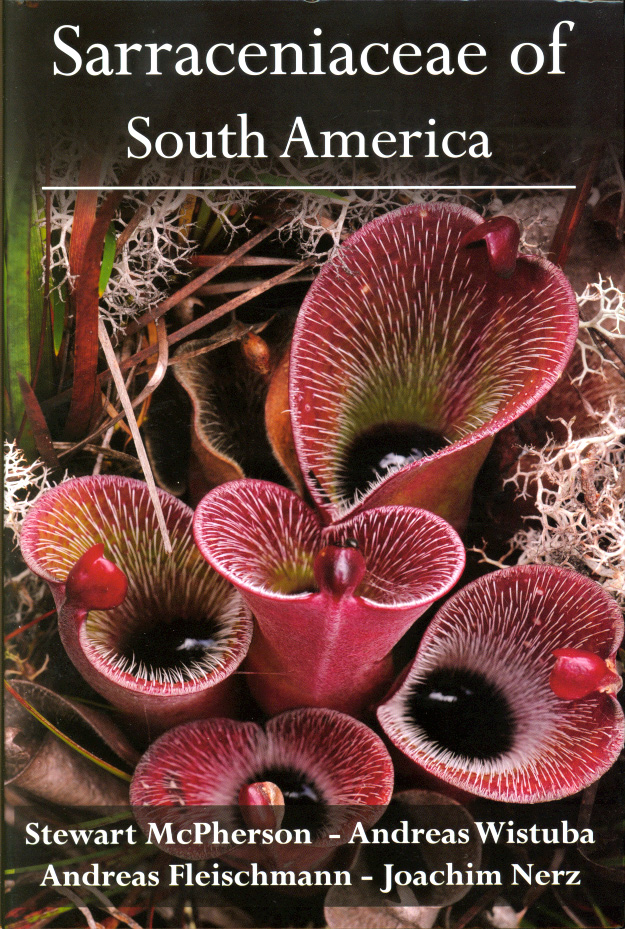

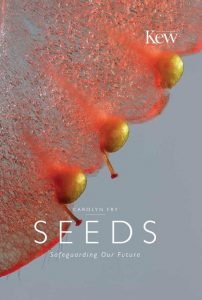

Seeds: Safeguarding Our Future

Seeds: Safeguarding Our Future

Written by Carolyn Fry

Published in hardback in April 2016 by Ivy Press

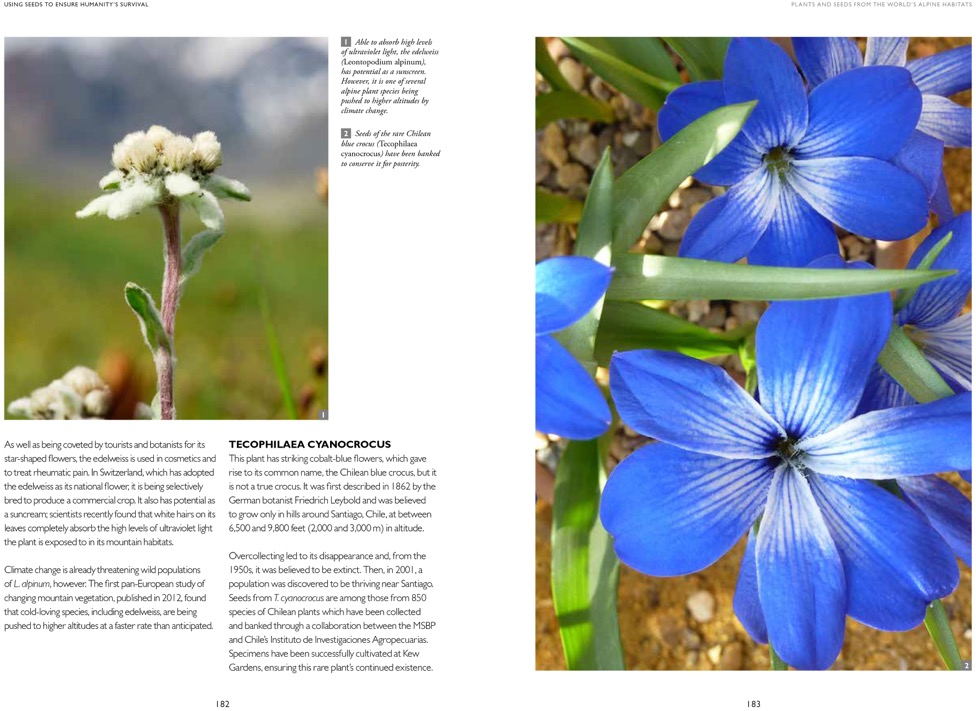

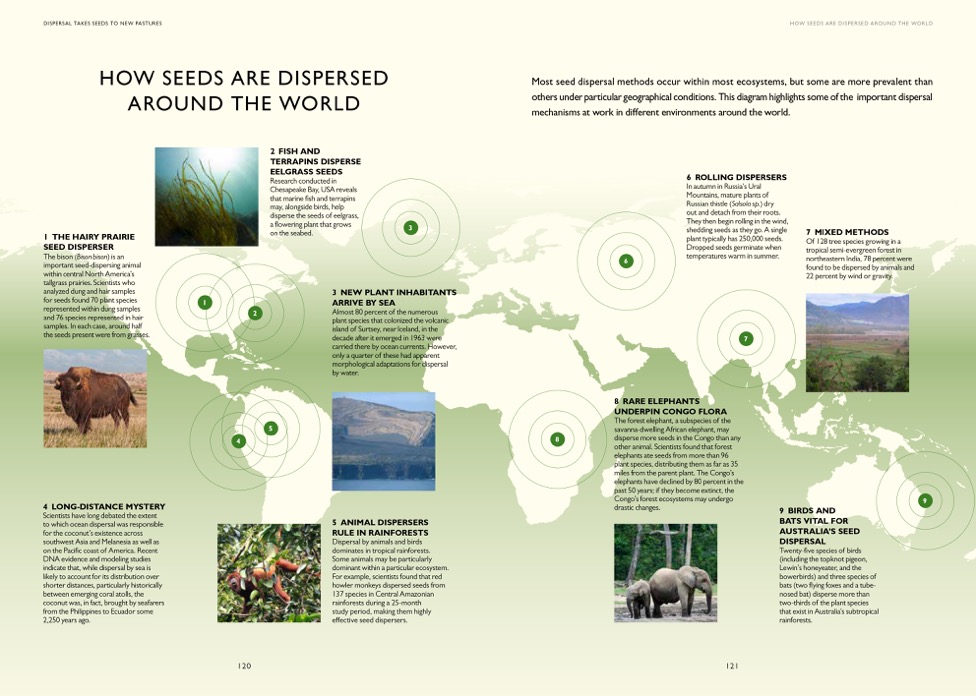

With a topic such as seeds and Ivy Press’s reputation for beautiful books you would be forgiven for thinking that this might be another coffee-table book in the same vein as the successful series of books published by Papadakis on seeds, pollen, and fruit. Although richly illustrated, Seeds: Safeguarding Our Future is very much a popular introduction to the biology of plants, focusing on seeds in particular, with pithy chapters covering evolution of plants, reproduction, seed dispersal, and germination. The subtitle gives away the angle this book takes though, with the first chapter on the importance of seeds to humanity, and the final chapter on how we might use seed biodiversity to ensure our own survival in the future. Though modern agriculture can feed many, its monoculture approach has also led to the loss of a large amount of genetic diversity. The dangers this could pose, especially with the impact of a changing climate, is a theme that runs throughout the book. Each chapter ends with a profile of a well-known plant and a profile of one of the many seed banks around the world that operate to conserve and catalogue the genetic diversity of plants.

Carolyn Fry is well-placed to write on this topic, having previously published books on Kew’s Millenium Seed Bank Project and on plant hunters. Furthermore, Kew Royal Botanic Gardens have endorsed the book and several of their experts have contributed expert advice. The book is a good primer on plant biology, and I noticed the short sections on, for example, reproduction were a great way to brush up on my slightly forgotten textbook knowledge. The seed bank profiles, pretty much one for each continent, are interesting little sections, highlighting the important work done here to safeguard against future threats to agricultural crops. Though shortly mentioned in the final chapter, I would have loved to have seen the futuristic Svalbard Global Seed Vault profiled in the same way. As a planetary back-up of agricultural seed collections around the world, this surely is one of the most impressive and intriguing seed banks.

All in all this is an excellent introduction to seed biology with a focus on conservation and agricultural importance, executed to Ivy Press’s typical high production standards.

Seeds: Safeguarding Our Future is available to order from NHBS.