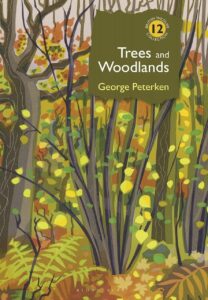

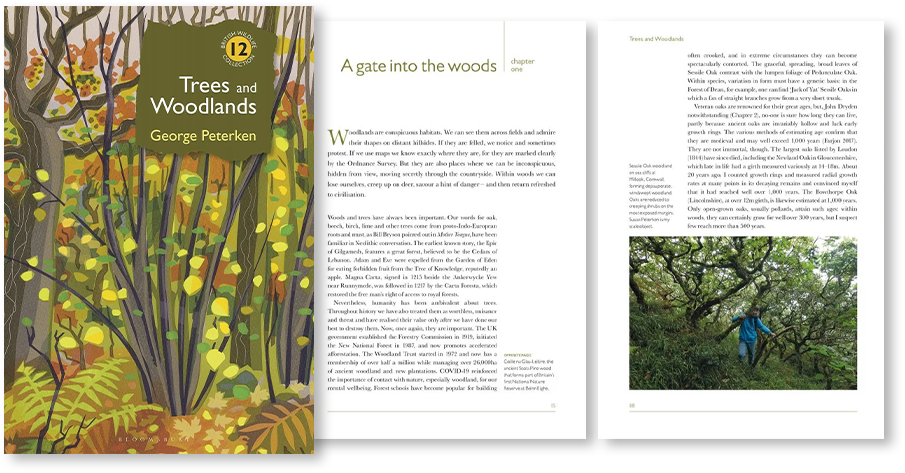

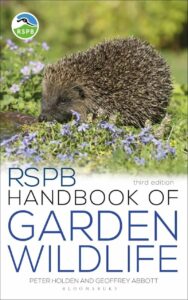

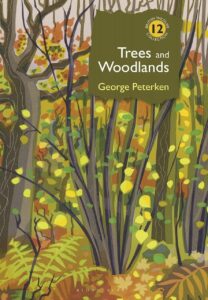

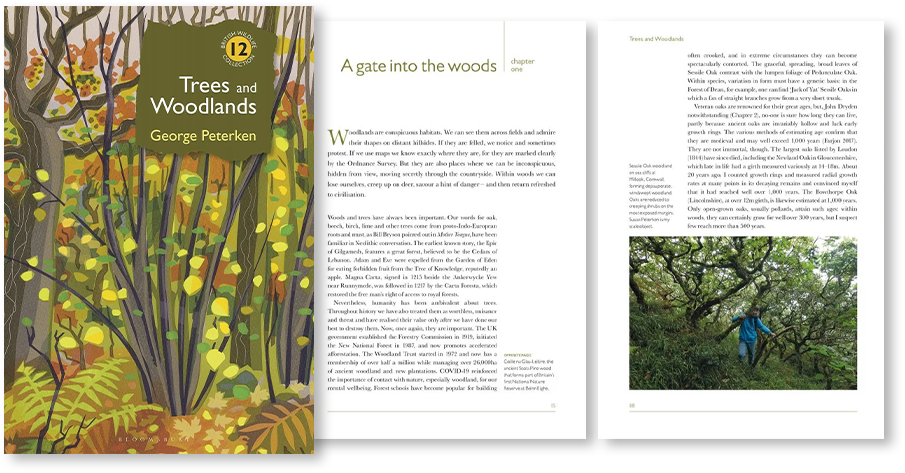

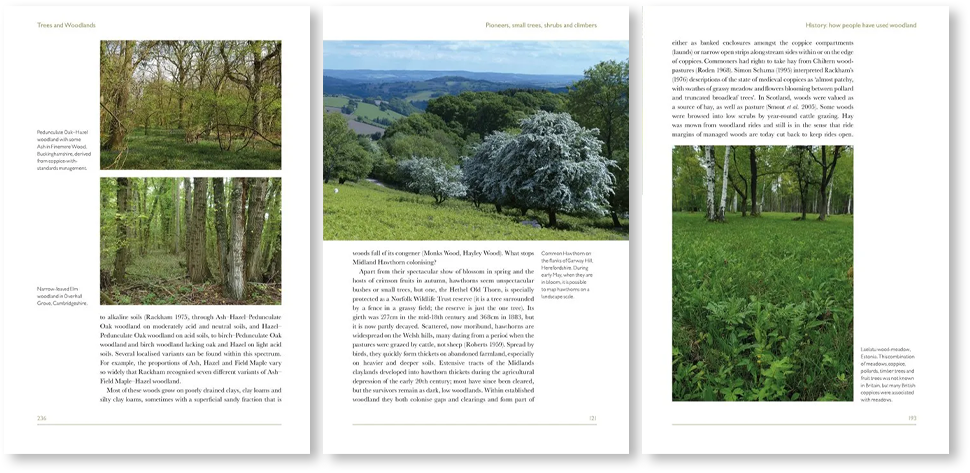

Written by one of the UK’s most highly regarded forest ecologists, Trees and Woodlands weaves together personal stories and scientific research in a thorough exploration of our woodlands, their ecology and how we as humans have interacted with them over the course of history. The 12th installment in the popular British Wildlife Collection, Trees and Woodlands will appeal to anyone who is fascinated by the stories told by our native woodlands and who is invested in their future.

Written by one of the UK’s most highly regarded forest ecologists, Trees and Woodlands weaves together personal stories and scientific research in a thorough exploration of our woodlands, their ecology and how we as humans have interacted with them over the course of history. The 12th installment in the popular British Wildlife Collection, Trees and Woodlands will appeal to anyone who is fascinated by the stories told by our native woodlands and who is invested in their future.

George Peterken worked with the Nature Conservancy to start the ancient woodland inventory and later worked as nature conservation adviser at the Forestry Commission. His research interests, which have centred on nature conservation, natural woodland and long-term and large-scale aspects of woodland ecology, benefited from a Bullard Fellowship at Harvard University. He is the author of a large number of books on both woodlands and meadows and was awarded an OBE for services to forestry in 1994.

In this Q&A we chatted with George about the book, about his life and career as a woodland ecologist and about his hopes for the future of woodlands in the UK.

Firstly, can you tell us a bit about yourself? How did you get into working with and researching woodlands?

All my childhood holidays were visits to my Mother’s family on the edge of the New Forest and the woods at Ruislip and the Chilterns were my targets as a teenage cyclist, but woods became fully imprinted with 6th form natural history camps at Beaulieu Road in the New Forest, led by my charismatic teacher, Barry Goater. I gained an entry to woodlands research when Palmer Newbould at University College, London, accepted me as a PhD student to study New Forest woodlands on a Nature Conservancy grant. Then I had the luck to be offered my ideal job as a woodland ecologist at the Nature Conservancy’s Monks Wood Experimental Station. This was a madly exciting and committed place to work where, as you will see from the book’s dedication, we thrived on the freedom we were allowed. Thereafter it was necessary to ride out the constant reorganisations thrust upon us by our paymasters, the Government.

Trees & Woodlands is a wonderfully wide-ranging book. I particularly enjoyed the frequent stories and anecdotes from your own life and career, as well as the well-researched snippets of history, culture and language. Does the human-landscape interaction interest you?

Certainly. Its much more entertaining to explain what I find in a wood in terms of human actions and unforeseen consequences than in terms of soils, climate or some other natural factor. It was Colin Tubbs who taught me this when I was a research student and he was the Nature Conservancy’s warden-naturalist for the New Forest. We would notice some feature of the vegetation distribution or woodland structure and find, more often than not, that we could understand it best as, say, an abandoned extension of agriculture or an unexpected consequence of an Act of Parliament regarding deer. Then at Monks Wood, I found that Max Hooper and John Sheail in particular were just as keen as myself to study ecology in a county record office as we were in the fields and woods. Then, of course, we all came across Oliver Rackham who had seized on the same links between history and habitats. He more than anyone has demonstrated that it’s the human element that generates most interest in the natural world. This interest also had direct benefits for my main work in woodland nature conservation: it was much easier to negotiate management that benefited nature with a woodland owner who had a keen interest in the history of his/her wood.

Your book in large part looks at the interaction between humans and woodlands over the course of history, both ancient and recent, and you state that we would have to go a long way back in time to find a woodland which was not modified by the presence of man. Where in the UK would you say is closest to a ‘natural’ or ‘unmodified’ woodland, ie one that has been affected the least by humans?

This is the subject of one of the chapters. Spending my career working with semi-natural woodlands, I spent a lot of time wondering what natural woodland looked like, then, as you can read in my contribution to Arboreal (Little Toller, 2016), came to the conclusion that natural woodland takes many different forms, but that no woodland existing since the last Ice Age could be entirely unaffected by people. We can witness approximations by allowing an ancient, semi-natural woodland to grow without direct management intervention – which is what we have studied at Lady Park Wood – or by ‘shutting the field gate’ and watching what happens as shrubs and trees invade. Whether the results look like pre-Neolithic woodland, which harboured large herbivores, is a subject that has animated woodland ecologists in recent years: some would say that the New Forest is natural in that sense, even though it has been used and managed for centuries. ‘Natural woodland’ to the general public means ‘woodland of native trees not obviously managed’ and I think ecologists should get close to that.

Extreme weather events such as storms and flooding are likely to occur at an increased frequency due to the effects of climate change. Coupled with the anthropogenic impacts of deforestation, land use change and overgrazing, this might seem to paint a dim picture for the woodlands of the future. Moving forwards, what do you think are going to be the main challenges in the UK when it comes to preserving and improving our native woodlands?

The immediate threats come from novel diseases and pests, uncontrolled deer populations and our limited ability to sustain low intensity management, which leads to neglected woods becoming less stable and losing some elements of their biodiversity. Pervasive eutrophication via rain seems to reinforce the biodiversity losses from unmanaged woods.

Deforestation is not really a problem here; storms would have less impact if woods were managed and thus stand ages were younger; trees and woods are part of the solution to flooding; and the main immediate danger from climate change may be a form of self-fulfilling prophesy when, say, beech stands are felled and replaced by introduced species that we think will better withstand future climates. Ancient woods seem reasonably well protected by public opinion, the Woodland Trust and official organisations, but we could easily drop our guard if we again believe – as we did around 1970 – that all these new woodlands will form an adequate replacement.

In terms of woodland management and the policies which govern this, what changes would you like to see in the UK over the coming years?

I’m now way out of the loop of forestry politics, but I can answer in more general terms. Throughout my career foresters have been itching to bring the now neglected former coppices back into management. Most of these are ancient woods and therefore important for nature conservation, so I took the view through the 1970s that they should be left alone, or coppiced, since their likely fate under forest management would have been planted conifers. But from 1982, when what became the Broadleaves Policy was under discussion, I advocated management based on site-native tree species, and I have not changed since. We must find or generate markets for native tree timber and wood, like Coed Cymru did and does, that would benefit wildlife and give more people a stake in the future of ancient woodlands. I like the idea of more community involvement, but in practice this usually comes down to one or two individuals. I am all in favour of leaving a representative selection of woods to grow naturally – limited intervention, or none – partly because they will act as a constant reminder of the benefits of management.

Since you began working in and researching woodlands, have there been any major technological advances that have had a signification impact on the type and quality of research that you do?

Linking my name with technological advances will elicit hollow laughter in some quarters. For years, my fieldwork has involved pencil, paper, girthing tape and metal plot markers. I have tried GPS to mark plots, but in the woods I’ve studied the errors are too large to find small plots. I do use a spreadsheet to analyse the records, though. My research started when statistical analyses were undertaken long-hand on an electric machine that whirred and juddered for ever while it did long divisions, so the arrival of computers, the internet and digital cameras is obviously the key technical advance. This has enabled astonishingly intricate analyses of huge volumes of fieldwork data, but it has also led to papers in, say, the Journal of Ecology becoming unreadable. The need now is to present and explain research results and their implications to as wide an audience as one can summon in a form that can be appreciated by a general readership. Technical advances are important and often amazing, though nothing like as important as developing the skills to write clear, accurate, non-technical, substantial and readable text. I like to think that British Wildlife magazine and the derivative Collection of books have shown the way.

Finally, what’s next for you? Do you have plans for further books?

I’m reaching the age when plans are futile, but I still like to have an on-going project. On books, I am helping Stefan Buczacki write about Churchyard Natural History. One of the most rewarding of recent projects was my collaboration with a group of professional artists, The Arborealists, in Lady Park Wood (Art meets Ecology, Sansom, 2020) and we have plans for a sequel in Staverton Park, a Suffolk wood-pasture I knew well in the late 1960s. For several years I gave up woodlands and took a close interest in meadows, which led to an earlier book in the British Wildlife Collection and gave me an enthusiasm for wood-meadows, so I’m doing what I can from a distance to help the Woodmeadow Trust.

Trees and Woodlands by George Peterken was published in February 2023. It is published by Bloomsbury Publishing and available from nhbs.com.

Wooden bat boxes

Wooden bat boxes  Woodstone and woodcrete bat boxes

Woodstone and woodcrete bat boxes Eco-plastic bat boxes

Eco-plastic bat boxes

There are also pole-mounted bat boxes (sometimes known as rocket boxes). These bat boxes are helpful alternatives in areas where there is nowhere to mount the bat box. An additional benefit is that they ensure that the bat box gains maximum sunlight in shaded areas.

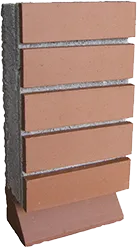

There are also pole-mounted bat boxes (sometimes known as rocket boxes). These bat boxes are helpful alternatives in areas where there is nowhere to mount the bat box. An additional benefit is that they ensure that the bat box gains maximum sunlight in shaded areas. Lastly, there are bat roost access titles and bricks. These are designed to provide bats with access points within roof or ridge tiles. Some bats will roost in the confined spaces beneath the tiles and others will use the open roof space to roost.

Lastly, there are bat roost access titles and bricks. These are designed to provide bats with access points within roof or ridge tiles. Some bats will roost in the confined spaces beneath the tiles and others will use the open roof space to roost.