Turtles as Hopeful Monsters: Origins and Evolution

Turtles as Hopeful Monsters: Origins and Evolution

Written by Olivier Rieppel

Published in hardback by Indiana University Press in March 2017 in the Life of the Past series

Turtles have long vexed evolutionary biologists. In Turtles as Hopeful Monsters, Olivier Rieppel interweaves vignettes of his personal career with an overview of turtle shell evolution, and, foremost, an intellectual history of the discipline of evolutionary biology.

An initial, light chapter serves to both introduce the reader to important experts on reptile evolution during the last few centuries, as well as give an account of how the author got to study turtles himself. After this, the reading gets serious though, and I admit that I got a bit bogged down in the second chapter, which discusses the different historical schools of thought on where turtles are to be placed on the evolutionary tree. An important character here is skull morphology and a lot of terminology is used. Although it is introduced and explained, it makes for dense reading.

I think the book shines in the subsequent chapters that give a tour of the evolution of, well, evolutionary thinking.

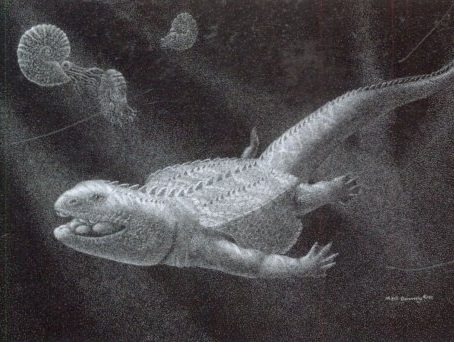

When Darwin formulated his theories, he argued that evolution is a slow and step-wise process, with natural selection acting on random variation to bring about gradual change. This is the transformationist paradigm.  The fossil record has yielded some remarkable examples where a slow transformation has occurred over time, such as the development of hooves in horses. But equally, there are many examples where no such continuous chain exists in the fossil record. Turtles are one such example, as they just suddenly appear in the fossil record, shell and all. Darwin himself attributed this to ‘the extreme imperfection of the fossil record‘. This lack of transitional fossils has of course been eagerly exploited by the creationist / intelligent design movement for their own ends.

The fossil record has yielded some remarkable examples where a slow transformation has occurred over time, such as the development of hooves in horses. But equally, there are many examples where no such continuous chain exists in the fossil record. Turtles are one such example, as they just suddenly appear in the fossil record, shell and all. Darwin himself attributed this to ‘the extreme imperfection of the fossil record‘. This lack of transitional fossils has of course been eagerly exploited by the creationist / intelligent design movement for their own ends.

But ever since Darwin, biologists have argued, and still do, that there exist mechanisms that allow for rapid innovation and saltatory evolution (i.e. evolution by leaps and bounds). This is the emergentist paradigm. Rieppel gives an overview of the different theories that have been put forward over the last two centuries, which is both illuminating and amusing. This covers such luminaries as Richard Goldschmidt (who coined the phrase “hopeful monsters”), Stephen Jay Gould (who revived it), and Günter Wagner (who provides the best current explanation according to Rieppel).

Just a little bit more about this phrase “hopeful monsters”, as this is such a prominent part of the book’s title. According to Goldschmidt, major new lineages would come about through mutations during early development of the embryo. This, of course, has the risk of producing monsters when the organism matures, likely resulting in premature death. So, Goldschmidt proposed a theory of hopeful monsters, where such drastic changes would successfully result in new evolutionary lineages with new body plans. His explanations, which required evolution to be goal-directed and cyclical (so-called orthogenetic evolution) have become obsolete, but he wasn’t entirely off the mark either. The best current explanations, according to Rieppel, comes from Wagner (author of Homology, Genes, and Evolution) and others who suggest radical changes to body plans do originate at the embryonic stage, and that the cause is the rewiring of the underlying genetic mechanisms.

The final two chapters of the book show how the debate over turtle shell evolution has gone back and forth between these two paradigms over time. Here again, Rieppel goes quite deep into morphology, this time of the shell, with accompanying terminology. Although the consensus seems to be leaning towards changes in embryonic development being responsible for the sudden appearance of the turtle shell in the fossil record, the final chapter deals with recent fossil finds from southwestern China that have revealed a potential missing link: a turtle with a fully developed belly shield.

The final two chapters of the book show how the debate over turtle shell evolution has gone back and forth between these two paradigms over time. Here again, Rieppel goes quite deep into morphology, this time of the shell, with accompanying terminology. Although the consensus seems to be leaning towards changes in embryonic development being responsible for the sudden appearance of the turtle shell in the fossil record, the final chapter deals with recent fossil finds from southwestern China that have revealed a potential missing link: a turtle with a fully developed belly shield.

Overall then, this book is a highly enjoyable romp through the intellectual history of evolutionary biology, using turtle evolution as its red thread. I could have used a bit more hand-holding here and there, and I feel the book would have benefited from an (illustrated) glossary or some extra illustrations. The reading gets quite technical when Rieppel goes into expositions on skull and shell morphology. That said, this book is an excellent addition to the popular science works in the Life of the Past series.

Turtles as Hopeful Monsters is available to order from NHBS.