The Scottish Wildlife Trust is the leading charity seeking to protect and restore the diversity of the Scottish landscape and its species. Based in Edinburgh, this membership-based organisation has a key role in the conservation of over 90,000 species through practical work, campaigning, education and management in over 100 wildlife reserves.

The Scottish Wildlife Trust is the leading charity seeking to protect and restore the diversity of the Scottish landscape and its species. Based in Edinburgh, this membership-based organisation has a key role in the conservation of over 90,000 species through practical work, campaigning, education and management in over 100 wildlife reserves.

The Scottish Wildlife Trust will be celebrating their 60th anniversary this year, marking the occasion with their storytelling campaign Words of the Wild. We recently spoke to Pete Haskell, Head of Communications and Engagement, on the work of the Scottish Wildlife Trust, its iconic projects and their goals moving forward.

Could you give us a brief introduction to the Scottish Wildlife Trust and how it was formed?

Today, the Scottish Wildlife Trust is Scotland’s leading nature conservation charity, but it all began as a small group of passionate people in Edinburgh 60 years ago.

It was in 1964 that Sir Charles Connell, along with a handful of others, decided to establish an organisation whose focus was the protection of Scotland’s wildlife for the benefit of present and future generations. Despite being run on a shoestring budget, within a year the Trust had 400 members and a long list of volunteer members of Council that included several professors, a general, several prominent landowners, a museum curator, the presenter Tom Weir and representatives from the Forestry Commission and The Nature Conservancy.

By the end of 1966, the Trust had acquired its first three wildlife reserves, and its work has continued to grow in breadth and scale ever since.

Could you tell us about the aims of the Trust, and what kind of work you undertake?

The Trust’s vision is of a network of healthy, resilient ecosystems on land and sea, supporting Scotland’s wildlife and people – something we’ve been pursuing for our 60-year history with support from our members, partners and volunteers.

The Trust successfully champions the cause of wildlife through policy and campaigning work, demonstrates best practice through practical conservation and innovative partnerships, and inspires people and communities to take positive action through education and engagement activities. We also manage a network of over 100 wildlife reserves across Scotland, welcome visitors to our three visitor centres at Montrose Basin, Loch of the Lowes and Falls of Clyde, and are a member of the UK-wide Wildlife Trusts movement.

What have been the most iconic projects for the Trust over the years? And could you tell us about your biggest challenges and successes?

Where to start! As an organisation that covers all of Scotland and all of its wildlife, we’ve been involved in a huge variety of projects over the last six decades.

In the 1980s, we had a big focus on acid rain, organising an international conference that brought together a wide range of experts to discuss the major points of evidence around the issue and the damage it causes. This resulted in delegates agreeing a detailed resolution that called for the UK Government to take decisive and immediate action to combat acid rain.

In the 1990s, one of our major focuses was peatland restoration. As well as leading a peatland campaign that raised awareness of the importance of the habitat and its wildlife, we worked in partnership with Scottish Natural Heritage (now NatureScot) to undertake one of the most comprehensive assessments of any habitat in Britain and published a peatland management handbook used by land managers across Europe.

In the 2000s, we started two of our most iconic species-focused projects. In 2008, we partnered with the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland to lead the five-year Scottish Beaver Trial in Knapdale, a groundbreaking project that saw the first formal reintroduction of a mammal anywhere in the UK. And in 2009, we established Saving Scotland’s Red Squirrels, a partnership project that continues to this day to protect our native Red Squirrel population.

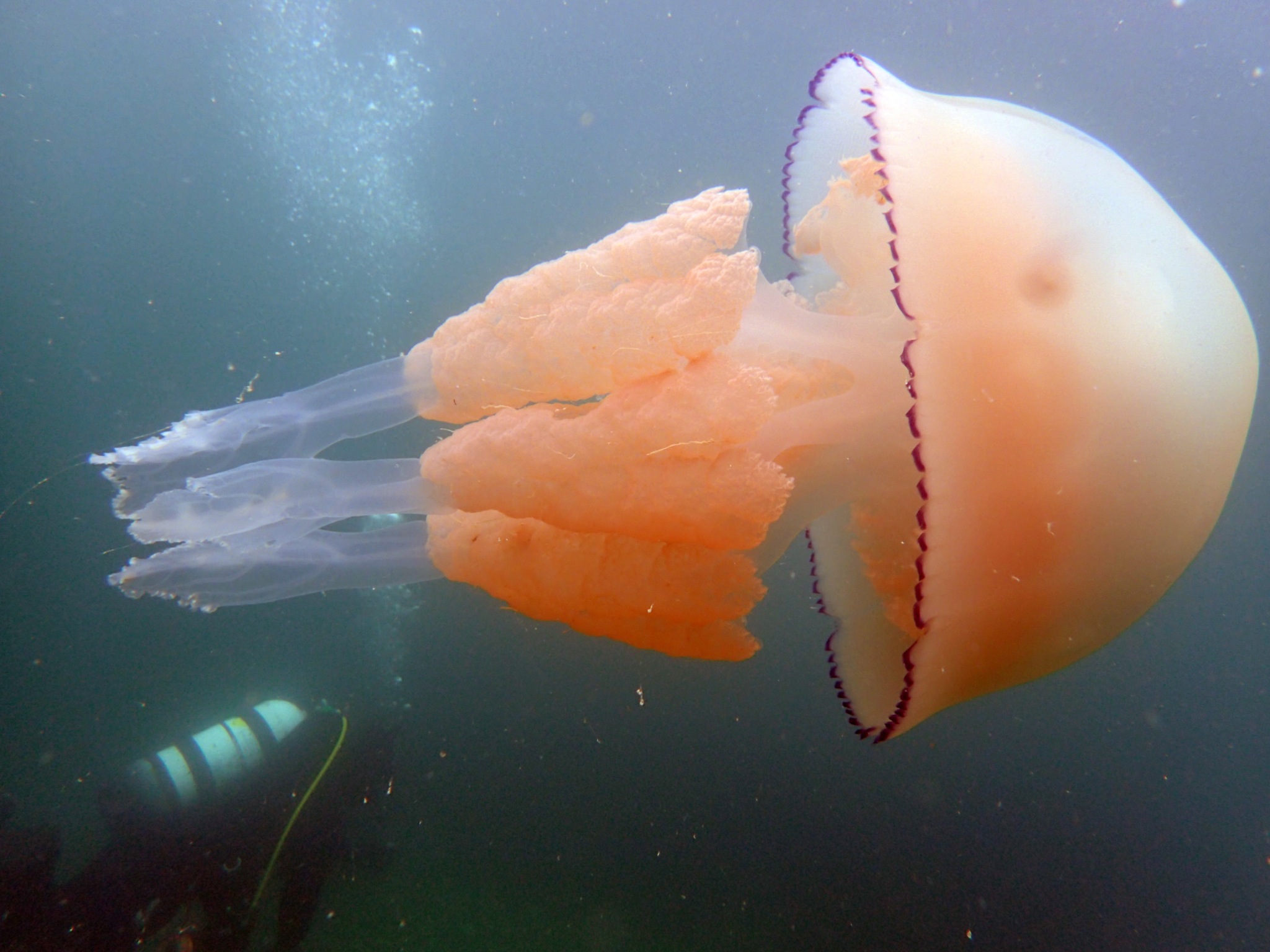

The past decade or so has seen some of our most ambitious projects to date. Our Living Landscape initiatives in Coigach and Assynt, Cumbernauld and Edinburgh are working to deliver environmental, social and economic improvements on a landscape scale. Through our Living Seas project, we have created a network of snorkel trails across Scotland to encourage more people to experience the incredible marine life that Scotland’s seas are home to. And most recently we have been progressing our Riverwoods initiative which is set to accelerate the creation of woodland habitat along Scotland’s extensive river network.

What are your hopes for the future? How do you think the Trust’s goals will change past Strategy 2030?

Our firm hope is that we begin to see nature recovery on a national scale. We have 60 years of impactful conservation behind us, but nature is in a state of crisis, with one in nine Scottish species threatened with extinction. As our life support system, nature is vital to every one of us and it will take everyone – from decision makers to community groups – to help turn the tide on nature loss.

But even if we can get over that biggest of hurdles – where nature is no longer declining and starts on an upward trajectory – there is a huge amount to do. With the UK one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world, the road to achieving our vision is a long one. There will inevitably be new challenges to overcome but the thing that unites the Trust – our staff, volunteers, members, donors and partners – is an unenduring passion and love for nature. They say you can have too much of a good thing, but when it comes to nature, that’s just not the case!

Sixty years of educating, campaigning and protecting nature is an incredible milestone. How will the Trust be celebrating this important anniversary?

Whilst there are many things going on across the Trust to celebrate our 60th anniversary, the major focus is our storytelling campaign, Words of the Wild. The campaign has three strands: a series of events focusing on the stories of some of our reserves; a new and very recently launched podcast series that will explore the stories of the Trust’s past, present and future; and a nature writing competition that encourages others to share their stories of Scotland’s wildlife and wild places in no more than 1,000 words. The competition has an adult and a junior category and is open until 31st August. There are some fantastic prizes for the winners, including some generously donated by NHBS, for which we are very grateful.

If readers would like to find out more about the Trust or enter the Words of the Wild competition, visit scottishwildlifetrust.org.uk/