The Mar Lodge Estate in the heart of the Cairngorms was acquired by the National Trust for Scotland in 1995, and has since experienced landscape-scale restoration with outstanding results. Discussing conservation, rewilding and land management, Regeneration is an honest account of both the progress made at Mar Lodge Estate and the challenges faced over the last 25 years.

After studying Environmental Anthropology at Aberdeen University, Regeneration author Andrew Painting moved to Scotland to volunteer with the RSPB. Since 2016, he has been Assistant Ecologist at the Mar Lodge Estate, and has documented its slow recovery. He has very kindly agreed to answer some questions about his book.

Could you tell us a little about your background and where the motivation for this book came from?

I’m a lifelong naturalist, but it took me quite a while to take the plunge into working professionally in conservation. My first degree was in English Literature, so I’m glad I’ve finally been able to put it to good use! I’ve been working in the ecology team at Mar Lodge since 2016, when the fruits of two decades of hard work were beginning to show, and I instantly fell in love with the place. By 2018, all the graphs and reports we were producing were looking very respectable, and I realised we were sitting on a story that deserved a larger audience than it was getting at the time. 2020 was the 25th anniversary of the National Trust for Scotland acquiring the site, and one eighth of the way into the Trusts’ 200 year management vision for the land, so it seemed like a good time for a stock-take.

Of course, it’s never as simple as that. Mar Lodge Estate is not perfect (nowhere is), and as I got down to writing the book I realised that the social and political complexities of the ‘Mar Lodge experience’ were just as important to discuss as the successes.

Though far more is needed to keep up with the increasing levels of environmental destruction, you write of much hope for the future. What do you think is the current biggest challenge conservationists are up against?

Often, the biggest challenge to solving any problem is getting people to accept that there is a problem in the first place. Thanks to decades of campaigning from people from all walks of life, I think we are now at the point where there is broad agreement about the scale of the twinned environmental and climate crises, and the necessity of social change to address them. Politicians across the political spectrum are waking up to the fact that environmental conservation is both a vote-winner and also extremely good value for money, while the private sector is realising that nature-based businesses can be both highly profitable and enjoy high levels of public support.

So now I think that the challenge is to be bold and ambitious, and to make the most of this ‘unfrozen moment’. We need nature, not just in our National Nature Reserves and SSSIs, but also in our farms and seas, along roadsides, in our urban areas, schools and places of business. We now need to lobby those increasingly receptive politicians to instigate progressive policies that incentivise returning nature to these places. To that end, for me, the real power of Mar Lodge Estate is not in the amount of wildlife or carbon it holds, but in the example of ecological restoration that it sets to other Highland estates.

Could you talk about a particular conservation success story over the course of the project?

With any luck, in the years to come the landscape-scale restoration of high altitude woodland across the Cairngorms will become a ‘textbook example’ of an effective, large-scale and long-term conservation project. This habitat, a mixture of cold and wind-stunted birch, juniper, pine and montane willow species, has been almost lost from the UK. But we are beginning to see it return at a landscape level at Mar Lodge and much more widely across the Cairngorms and Scotland. In the Cairngorms, this has been facilitated by a really nice mixture of traditional conservation work, high-tech genetics work and landscape-scale partnership working. This is still very much work-in-progress, but what’s really exciting about it for me personally is that we’re really only at the very beginning of a journey which will play out over decades. So every time I head out into the high hills I’m excited to see what I will come across.

Has documenting this project inspired you to get involved in any other long-term initiatives?

There’s a lot to choose from these days! I’m originally from the West Country, so have fond memories of the Avalon Marshes and Steart – both of which are hugely exciting projects. I’ll never forget seeing and hearing my first cranes on a very cold winter day in the Somerset Levels. But for sheer size and ambition, there are few projects more exciting than the ones currently underway in the Cairngorms.

You talk about the well-documented value of nature for our mental health, while also questioning how to facilitate the means for people to enjoy and benefit from nature without harming it in the process. Do you think eco-tourism is beneficial to conservation?

It certainly can be! There are projects across Scotland which are highlighting the benefits of eco-tourism to local economies, from the Borders to Mull to Cromarty to Sutherland. But eco-tourism isn’t a silver bullet – areas which are dependent on a single industry or land use are incredibly vulnerable to social, economic and ecological change, so it should really be seen as part of a larger solution to environmental problems, rather than a solution in and of itself. I do feel that potential impacts of eco-tourism on sensitive habitats and species can generally be mitigated through good land management practices, better education and more awareness of our own personal responsibilities towards nature. And of course, for nature to really thrive, we need to remember how to live alongside it everywhere. Why should people be content to see charismatic wildlife only on their holidays?

This is your first book, and it is a great achievement. Do you think it will be the first of many?

Right now I’m just looking forward to getting back out into the field! I’m not sure about ‘many’, but I think I’ve got a couple more books in me. And of course, I’ll have to do another Mar Lodge book in 25 years’ time to check in on progress!

Regeneration: The Rescue of a Wild Land

Regeneration: The Rescue of a Wild Land

By: Andrew Painting

Hardback | March 2021 | £16.99 £19.99

“Deftly weaving through the social and political complexities of nature conservation in Scotland the Regeneration of Mar Lodge is testimony to the miracles that can happen when disparate interests come together in common cause.”

Isabella Tree, author of Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm.

Browse our selection of conservation and biodiversity books

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

Heathlands defy ready definition. The diverse places that we call heaths are cultural landscapes which are overlain with the language of ecology. It is unnecessary to reconcile these different perspectives as both traditions offer a path to understanding what makes our heathlands special.

Heathlands defy ready definition. The diverse places that we call heaths are cultural landscapes which are overlain with the language of ecology. It is unnecessary to reconcile these different perspectives as both traditions offer a path to understanding what makes our heathlands special. It is not inevitable that the catastrophic losses of the recent past are the destiny of our remaining heaths. Whilst there are still significant challenges to overcome, we know enough about these habitats to secure their place in the countryside of the future, as an integral part of British culture and home to a wealth of species that occupy ecosystems of immense richness.

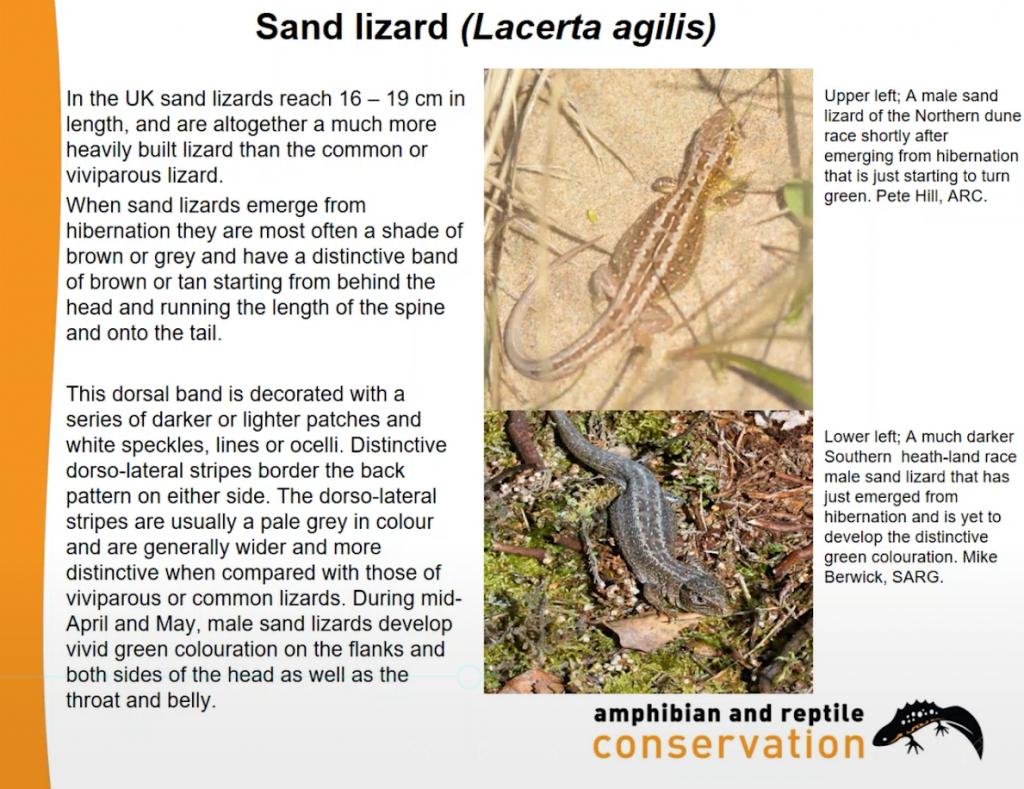

It is not inevitable that the catastrophic losses of the recent past are the destiny of our remaining heaths. Whilst there are still significant challenges to overcome, we know enough about these habitats to secure their place in the countryside of the future, as an integral part of British culture and home to a wealth of species that occupy ecosystems of immense richness. Heathlands are a great deal more than just carpets of heathers. A heathland landscape can embrace habitats as diverse as rocks and lakes and bogs, even temporary stands of arable and wartime concrete. The component habitats of a large functioning heathland are naturally dynamic, with species dependant on all sorts of habitat formations, from bare ground to the decaying of cowpats. The great antiquity of heathland ecosystems is reflected in the network of interdependent species, many of which are associated with large herbivores, fire and occasional gross disturbance of the soil. Whilst charismatic birds and reptiles have traditionally claimed the limelight, the biological wealth of the heath is better expressed through its invertebrates, lichen and wildflowers.

Heathlands are a great deal more than just carpets of heathers. A heathland landscape can embrace habitats as diverse as rocks and lakes and bogs, even temporary stands of arable and wartime concrete. The component habitats of a large functioning heathland are naturally dynamic, with species dependant on all sorts of habitat formations, from bare ground to the decaying of cowpats. The great antiquity of heathland ecosystems is reflected in the network of interdependent species, many of which are associated with large herbivores, fire and occasional gross disturbance of the soil. Whilst charismatic birds and reptiles have traditionally claimed the limelight, the biological wealth of the heath is better expressed through its invertebrates, lichen and wildflowers.

Professor Jeff Ollerton is a researcher, educator, consultant and author, specialising in mutualistic ecological relationships – in particular, those between plants and their pollinators. Now one of the world’s leading experts on pollinators and pollination, he has conducted field research in the UK, Australia, Africa, and Tenerife, and published a huge body of ground-breaking research which is highly-cited and used at both national and international levels to inform conservation efforts. Jeff currently holds Visiting Professor positions at the University of Northampton in the UK and Kunming Institute of Botany in China.

Professor Jeff Ollerton is a researcher, educator, consultant and author, specialising in mutualistic ecological relationships – in particular, those between plants and their pollinators. Now one of the world’s leading experts on pollinators and pollination, he has conducted field research in the UK, Australia, Africa, and Tenerife, and published a huge body of ground-breaking research which is highly-cited and used at both national and international levels to inform conservation efforts. Jeff currently holds Visiting Professor positions at the University of Northampton in the UK and Kunming Institute of Botany in China.

While professional scientific research, alongside informed policy change, will obviously be key in directing the future of pollinators around the world, you also mention the importance of amateur naturalists and citizen scientists in collecting data and providing some of the legwork behind sustained long-term studies. What advice would you give to a non-professional individual who wishes to get involved with pollinator conservation? (eg. volunteering, donating to charities/organisations, lobbying for policy change etc.)

While professional scientific research, alongside informed policy change, will obviously be key in directing the future of pollinators around the world, you also mention the importance of amateur naturalists and citizen scientists in collecting data and providing some of the legwork behind sustained long-term studies. What advice would you give to a non-professional individual who wishes to get involved with pollinator conservation? (eg. volunteering, donating to charities/organisations, lobbying for policy change etc.) I discovered lots of interesting things from your book that I previously didn’t know – such as the fact that there are pollinating lizards! In all of your years of study, what is the most fascinating fact that you have learned about pollinators?

I discovered lots of interesting things from your book that I previously didn’t know – such as the fact that there are pollinating lizards! In all of your years of study, what is the most fascinating fact that you have learned about pollinators? Finally, what are you working on currently, and do you have plans for further books?

Finally, what are you working on currently, and do you have plans for further books?

You point out that the majority of published behavioural observations have been of mature females. What do we know about males and immature spiders? Is web construction specifically a female activity? Or have we just not looked hard enough?

You point out that the majority of published behavioural observations have been of mature females. What do we know about males and immature spiders? Is web construction specifically a female activity? Or have we just not looked hard enough? You mention that orb webs are neither the pinnacle of web evolution nor necessarily the optimally designed structures that they are often claimed to be. Most organismal traits are a product of history and contingency as much as natural and sexual selection. I might be asking you to speculate here, but, in your opinion, are there any particular evolutionary thresholds that spiders have not been able to cross that would make a big difference for web construction?

You mention that orb webs are neither the pinnacle of web evolution nor necessarily the optimally designed structures that they are often claimed to be. Most organismal traits are a product of history and contingency as much as natural and sexual selection. I might be asking you to speculate here, but, in your opinion, are there any particular evolutionary thresholds that spiders have not been able to cross that would make a big difference for web construction? Producing a book of this scope must have been a tremendous job, and you remark that a thorough, book-length review of spider webs had yet to be written, despite more than a century of research on spiders. With the benefit of hindsight, would you embark on such an undertaking again?

Producing a book of this scope must have been a tremendous job, and you remark that a thorough, book-length review of spider webs had yet to be written, despite more than a century of research on spiders. With the benefit of hindsight, would you embark on such an undertaking again?