or new facts to discover.

I was 13 when I first became aware of fungi: an intensely violet toadstool, unlike anything I had ever seen (Laccaria amethystina) and from that moment, I was hooked. I bought my first little mushroom guide, then another and another and more through the years until my bookshelves started to groan under the weight of books about fungi. Now, more than 50 years later, I am writing my own books, trying to produce the sort of works that I would have wanted as an aspiring young mycologist. My books are based on my years in the field, hopefully capturing the essence of each species. I have also made a conscious point of illustrating species not readily available in other guides and trying to give the most up-to-date names in what is an ever-changing science. Mycology is an inexhaustible field of study at whatever level your interest lies. With over 4000 species of larger fungi in Britain, you will never run out of species to find or new facts to discover.