We recently became aware of a fantastic series of manuals that give readers instructions on how to clean, prepare, and articulate animal skeletons. We caught up with the author, Lee Post, a self-professed bone man, to ask him more about these guides and his work.

We recently became aware of a fantastic series of manuals that give readers instructions on how to clean, prepare, and articulate animal skeletons. We caught up with the author, Lee Post, a self-professed bone man, to ask him more about these guides and his work.

Hello Lee, thanks for the opportunity to ask you some questions. How does one become a bone builder? Was this always something you were interested in or did you fall into this more or less by accident?

As a child, growing up, I was a classic nature nerd. My room looked more like a Victorian curio cabinet than some place someone might actually sleep. Anything related to the animal kingdom was something I was interested in collecting. The ultimate treasures were bones and skulls. But I had never thought about articulating anything myself. My passion for articulating skeletons grew out of a move to a small town in Alaska that had a very progressive little natural history museum. I had a part-time job in the winter and volunteered the rest of my time at this museum. I was given an opportunity to research and articulate a 17 foot Stejnegers Beaked Whale the staff had collected and cleaned. That was my first winter project. My research into how to articulate that skeleton came to a lot of dead ends and some questionable advice. I could find nothing in print on building whale skeletons. With a background in bicycle mechanics and carpentry, and a lot of suggestions from local craftsmen and women, I got that skeleton together, and from then on I never stopped working with bones. Collecting, cleaning, building, illustrating, curating. It was being in the right place at the right time under the right circumstances. In other words, a total accident.

What made you decide to write manuals on constructing and articulating skeletons?

For years I’d been cleaning and articulating a skeleton or two each year. This led to a 3-year Pratt Museum, Homer High School collaborative project, in which I worked at the school with all kinds of interested students. We articulated a 41 foot long sperm whale in the school, and the

following year students worked on about a dozen other skeleton projects, ranging from sea otters to a moose, to porpoises, to a porcupine. The exhibited work they did in their school was open to the public over the following couple of summers. Teachers and educators from lots of places that saw those exhibits wanted to know how they could do similar projects with their students. I had kept a notebook on almost every skeleton I worked on and from those made some crude, hand-lettered, illustrated manuals on how to prepare and build animal skeletons. My day job was working in a bookstore, and there were no books in print on working with bones. This was 20 years ago. Later, an intersection of those hand-printed, photocopied notes, and me, and a talented lady (now my wife) who knew how to do desktop publishing, resulted in the birth of the Bone Building Books about 15 years ago.

Who buys these guides? Do you find that they are used by museum curators, or mostly by individual naturalists? And what has the feedback been?

The manuals were originally written for teachers and students who wanted to do a museum quality skeleton on a limited budget, with materials they

should be able to find even in a small town. Over the years, the manuals have been enlarged and corrected and improved each time I have worked on that type of skeleton. I’m always trying different materials and testing new techniques. Today they are used by everyone from teachers to museum workers, to home hobbyists to University projects with students. The other group of people who were getting these were bone collectors and zoo archaeologists who really just wanted to look at the pictures. They had no interest in the articles or in building a skeleton. And the manuals didn’t even have a centerfold. The feedback has been very enthusiastic. For many hobbyists and home naturalists who have wanted to get accurate information on how to prepare the bones and build the skeletons, these have been their bibles. When people get stuck, they often e-mail me. That’s often a clue I didn’t explain something well enough, and the next revision will try to remedy that.

What advice do you have for aspiring bone builders?

Don’t plan on doing this for a career. You would likely starve. But if this is your interest and passion, there is enough information out there these days that you should definitely pursue that interest. There are no skeleton police. There are no university degrees in this. Many of the best skeleton articulations of land mammals are being done by home hobbyists. You too could be doing that.

From the short video clip of Indie Alaska that I saw, it seems you teach courses to students. Do you also offer workshops for museum professionals?

Many of my favorite projects have been done with groups of interns and docents in museums and marine-life centers. On occasion, the paid staff have joined in, but usually, the staff has too much other work to be able to take the time off to do much hands-on work building a large skeleton. My favorite projects are when I have an enthusiastic group of volunteers and an organization with someone who wants to organize a large skeleton build project. Then, I get to teach and be the foreman and boss around the volunteers, who get the thrill of working with real bones and being part of a team that builds a world-class skeleton.

Are there any particularly challenging skeletons you worked on, or any particular animal skeletons you would still love to tackle?

I’m still sorting out sea turtle skeletons. They have very unusual bones. I’ll be trying to figure out a crocodile skeleton soon. I’m always interested in working on new marine mammal species. They are the animals I have the most experience with.

You have now written nine guides to specific animals and animal groups, plus a general reference book, the Bone Builder’s Notebook. Are there plans to write any more guides?

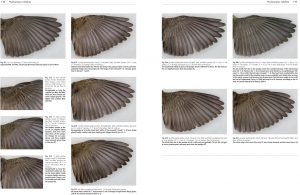

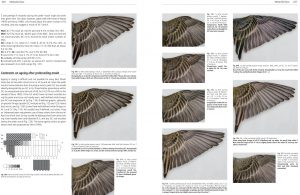

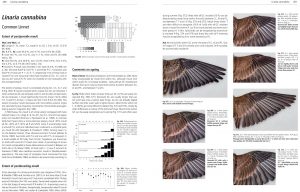

I’m doing a lot of illustration work on bird bones. I can imagine these might

one day get compiled into some type of identification guide to bird bones. I’m also getting more and more requests for information on articulating reptiles. I live in Alaska, and there is a serious lack of reptiles in my area. However, I’ll be working on some large reptiles in Mexico in the near future, and I never know when I’ll get so inspired that I might try to write something useful on how those bones fit together.

You can discover the complete selection of Bone Building Books on the NHBS website

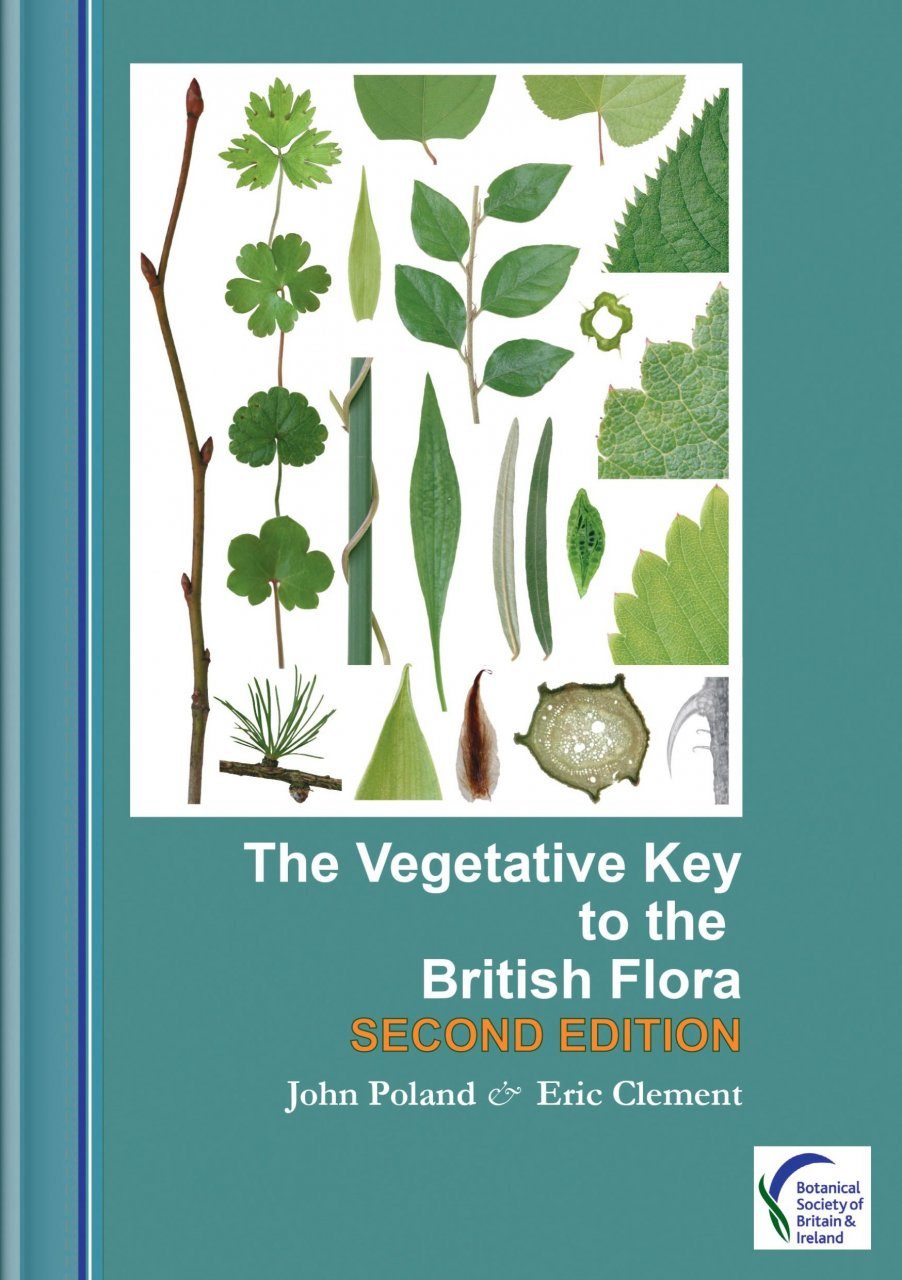

Why did you consider producing a second edition of The Vegetative Key to the British Flora and how long has it been in preparation?

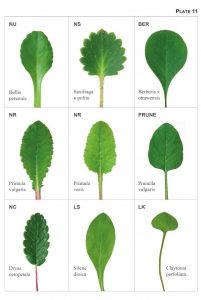

Why did you consider producing a second edition of The Vegetative Key to the British Flora and how long has it been in preparation? Is there one easy mistake that can be made when identifying plants in their vegetative state?

Is there one easy mistake that can be made when identifying plants in their vegetative state?

Recently we spoke to Helen Parr from the Devon Greater Horseshoe Bat Project about the wonderful work that is done in our local area for this rare species. Helen Parr also details the importance of conserving the Greater Horseshoe Bat, how we all can help ensure its survival and shares her hopes for the future.

Recently we spoke to Helen Parr from the Devon Greater Horseshoe Bat Project about the wonderful work that is done in our local area for this rare species. Helen Parr also details the importance of conserving the Greater Horseshoe Bat, how we all can help ensure its survival and shares her hopes for the future.