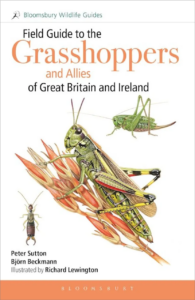

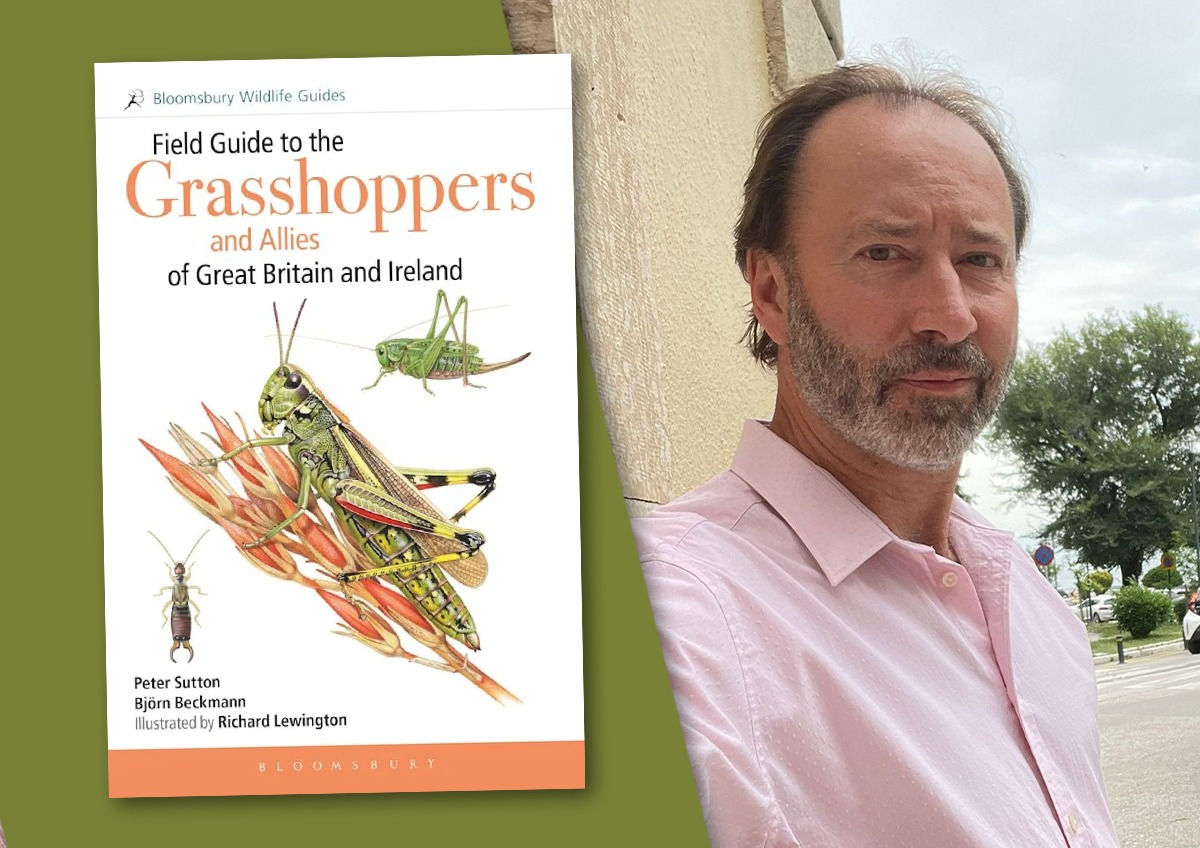

The Bloomsbury Wildlife Guides series has consistently set the standard for invertebrate identification, combining practical, readable text with meticulous illustrations by Richard Lewington. The latest instalment tackles the grasshoppers and relatives, a diverse and fascinating group undergoing rapid change in Britain. With flawless production quality and clever features such as QR links to audio recordings, this book provides a complete picture of the identification and dynamic lives of these fascinating insects.

The Bloomsbury Wildlife Guides series has consistently set the standard for invertebrate identification, combining practical, readable text with meticulous illustrations by Richard Lewington. The latest instalment tackles the grasshoppers and relatives, a diverse and fascinating group undergoing rapid change in Britain. With flawless production quality and clever features such as QR links to audio recordings, this book provides a complete picture of the identification and dynamic lives of these fascinating insects.

We recently had the pleasure of speaking to author Peter Sutton about the story behind the book, changes in the British fauna, and what readers can expect from the new guide.

How long have you been studying these insects and what first led you to take an interest in them?

I have been studying this group of insects since I began to catch grasshoppers half a century ago at the age of seven, on a dry grass verge that ran alongside a railway line in West Sussex. I was drawn to them by their song, their amazing ability to jump and fly, and the bright orange-red abdomen of the males. This led, in a bramble thicket at the same site, to my first sighting of bush-crickets, and then on to learning about all of the British species when I found Dr David Ragge’s Grasshoppers, Crickets and Cockroaches of the British Isles at Crawley Town library. It was this authoritative and fascinating text that informed all future journeys to the New Forest, the Isle of Purbeck, Chesil Beach, and anywhere else that was likely to reveal the orthopteran riches of these islands.

How did the new field guide come about?

I first had conversations with Andrew Branson who floated the idea of a field guide almost 20 years ago. At the time, this potential project was put on hold because there was a lot of activity by other writers who were working on publications about the Orthoptera. However, it soon became clear that there was a genuine requirement for a publication that covered all of the orthopteroid insects including the earwigs, stick-insects, cockroaches and mantids. Björn Beckmann and I were busy working on an updated distribution atlas when we got the call from Bloomsbury saying that Richard Lewington had agreed to illustrate a field guide for this group of insects. With a bit of further negotiation, we arranged for the field guide to include distribution maps for all of the native species, as well as naturalised species that had established viable outdoor colonies, and with this agreed format, the project went ahead.

Can you give us a taste of what’s covered within the species accounts and elsewhere in the guide?

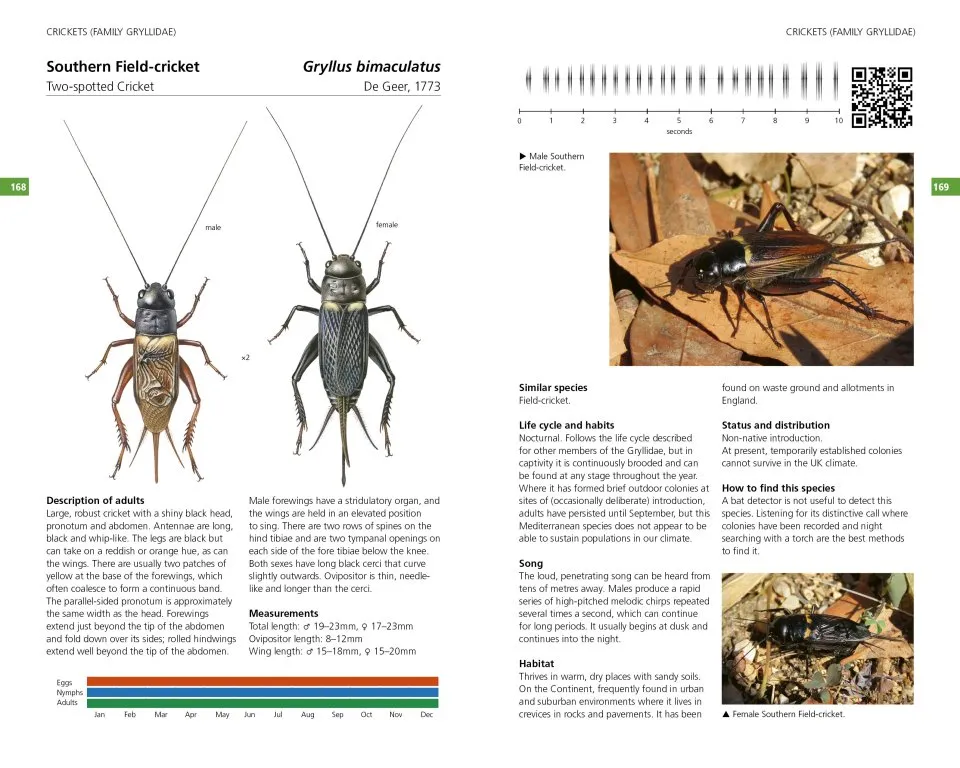

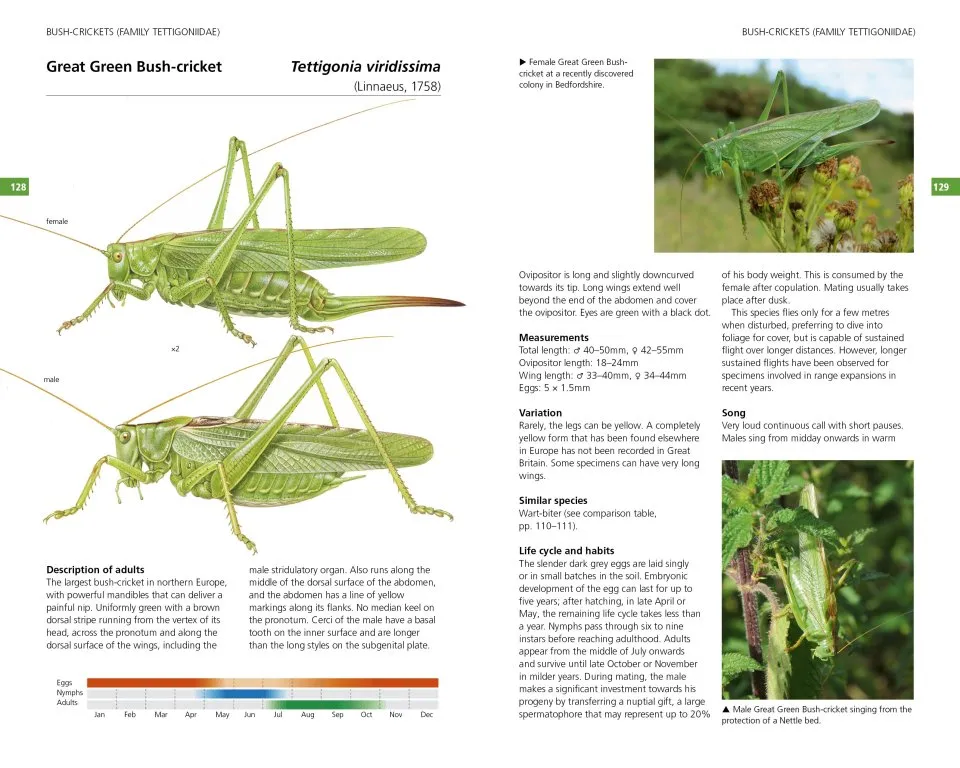

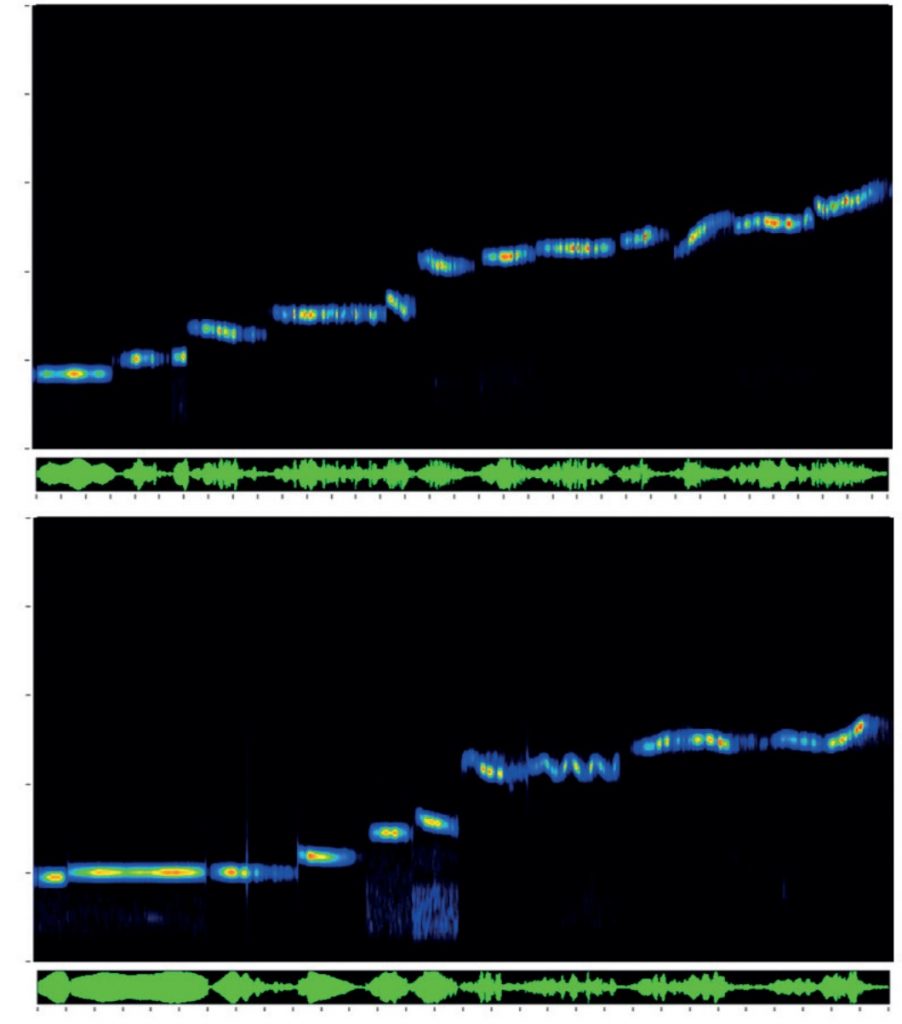

The 65 species accounts have the following format: a detailed Description of adults highlighting key identification features; Measurements (total length, wing length, ovipositor/cerci length, eggs/ootheca size); Variation (colour and pattern forms/wing length; Similar species; Lifecycle and habits including colour-coded phenology charts; a description of Song including a visual representation (sonogram) and a QR code that allows the reader to hear the song when scanned using mobile phone technology; Habitat and distribution (including, the 48 for native and outdoor naturalised species, a small generalised map in the account and a detailed 10km square map in the appendix); Conservation (for species that have IUCN threat status); and details of How to find this species. These accounts also include illustrations of male and female adults and where useful, nymphs, as well as additional photographs of adults, nymphs, and varieties.

A comprehensive and well-illustrated Introduction (over 300 photographs have been used to illustrate this field guide) is followed by chapters on Studying and recording orthopteroid insects, and a Regional guides section written by county and regional recorders, which provides an assessment of species that are likely to be found in Great Britain and Ireland, including the Channel Islands, Isles of Scilly, and the Isle of Man.

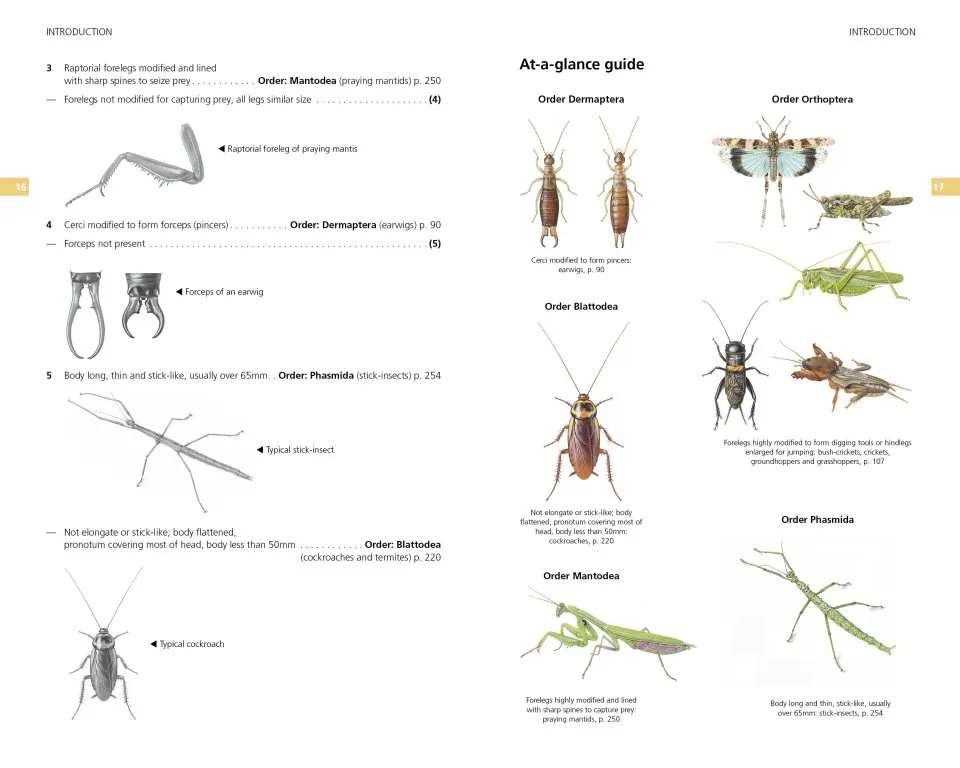

An illustrated ‘At-a-glance’ guide and key to the orders provide a helpful starting point to begin the process of identification, followed by detailed identification keys in the introduction to each order of insects, which include many useful labelled diagrams and photographs.

At the end of the book is an assessment of Potential new orthopteroid species, a comprehensive Checklist, a list of Useful resources, and a Glossary of terms, followed by the detailed Distribution maps.

One of the many standout features of this guide is the beautiful artwork by Richard Lewington. With such a varied group of insects, how did you decide what to include in the illustrations?

Richard, as with all of the field guides that he has worked on, has done a spectacular job of illustrating this group of insects and the field guide contains more than 180 artworks. As a rule, adult males and females are illustrated for each species profile, unless they are all but indistinguishable e.g. American Cockroach, or parthenogenetic e.g. stick-insects and Surinam Cockroach.

Other significant colour forms (notably brown forms of otherwise green bush-crickets) have been included, and key features, such as the dorsal view of the head and pronotum of grasshoppers, and the cerci of earwigs, have been provided in colour. Key identification features also appear in the species profiles and illustrated keys as monochrome labelled diagrams.

This is the first book since Marshall & Haes’ 1988 Grasshoppers and Allied Insects of Great Britain and Ireland to cover all orthopteroid insects in Britain and Ireland. What’s changed for these insects in the 30+ intervening years?

In a relatively short period of time, we have moved from what was an essentially stable fauna, where new species were recorded as a result of more rigorous field work e.g. Heath Grasshopper, and taxonomic inspection e.g. Cepero’s Groundhopper, to a more dynamic situation where new species have, and are likely to continue to become, naturalised through climate induced migration e.g. Large Cone-head, and human-assisted introduction e.g. the Garden and Variable cockroaches. In all, ten new species have become successfully naturalised in Britain since the first species, the Southern Oak Bush-cricket, arrived in England in 2002, and three new species have been added to the Irish list, representing significant increases to the British and Irish fauna.

Another remarkable change, which had already shown signs of beginning when Marshall & Haes was published, has been the spectacular climate-linked spread of certain species (e.g. Roesel’s Bush-cricket, Long-winged Cone-head, Slender Groundhopper) across England, Wales, and for the Short-winged Cone-head, Scotland, and possibly Ireland. Conversely, there is tangible evidence to show that the Common Green Grasshopper, and possibly the Common Groundhopper, have experienced range contractions as drier conditions no longer cater for the hygrophilous requirements of their eggs.

There are many other points of interest. Many of the species that were introduced in imported food, such as the Cuban Cockroach, are no longer seen as biosecurity measures have improved, whereas the less regulated horticultural trade appears to continue to import alien species with worrying regularity, and has undoubtedly been the source of the recently naturalised Garden Cockroach and Variable Cockroach populations that are now well-established at sites across England. Improvements in pest control, together with more efficient heating systems, have also successfully eradicated once familiar species like the Oriental Cockroach, and of particular note has been the disappearance of the House-cricket, whose populations have additionally been lost through its susceptibility to the Cricket Paralysis Virus (CPV).

From your experience as the lead on the recording scheme for Orthoptera and allied insects, how has interest in these insects developed over the years and how do you hope the book will contribute in the future?

There is no doubt that the rise of the internet has played a major role in popularising the orthopteroid insects. It has facilitated the establishment of recording groups and allowed them to communicate rapidly with each other to share details of their finds, such as the important evidence of breeding for the Praying Mantis in the New Forest and the Isle of Wight this year. It also allows knowledgeable members of the group to rapidly confirm the identification of species. Record submission to the Recording Scheme is now easier, notably through iRecord, and the development of the mobile phone Grasshopper App means that species can be identified more easily in the field using illustrations of key identification features and song recordings.

In this context, the main contribution of this field guide is to provide information that will allow species that were previously not found in Britain and Ireland to be correctly identified. This is particularly the case for species like the two sickle-bearing bush-crickets and the newly naturalised cockroaches, for which there was previously very little information to work with.

As to role that this field guide will play in the future, as per the reasons provided in the Introduction, there is no better time to study the grasshoppers and allies. It is hoped that this comprehensive, technically useful, and aesthetically pleasing guide will inspire a new generation of enthusiasts to study this remarkable and often spectacular group of insects.

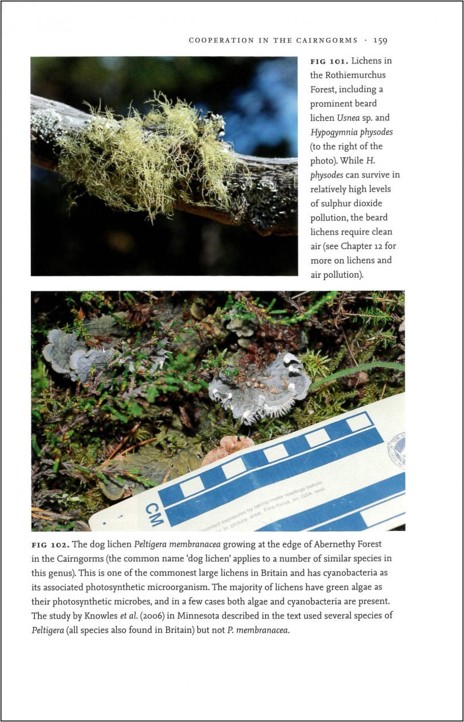

Silvertown (plant ecologist and science writer) was the member of the New Naturalist editorial board who oversaw my book. He liked the site based approach and encouraged me to use it throughout the book (his own popular book on plant diversity ‘Demons in Eden’ had used a similar approach). In many ways the approach grew out of my tendency to ‘tell stories’ when talking about ecology to beginning undergraduates. So in part the book is my lecturing style turned to prose.

Silvertown (plant ecologist and science writer) was the member of the New Naturalist editorial board who oversaw my book. He liked the site based approach and encouraged me to use it throughout the book (his own popular book on plant diversity ‘Demons in Eden’ had used a similar approach). In many ways the approach grew out of my tendency to ‘tell stories’ when talking about ecology to beginning undergraduates. So in part the book is my lecturing style turned to prose.

Because of the relatively early start of academic ecology in Britain the country has a number of very long running ecology field experiments. For example two I write about in the book are The Park Grass experiment at Rothamsted (started 1856) and the Godwin Plots at Wicken Fen (started 1927). Neither was started with the idea that they would run for 100 years or more – there is a large element of chance in their long-term survival. However, once an experiment has been running for a long time then people start to realise that such long runs of data are important and try and find the resources to continue them. More recent examples include (amongst many) the Buxton Climate Change Impacts Lab (which commenced in 1993 on limestone grassland in the Peak District) and grazing experiments set up in the Ainsdale Dunes system in Merseyside (started in 1974). But to be really long term requires luck and/or a succession of people determined enough to keep them going against the odds.

Because of the relatively early start of academic ecology in Britain the country has a number of very long running ecology field experiments. For example two I write about in the book are The Park Grass experiment at Rothamsted (started 1856) and the Godwin Plots at Wicken Fen (started 1927). Neither was started with the idea that they would run for 100 years or more – there is a large element of chance in their long-term survival. However, once an experiment has been running for a long time then people start to realise that such long runs of data are important and try and find the resources to continue them. More recent examples include (amongst many) the Buxton Climate Change Impacts Lab (which commenced in 1993 on limestone grassland in the Peak District) and grazing experiments set up in the Ainsdale Dunes system in Merseyside (started in 1974). But to be really long term requires luck and/or a succession of people determined enough to keep them going against the odds.

Over the coming months, British Wildlife will be exploring the many facets of rewilding as they relate to conservation in Britain through a new series, ‘Wilding for Conservation’, a title which, we hope, captures the wide range of approaches to letting nature take back control. We start things off in

Over the coming months, British Wildlife will be exploring the many facets of rewilding as they relate to conservation in Britain through a new series, ‘Wilding for Conservation’, a title which, we hope, captures the wide range of approaches to letting nature take back control. We start things off in