The Orchid Outlaw tells the tale of author Ben Jacob’s mission to save some of the UK’s rarest, native orchids. With many facing extinction due to land use change and the climate crisis, while also not being protected by environmental and planning laws, Ben took it upon himself to rescue these threatened plants and grow them in his own kitchen and garden, rather than losing the plants all together. In doing so, he placed himself on the wrong side of the law. This part memoir, part natural history piece shows us how we can all save the world one plant at a time.

The Orchid Outlaw tells the tale of author Ben Jacob’s mission to save some of the UK’s rarest, native orchids. With many facing extinction due to land use change and the climate crisis, while also not being protected by environmental and planning laws, Ben took it upon himself to rescue these threatened plants and grow them in his own kitchen and garden, rather than losing the plants all together. In doing so, he placed himself on the wrong side of the law. This part memoir, part natural history piece shows us how we can all save the world one plant at a time.

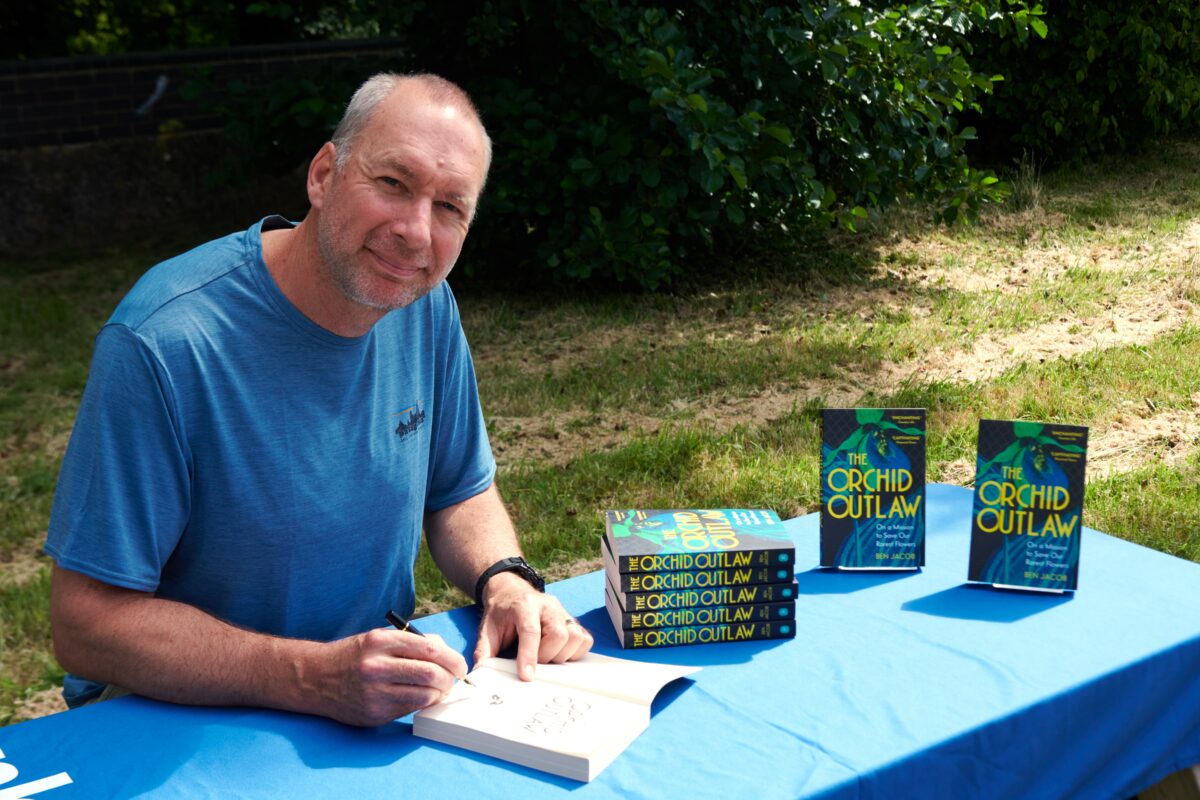

Ben works as a University lecturer by day, and as a clandestine ecologist, conservationist and Orchid-saviour by night. It is always a pleasure to meet the authors behind our books, particularly those who are adopting their own approach to nature restoration and conservation, and we were delighted to have the opportunity to talk to Ben in person about The Orchid Outlaw and have him sign our books. We discussed how he first became interested in Botany, his thoughts on the Right to Roam movement, what he hopes the reader can learn from his book and more. Read the full author interview on the Conservation Hub.

Ben works as a University lecturer by day, and as a clandestine ecologist, conservationist and Orchid-saviour by night. It is always a pleasure to meet the authors behind our books, particularly those who are adopting their own approach to nature restoration and conservation, and we were delighted to have the opportunity to talk to Ben in person about The Orchid Outlaw and have him sign our books. We discussed how he first became interested in Botany, his thoughts on the Right to Roam movement, what he hopes the reader can learn from his book and more. Read the full author interview on the Conservation Hub.

Firstly, can you tell us about yourself and how you first became interested in both Botany and orchids?

By day I’m a mild-mannered lecturer (in a subject which has very little to do with science or botany); by night I am a guerrilla conservationist with a focus on rescuing, conserving, and bringing back to the land, our native orchids. The Orchid Outlaw explains the journey I took from a chance encounter with a tropical orchid in a garden centre as a child, which led me, when I was older, to trekking through jungles to look for tropical species, then, and older still, via a mugging, an enforced return to England and a broken back, to encounter Britain’s – and Europe’s – native orchids. As I learned more about these species, I realised that my preconceptions about our native orchids and the state of our natural environment were wrong. I became aware of the significant recent decline in orchid populations… and began my unorthodox means of saving them. I tell this story alongside (hopefully) entertaining diversions through history, medicine, man’s changing relationship with nature, Charles Darwin’s discovery of evolution, and a critical exploration of the laws which exist to protect wildlife in this country – but which are so full of huge holes that battalions of construction vehicles can rumble straight through, crushing all life before them. Which they do. Daily. Without any legal consequences.

In contrast, a well-intentioned conservationist (like me) rescuing wild flora or fauna from private land which is about to be turned into a housing estate, without first going through the hurdles required to gain permission from the landowner, risks fines of £5,000 per plant or six months in prison. Do these laws make sense? No. Are they helping sustain a healthy and diverse population of native species? No. So, like any laws which don’t work, someone should stand up to them and do what needs to be done.

In the past week, the European Council has formally adopted the Nature Restoration law. Do you think this law could have any influence on conservation policy here in Britain, and to what extent do you think it will change people’s attitudes towards our responsibility to protect the natural environment?

In Britain (as elsewhere) 2024 is a national election year so any impact on British political attitudes of a European law will depend to an extent on which party wins. Unfortunately, none of our main political parties have a good track record when it comes to protecting our natural heritage for us and future generations – we have seen a rapid decline in numbers across all species and native habitats over many decades presided over by both main parties and a coalition. Of course, for the sake of everyone’s future, I’d like to think this European Council law marks a shift in geo-political will which will pull all national policies into its orbit (fingers-crossed)… but the realist in me suggests that unless meaningful, accountable, well-policed penalties accompany laws, those laws tend to make little concrete difference (consider for example international laws around freedom of expression, asylum, and war crimes, which are broken all around the world every day).

The Orchid Outlaw highlighted how pre-industry anthropogenic land use is intertwined with orchid distribution, particularly in the UK. How do you think rewilding (which is currently a very hot topic) can be implemented in a way that supports these species that may have benefitted from traditional land management rather than being left to nature?

The Orchid Outlaw looks a little bit at how native orchids thrived in the habitat niches created on a large scale by man, including hay meadows, and how centuries of people-managed woodland (the clearing of underwood and occasional felling) provided conditions which helped many native orchid species to thrive. Of course, these habitats had existed long before people (meadows had been formed, for example, by large, now extinct cattle, naturally falling trees, and wildfires) so, in many ways, mankind took on the role of these natural forces for his own benefit and, in the process, allowed many other species – not only orchids – to benefit too. In this sense, ‘rewilding’ is not simply a case of letting an area go wild without any human intervention – ironically this kind of habitat is completely ‘un-wild’ unless it is stocked with the right range of creatures which are going to complete the tapestry of life (and death) needed to reach a healthy, natural, sustainable equilibrium.

How can we mitigate orchid loss in a practical conservation framework when vital species-specific symbiotic relationships with fungi are not considered, so these species may not be protected under current schemes?

There are all kinds of gaping holes in our awareness of the world – and what really goes on in the soil, which sustains everything, is one of them. Because of this particular hole, soil health has fallen through the gaps of wildlife conservation laws, even though soil, like the sea, is a vast, living, environment containing more life than we can see and it is an environment upon which the world depends. Orchids in particular have a very complex, as yet only partially understood, crucial relationship with certain soil fungi (mycorrhizae). This is because orchid seed germinates unlike that of any other plant. It creates a symbiotic relationship with a specific mycorrhiza in order to then form a kind of hairy blob (a ‘protocorm’) which, eventually, sometimes after many years living underground sustained only by fungus, becomes a flowering plant. This makes orchids important indicators of soil health, because it seems that the mycorrhizae they need are adversely affected by artificial fertilisers and herbicides. In a way then, our orchids have taught me that any conservation framework has to start from the ground – literally, the dirt – up, because that is the secret to success. If the earth and the microbes in it are right for the plants there – and, of course, plants are crucial to any rewilding project – then insects, birds, mammals will come and the tapestry of life which orchids introduced to me will weave itself.

The right to roam movement is growing, especially close to home here in Devon. What are your thoughts on trespassing for the purpose of immersing and enjoying nature that is legally out of reach for the majority of citizens? Following this, if the laws were to change do you think it would affect attitudes towards nature with more people having the chance to be exposed to nature?

Let’s be honest, this is ‘our’ land. Our ancestors built it, fought for it, died for it, are buried in it; it is deplorable that we do not have the right to roam – considerately and with respect – upon our land. The right to roam exists in Scotland without any major detriment to anybody and the fact that it does not exist in England and Wales says a great deal about the sway the old class system still holds here – after all, 0.06% of the population owns half of rural England and Wales and much of this land distribution extends back to the days of feudal lords. For centuries, no one has done much to change this status quo.

Obviously, allowing people the chance to experience nature is a great way of changing attitudes to it… but a lot of the land we can roam in Devon is still unavailable to those in inner city areas, so a shift in awareness towards our natural world – our natural heritage, formed over thousands of years and which we should be proud to pass on to our children –– is not solely about opening up rural land. The recent pandemic made many people far more aware of how important being outside in nature is to our wellbeing – whether in a park or allotment or an uncut verge with a bench to sit on and wild flowers buzzing with insects and flickering with butterflies. So, while the right to roam is important, I think wider appreciation of the real value of nature will be helped by allowing nature to be more present everywhere in everyone’s life – from green roofs, wild parks and county farms, to unmown verges and tree-lined streets smothered in bird boxes…

What do you hope the reader can learn from The Orchid Outlaw?

On the one hand, I like to think that The Orchid Outlaw takes a reader on the same journey of discovery I went on, with orchids as my guide, opening my eyes to so much I hadn’t known. One of the biggest wake-up calls orchids gave me was the inadequacy of our wildlife laws and the massive, underreported decline of some our native flora. Orchids also taught me about the important microfauna all around us, the complex nature of soil, the history of botany and herbalism, and of course the fascinating world of native orchids themselves – the magical co-evolution that has occurred between orchids and their pollinators, the fact that some species never need sunlight, that others grow a metre tall and smell of decay, and some can live to be over a hundred years old… and a great deal more.

On the other hand, and perhaps more importantly, I’d like to think that what I do, as unorthodox as it is, shows that you don’t have to be a scientist, researcher, or working for an official institution to make a positive impact for the other living organisms on our planet.

Can you tell us what’s occupying your time at the moment? Do you have any other books in progress that we can hear about?

Aside from the usual rescuing and reintroducing native orchids, at the end of The Orchid Outlaw I talk about moving to the countryside to an old house which needed – and continues to need – a lot of attention. So, the garden (which was essentially a forest of nettles) and the lab I started building at the bottom of the garden to propagate orchids (so I no longer need to turn the kitchen into my lab) is largely what occupies my spare time. In any spare moments I am working on a couple of book proposals, both of which relate to elements of The Orchid Outlaw, but, for now, they’re closely guarded secrets!

The Orchid Outlaw has been published by John Murray and is available from our online bookstore.

Joe Shute is an author and journalist who has a keen passion for the natural world

Joe Shute is an author and journalist who has a keen passion for the natural world

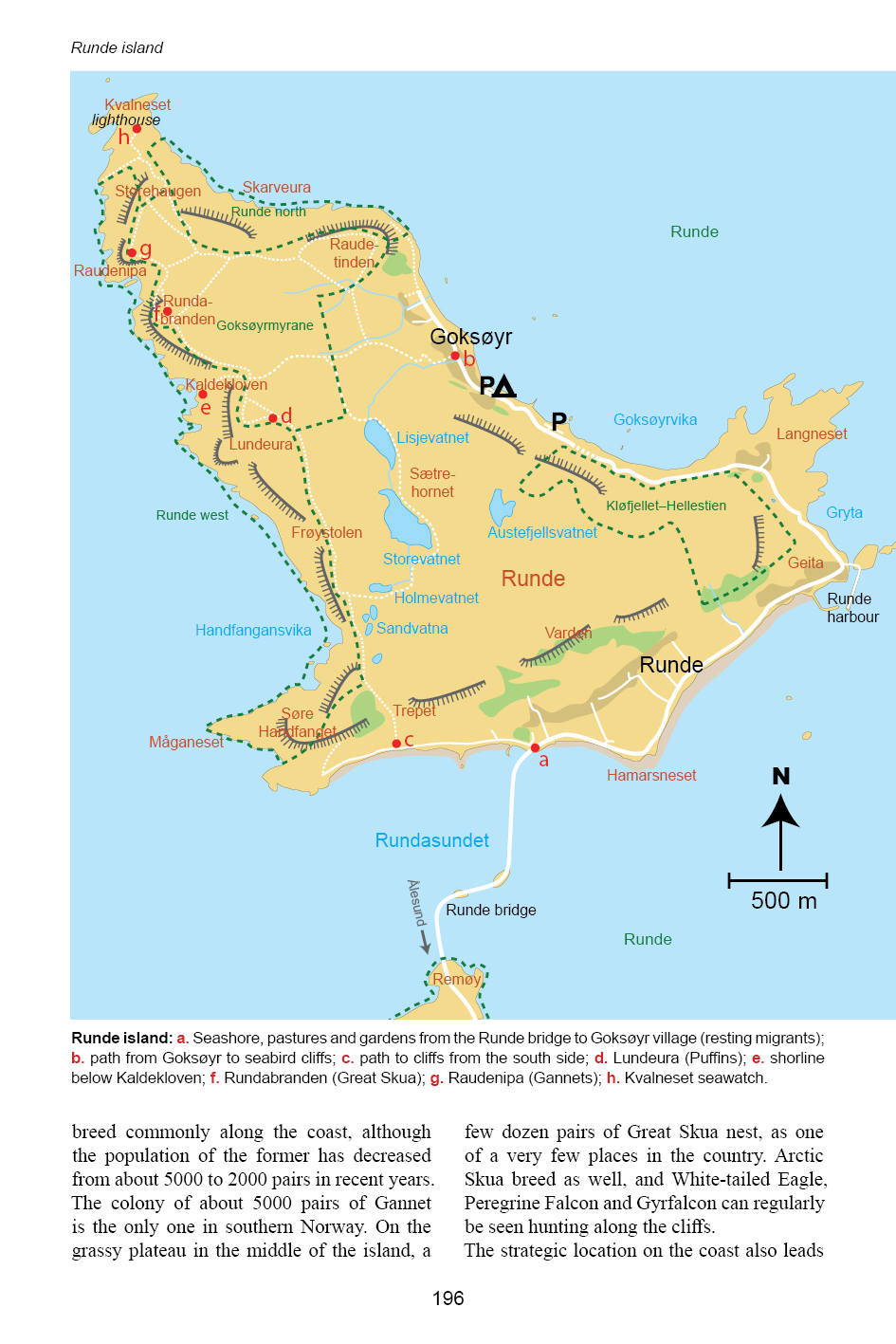

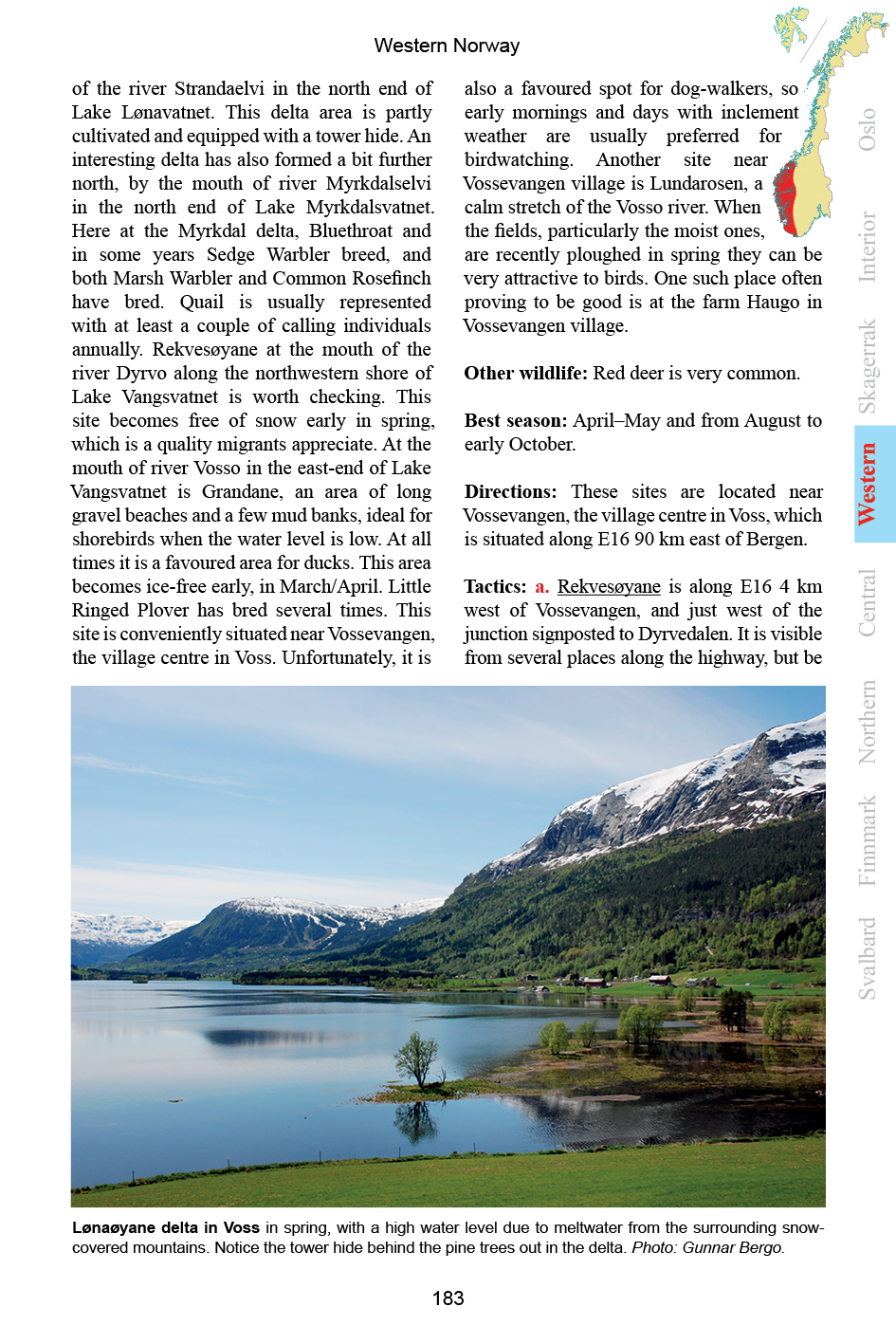

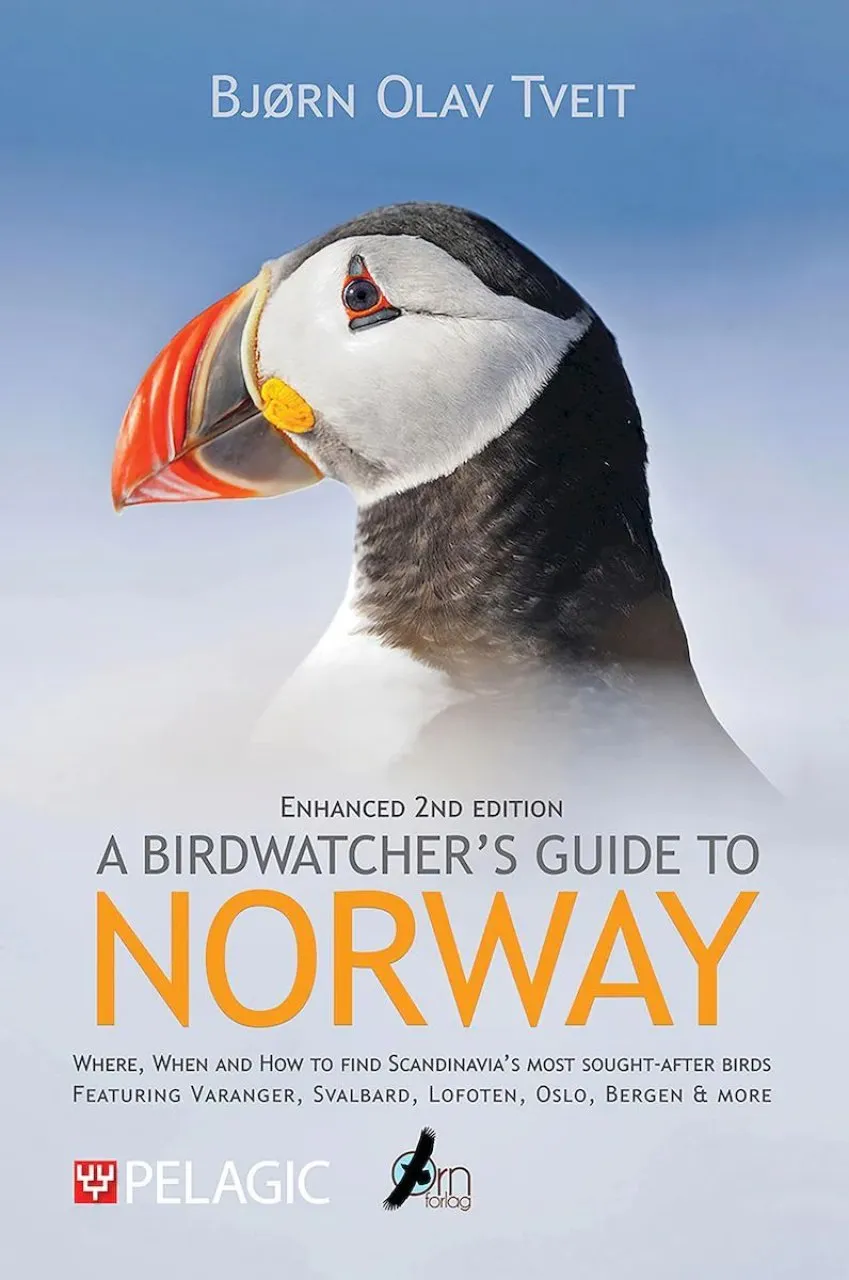

Bjørn Olav Tveit lives in Oslo, Norway and has explored many of the country’s best birding sites throughout his life. He is a long-standing member of the Norwegian Rarity Committee for Birds and acts as the nature conservation contact for his local BirdLife Norway division. He runs bird-spotting guided tours for nature enthusiasts, composes music, authors books and works for the Norwegian Ministry of Culture.

Bjørn Olav Tveit lives in Oslo, Norway and has explored many of the country’s best birding sites throughout his life. He is a long-standing member of the Norwegian Rarity Committee for Birds and acts as the nature conservation contact for his local BirdLife Norway division. He runs bird-spotting guided tours for nature enthusiasts, composes music, authors books and works for the Norwegian Ministry of Culture. Firstly, can you tell us a little about yourself and how you got into birdwatching?

Firstly, can you tell us a little about yourself and how you got into birdwatching?