To the casual observer, global summits and the resolutions they produce can seem frustratingly ineffective – repeating cycles of targets set, missed and reset, with no obvious progress. Yet despite the apparent inertia, when used to good effect these processes can be powerful tools for positive change. International Treaties in Nature Conservation: A UK Perspective provides a unique insight into the inner mechanisms of international treaties – their history, development, successes and failures – from those who have spent their lives working with them.

To the casual observer, global summits and the resolutions they produce can seem frustratingly ineffective – repeating cycles of targets set, missed and reset, with no obvious progress. Yet despite the apparent inertia, when used to good effect these processes can be powerful tools for positive change. International Treaties in Nature Conservation: A UK Perspective provides a unique insight into the inner mechanisms of international treaties – their history, development, successes and failures – from those who have spent their lives working with them.

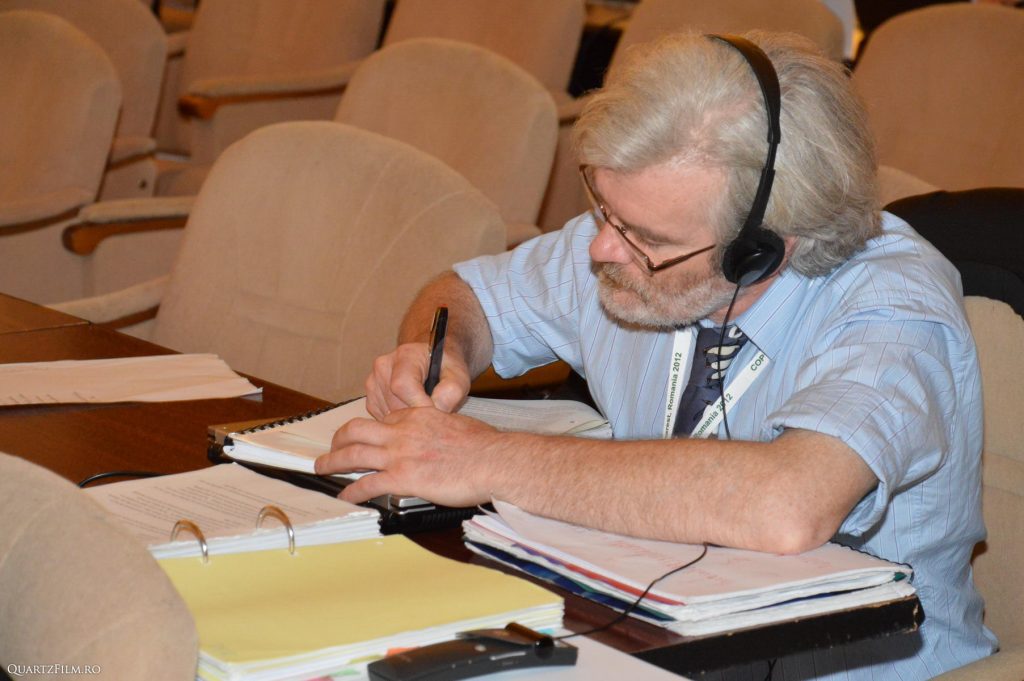

All of the authors involved in this book bring a huge wealth of expertise from their past and current positions within both statutory and non-government nature conservation organisations and academia. One of the authors, David Stroud, kindly agreed to answer a few of our questions.

International treaties are directly responsible for some of the greatest environmental success stories in modern history. But despite their importance, their role in nature conservation is not one many of us are familiar with. How important do you think it is that the mechanisms of these treaties are more widely understood?

It’s hugely important. Not only do these treaties establish some of the most important conservation objectives, but they provide a means of learning from other experience. Typically, international treaties set a broad goal – such as ‘the wise use of wetlands’ in the case of the Ramsar Convention – but are much less prescriptive as to exactly how this will be delivered nationally. Accordingly, there is much to learn from the broad diversity of other national conservation experience in implementing treaty obligations. Such comparative experiences make these treaties fascinating and their study valuable.

It’s hugely important. Not only do these treaties establish some of the most important conservation objectives, but they provide a means of learning from other experience. Typically, international treaties set a broad goal – such as ‘the wise use of wetlands’ in the case of the Ramsar Convention – but are much less prescriptive as to exactly how this will be delivered nationally. Accordingly, there is much to learn from the broad diversity of other national conservation experience in implementing treaty obligations. Such comparative experiences make these treaties fascinating and their study valuable.

They also provide important drivers of national conservation policy. Thus, for example, it was the obligation under the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement to phase out the use of lead gunshot in wetlands by 2000 that created the policy incentive resulting in legislation across the UK to that effect from 1999.

There has been a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the departure of the UK from the European Union, and what this means for conservation. In terms of environmental protection and influence during the development of international treaties, what are the implications of leaving the EU?

Lots of issues here! As we explain, there are also serious risks to standards of environmental protection, especially the removal of strong compliance mechanisms that hold government to the environmental obligations it has assumed, and for which proposed domestic replacements look far from sufficient and have yet to be introduced. That said, some aspects of EU policy, most notably the Common Agricultural Policy, have driven significant harm to nature and to natural systems, and here the promise (as yet unrealised) of a new domestic approach which confines the payment of public money to the delivery of public goods, could mark a significant improvement in the state of nature in the farmed environment.

But there is also a risk that there may be an appetite to replace well-established processes and priorities, developed in partnership with EU states, with unique UK approaches, without reference to their efficacy. Whilst there is always room for improvement, including of existing EU processes, it is important that any such improvements build on existing systems and lessons learnt, and avoid causing delays and disruption that would take time we do not have, given the urgency of the environmental challenges we face.

Many aspects of environmental protection are inherently international in nature, with neither species, habitats nor many of the factors which drive their decline respecting national boundaries. As such there is a clear and ongoing imperative for international cooperation and alignment. The UK, outside of the EU, could take this opportunity to drive up ambition, but risks having less influence on environmental policy development, and becoming increasingly remote from wider thinking and ideas both within the EU and beyond, unless UK governments take pro-active steps to rebuild lines of communication and forums for engagement.

Chapter 8 ‘The impact of UK actions on an international scale’ goes into detail about the UK’s contributions to nature conservation beyond its borders, whether these be, for example, monetary, scientific research, or the role of UK non-governmental organisations (NGOs). In your opinion, do you think the UK is doing enough?

The UK is doing a lot, but by no means enough. Formal financial inputs to international treaties (which we estimate as £2,001,000 in 2019/20) are frankly trivial compared to either the size of the UK government budget in the same year (£842,000,000,000) or indeed the immensity of the issues to be addressed. Whilst both climate change and biodiversity loss have been recognised as ‘crises’ or ‘emergencies’, yet to date, it is hard to see responses from the UK, let alone the wider international community reflecting this, or being much more than complacent ‘business as usual’. And these will have no realistic chance of success.

Following on from the previous question, this book highlights the role and importance of NGOs (and a number of the authors themselves have been or are currently involved with NGOs). Do you think NGOs should have more involvement in environmental policy, both within the UK and on a global scale?

Following on from the previous question, this book highlights the role and importance of NGOs (and a number of the authors themselves have been or are currently involved with NGOs). Do you think NGOs should have more involvement in environmental policy, both within the UK and on a global scale?

NGOs have a critical role to play in international conservation, both representing ‘civil society’ and also – in many cases – holding considerable technical expertise and knowledge, essential to the effective conservation delivery. Yet the dynamic of relations with governments is interesting! NGOs are not uninterested parties being driven by their own organisational priorities, responsive to their memberships, and typically having developed country perspectives. Their interests can sometimes be limited to a single species (witness the many NGOs concerned with charismatic megafauna such as lions and elephants). In contrast, and especially in democracies, governments have wider responsibilities such as the need to maintain economies, create infrastructure, or alleviate poverty.

The role of NGOs in pushing governments to deliver strong outcomes for the environment is critical and they have a key role, working with government, in practical implementation ‘on the ground’. In the UK, there are typically good relationships between government and NGOs, yet we outline considerable scope for improvement. However, within the UK governments, there can be an attitude that sees environmental NGOs as the problem rather than an essential part of the solution. Which is unnecessary and regrettable.

This book delves into the history of international instruments (such as Agreements, Conventions and legislation), and it is pointed out that fewer new treaties have been made since the early 2000s. Why do you think this is the case?

There are probably two issues at work here. An international landscape of ever proliferating treaties may not be particularly efficient means of engaging the attention of governments. Indeed, one would hope that at some point we see treaties retired following fulfilment of their objectives. Unfortunately, the state of the world is such that we seem far from this eventuality.

It is possible that we already have treaties covering all the relevant issues. However, whilst the ‘big stuff’ (climate change, migratory species, wetlands, trading endangered species) is indeed covered, there are certainly other ‘gaps’ – for example effective regulatory systems for sustainable harvesting of marine resources (to replace the very many completely ineffective fisheries treaties).

Additionally there seems to be an ever-growing culture of legal risk aversion within governments. This, and a retreat to more nationalistic political outlooks in many countries, is not supportive of new treaty-building.

In November, the UK will host the next UN climate change conference COP26 in Glasgow. What do you envisage, or hope, will be the outcome of the conference?

In November, the UK will host the next UN climate change conference COP26 in Glasgow. What do you envisage, or hope, will be the outcome of the conference?

Hoping and envisaging are two very different things! I’ll stick to hoping for now…

It’s human nature to defer difficult decisions: why do today what one can put off till tomorrow? This is especially the case for governments faced with decisions that have difficult political consequences. Essentially the challenge at COP 26 will be to deliver on the aspiration agreed in Paris to hold the global temperature increase to less than 1.5 oC above pre-industrial levels. Unlike the quota-based approach of the earlier Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement aims to build to necessary levels of global emissions reductions from bottom-up – through collective ‘Nationally Determined Contributions’ (NDC). After years of deferral of the difficult issue of how to do this, now is finally the time to deliver. Already, there is much diplomatic peer pressure – led especially by UK and USA – to encourage ambitious NDCs. But whether we get to levels that will deliver the Paris Agreement objective remains to be seen. It’s critical that we do as time is running out!

But even if those pledges are made, it will be essential for UK to work with, and support developing countries in particular, in their transition to zero carbon futures – given all the societal issues and political stresses that will arise.

International treaties are sometimes criticised for being ineffective, and this book describes some of their flaws. How valuable have treaties been in nature conservation?

Well, for those involved in any human endeavour, it’s always easy to see how things could be improved, or work better, and international treaties are no different. But despite imperfections, these treaties are critically important in shaping how we do conservation – in particular in establishing collective long-term objectives – goals that stretch beyond the short-termism of national politics.

Yet whilst the legal treaties specify those things that need to be done to deliver their objectives, as important in the long-term is the community of practitioners that gather around a treaty, regularly meeting and working together in order to drive forward its implementation. This includes counter-part government officials in the signatory governments, relevant NGOs, interested academics, and representatives of different but related treaties. All bring something to the table, and it is through their collective support for, say wetland conservation in the case of the Ramsar Convention, that is so important.

This is the first title from NHBS’s new publishing imprint, Biodiversity Press.

International Treaties in Nature Conservation:

A UK Perspective

By: David A Stroud et al.

Paperback | May 2021 | £19.99

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.

James Lowen is an award-winning writer whose work is regularly featured in The Telegraph, BBC Wildlife and Nature’s Home, among other publications. He is also an editor, lecturer, consultant and keen photographer.

James Lowen is an award-winning writer whose work is regularly featured in The Telegraph, BBC Wildlife and Nature’s Home, among other publications. He is also an editor, lecturer, consultant and keen photographer.

fragile creatures flying a thousand-plus miles). There’s wackiness too: china-mark moths, whose caterpillars live underwater; Sandhill Rustic, whose adults can swim underwater; Scarce Silver-lines, which sings from oak trees; various moths that are engaged in an evolutionary arms race with bats; Indian Meal Moth and Wax Moth, whose caterpillars can digest polyethylene and polypropylene (perhaps conceivably hinting at a solution to the global plastics problem?); and even one New World moth whose cells have proved critical for producing the Novavax COVID vaccine.

fragile creatures flying a thousand-plus miles). There’s wackiness too: china-mark moths, whose caterpillars live underwater; Sandhill Rustic, whose adults can swim underwater; Scarce Silver-lines, which sings from oak trees; various moths that are engaged in an evolutionary arms race with bats; Indian Meal Moth and Wax Moth, whose caterpillars can digest polyethylene and polypropylene (perhaps conceivably hinting at a solution to the global plastics problem?); and even one New World moth whose cells have proved critical for producing the Novavax COVID vaccine. sun-loving, day-flying moth. I guess the other thing to emphasise is that whereas moth-trapping in your garden makes for gloriously lazy wildlife-watching, simply flick the switch and let the insects come to you, surveying moths in remote places is contrastingly hard work. After a long drive, often on the back of little sleep, you need to lug heavy generators and a fleet of moth traps up steep slopes or across difficult terrain. And then you need to stay alert all night to make sure you don’t miss anything. I didn’t get much sleep that year…

sun-loving, day-flying moth. I guess the other thing to emphasise is that whereas moth-trapping in your garden makes for gloriously lazy wildlife-watching, simply flick the switch and let the insects come to you, surveying moths in remote places is contrastingly hard work. After a long drive, often on the back of little sleep, you need to lug heavy generators and a fleet of moth traps up steep slopes or across difficult terrain. And then you need to stay alert all night to make sure you don’t miss anything. I didn’t get much sleep that year…  intrepid endeavours to safeguard

intrepid endeavours to safeguard

I first visited as a schoolboy in 1962, just a couple of years into Skomer’s incarnation as a nature reserve, and it was a day that changed my life forever. The most overwhelming idea that stayed with me from that day was that eventually, whatever it took, I would become warden of Skomer. I finally fulfilled that long-held childhood dream in the spring of 1976. Following 10 wonderful years on Skomer I moved to North Wales where initially I was responsible for the management of 5 spectacular National Nature Reserves and in 1991, I became responsible for supervising the management of the entire series of NNRs in Wales, a position I held for over twenty years. In 2018 I became the chair of the Pembrokeshire islands conservation advisory committee and so my commitment to Skomer continues.

I first visited as a schoolboy in 1962, just a couple of years into Skomer’s incarnation as a nature reserve, and it was a day that changed my life forever. The most overwhelming idea that stayed with me from that day was that eventually, whatever it took, I would become warden of Skomer. I finally fulfilled that long-held childhood dream in the spring of 1976. Following 10 wonderful years on Skomer I moved to North Wales where initially I was responsible for the management of 5 spectacular National Nature Reserves and in 1991, I became responsible for supervising the management of the entire series of NNRs in Wales, a position I held for over twenty years. In 2018 I became the chair of the Pembrokeshire islands conservation advisory committee and so my commitment to Skomer continues.

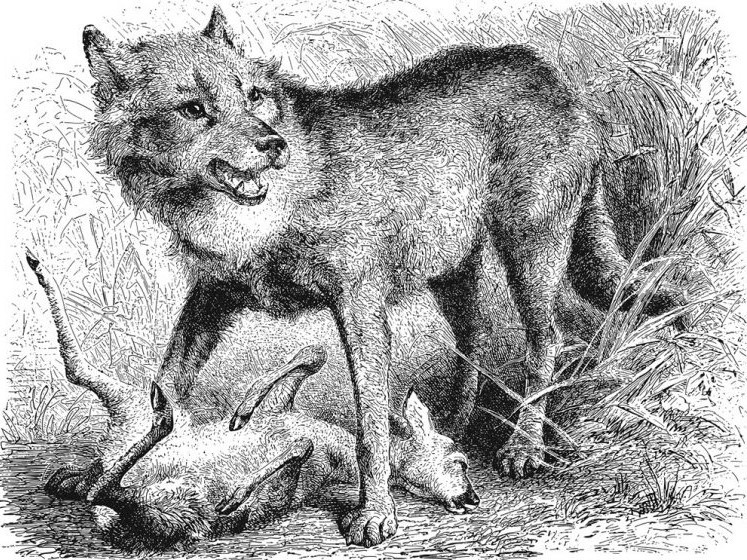

With the recent return of the white-tailed sea eagle to Britain and the mooted return of the Lynx, living with predators is becoming a much more frequent topic of conversation. In

With the recent return of the white-tailed sea eagle to Britain and the mooted return of the Lynx, living with predators is becoming a much more frequent topic of conversation. In  beautiful pictures were covering over a fractured, damaged world. Wild creatures are struggling to make their lives work in our increasingly human-dominated landscapes, and this rich, vibrant planet is thinning out. Over the years the press releases I read, particularly from Ireland, highlighting the decline of curlews were eye-watering. It ate away at me, this relentless destruction, and I decided I had to get more involved. Not so much in the fieldwork and practicality, but in doing what I had been trained to do – tell the stories of the earth and help make the problems accessible and understandable to people like me, non-specialists who care.

beautiful pictures were covering over a fractured, damaged world. Wild creatures are struggling to make their lives work in our increasingly human-dominated landscapes, and this rich, vibrant planet is thinning out. Over the years the press releases I read, particularly from Ireland, highlighting the decline of curlews were eye-watering. It ate away at me, this relentless destruction, and I decided I had to get more involved. Not so much in the fieldwork and practicality, but in doing what I had been trained to do – tell the stories of the earth and help make the problems accessible and understandable to people like me, non-specialists who care.

Formed in 2010, the core aim of the

Formed in 2010, the core aim of the  Sadly there are many threats to badgers and, despite gaining legal protection in 1992, badger persecution is on the increase. In England, one of the biggest threats badgers face is the government licenced badger cull. Since the cull began in England in 2013, a total of 140,991 badgers have been killed, 30,345 of which have been in Devon.

Sadly there are many threats to badgers and, despite gaining legal protection in 1992, badger persecution is on the increase. In England, one of the biggest threats badgers face is the government licenced badger cull. Since the cull began in England in 2013, a total of 140,991 badgers have been killed, 30,345 of which have been in Devon. In 2019, through some very generous grants and donations, the DBG was able to fund two members to train to become licenced lay vaccinators. I was lucky enough to be one of them. Since then, we have worked in collaboration with the Somerset Badger Group to vaccinate badgers in Devon and Somerset, which has allowed us to gain valuable experience. We hope this will continue and expand in the future.

In 2019, through some very generous grants and donations, the DBG was able to fund two members to train to become licenced lay vaccinators. I was lucky enough to be one of them. Since then, we have worked in collaboration with the Somerset Badger Group to vaccinate badgers in Devon and Somerset, which has allowed us to gain valuable experience. We hope this will continue and expand in the future.

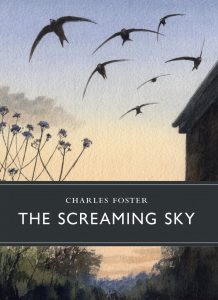

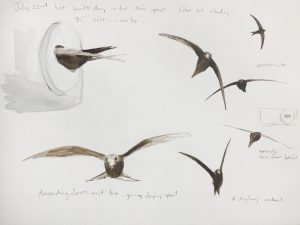

A summer visitor, the common swift appears suddenly with the change in season, swooping overhead with its unmistakeable call. From their travels to Africa, to their short breeding season in the UK, swifts appear to defy gravity with their extraordinary migratory feats, with some in flight for ten months of the year. In

A summer visitor, the common swift appears suddenly with the change in season, swooping overhead with its unmistakeable call. From their travels to Africa, to their short breeding season in the UK, swifts appear to defy gravity with their extraordinary migratory feats, with some in flight for ten months of the year. In

From the Sunday Times bestselling author of

From the Sunday Times bestselling author of