***** An eye-opening and thought-provoking reportage

The road to hell might be paved with good intentions, but the roads to pretty much everywhere else are paved with the corpses of animals. In Crossings, environmental journalist Ben Goldfarb explores the outsized yet underappreciated impacts of the ~65 million kilometres of roads that hold the planet in a paved stranglehold. These extend beyond roadkill to numerous other insidious biological effects. The relatively young discipline of road ecology tries to gauge and mitigate them and sees biologists join forces with engineers and roadbuilders. This is a wide-ranging and eye-opening survey of the situation in the USA and various other countries.

The road to hell might be paved with good intentions, but the roads to pretty much everywhere else are paved with the corpses of animals. In Crossings, environmental journalist Ben Goldfarb explores the outsized yet underappreciated impacts of the ~65 million kilometres of roads that hold the planet in a paved stranglehold. These extend beyond roadkill to numerous other insidious biological effects. The relatively young discipline of road ecology tries to gauge and mitigate them and sees biologists join forces with engineers and roadbuilders. This is a wide-ranging and eye-opening survey of the situation in the USA and various other countries.

As Goldfarb points out, roadkill is as old as the road but the phenomenon went into overdrive with the invention of the combustion engine and a new-found need for speed that menaced humans and animals alike. With the morbid curiosity typical of biologists, Dayton and Lilian Stoner published the first tally of motorcar casualties in 1925, in the process diagnosing “a malady with no name” (p. 16), as the word roadkill would not be coined for another two decades. The word road ecology was only coined in 1993 by Richard Forman, though it was translated from the German Straßenökologie that was coined in 1981 by Heinz Ellenberg.

As a discipline, road ecology both studies the impact of roads and formulates solutions. Particularly common, and featured extensively in this book, are wildlife crossings. Underpasses serve many animals but others have different needs such as overpasses or canopy rope bridges. Amphibians and reptiles are given a helping hand with toad tunnels and bucket brigades. Fish migration is being restored by retrofitting culverts that are better navigable.

To us, roads are the unnoticed connective tissue that links places of extraction with industry and commerce, and shuttles commuters between home and work. For other animals, they are barriers: despite the good intentions, wildlife crossings cannot serve all animals equally and cannot be constructed everywhere. Millions of animals still die in collisions every day. Goldfarb addresses the very real concerns of extirpation, habitat fragmentation, interrupted migrations, and noise pollution. With roads come humans who bring deforestation, hunting, real estate development, urban sprawl, tourism, etc.

Amidst this litany of harms, Goldfarb features several topics that will be eye-opening even to ecologists. There is the little-known history of how the US Forest Service constructed one of the world’s largest road networks of now mostly abandoned forest tracks. Roads also feed a diverse community of scavengers that includes humans; a necrobiome that “airbrushes our roadsides, camouflaging a crisis by devouring it” (p. 181). In Syracuse, Goldfarb faces the racist legacy of interstate highways that were bulldozed straight through Black and Latino neighbourhoods. Plans are now afoot to reverse this wrong, move the highway, and create a community where people can again walk to their destinations. In a brilliant flourish, Goldfarb connects this back to the book’s main topic: “Road ecologists and urban advocates are engaged in the same epic project: creating a world that’s amenable to feet” (p. 287).

So far, so good. Goldfarb’s writing shines and certain turns of phrase are memorable. I was initially concerned how US-centric this book would be. Though weighted towards US examples, Goldfarb also visits Wales, Costa Rica, Tasmania, and Brazil, and discusses several European initiatives.

Despite the gloomy picture, there are some encouraging signs. The US Forest Service has started decommissioning parts of its road network. Brazil, meanwhile, shows what government regulation can achieve. Here, highway operators are held legally responsible for dealing with the harm and costs resulting from collisions. Contrast this with the USA, Goldfarb observes sharply, where individual drivers are blamed for collisions. This “deflects culpability from the car companies building ever more massive SUVs and the engineers designing unsafe streets” (p. 295). As with addressing climate change, individual action only gets us so far; making roads safer demands systemic change, “a public works project, one of history’s most colossal” (p. 296).

And yet, something nagged at me. The focus on mitigation smacks of a palliative solution and Goldfarb concedes the limitations of road ecology. Crossings and fences will not stop the many other impacts of roads and risk becoming “a form of greenwashing […] a fig leaf that conceals and rationalizes destruction” (p. 265). As with other environmental problems, should we not first focus on abandoning or reducing certain behaviours, instead of turning to techno-fixes? Can we imagine something more radical? Can Goldfarb?

To his credit, he admits wrestling with this problem. “The most straightforward solution to the road’s ills would be a collective rejection of automobility […] In the course of writing this book, I’ve felt, at times, like a defeatist—as though, by extolling wildlife passages, I foreclose the possibility of a more radical, carless future” (p. 295). I would have loved to see him explore this further in a dedicated chapter. Instead, Goldfarb comes down on the side of pragmatism. Bicycles and public transport are great for making urban areas more liveable, but most roadkill happens elsewhere. Furthermore, personal mobility is only part of the story, with logistics making up a huge chunk of traffic. The eye-opening chapter on Brazil, and the outsized influence of China’s Belt and Road Initiative that sees it invest in infrastructure globally, is a forceful reminder that the developmental juggernaut is nigh impossible to slow down. One road ecologist points out that you cannot seriously enter the discussion around roads if you oppose social and economic development, while another chimes in that, whether we like it or not, more roads will be built. Although I do not think resistance is futile, Goldfarb leaves me sympathetic to the road ecologists who are desperately trying to nudge construction projects in directions “that, if not quite “right,” are at least less wrong” (p. 270).

Goldfarb acknowledges the input of some 250 people and even then stresses his book is far from the final word on the subject. He encourages readers to take it as a starting point and read deeper, providing 43 pages of notes to the many sources of information he has used. I would additionally recommend A Clouded Leopard in the Middle of the Road by Australian road ecologist Darryl Jones which was published last year but seems to have flown under the radar compared to Goldfarb’s book. Overall, Crossings is a wide-ranging, eye-opening, and thought-provoking reportage that deserves top marks.

Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Chapter 3 bundles together research on numerous other senses, including ones familiar (smell, taste, and hearing) and unfamiliar to us (perception of polarised light, Earth’s magnetic field, and electric fields). The antennae of bees, in particular, are marvels; Chittka likens them to a biological Swiss army knife, packing numerous different sense organs into two small appendages. Tightly connected to sensory biology is how this incoming information is processed in the brain, though Chittka postpones discussing neurobiology to chapter 9. He describes the discovery and function of different brain areas and highlights the work of Frederick Kenyon who would inspire the better-remembered Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Thanks to them, we now understand that brains consist of numerous specialised nerve cells. Though the bee brain is small, Chittka argues that size is a poor predictor of cognitive skills; it is the wiring of neurons that matters. Rather than be surprised that small-brained insects such as bees can do so many clever things, Chittka instead tickles the reader with the opposite question: “Why does any animal need as large a brain as a bee’s?” (p. 153).

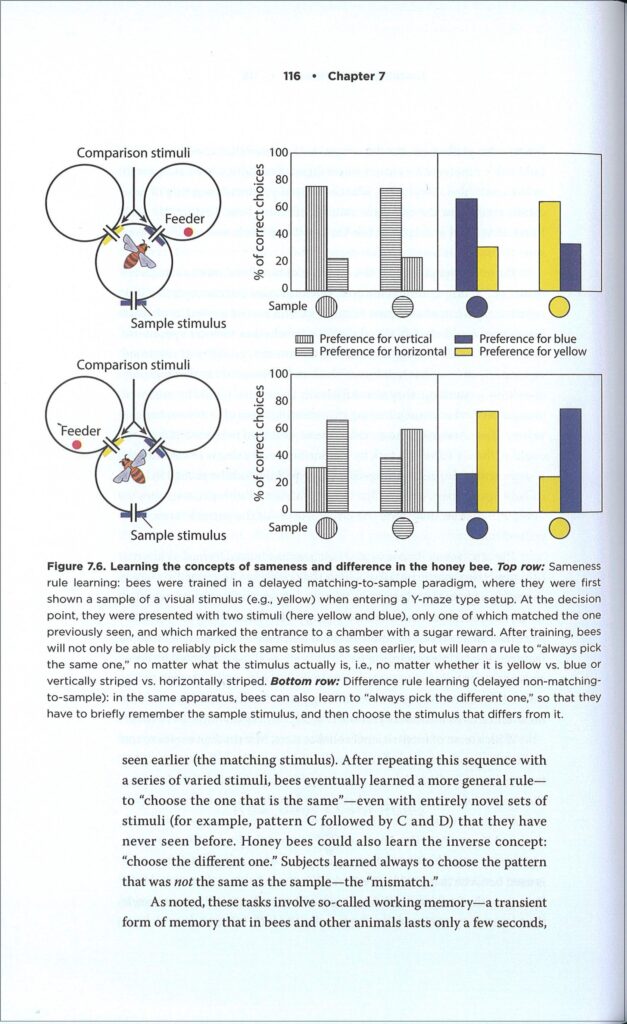

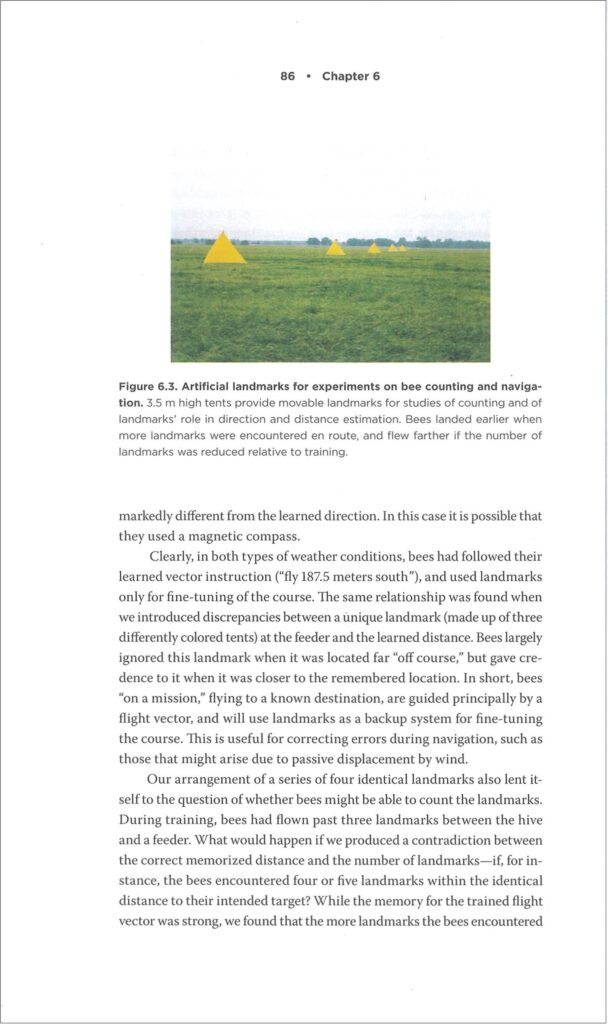

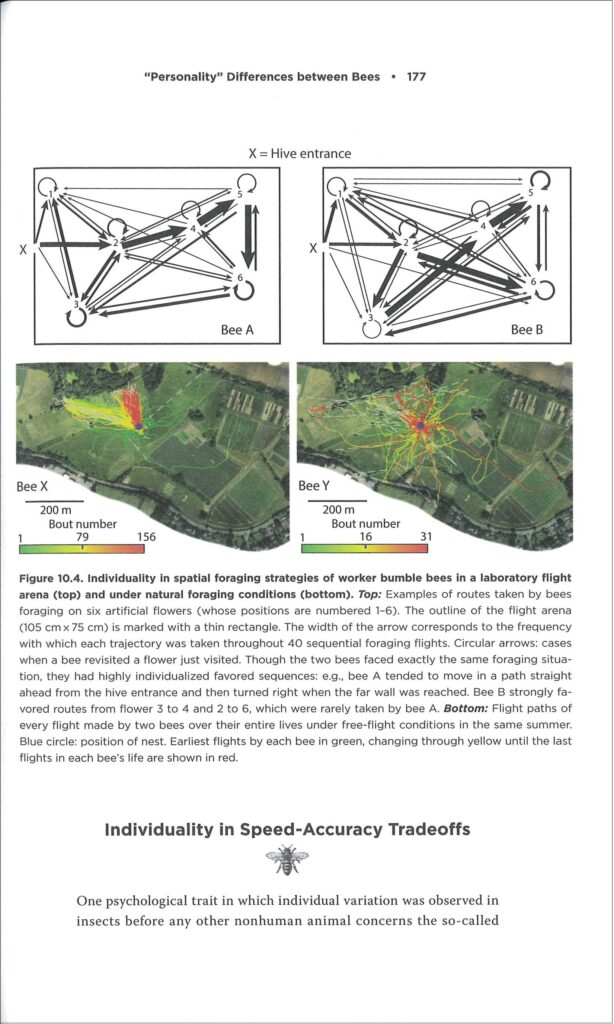

Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Chapter 3 bundles together research on numerous other senses, including ones familiar (smell, taste, and hearing) and unfamiliar to us (perception of polarised light, Earth’s magnetic field, and electric fields). The antennae of bees, in particular, are marvels; Chittka likens them to a biological Swiss army knife, packing numerous different sense organs into two small appendages. Tightly connected to sensory biology is how this incoming information is processed in the brain, though Chittka postpones discussing neurobiology to chapter 9. He describes the discovery and function of different brain areas and highlights the work of Frederick Kenyon who would inspire the better-remembered Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Thanks to them, we now understand that brains consist of numerous specialised nerve cells. Though the bee brain is small, Chittka argues that size is a poor predictor of cognitive skills; it is the wiring of neurons that matters. Rather than be surprised that small-brained insects such as bees can do so many clever things, Chittka instead tickles the reader with the opposite question: “Why does any animal need as large a brain as a bee’s?” (p. 153). What clever things do bees do, you ask? That is the subject of the preceding five chapters where Chittka surveys a large body of behavioural research. Honey bees are famous for their waggle dance by which they communicate the location of flowers but also, this was news to me, the location of potential nest sites when the swarm relocates. But Chittka discusses more, much more: how bees navigate space using landmarks, show a rudimentary form of counting, solve the travelling salesman problem, learn to extract nectar from complex flowers, learn when to exploit certain flowers (and when to ignore them), and learn new tricks by observing other bees. But what about instinct, something most behaviours were traditionally ascribed to? He has some insightful comments on this: “even the most elemental behavior routines need to be refined by learning: instinct provides little more than a rough template” (p. 50). What really made me fall off my chair is that bees have long been outsmarting researchers in choice experiments. Many behavioural experiments take the form of choice tests, where bees need to pick between two locations or objects that differ in e.g. colour or shape with one option containing a sugary solution as a reward. Bumblebees would simply be lazy and check out both options in random order. Until, that is, protocols were modified by adding a bitter-tasting solution to the wrong choice as a penalty.

What clever things do bees do, you ask? That is the subject of the preceding five chapters where Chittka surveys a large body of behavioural research. Honey bees are famous for their waggle dance by which they communicate the location of flowers but also, this was news to me, the location of potential nest sites when the swarm relocates. But Chittka discusses more, much more: how bees navigate space using landmarks, show a rudimentary form of counting, solve the travelling salesman problem, learn to extract nectar from complex flowers, learn when to exploit certain flowers (and when to ignore them), and learn new tricks by observing other bees. But what about instinct, something most behaviours were traditionally ascribed to? He has some insightful comments on this: “even the most elemental behavior routines need to be refined by learning: instinct provides little more than a rough template” (p. 50). What really made me fall off my chair is that bees have long been outsmarting researchers in choice experiments. Many behavioural experiments take the form of choice tests, where bees need to pick between two locations or objects that differ in e.g. colour or shape with one option containing a sugary solution as a reward. Bumblebees would simply be lazy and check out both options in random order. Until, that is, protocols were modified by adding a bitter-tasting solution to the wrong choice as a penalty. As mentioned above, this book is focused. If you enjoy reading about the facts and the study system with minimal (autobiographical) diversions, Chittka has got you covered. The only digression he allows himself is to include biographical details of older generations of scientists. This includes inspiring tales such as Karl von Frisch who described the honey bee waggle dance and later barely escaped being dismissed from his post by the Nazis. And look out for repeat appearances of Charles Turner, a now largely forgotten African American scientist who published pioneering work despite having been denied a professorship based on his ethnicity. But there are also tragic stories such as Kenyon’s, who snapped under pressure of not securing a permanent job and was incarcerated in a lunatic asylum where he died more than 40 years later, alone and forgotten. Chittka includes occasional quotations from historical literature to show that “many seemingly contemporary ideas about the minds of bees had already been expressed, in some form, over a century ago” (p. 15).

As mentioned above, this book is focused. If you enjoy reading about the facts and the study system with minimal (autobiographical) diversions, Chittka has got you covered. The only digression he allows himself is to include biographical details of older generations of scientists. This includes inspiring tales such as Karl von Frisch who described the honey bee waggle dance and later barely escaped being dismissed from his post by the Nazis. And look out for repeat appearances of Charles Turner, a now largely forgotten African American scientist who published pioneering work despite having been denied a professorship based on his ethnicity. But there are also tragic stories such as Kenyon’s, who snapped under pressure of not securing a permanent job and was incarcerated in a lunatic asylum where he died more than 40 years later, alone and forgotten. Chittka includes occasional quotations from historical literature to show that “many seemingly contemporary ideas about the minds of bees had already been expressed, in some form, over a century ago” (p. 15).