This book (or rather book series, since it will be more than just one book) has been an incredibly long time in the making, and the sheer scale of the project alone makes it a huge achievement. What were the main challenges you came across and how were they overcome?

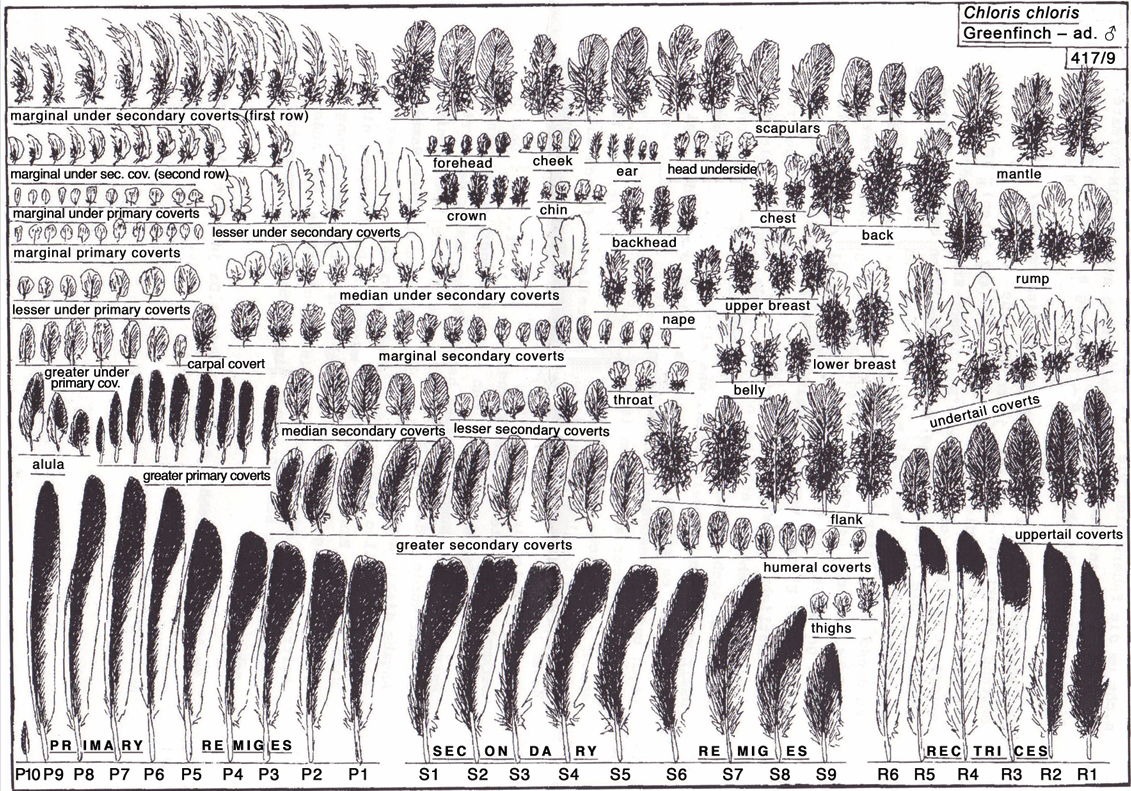

Our project began in 1998 when the French publisher Delachaux et Niestlé requested us to create a new feather identification guide based on colour photos. The illustrations of feathers in our Atlas are arranged according to a unique, recognisable pattern on a standardised grey background, each of them depicting the feathers of an individual bird, which allows readers to grasp the essence of different feather types at a glance. We use a method of directly scanning feathers on a flatbed scanner that was developed at the University of Amsterdam. But printing costs were prohibitive. Print-on-demand technology made it possible to produce smaller, more affordable print runs. We used this technology to produce our first collective work of the Feather Research Group titled The Tail Feathers of the Birds of Central Europe. We also produced two feather calendars with a series of colour plates that were composed for our Atlas of Feathers for Western Palearctic Birds as a test run to see how the colours came out in print.

In 2009, after 10 years of intense work, we produced a DVD with 1,280 colour plates featuring illustrations of feathers for 330 Passerine species. This compilation from many sources resulted in a wave of interest in our project. Meanwhile, the number of Passerine species for which colour plates were ready had nearly doubled to more than 600 species. We decided to publish our collective work under the name The Featherguide rather than any individual names. In this way, everyone in our group can identify with this eponym and no one needs to feel that anyone is adorning themselves with borrowed plumes.

The most time-consuming aspect of our work is the composition of feather images for bird species that are not found in any feather collections. Thanks to the kind support of the Feather Identification Laboratory at the Smithsonian Institution, and generous curators at Natural History Museums, it was possible to develop a technique that allows us to extract depictions of isolated feathers from photographs of bird skins. The missing part of the feather that remains in the skin is digitally added in a seamless way. A single colour plate produced in this way from many different puzzle pieces takes up to one week. With 1,350 bird species to be covered in our Atlas and our goal of illustrating all important plumages, you can imagine how many months and years this adds up to. We thank readers for their patience and interest.

Our project has inspired a number of off-shoots that will be welcome by most readers. For example, the French feather identification book by Cloé Fraigneau, which is now available under the title An Identification Guide to the Feathers of Western European Birds, emerged from the initial planning sessions we had with the director of Delachaux et Niestlé. The series of books on feather identification by Professor Hans-Heiner Bergmann was inspired by our flyer distributed at the International Ornithological Congress in 2006. A book titled Feathers: Displays of Brilliant Plumage by world–renowned photographer Robert Clark features several photographs of original feather sheets that were mounted for our Atlas of Feathers for Western Palearctic Birds, each depicted on a full double page. Even Audubon Magazine featured a series of photographs of original feather sheets from our Atlas of Feathers for Western Palearctic Birds. The Feather Atlas for North American Birds, published online by the Forensics Laboratory of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, was inspired by our original project description in the Conference Proceedings of the International Bird Strike Committee. The Featherbase website, which gets several million visitors per year, adopted the same grey background colour that we had chosen for our illustrations and also adopted the idea of depicting wing and tail diagrams in the way that we presented in our original project description.

The study of feathers has an obvious application for species identification, particularly when dealing with bird remains. But can a study of feathers also provide us with an insight into bird evolution and taxonomy, or indeed other areas of research?

Yes, indeed, much can be learned on these topics through the study of feathers. Subtle variations in the phenotype constitute the raw material for natural selection to act upon. Through the study of feathers, we can gain a deeper understanding of evolution. The high amount of phenotypic plasticity in bird wings is a clear example of evolution in progress. Many species exhibit subtle fluctuations in the extent and depth of emarginations on their primaries, resulting in different numbers of slots in their wings between different individuals. Another area of phenotypic plasticity is unusual variations in the number of flight-feathers. Our Feather Research Group compiled a large body of such variations from scientific literature and from our own research.

While feathers were not unique to birds, emarginations are. Birds as we know them today are thought to have evolved from Mesozoic stem birds that coexisted with feathered dinosaurs. The only line that survived the cataclysmic event on Yucatan 66 million years ago evolved emarginations in their wings. If we consider birds as a class of their own, then the feature that distinguishes birds from feathered dinosaurs is the presence of emarginations. The evolution of emarginations can bring clarity into today’s scientific discussion on the origin of birds, which largely portrays birds as living dinosaurs, thereby blurring the line between reptiles and birds. Emarginations make birds unique. Neither bats nor insects nor pterosaurs have emarginations in their wings. Not all bird families living today have emarginations in their wings, giving rise to the question whether these bird families never evolved emarginations or whether their emarginations disappeared during the course of evolution. Emarginations can be lost either through the evolution of very narrow, pointed wings or through devolution into flightlessness.

Whether our findings have any relevance for taxonomy is up to taxonomists to decide. In the past, taxonomy was entirely based on phenotype, while today it is largely based on genotype. Phenotypic variations do not play a significant role in current taxonomy, unless one is interested in the possible inheritance of epigenetic switches that regulate the expression of the genotype into the phenotype. For example, it is not clear whether the fine-tuning of the gradient in retinoic acid that is linked to two genes on the sixth and eighth chromosomes (and is responsible for the regulation of the vane width of feathers) was already inherent in the genome of Mesozoic stem birds and was activated through one of these epigenetic switches, giving rise to emarginations in modern birds. This question may be possible to answer by looking at the genome of bird families that appear to have never evolved emarginations so far, such as rails.

Who do you think these books will appeal to and who will benefit from such a comprehensive and high-quality atlas?

Anyone who visits the Featherbase website and finds the scans of feathers depicted there to be useful or interesting will also benefit from our work. If only 1% of the millions of visitors to this website see any value of having a printed Atlas with feather images of similar or even higher quality, this will make our Atlas of Feathers for Western Palearctic Birds worthwhile.

Many of the scans shown on the Featherbase website are from the collection of Dr. Wolf-Dieter Busching, the former director of the Naumann Museum in Köthen, Germany, who built up the largest scientific feather collection in the world, comprising feathers of around 2,500 bird species. During the time of the former communist regime in East Germany, it was difficult for Dr. Busching to obtain paper of a consistent colour for mounting the feathers in his collection. Therefore, his feather specimens are mounted on paper of many different colours, sometimes blue, sometimes red, sometimes yellow. Since the vanes of feathers are semi-transparent, the colour of the paper they are mounted on influences the colour of the feathers. In addition, the feathers in Dr. Busching’s collection often overlap each other, thereby hiding parts of the neighbouring feathers. In our Atlas of Feathers for Western Palearctic Birds, we show all feathers on the same standardised grey background and without overlap. In this way, each feather is fully visible and the colours of the feathers can be reliably compared.

Of course, the production of a series of books with high-quality colour plates is more expensive than running a website. The cost of such a series in printed form will limit the number of potential buyers compared to the number of visitors to the Featherbase website. We will keep the cost as low as possible to maximise the number of people able to afford our series in printed form.

The first volume in the series provides readers with a global overview of feather characteristics. Were there any particularly surprising data or revelations that resulted from compiling such a comprehensive collection?

There were several surprises indeed. Two of the most peculiar discoveries, or rather rediscoveries, were made in the families Tityridae (tityras, becards and allies) and in the family Trochilidae (hummingbirds). In the families Tityridae, two genera, Tityra and Pachyramphus, have a small, crippled primary number 9 in between normally-sized neighbours in the wings of adult males, while females and juveniles have normally formed wings. The function of the reduced-sized P9 may be related to sound production (sonation) during the display of adult males, but so far, we could not find any references in the scientific literature that would substantiate such an assumption. Amazingly, this peculiar phenomenon had even escaped the attention of Dr. Wolf-Dieter Busching, who devoted his entire life to the study of feathers, and none of our other collaborators in the Feather Research Group noted this phenomenon.

There are currently three mounted feather specimens of adult males of these two genera on the internet, one of them from the collection of Dr. Busching and two from other feather collections. In each of these three feather collections, the reduced-size P9 was mistakenly glued in front of P10 rather than in its correct position between P8 and P10, indicating that the respective feather researchers had no clue where this feather belongs and seem to have misjudged it to be a reduced outer primary, as is found in many passerines. However, when we consulted an older publication on feathers from 136 years ago, it turns out that this odd, reduced-size feather was already noted by Hans Gadow in 1888, at least in the genus Tityra, while its presence in the genus Pachyramphus seems to have escaped his attention, too.

The second peculiar discovery in the family of hummingbirds concerns the presence of emarginations at the tips of the outer primaries in males of 22 species from five genera. Most of us in the Feather Research Group had assumed by default that none of the hummingbird species have any emarginations, based on our experience with the many species for which we had examined feathers. The great majority of the 377 extant hummingbird species do not have any emarginations, as in the related family of swifts. So, it would have been easy to miss these exceptional few species if the effort had not been made to look at every single hummingbird species based on photographs of live birds. Again, the fact that only males of these exceptional species have emarginations, while females are missing them, leads to the assumption that these emarginations have something to do with the display flight of males. In this case, there is indeed a scientific paper dating back to 1983, which confirms this assumption for just one of the 22 hummingbird species in which males have emarginations. The only feather experts who knew about this study are Professor Lukas Jenni and Dr. Raffael Winkler from Switzerland. The authors of this study found that males create noises with their emarginated primaries and that these noises are used to protect nectar resources. Filling the slot between emarginated primaries with a glue film or clipping the distal 2–3 mm of these primaries caused males to sing more to protect their territories. We can deduce that the other hummingbird species in which males have emarginations use them in a similar way to produce sound. There is, however, a sixth genus of hummingbird in which males have inverse emarginations at the base of the primaries, not at their tips. This phenomenon of emarginations at the feather bases instead of at their tips does not make any aerodynamic sense, so it is likely that these inverse emarginations have some type of ornamental function in males.

These two discoveries, or rather rediscoveries, in the families Tityridae and Trochilidae teach us to remain open and not adhere to preconceived ideas. They also teach us to consult old literature that may have been forgotten or considered outdated.

The first volume will initially be published in black and white to make it affordable to as many people as possible. The online database of feathers is also available to everyone in the hopes that citizen scientists and members of the public will help to verify and correct the results. Given that birdwatching is such a popular pastime, do you think that there is a large body of untapped knowledge within the birding public?

There definitely is a large body of untapped knowledge within everyone, not only within the birding community. The key is to allow everyone to express their inner potential themselves. We are in favour of encouraging birders to publish their own data under their own names. Professor Peter Finke, who advises our Feather Research Group, calls this approach of empowering citizens to publish their own data Citizen Science Proper. What has been prevalent so far is Citizen Science Light, in which so-called experts scoop off the knowledge of the public and make a name for themselves with borrowed plumes, so to speak. Professor Finke published a book titled Citizen Science: The Underestimated Knowledge of Laymen (, which answers this question in much greater depth, giving many examples for birdwatchers in particular.

With regards to the global survey of emarginations in all bird species of the world, that became possible on the basis of photographs of live birds, which citizen scientists generously share on the internet. Our approach of opening our research findings on the number of emarginations in all bird species of the world by listing the internet links of the original photos that were used for this study is a way of thanking these many thousands of photographers. They all deserve to be mentioned as co-authors of our study. By sharing our findings and providing the original links to the photos that were used, we offer these photographers a way to give us their feedback on what we discovered thanks to their generosity. Anyone else who likes to share their observations on the photographs of live birds and scans of feathers that were used for our study is also welcome. We greatly value this interaction with birdwatchers and the general public.

How many volumes will the series eventually comprise, and do you know when they are due to be published?

After our last meeting in 2016, the World Feather Atlas Foundation purchased ten large scanners for our Feather Research Group. Five of these scanners went to the Featherbase team to support their endeavour of creating a World Feather Atlas. The remaining five were given to other collaborators in our group. The Featherbase team adopted the same grey background for newly mounted feather specimens as we adopted in 1998 for our Atlas of Feathers for Western Palearctic Birds. This unified the backgrounds on all scans, creating the basis for a potential cooperation to speed up the work on our Atlas of Feathers for Western Palearctic Birds.

The production of colour plates for the passerines took 24 years because they were all produced by only one person. If the work on the colour plates for the non-passerines is divided up by the holders of these ten scanners, it will be possible to produce the remaining colour plates more quickly. At the same time, the holders of these scanners can use them for their own projects.

Most important to us is to respect the copyrights of everyone who produces scans of feathers. Any contributions to our Atlas of Feathers for Western Palearctic Birds must be based on mutual respect for everyone’s free will. Those who contribute scans of feathers are treated at an equal level to those who contribute text. In the past, illustrators of bird guides were often underappreciated compared to the authors. All too often, illustrators were not even mentioned on the book cover. We feel that this relationship between illustrators and authors needs to be amended. Illustrators deserve to be cited alongside authors. In our Atlas of Feathers for Western Palearctic Birds, the work of those who produce scans of feathers is even more important than those who write the texts, because the texts can only be written on the basis of these scans.

The Full Edition of our Atlas of Feathers for Western Palearctic Birds will comprise a total of ten volumes including the introductory volume. Each of the subsequent nine volumes will cover about 150 bird species, adding up to a total of about 1,350 bird species. The Concise Edition will consist of two volumes. . The most precious thing we have to offer are the large-size colour plates in the full edition. The illustrations of feathers in the Concise Edition will be a cut-down version of the original colour plates and considerably smaller.

Atlas of Feathers for Western Palearctic Birds, Volume 1: Introduction is available to pre-order from our online bookstore.

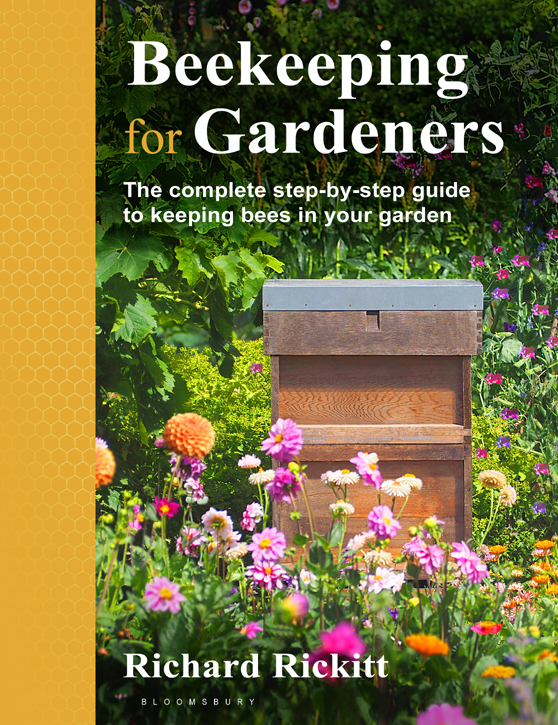

Richard Rickitt is an award-winning author as well as co-editor of the UK’s best-selling beekeeping magazine

Richard Rickitt is an award-winning author as well as co-editor of the UK’s best-selling beekeeping magazine

Join author Kat Hill on a journey across England, Scotland and Wales to explore 15 remote bothies, and uncover the beauty, history and stories of these wild shelters. In this stirring book of adventure, peace, wilderness and refuge, she intertwines her own story of heartbreak and new purpose, while taking into consideration the environment, what we owe to it, and why we all crave escapes into the remote.

Join author Kat Hill on a journey across England, Scotland and Wales to explore 15 remote bothies, and uncover the beauty, history and stories of these wild shelters. In this stirring book of adventure, peace, wilderness and refuge, she intertwines her own story of heartbreak and new purpose, while taking into consideration the environment, what we owe to it, and why we all crave escapes into the remote.

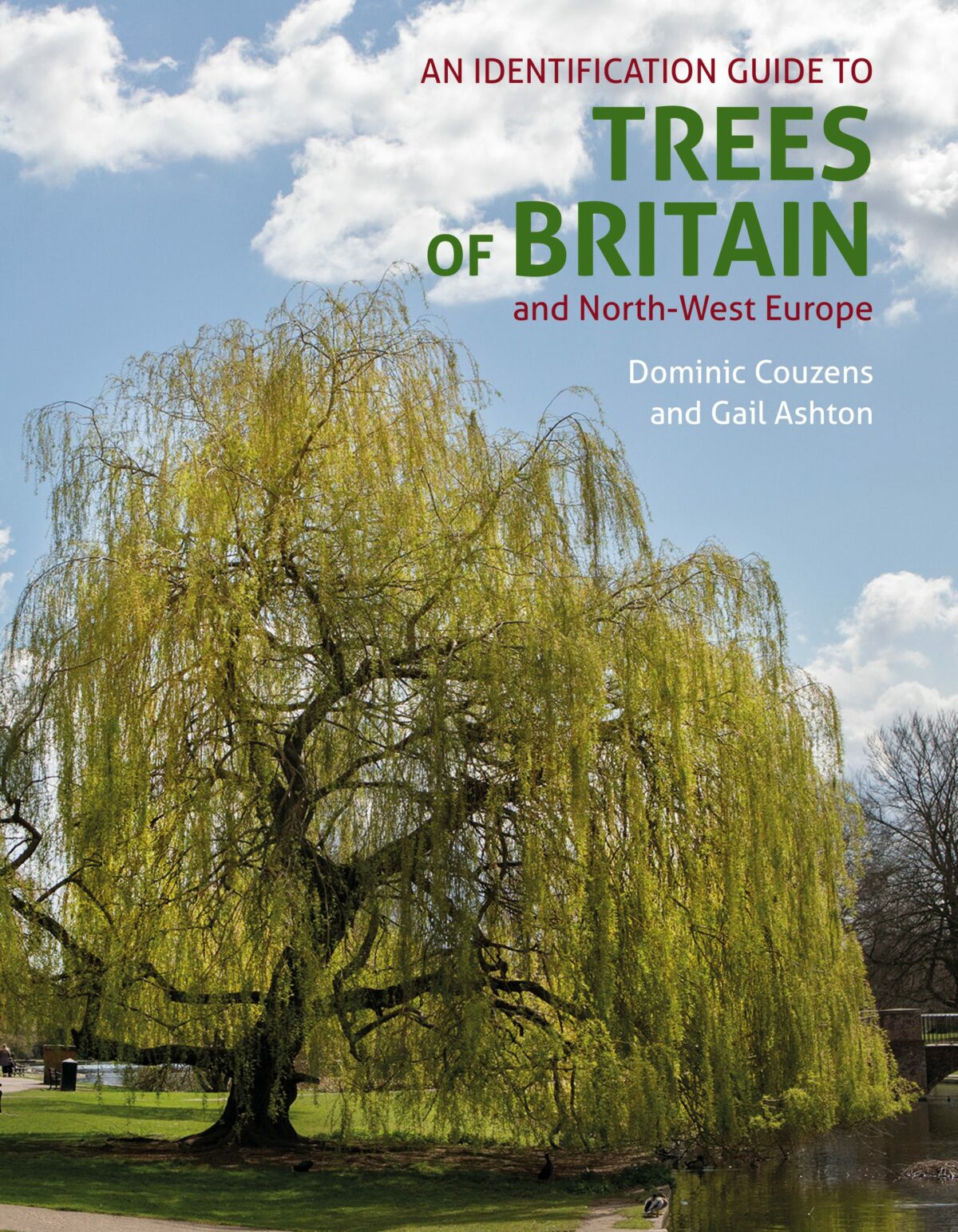

Dominic Couzens is a bird expert, nature writer and the author of over 40 books. He is also a regular print columnist and writes for Bird Watching Magazine, Nature’s Home (RSPB) and Water Life (WWT). He is passionate about communicating about the natural world and has a particular passion for writing about current threats to the planet and how they can be best addressed.

Dominic Couzens is a bird expert, nature writer and the author of over 40 books. He is also a regular print columnist and writes for Bird Watching Magazine, Nature’s Home (RSPB) and Water Life (WWT). He is passionate about communicating about the natural world and has a particular passion for writing about current threats to the planet and how they can be best addressed. Gail Ashton is a photographer and writer with a passion for wildlife and invertebrates in particular. Well known for an incredible project where she undertook to photograph 500 UK invertebrates over the course of a year, she is passionate about encouraging everyone, young or old, to observe and appreciate the natural world.

Gail Ashton is a photographer and writer with a passion for wildlife and invertebrates in particular. Well known for an incredible project where she undertook to photograph 500 UK invertebrates over the course of a year, she is passionate about encouraging everyone, young or old, to observe and appreciate the natural world.

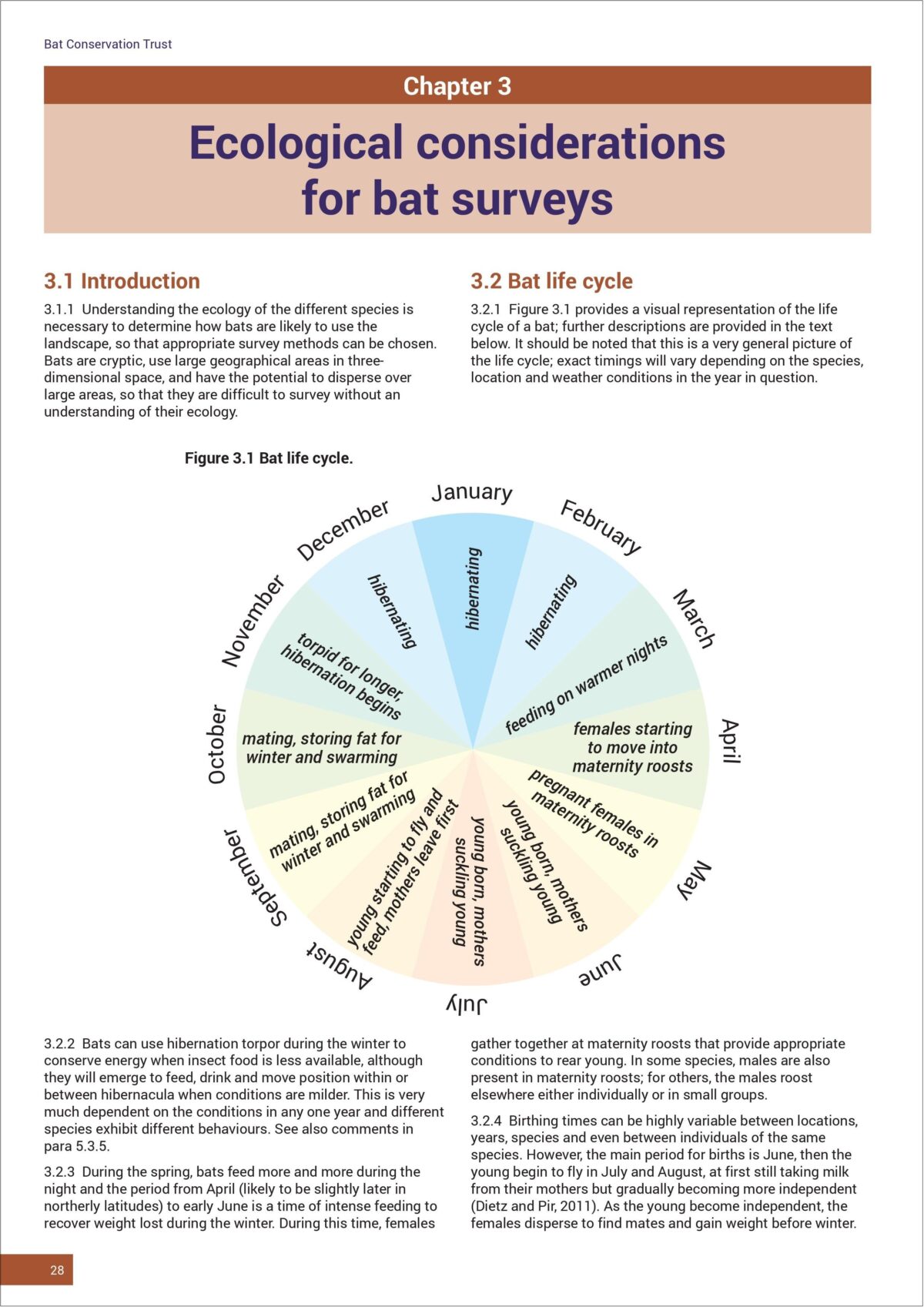

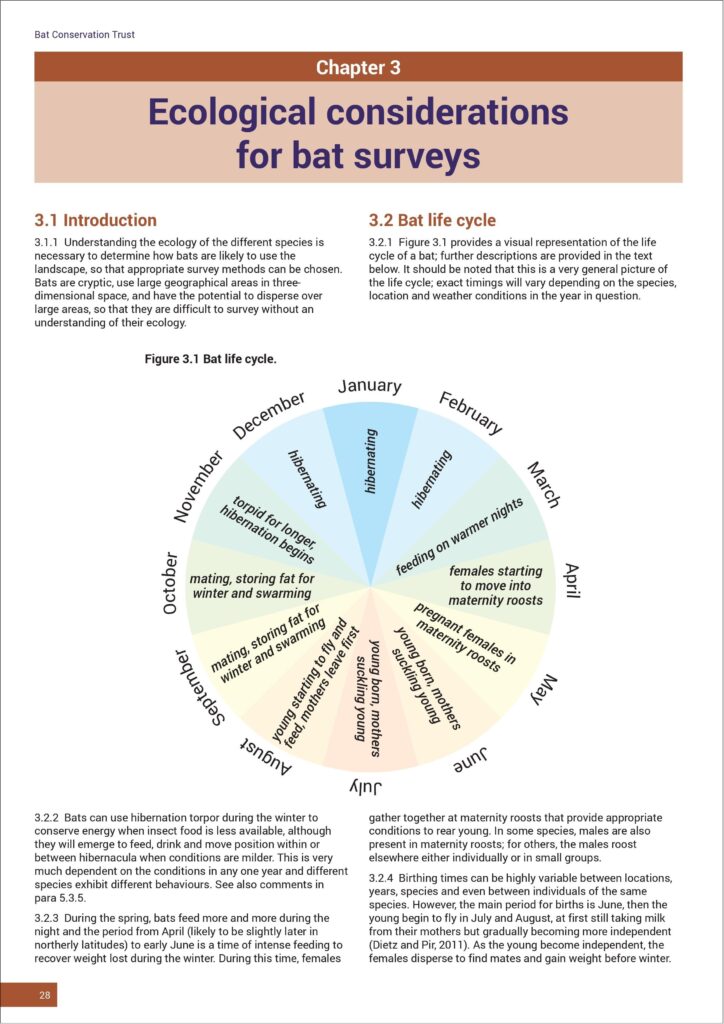

Broadly speaking, these Good Practice Guidelines are what we all need to be referring to now for guidance and, barring any new properly released formal material direct from BCT (i.e. it doesn’t matter what someone says on a social media post or during a webinar) that either updates, changes or gives additional explanation to what is in the 4th edition, this is where we, as a community, are at. BCT have confirmed that a few changes to the text will be made by way of an amendment document and this, in conjunction with printed Q&A material resulting from BCT webinars (November 2023 and February 2024), will prove to be essential complimentary reading for everyone relying upon these guidelines during their day-to-day work.

Broadly speaking, these Good Practice Guidelines are what we all need to be referring to now for guidance and, barring any new properly released formal material direct from BCT (i.e. it doesn’t matter what someone says on a social media post or during a webinar) that either updates, changes or gives additional explanation to what is in the 4th edition, this is where we, as a community, are at. BCT have confirmed that a few changes to the text will be made by way of an amendment document and this, in conjunction with printed Q&A material resulting from BCT webinars (November 2023 and February 2024), will prove to be essential complimentary reading for everyone relying upon these guidelines during their day-to-day work. I mention this for two reasons. Firstly, it’s what I feel almost everyone was genuinely expecting. Secondly, these revised guidelines don’t (as anticipated rightly or wrongly!) fully address some of the specific aspects of where the NVA debate is going to finally arrive. Regarding this aspect of bat work, the finer detail around this matter is now being tackled by a review panel, and BCT will inform us as/when they are in a position to do so. In the meantime, the Interim Guidance (2022) remains as an additional, essential point of referral. Having said that, within these new guidelines there are regular pointers, reminders and requirements that NVAs should be incorporated within survey design.

I mention this for two reasons. Firstly, it’s what I feel almost everyone was genuinely expecting. Secondly, these revised guidelines don’t (as anticipated rightly or wrongly!) fully address some of the specific aspects of where the NVA debate is going to finally arrive. Regarding this aspect of bat work, the finer detail around this matter is now being tackled by a review panel, and BCT will inform us as/when they are in a position to do so. In the meantime, the Interim Guidance (2022) remains as an additional, essential point of referral. Having said that, within these new guidelines there are regular pointers, reminders and requirements that NVAs should be incorporated within survey design. From a business owner’s perspective there are matters that will need serious consideration and budgeting for. This could impact (again negatively or positively) upon your turnover, your approach to tendering, resourcing, the deployment of staff and equipment, as well as the careful balancing of your team’s time at their desks versus time in the field. All of this, of course, needs to be considered against the benefits to bat conservation. The challenge on the business model is not necessarily a bad thing, provided you are fore-armed and have seriously thought through how these changes impact upon your organisation.

From a business owner’s perspective there are matters that will need serious consideration and budgeting for. This could impact (again negatively or positively) upon your turnover, your approach to tendering, resourcing, the deployment of staff and equipment, as well as the careful balancing of your team’s time at their desks versus time in the field. All of this, of course, needs to be considered against the benefits to bat conservation. The challenge on the business model is not necessarily a bad thing, provided you are fore-armed and have seriously thought through how these changes impact upon your organisation.