Invasive non-native species cost the UK approximately £122 million per year and are a huge driver of biodiversity decline worldwide. There are a surprising number of non-native reptile and amphibian species in the UK, from non-breeding released pet terrapins to established populations of midwife toads, although the impact of some of these species on our native wildlife is not yet fully understood.

The first part of the 2022 Herpetofauna Workers Meeting included a number of talks that discussed the latest research on introduced reptile and amphibian species in the UK, including the Aesculapian Snake in Wales and the Alpine Newt in Northern Ireland. We were pleased to be able to attend and take part in this event again this year, and below is summary of some of the fascinating talks from what was an interesting and informative afternoon.

The Aesculapian Snake

The Aesculapian Snake Zamenis longissimus is a non-venomous species found across southern and central Europe, with relic populations in northern Europe. Although not native to the UK, there are two known introduced populations, one on the grounds of the Welsh Mountain Zoo in Colwyn Bay, Wales, and another along Regents Canal in London. There is also a possible third population in Bridgend in South Wales, but this is unconfirmed as of yet. Tom Major from the University of Bangor is using radio telemetry to study the population at Colwyn Bay to understand how this species is surviving, and he has gained some incredible insights into the ecology of the Aesculapian Snake over the past year.

While tracking nine adult individuals he found that on average the snakes travel the distance of approximately three and a half rugby pitches, and tend to visit one particular place where they stay for roughly four days before setting off again. This seemed to be anywhere that was warm and dry, from a chapel roof to a compost heap. By the end of the tracking period four individuals were still alive. Buzzards, stoats and cars were the reasons behind a few of the deaths, but one interesting cause was cannibalism – one tracked snake was recorded being eaten by another tracked individual, the first known occurrence of this behaviour in this species.

Turtle Tally

Reptiles and amphibians are becoming increasingly popular pets, but a lack of knowledge of their complicated care requirements or an unexpected change in an owner’s circumstances, amongst other reasons, can lead to the intentional release of these exotic animals into the wild. In order to gain an understanding of the distribution and impact of released pet terrapins in the UK in particular, Turtle Tally UK is a nationwide citizen science project that calls for the general public to submit their own terrapin sightings and photos. During her talk, Turtle Tally project lead Suzie Simpson shared some of the findings since the project began in 2019. Each year since has seen an increase in the number of sightings submitted, and hotspots have become apparent in London, Cardiff, Swansea and Liverpool. Yellow-bellied and Red-eared Slider were amongst the most frequently recorded species, and generally only one individual was recorded per sighting.

When they are out of water, terrapins are usually spotted on logs, rocks and even litter – any raised platform in a water body that they can use for basking. This also includes the nests of waterbirds, but so far there has been no evidence that these terrapins show signs of aggression to waterbirds, or that they predate on chicks. Some species, such as snappers and soft shells, would be more of a concern, however, and the Turtle Tally UK project aims to continue to collect data to further our understanding about the impacts of released pet terrapins on native wildlife. Egg laying has been observed on occasion, but due to the UK’s cooler climate, reproduction is very rarely successful. However climate change could result in more suitable conditions for breeding in the future.

The Alpine Newt in Northern Ireland

The Smooth Newt is Ireland’s only native species of newt and, with its distinctive orange belly and spotted pattern, it is easily recognisable. In September 2020, a strange looking newt was found in Northern Ireland during a bat survey. With a similarly orange belly, but without the spotted markings on its underside and darker in colour, this particular individual did not match the description of a Smooth Newt. It was soon confirmed that this was an Alpine Newt, a species found in Europe but not native to the UK. The discovery of this species is a particular concern as the Alpine Newt is a known vector of chytrid fungus. Rob Gondola, Ryan Boyle and Éinne Ó Cathasaigh provided an update of the consequent Alpine Newt surveys that took place during the following summer in 2021. Thankfully, all the swabs that were taken to test for diseases have come back negative, and they were able to determine the presence of two established populations. Further surveys and testing are hoped to continue in 2022.

Our thoughts

There were a number of other talks throughout the conference, from the ongoing study of midwife toads in the UK (another non-native species that was introduced over 100 years ago) to the impact of climate change on UK herpetofauna. This was an enlightening and fascinating afternoon and we look forward to Part 2 of the 2022 Herpetofauna Workers Meeting later on in the year. The date and location of the event will be confirmed at a future date, but any details will be made available on the ARC or ARG UK website. A recording of Part 1 will also be made available – keep an eye on the ARC website for further details.

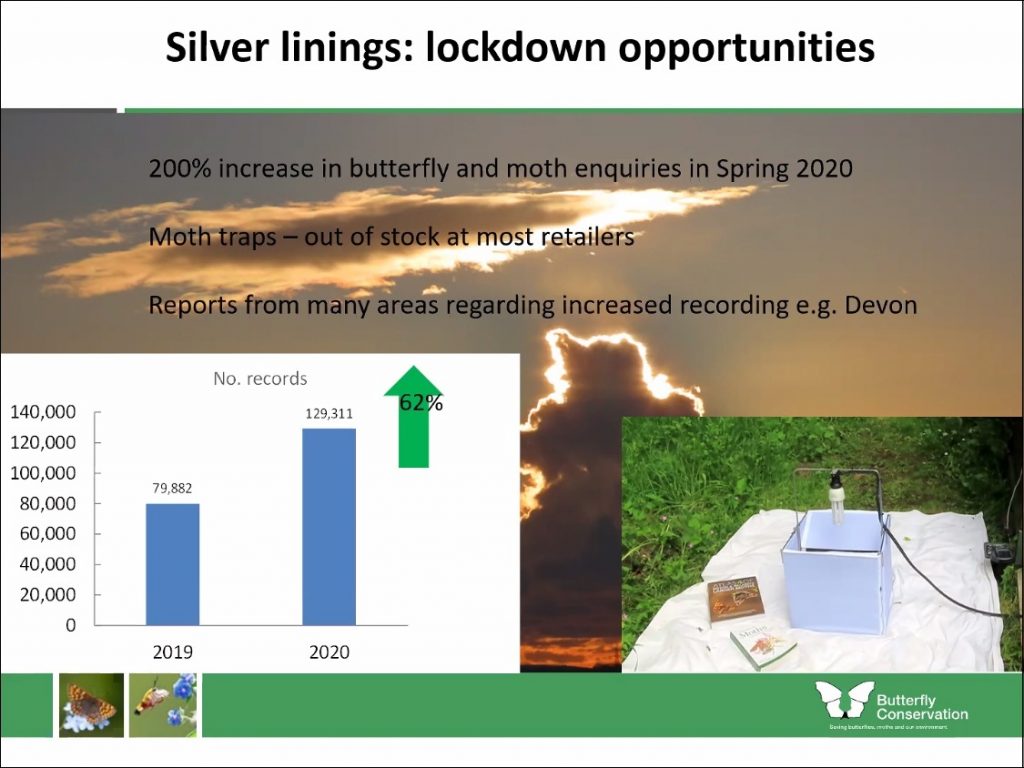

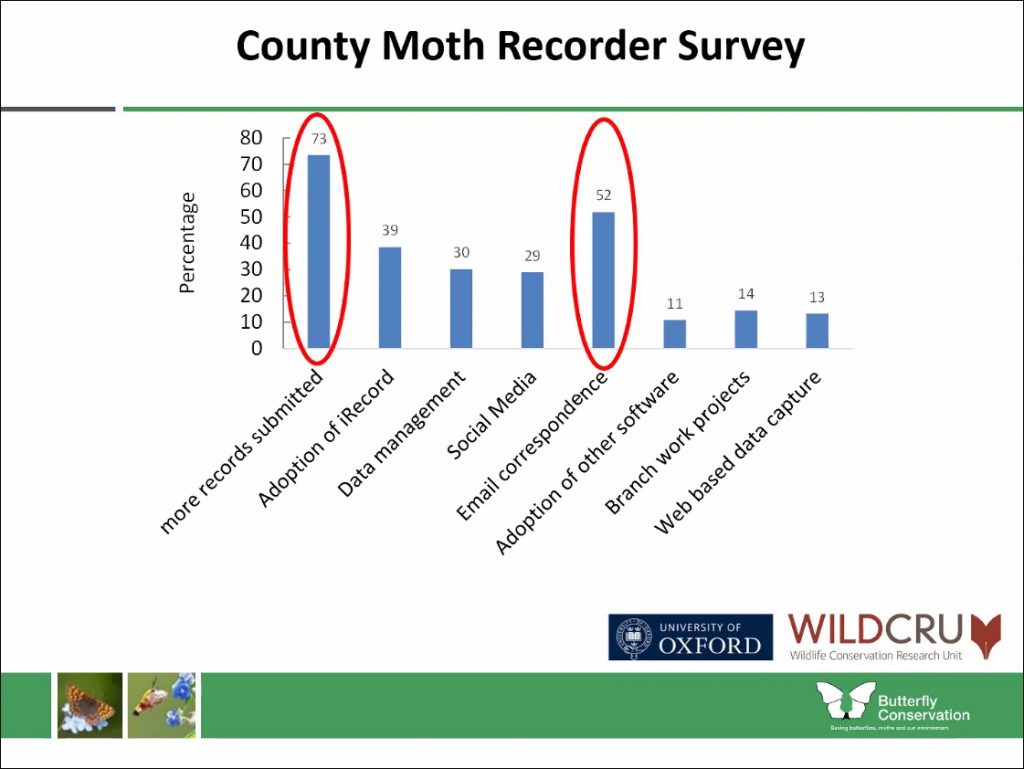

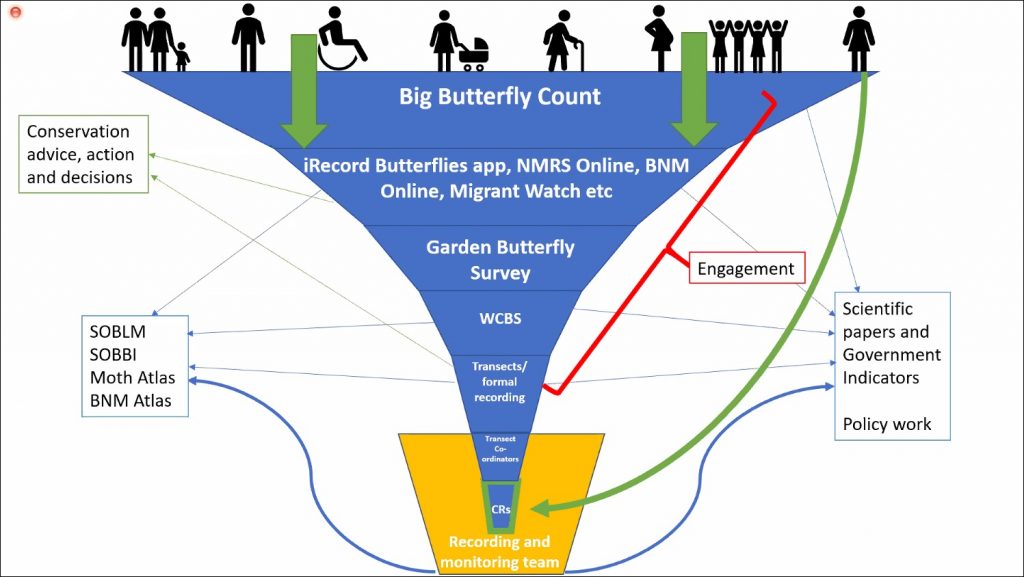

Katie spoke about the benefits of this widening pool of public participation suggesting that, not only does it expand our understanding of national biodiversity, but it also connects us meaningfully with wildlife and has positive effects on our own personal wellbeing. Public perception of moths and butterflies is improving through events like Butterfly Conservation’s Big Butterfly Count, which encourages people to log the species they see in their local patch for a set period of time using a dedicated app. The wealth of sightings that come through apps like this and iRecord – alongside information gathered from social media and anecdotal sources – has meant that the recording process is a vast and time consuming activity for volunteers. Katie spoke on how this process currently works and speculated on how it might be streamlined moving forwards.

Katie spoke about the benefits of this widening pool of public participation suggesting that, not only does it expand our understanding of national biodiversity, but it also connects us meaningfully with wildlife and has positive effects on our own personal wellbeing. Public perception of moths and butterflies is improving through events like Butterfly Conservation’s Big Butterfly Count, which encourages people to log the species they see in their local patch for a set period of time using a dedicated app. The wealth of sightings that come through apps like this and iRecord – alongside information gathered from social media and anecdotal sources – has meant that the recording process is a vast and time consuming activity for volunteers. Katie spoke on how this process currently works and speculated on how it might be streamlined moving forwards.

The compilation of data for the new

The compilation of data for the new

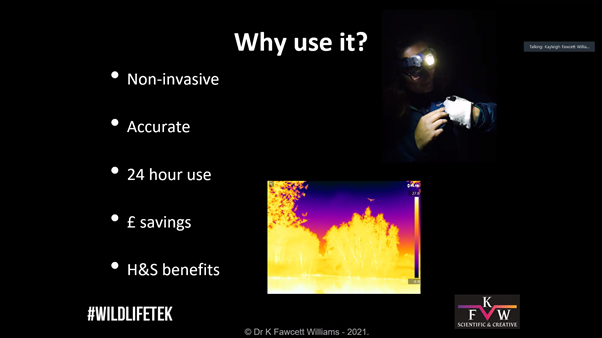

We joined the session on thermal imaging run by Dr Kayleigh Fawcett Williams to learn more about how this equipment is being used in ecological consultancy. Most participants were new to thermal imagery, so Dr Fawcett Williams walked us through the basics. She explained that thermal imaging works by picking up thermoelectrics from the environment – infrared radiation, meaning that it is not at all invasive to the animals as the scopes emit no light (as opposed to night vision cameras that use infrared to light up the subjects).

We joined the session on thermal imaging run by Dr Kayleigh Fawcett Williams to learn more about how this equipment is being used in ecological consultancy. Most participants were new to thermal imagery, so Dr Fawcett Williams walked us through the basics. She explained that thermal imaging works by picking up thermoelectrics from the environment – infrared radiation, meaning that it is not at all invasive to the animals as the scopes emit no light (as opposed to night vision cameras that use infrared to light up the subjects). The benefits of this survey method were explained, including: ability to use at all times of day and for long durations and cost effectiveness due to lack of man power needed. Thermal imaging can reduce the risk of false positives when it comes to identification of species and also provide a wider picture of landscape or infrastructure use by illustrating patterns of activity. She also highlighted that it is good for multidisciplinary work (e.g. for firms that work with engineers) as it has a range of applications that are not just ecology based.

The benefits of this survey method were explained, including: ability to use at all times of day and for long durations and cost effectiveness due to lack of man power needed. Thermal imaging can reduce the risk of false positives when it comes to identification of species and also provide a wider picture of landscape or infrastructure use by illustrating patterns of activity. She also highlighted that it is good for multidisciplinary work (e.g. for firms that work with engineers) as it has a range of applications that are not just ecology based. She explained that bats are protected by law and that while only licensed individuals should be in contact with bats, first aid is considered emergency care and so this can be administered without a license. That being said, you will need to be able to justify any contact you have had with a bat so she strongly suggested that you keep records of the encounter.

She explained that bats are protected by law and that while only licensed individuals should be in contact with bats, first aid is considered emergency care and so this can be administered without a license. That being said, you will need to be able to justify any contact you have had with a bat so she strongly suggested that you keep records of the encounter.

CIEEM’s

CIEEM’s

• Improve access – Gardens are only useful for hedgehogs if they can access them. Plus, hedgehogs move long distances throughout the night to find enough food, so creating networks of gardens that they can move between is important. By cutting a 13cm diameter hole in the bottom of a fence or removing a brick from the base of a wall, you can help to provide access and link your garden with surrounding ones.

• Improve access – Gardens are only useful for hedgehogs if they can access them. Plus, hedgehogs move long distances throughout the night to find enough food, so creating networks of gardens that they can move between is important. By cutting a 13cm diameter hole in the bottom of a fence or removing a brick from the base of a wall, you can help to provide access and link your garden with surrounding ones.