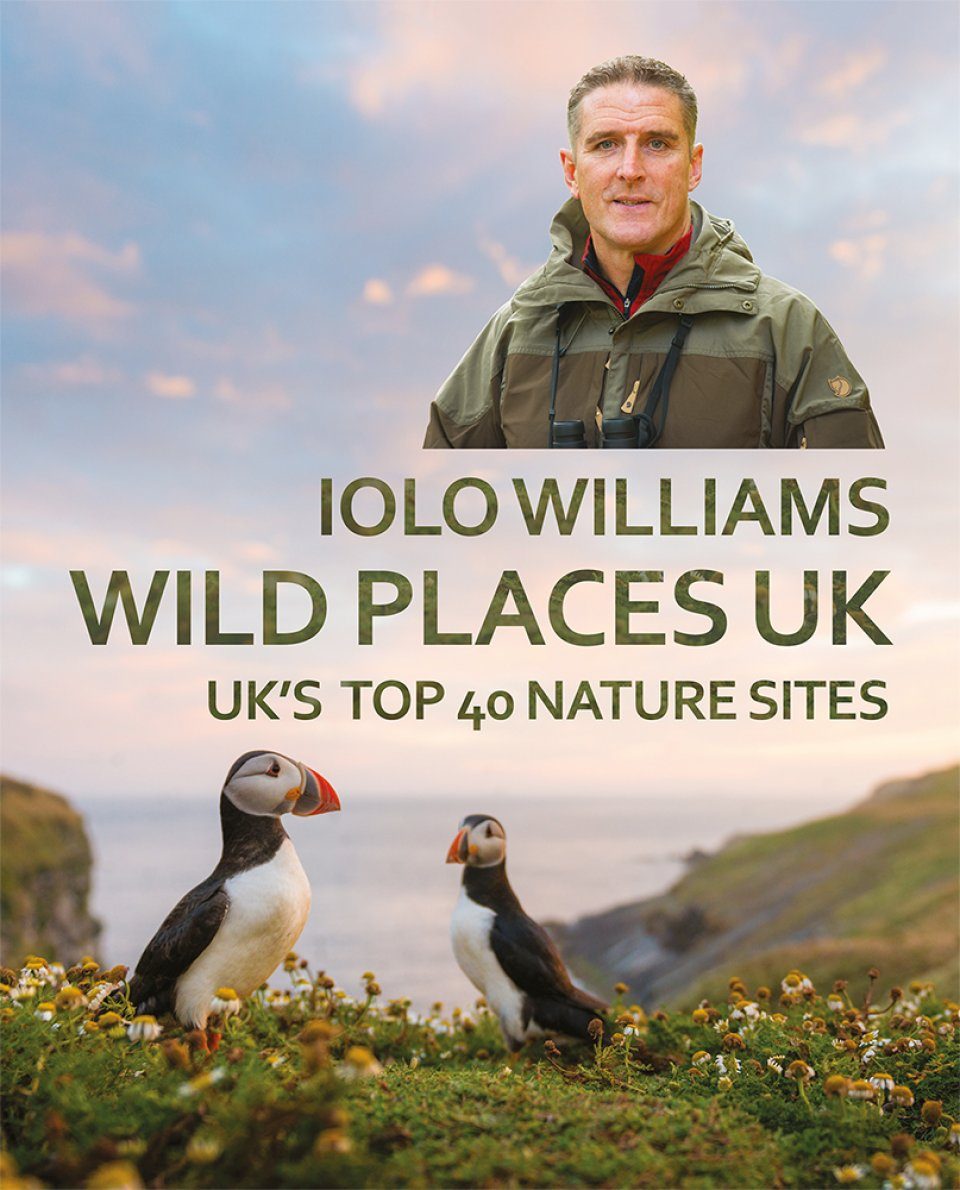

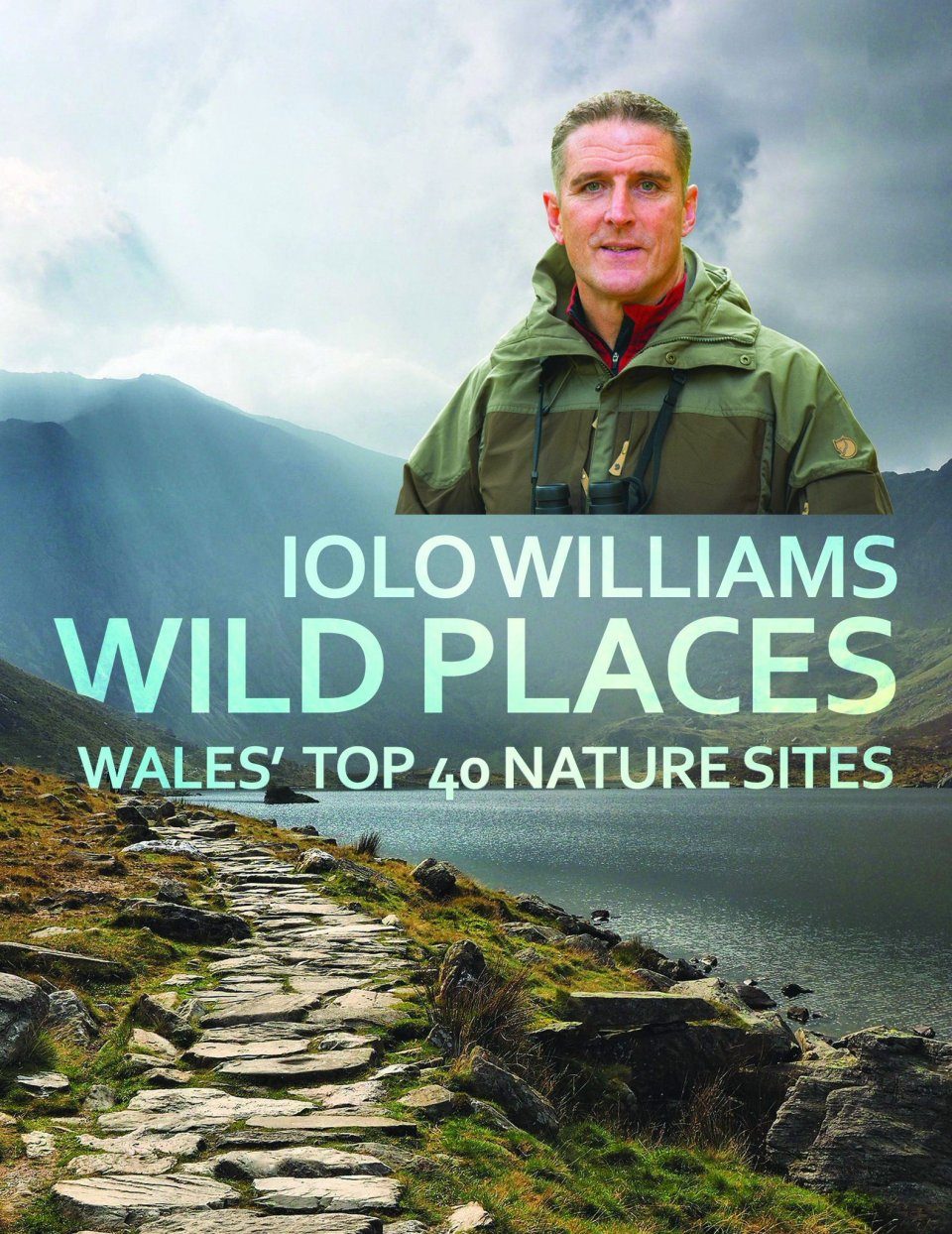

Iolo Williams was born and brought up in mid Wales. After gaining an ecology degree he worked for the RSPB for almost 15 years as Species Officer for Wales. In the late 1990s Iolo left the Society to work full-time in the media, presenting in both Welsh and English. He co-presented Springwatch 2020 and is a tireless campaigner for wildlife and conservation.

We caught up with Iolo and asked him a few questions on: lockdown, rewilding, Brexit and the future for nature.

Wales has a variety of landscapes and environments; do you have a favourite habitat?

I was born and brought up in mid-Wales and grew up in a small village called Llanwddyn (Lake Vyrnwy), which was a fantastic area with a mixture of habitats. But, where I am happiest really is up on the high ground: up on the mountains, up on the moorland, enjoying not just the solitude and the scenery, but some of the amazing wildlife, such as: black grouse, merlin and hen harrier. You have also got sundews, butterworts, and bog asphodel; all amazing and well adapted to these harsh conditions. So that’s where I’m happiest really – when I want a day by myself, away from everyone, that’s where I head for.

Do you think ecotourism and nature capital have a role to play in wildlife conservation?

I think ecotourism is absolutely vital for the future survival of our wildlife and our habitats, and ourselves too. It’s only when we educate people, it’s only when people see what’s out there, it’s only then that people grow to appreciate it and will then fight to ensure that it survives for their children and for future generations. So, I do believe it’s a vital part of conservation and education.

But of course ecotourism does involve travel, which is a dilemma. I travel a lot less than I used to and off-set it as much as I can, but I learned a lesson whilst visiting Chitwan National Park in Nepal and lamenting my carbon footprint involved to get there. The head ranger heard me and said, ‘Listen, if you didn’t come here, there wouldn’t be a national park. The government wants the wood, wants to log these trees you see here. It wants to drain this wetland to grow cash crops. But it’s only because of the money you bring in that we are able to protect and enhance this national park: the Indian one-horned rhino, the Asiatic elephant, the tigers and all the other wildlife that’s here.’ So, it is a dilemma, but to stop that overnight would be disastrous for wildlife worldwide.

The pros, do out-weigh the cons – as long as we are sensible about it; we need to stop needless travel, we need to utilise public transport wherever we can, and in a rural area like mid Wales it’s often not even possible – more often than not I have to take the car. A change must come from individuals, but more than anything the change has got to come from government – we need a better public transport system.

Ecotourism can also provide sustainable jobs. I’ve just come back from Mull; the eagles bring in a huge amount of capital every year. Mull would probably grind to a halt without ecotourism. Yes, you have agriculture there and farming, but by far the biggest employer in Mull is green tourism. People come to Mull to see eagles, to see otters, to see minke whales, basking sharks, and all of these charismatic species. Morally, we shouldn’t have to put the economic argument forward, we should be looking after wildlife for its own sake. But when you are dealing with developers and ministers, you have to put the economic argument forward.

Are you a supporter of rewilding and do you think it is a sustainable use of land?

I am in principle, but say ‘rewilding’ to a lot of people and they say, “ah, they’re going to bring back wolves and bears, and I don’t want wolves and bears. My children will be mauled” etc. While that’s not true it’s also not true that’s what rewilding is all about. It’s really about the restoration of habitats, it is about what Isabella Tree and her husband have done at Knepp, which works fantastically well. Places like the Cambrian Mountains have fantastic wildlife like pine martens, goshawks, red squirrels etc, but vast areas of the Cambrian Mountains are a green desert. So, the potential for rewilding; just a few trees, maybe restoring the lost peat bogs etc. is vast and the knock-on effects for capturing carbon and preventing flooding all makes so much sense. But of course, the people in power want to make more money for themselves and their acquaintances and a lot of them don’t want to consider embracing this approach.

Does Brexit and the end of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) present any opportunities?

Firstly, I voted against Brexit, I think it will be an unmitigated disaster. It was the tabloid papers stirring the pot of xenophobia that prevented the real issues being properly discussed. Most of the farmers around me here voted for Brexit because they were fed up with what they saw as European bureaucracy. Of course, now the reality is biting, many farmers I speak to now wish they hadn’t, especially now as their MP has voted to allow cheap, low standard foods from the US into the country. Despite what we sometimes read, the food standards in the UK are very high and to lower those standards is stabbing farmers in the back.

However, in the long-term Brexit can offer an opportunity. If we had a better government in power, I would be optimistic about those opportunities because there is no doubt the CAP has been a most destructive policy from an environmental point of view. It really should have been reformed at least twenty years ago and now is an opportunity to do that, but with the current government’s track record with the environment makes me believe not much will change. We are up against a very powerful agricultural lobby. The big fertiliser companies, the big pesticide companies, the big machinery companies all of these are a massively powerful lobby and this government will listen to their argument not the environmentalist’s.

Has lockdown presented people with an opportunity to connect with nature?

I hear people saying how wildlife benefitted hugely from lockdown, and I think temporarily it did. One simple example is far fewer hedgehogs killed on the roads, of course now lockdown is eased I’m seeing dead hedgehogs on the roads all over again. Also, roadside verges not being mown or mowed late had a knock-on effect that was huge!! Flowers, bees, butterflies all in abundance. Some councils have seen this, taken note, and said – okay fantastic, we are going to reduce mowing from now-on. Others have carried on mowing and mowing, which is an absolutely dreadful policy for wildlife. Lockdown has really tested people, especially from a mental health point of view, but during lockdown the birds, flowers and butterflies have brought so much joy to families. Nature has been there for us through this traumatic time and we must remember that when these restrictions are over.

The one long term benefit I’m hoping lockdown will have is that a seed has been planted in a lot of youngsters and adults where they will think: remember last year when we walked this lane and there was all those flowers and we saw that lovely white and orange butterfly, let’s go and see if it’s all there again. So, hopefully for many people that seed has been planted.

Discover Iolo’s favourite ‘Wild Places’ in these two titles from Seren Books

Wild Places UK: The UK’s Top 40 Nature Sites

Wild Places UK: The UK’s Top 40 Nature Sites

By: Iolo Williams

Paperback | December 2019| £15.99 £19.99

From Hermaness on Shetland to the London Wetland Centre. Iolo Williams picks his favourite forty wildlife sites in the UK

Wild Places: Wales’ Top 40 Nature Sites

Wild Places: Wales’ Top 40 Nature Sites

By: Iolo Williams

Paperback | October 2016| £15.99 £19.99

Naturalist Iolo Williams picks his favourite forty from the many nature reserves throughout Wales

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

All photographs © Iolo Williams.

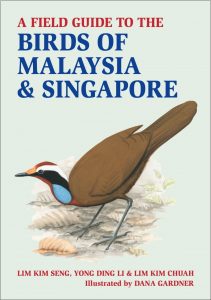

Kim Seng – My friend Dana Gardner, the illustrator of this book, got me interested in doing another book. We had successfully collaborated on a first field guide to the birds of Singapore in 1997 and were keen to work together again. Dana had a friend who was a publisher and we decided to a do a single volume field guide to the birds of the whole of Malaysia, since none existed. This was in 2010. Unfortunately, our publisher pulled out not long after that and we were left stranded. Luckily, through my fellow collaborators – Kim Chuah and Ding Li – we managed to get John Beaufoy interested in our project. A contract was signed in 2016 and as they say, the rest is history!

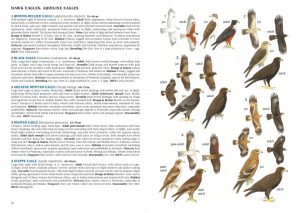

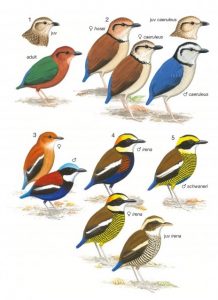

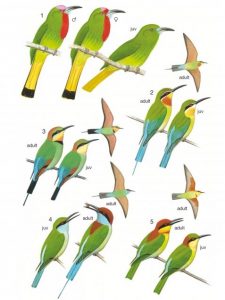

Kim Seng – My friend Dana Gardner, the illustrator of this book, got me interested in doing another book. We had successfully collaborated on a first field guide to the birds of Singapore in 1997 and were keen to work together again. Dana had a friend who was a publisher and we decided to a do a single volume field guide to the birds of the whole of Malaysia, since none existed. This was in 2010. Unfortunately, our publisher pulled out not long after that and we were left stranded. Luckily, through my fellow collaborators – Kim Chuah and Ding Li – we managed to get John Beaufoy interested in our project. A contract was signed in 2016 and as they say, the rest is history! Kim Seng – Each of us had different ideas on how to do the book and also other personal commitments. We as the writers also had to contend with differences in writing styles. Luckily, we decided to stick with a standard format, came up with a list of who was writing what chapters and what bird families and managed to more or less stick to our deadlines. Another challenge was the impressive work done by our illustrator. He had to do illustrations of all 829 species all by himself. To ensure accuracy, he would send us completed plates for comment, and we duly responded if changes were needed. Not an easy task, as we were based in Singapore and he, in the USA.

Kim Seng – Each of us had different ideas on how to do the book and also other personal commitments. We as the writers also had to contend with differences in writing styles. Luckily, we decided to stick with a standard format, came up with a list of who was writing what chapters and what bird families and managed to more or less stick to our deadlines. Another challenge was the impressive work done by our illustrator. He had to do illustrations of all 829 species all by himself. To ensure accuracy, he would send us completed plates for comment, and we duly responded if changes were needed. Not an easy task, as we were based in Singapore and he, in the USA. Kim Seng – Well, COVID-19 has placed tremendous restrictions on travel in both Malaysia and Singapore. You could bird in certain areas but only with social distancing and other safe practices in place. Initially, we could only look at the birds from our balconies or backyards but this was an opportunity for some of us to study some of the neglected urban birds and understand a little better. I actually published two blogs based on my observations of urban birds from my balcony! In the last couple of months, restrictions have been eased and we are allowed to go birding in our favourite birding places, but I’m still waiting for the day when I can travel freely and bird in Malaysia again.

Kim Seng – Well, COVID-19 has placed tremendous restrictions on travel in both Malaysia and Singapore. You could bird in certain areas but only with social distancing and other safe practices in place. Initially, we could only look at the birds from our balconies or backyards but this was an opportunity for some of us to study some of the neglected urban birds and understand a little better. I actually published two blogs based on my observations of urban birds from my balcony! In the last couple of months, restrictions have been eased and we are allowed to go birding in our favourite birding places, but I’m still waiting for the day when I can travel freely and bird in Malaysia again. Kim Seng – Three reasons – good birds, good food and good company. All three are never in short supply in these two amazingly friendly countries. The people are generally very friendly and the variety of local food is really incredible. Of course, the fascinating diversity of birds, with over 800 species of birds and Bornean, Peninsular and Sunda endemics in abundance are dreams to savour for birdwatchers and ornithologists alike.

Kim Seng – Three reasons – good birds, good food and good company. All three are never in short supply in these two amazingly friendly countries. The people are generally very friendly and the variety of local food is really incredible. Of course, the fascinating diversity of birds, with over 800 species of birds and Bornean, Peninsular and Sunda endemics in abundance are dreams to savour for birdwatchers and ornithologists alike.

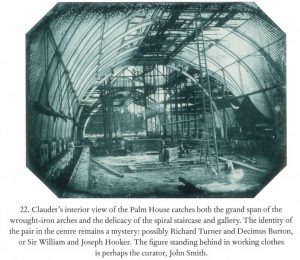

Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today

Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

Why were palms so important to the Victorians?

Why were palms so important to the Victorians? How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?

How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?