***** A wonderful graphical introduction to the inner workings of an ant colony

***** A wonderful graphical introduction to the inner workings of an ant colony

This one grabbed my attention as soon as it was announced. Not a comic or graphic novel, but an A4-format book about ant colonies that is chock-a-block with infographics? Yes, please! Showcasing the best of what science illustration can be and combining it with a genuine outsider’s interest in entomology, The Ant Collective makes for a wonderful graphical introduction that will appeal to a very broad audience of all ages.

This book was originally published in German in 2022 as Das Ameisenkollektiv by Kosmos Verlag. It was quickly snapped up for translation into French and Spanish before Princeton University Press published it in English in 2024, courtesy of translator Alexandra Bird. Armin Schieb is a freelance science illustrator based in Hamburg, Germany, and this book is derived from his master’s thesis in Informative Illustration at the Hamburg University of Applied Sciences. His portfolio shows infographics, 3D models, and cover illustrations for a range of clients, from magazines to newspapers to publishers, but this book represents his first published work to date.

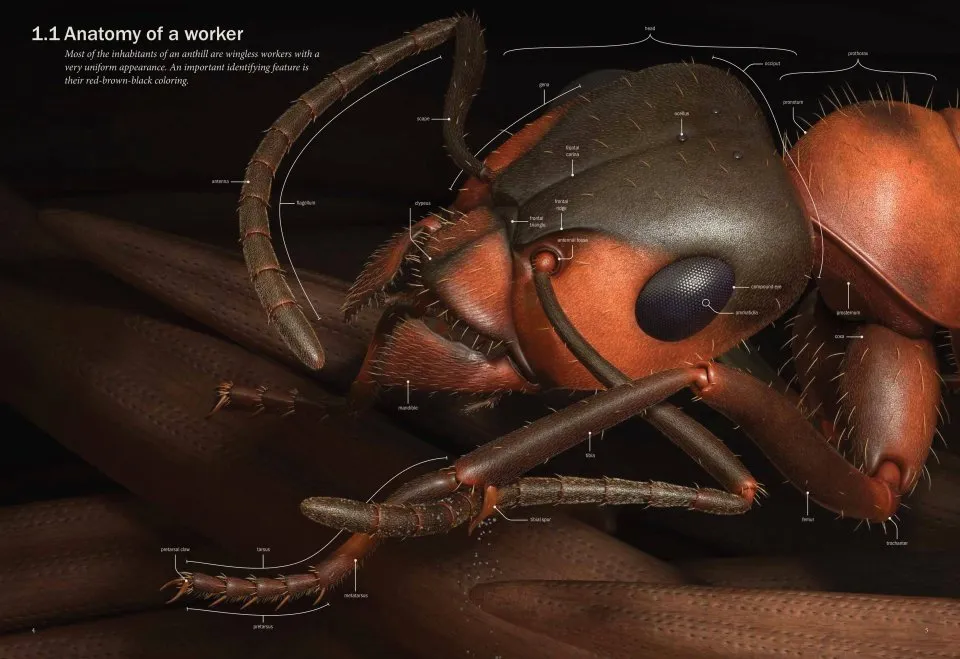

Based on direct observations, sketches, and photos of red wood ants (Formica rufa), Schieb has designed 61 highly detailed computer-generated illustrations showing ants from a bug’s eye perspective that entomologists can only dream of. The eight chapters each contain a mixture of full-page spreads with naturalistic 3D renderings of landscapes full of ants, and pages with numerous smaller infographics that explain how colonies function. Annotations are scattered throughout to provide context to what you are looking at. Neatly, many of the full-page spreads continue overleaf, forming eight-page tableaux. One can only imagine what they would have looked like if the publisher had included them as gatefolds!

Next to obligatory drawings introducing ant anatomy, the focus of this book is on colony-level behaviour, with chapters depicting nuptial flights, nest establishment and construction, seasonal cycles of nest maintenance, foraging, trail formation, food acquisition and defence, reproduction, nest defence, and the formation of new colonies. The clever use of cutaway illustrations reveals processes that normally play out unseen underground.

There are some memorable scenes in here showing e.g. green woodpeckers and boars raiding ant nests. The woodpecker illustration stands out in particular. Red wood ants defend themselves by spraying formic acid and are normally inedible. The birds, though, have turned the tables on the ants twice over, picking them up in their beak and rubbing them on their feathers where the ants discharge the contents of their poison glands. As an added bonus, the formic acid repels feather parasites. This whole story is illustrated by overlaying several semitransparent motion frames of a woodpecker twisting its head and is glorious to behold. Elsewhere, Schieb uses motion blur to good effect to highlight the action-packed nature of spiders and antlions catching hapless ants.

Needless to say, this book is full of fascinating titbits of information. Schieb explains the phenomenon of age polyethism that I first encountered in Ant Architecture. Young ants tend to stay inside or close to the nest, while older ants venture further out to do the dangerous job of foraging (though Ant Encounters for some criticism of this idea). Schieb (perhaps unwittingly) offers an excellent illustration of colony behaviour arising through interaction networks when he shows how foraging trails wax and wane as a function of behavioural interactions between ants. There is similarly a deft explanation of the anatomical details of the eyes that allow them to see both polarized and unpolarized light: straight or spiralling stacks of light-sensitive tubules. It is one of those concepts where a picture says more than a thousand words. The only criticism I have of this particular section is that I would have opened it with the otherwise excellent illustration explaining sky polarization. Additionally, I would have added an infographic that explains what polarized light actually is, as it is a surprisingly tricky phenomenon to explain. Michael Land’s book Eyes to See contains a good picture, whereas Schieb basically takes it as a given that readers will understand what he means when writing that “almost all photons in a polarized light ray vibrate in the same plane” (p. 64).

The promotional blurb for the book mentions it draws on the latest science though I was left somewhat confused when I finished it. Schieb is obviously not an entomologist but a graphic artist. There is no mention of the project having benefited from one or several entomologists acting as consultants to give the contents the once-over for scientific accuracy. There is no acknowledgements section where Schieb credits scientists for advice and input. There is not even a list of references or recommended reading included. Or is there? Since I do not have access to the German original I had to resort to some online sleuthing and found a preview on Amazon.de that includes the reference list on p. 126. This reveals that, yes, he has consulted books and scientific papers in both English and German, including that evergreen The Ants, an older edition of Insect Physiology and Biochemistry, and both specialist and general German books on forest insects. So, Schieb did his homework, Kosmos referenced it, but for some bizarre reason, Princeton simply omitted it, as the page between 125 and 127 is… blank! Did I just happen to receive a dud to review? Checking eight other copies at our warehouse confirmed that, no, this is a feature, not a bug. Hopefully, if there are future print runs, this is a detail that can be rectified, as it could easily leave readers with the wrong impression.

The promotional blurb for the book mentions it draws on the latest science though I was left somewhat confused when I finished it. Schieb is obviously not an entomologist but a graphic artist. There is no mention of the project having benefited from one or several entomologists acting as consultants to give the contents the once-over for scientific accuracy. There is no acknowledgements section where Schieb credits scientists for advice and input. There is not even a list of references or recommended reading included. Or is there? Since I do not have access to the German original I had to resort to some online sleuthing and found a preview on Amazon.de that includes the reference list on p. 126. This reveals that, yes, he has consulted books and scientific papers in both English and German, including that evergreen The Ants, an older edition of Insect Physiology and Biochemistry, and both specialist and general German books on forest insects. So, Schieb did his homework, Kosmos referenced it, but for some bizarre reason, Princeton simply omitted it, as the page between 125 and 127 is… blank! Did I just happen to receive a dud to review? Checking eight other copies at our warehouse confirmed that, no, this is a feature, not a bug. Hopefully, if there are future print runs, this is a detail that can be rectified, as it could easily leave readers with the wrong impression.

Over the years, I have reviewed some seriously impressive photographic books on ants, covering amongst others army ants, desert ants, and myrmecophiles. Despite being a slimmer volume written for a general audience, The Ant Collective rubs shoulders with the greats where visual content is concerned. This is a feast for the eyes that will lure newcomers into entomology but should also please seasoned myrmecologists.

A final thing to note is that this book tells the biology of a *single* species. Wood ants are well-studied as far as ants go, but as the subtitle indicates, this is a look inside the world of *a* ant colony. It would be a mistake to come away from this book thinking that this is how colonies of all ant species function. The world of ants is one of bewildering diversity, though themes and unifying principles are starting to emerge.

The Ant Collective is available from our online bookstore.

Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Chapter 3 bundles together research on numerous other senses, including ones familiar (smell, taste, and hearing) and unfamiliar to us (perception of polarised light, Earth’s magnetic field, and electric fields). The antennae of bees, in particular, are marvels; Chittka likens them to a biological Swiss army knife, packing numerous different sense organs into two small appendages. Tightly connected to sensory biology is how this incoming information is processed in the brain, though Chittka postpones discussing neurobiology to chapter 9. He describes the discovery and function of different brain areas and highlights the work of Frederick Kenyon who would inspire the better-remembered Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Thanks to them, we now understand that brains consist of numerous specialised nerve cells. Though the bee brain is small, Chittka argues that size is a poor predictor of cognitive skills; it is the wiring of neurons that matters. Rather than be surprised that small-brained insects such as bees can do so many clever things, Chittka instead tickles the reader with the opposite question: “Why does any animal need as large a brain as a bee’s?” (p. 153).

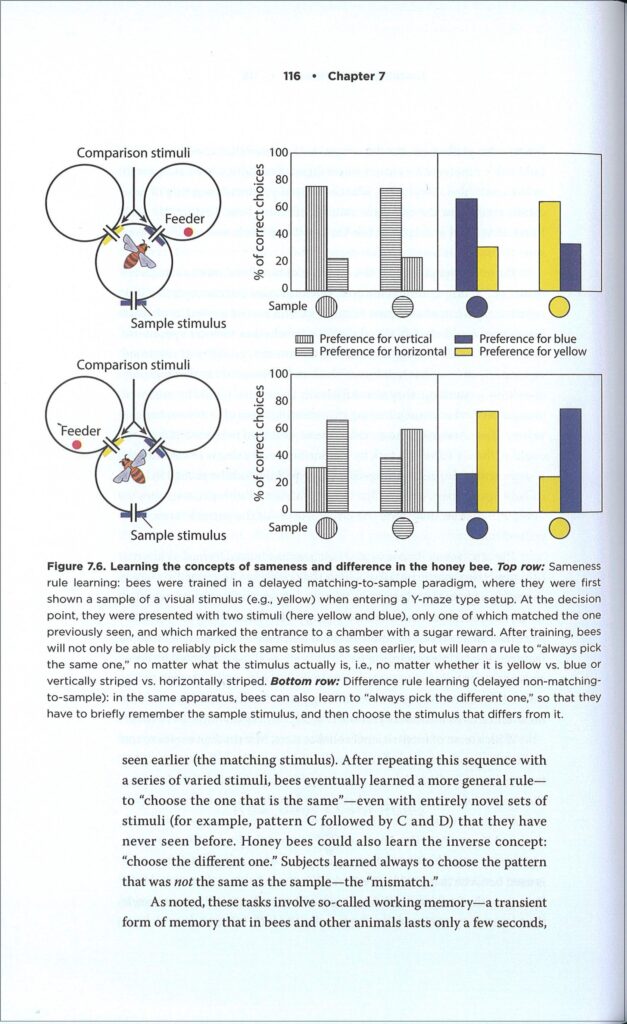

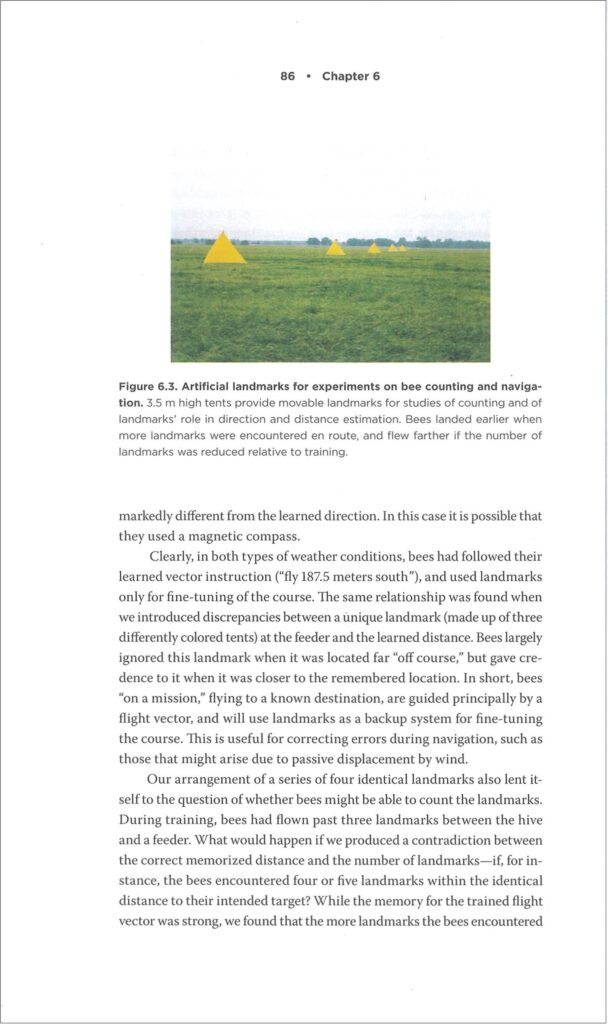

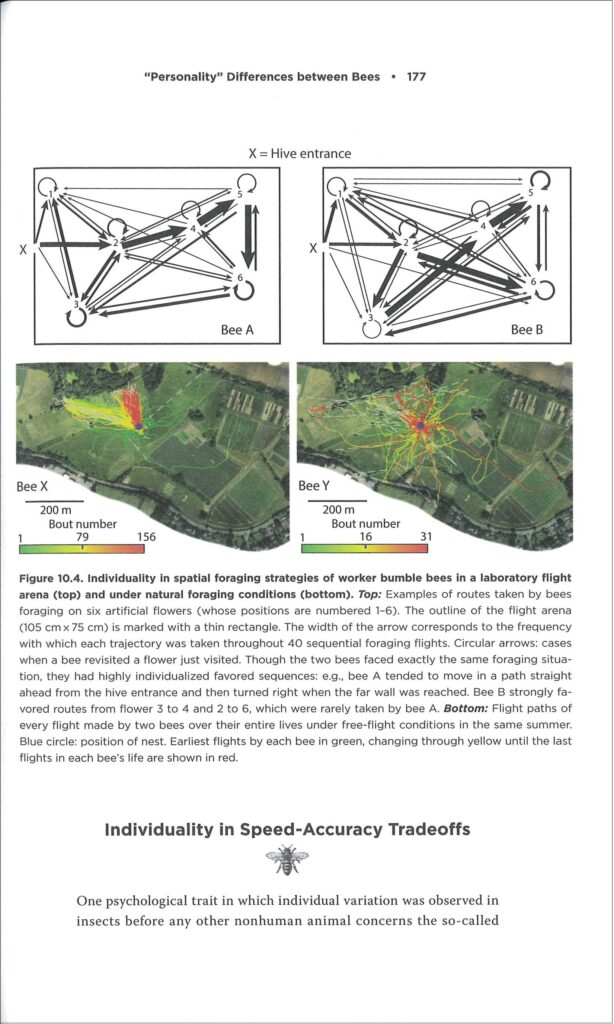

Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Chapter 3 bundles together research on numerous other senses, including ones familiar (smell, taste, and hearing) and unfamiliar to us (perception of polarised light, Earth’s magnetic field, and electric fields). The antennae of bees, in particular, are marvels; Chittka likens them to a biological Swiss army knife, packing numerous different sense organs into two small appendages. Tightly connected to sensory biology is how this incoming information is processed in the brain, though Chittka postpones discussing neurobiology to chapter 9. He describes the discovery and function of different brain areas and highlights the work of Frederick Kenyon who would inspire the better-remembered Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Thanks to them, we now understand that brains consist of numerous specialised nerve cells. Though the bee brain is small, Chittka argues that size is a poor predictor of cognitive skills; it is the wiring of neurons that matters. Rather than be surprised that small-brained insects such as bees can do so many clever things, Chittka instead tickles the reader with the opposite question: “Why does any animal need as large a brain as a bee’s?” (p. 153). What clever things do bees do, you ask? That is the subject of the preceding five chapters where Chittka surveys a large body of behavioural research. Honey bees are famous for their waggle dance by which they communicate the location of flowers but also, this was news to me, the location of potential nest sites when the swarm relocates. But Chittka discusses more, much more: how bees navigate space using landmarks, show a rudimentary form of counting, solve the travelling salesman problem, learn to extract nectar from complex flowers, learn when to exploit certain flowers (and when to ignore them), and learn new tricks by observing other bees. But what about instinct, something most behaviours were traditionally ascribed to? He has some insightful comments on this: “even the most elemental behavior routines need to be refined by learning: instinct provides little more than a rough template” (p. 50). What really made me fall off my chair is that bees have long been outsmarting researchers in choice experiments. Many behavioural experiments take the form of choice tests, where bees need to pick between two locations or objects that differ in e.g. colour or shape with one option containing a sugary solution as a reward. Bumblebees would simply be lazy and check out both options in random order. Until, that is, protocols were modified by adding a bitter-tasting solution to the wrong choice as a penalty.

What clever things do bees do, you ask? That is the subject of the preceding five chapters where Chittka surveys a large body of behavioural research. Honey bees are famous for their waggle dance by which they communicate the location of flowers but also, this was news to me, the location of potential nest sites when the swarm relocates. But Chittka discusses more, much more: how bees navigate space using landmarks, show a rudimentary form of counting, solve the travelling salesman problem, learn to extract nectar from complex flowers, learn when to exploit certain flowers (and when to ignore them), and learn new tricks by observing other bees. But what about instinct, something most behaviours were traditionally ascribed to? He has some insightful comments on this: “even the most elemental behavior routines need to be refined by learning: instinct provides little more than a rough template” (p. 50). What really made me fall off my chair is that bees have long been outsmarting researchers in choice experiments. Many behavioural experiments take the form of choice tests, where bees need to pick between two locations or objects that differ in e.g. colour or shape with one option containing a sugary solution as a reward. Bumblebees would simply be lazy and check out both options in random order. Until, that is, protocols were modified by adding a bitter-tasting solution to the wrong choice as a penalty. As mentioned above, this book is focused. If you enjoy reading about the facts and the study system with minimal (autobiographical) diversions, Chittka has got you covered. The only digression he allows himself is to include biographical details of older generations of scientists. This includes inspiring tales such as Karl von Frisch who described the honey bee waggle dance and later barely escaped being dismissed from his post by the Nazis. And look out for repeat appearances of Charles Turner, a now largely forgotten African American scientist who published pioneering work despite having been denied a professorship based on his ethnicity. But there are also tragic stories such as Kenyon’s, who snapped under pressure of not securing a permanent job and was incarcerated in a lunatic asylum where he died more than 40 years later, alone and forgotten. Chittka includes occasional quotations from historical literature to show that “many seemingly contemporary ideas about the minds of bees had already been expressed, in some form, over a century ago” (p. 15).

As mentioned above, this book is focused. If you enjoy reading about the facts and the study system with minimal (autobiographical) diversions, Chittka has got you covered. The only digression he allows himself is to include biographical details of older generations of scientists. This includes inspiring tales such as Karl von Frisch who described the honey bee waggle dance and later barely escaped being dismissed from his post by the Nazis. And look out for repeat appearances of Charles Turner, a now largely forgotten African American scientist who published pioneering work despite having been denied a professorship based on his ethnicity. But there are also tragic stories such as Kenyon’s, who snapped under pressure of not securing a permanent job and was incarcerated in a lunatic asylum where he died more than 40 years later, alone and forgotten. Chittka includes occasional quotations from historical literature to show that “many seemingly contemporary ideas about the minds of bees had already been expressed, in some form, over a century ago” (p. 15).