RSPB How to Photograph Garden Birds is an inspirational and practical guide to photographing birds in your own garden. Packed full of tips and tricks, the book covers equipment, composition, light and weather, as well as providing guidance on feeding birds to make your garden as attractive as possible to feathered visitors.

RSPB How to Photograph Garden Birds is an inspirational and practical guide to photographing birds in your own garden. Packed full of tips and tricks, the book covers equipment, composition, light and weather, as well as providing guidance on feeding birds to make your garden as attractive as possible to feathered visitors.

The second half of the book contains a range of different projects, each with details on the equipment required and the techniques you will need to use to obtain the desired shot. From using reflecting pools and catching birds in flight, there is plenty here to help you hone your skills and start capturing professional quality images.

Mark Carwardine is a zoologist and an award-winning writer, a TV and radio presenter and a bestselling author of more than 50 books. Well known for his skills as a wildlife photographer, he was selected as one of ‘The World’s 40 Most Influential Nature Photographers’ in the US’s Outdoor Photography magazine and is currently presenting and producing the BBC Wildlife Photography Masterclass on YouTube. He also runs wildlife photography holidays and workshops worldwide.

In this Q&A, we chatted with Mark about the book, about his life and journey as a photographer, and discuss some tips on making photography affordable.

You have been described as one of ‘The World’s 40 Most Influential Nature Photographers’, have chaired the judging panel of the prestigious Wildlife Competition of the Year for seven years, and are presenter and producer of the BBC’s Wildlife Photography Masterclass. With all this experience, variety and skill under your belt, what made you turn your attention to garden birds as the subject of your latest book?

It was a lockdown thing. I’ve been feeding birds in the garden for as long as I can remember (as we should all be doing – there is a lot of evidence that feeding garden birds year-round really does give them a better chance of survival). I loved watching them, and they gave me an inordinate amount of pleasure, but it was only during lockdown that I really started to photograph them. And then I got completely hooked. Garden birds make fantastic photographic subjects. Many of them are strikingly beautiful; they are readily accessible (you can even capture frame-filling images from your kitchen window); they tend to be tamer and more relaxed around people than most ‘wild’ birds out in the countryside; and they are impressively adaptable (you can move the feeders around, change the perches or add a new prop and they will often return within a few minutes). The other great advantage, of course, is there is no need for flights or hotel rooms: you barely have to leave the house.

What came first to you as a youngster, a love of nature or a love of photography? Or did they develop simultaneously?

Definitely a love of nature. I’ve been obsessed with wildlife since before I could walk and talk. The photography came in my teens. My father was a keen photographer and taught me how to print black-and-white prints in his darkroom in the loft etc, so he was the initial inspiration. I still remember saving for my first ‘proper’ camera in my mid-teens – it took me two years, working every Saturday and all school holidays in a camera shop. I’ve been very lucky to be able to make photography a big part of my work – to illustrate books, articles and lectures etc.

You mention in the book that you started out by shooting film. Do you prefer the flexibility of digital photography or are there things you miss about using older techniques and equipment?

I don’t miss anything about shooting film at all! How anyone managed to take great wildlife pictures with a 36-exposure roll of 25 or 64 ASA film – let alone with a separate light meter and a manual-focus lens – I will never know. I’m very grateful to have learnt photography using film, because you had to understand how everything worked and you had to work slowly and carefully, but my photography has certainly improved since the advent of digital. In fact, I was Chairing the Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition during the transition from film to digital and watched the standard of wildlife photography grow exponentially.

I imagine a large part of being a good photographer is slowing down and really paying attention, not only to your chosen subject, but to the surroundings, weather, light and other variables. As someone who is evidently extremely productive and busy in your professional life, do you find this aspect of photography enjoyable? Or is it a necessary chore?

It’s the only time I slow down! The funny thing is that I am naturally impatient – I can’t bear wasting time. I hate sitting in traffic, waiting for a late train, being trapped in a meeting that is dragging on unnecessarily. But I can happily sit quietly for hours – no, days – waiting for an animal to appear or do something interesting. That’s a pleasure and in no way a chore. I can sit perfectly still in a hide, without moving, let alone talking, with no problem at all. Every sense is alert, your mind clears and, of course, there is always something to look at. The other thing I love is the sense of anticipation. You could wait all day and nothing happens; or, without warning, you could be surprised by one of your best wildlife sightings ever. And, of course, you do need to be patient in wildlife photography, waiting for the best light, the best pose, or whatever.

Do you think that art and photography have an important role to play in inspiring people to value or get involved with wildlife and the natural world?

I have mixed feelings about this. I do think photography can play a critically important role in inspiring people and promotion conservation. The old adage ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ is often true – meaning that complex ideas can be conveyed in a single image. There are many examples of one picture spurring a massive campaign and, ultimately, inspiring significant change. On the wall behind me in my office is a signed photograph by Commander Frank Borman, taken during Apollo 8, the first manned mission to the moon. It’s called ‘Earthrise’ and shows our tiny blue planet hanging in space, as viewed across the surface of the moon. It’s credited with kick-starting the environmental movement in the late 1960s. There are some inspiring examples in nature photography, too. Ansel Adams famously used his photographs to help create Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. And look at the work of the International League of Conservation Photographers. But I have mixed feelings because many photographers these days claim to be ‘helping conservation’ simply by taking pictures of wildlife and wild places. It doesn’t work like that – you have to do something as well.

In the current financial climate, the cost of equipment might put many people off taking up photography as a hobby. I liked that you covered the use of smartphones in your book, as this is something that almost everybody has access to. What would be your top recommendation for an inexpensive accessory that could be used with a Smartphone for photographing garden birds?

Yes, it’s true. Some of the best long lenses these days cost as much as a small family car! There’s a whole chapter in the book about photographing garden birds with a smartphone. One of the challenges with smartphone photography is shooting frame-filling pictures – getting close enough to your subjects. I’d recommend buying a really inexpensive little gadget called a shutter release, or shutter remote. This communicates with your phone via Bluetooth. Once you’ve paired it, you simply tap the button on the remote to take a picture. Then all you do is place the phone near your carefully positioned photographic perch – or wherever you think the birds might land. Sit in the kitchen with a coffee or a beer, using binoculars to see the back of the phone clearly enough to judge when a bird comes into view, and fire away to your heart’s content. It works amazingly well.

What’s in store for you next? Do you have plans for further books?

Actually, I’m working on another photographic book. For the past 30 years, I’ve spent a month or two most winters in Baja California, on the Pacific coast of Mexico, running whale watching tours, doing research and filming. It’s arguably the best place in the world for whale watching. So I am compiling a book of my favourite photographs from those 30 years, called ‘Baja California: Realm of the Great Whales’. I just have a few hundred thousand more images to go through, and I’ll be ready to make the final selection!

RSPB How to Photograph Garden Birds by Mark Carwardine was published in January 2023. It is published by Bloomsbury Publishing and available from nhbs.com.

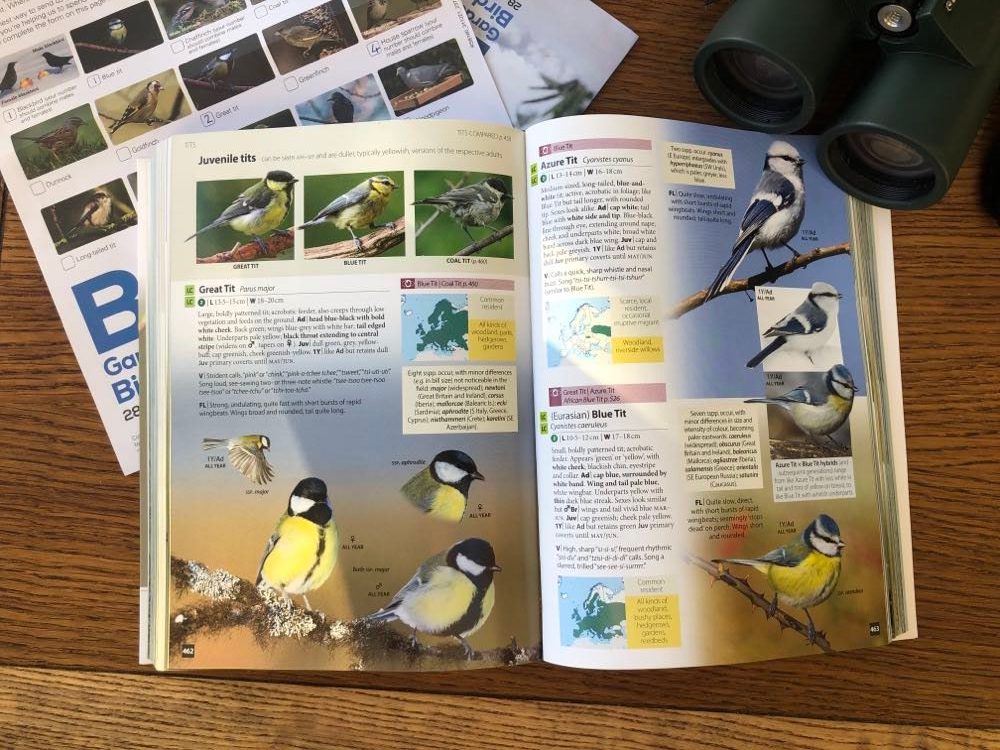

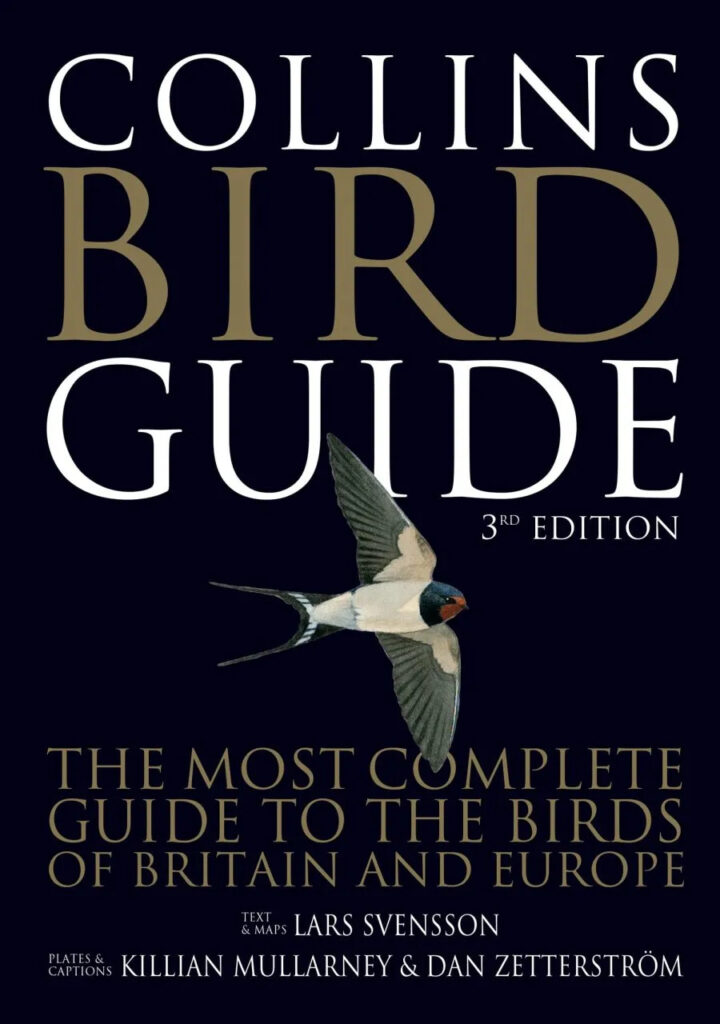

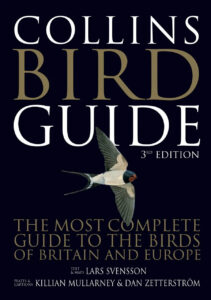

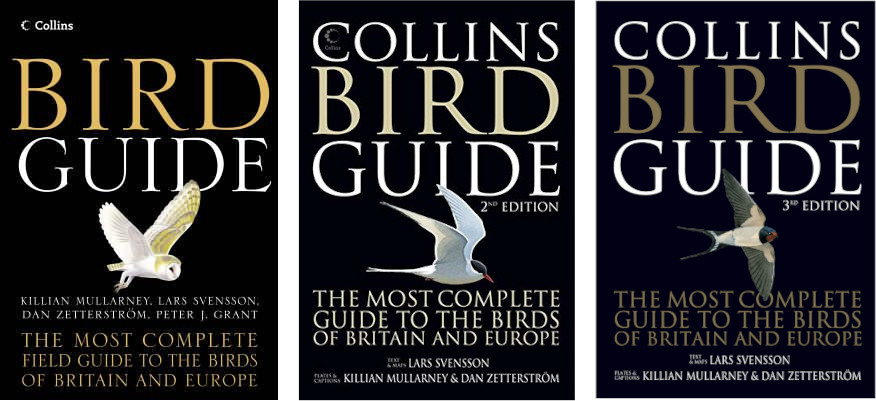

In 1986, well respected identification experts Peter Grant and Lars Svensson came together to begin working on just such a thing. To illustrate the book they recruited artist Killian Mullarney from Ireland, whose painstakingly detailed work was conducted from first-hand field experience, lending it a lively and lifelike quality. Creating artwork in this way, however, proved to be a slow process, and even with the addition of another illustrator- Dan Zetterström – the book was 13 years in the making. Unfortunately, Peter Grant died in 1990, some time before its eventual publication in 1999, so he never got to see the final result.

In 1986, well respected identification experts Peter Grant and Lars Svensson came together to begin working on just such a thing. To illustrate the book they recruited artist Killian Mullarney from Ireland, whose painstakingly detailed work was conducted from first-hand field experience, lending it a lively and lifelike quality. Creating artwork in this way, however, proved to be a slow process, and even with the addition of another illustrator- Dan Zetterström – the book was 13 years in the making. Unfortunately, Peter Grant died in 1990, some time before its eventual publication in 1999, so he never got to see the final result. The second edition of the Collins Bird Guide was published in 2010 to reflect new and revised taxonomy, and included both expanded text and additional illustrations. The

The second edition of the Collins Bird Guide was published in 2010 to reflect new and revised taxonomy, and included both expanded text and additional illustrations. The

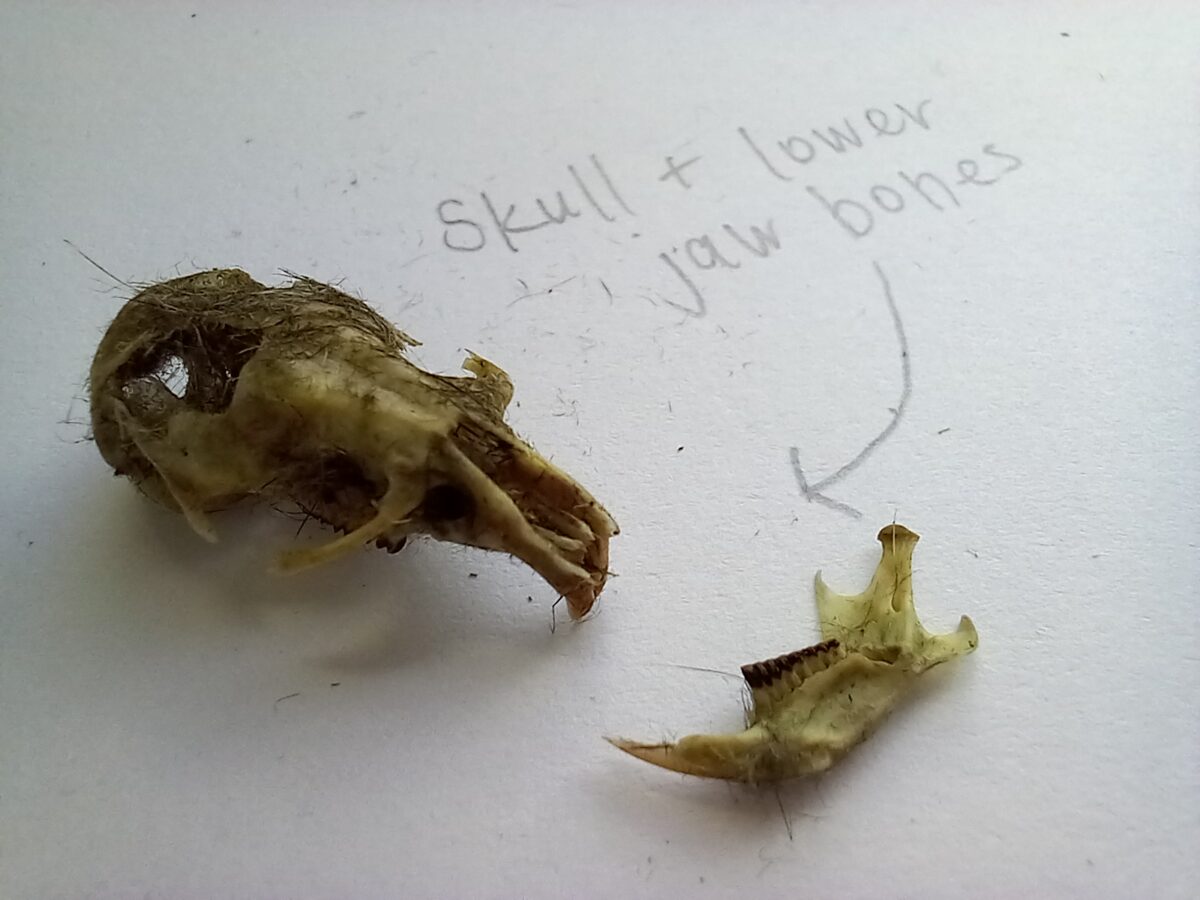

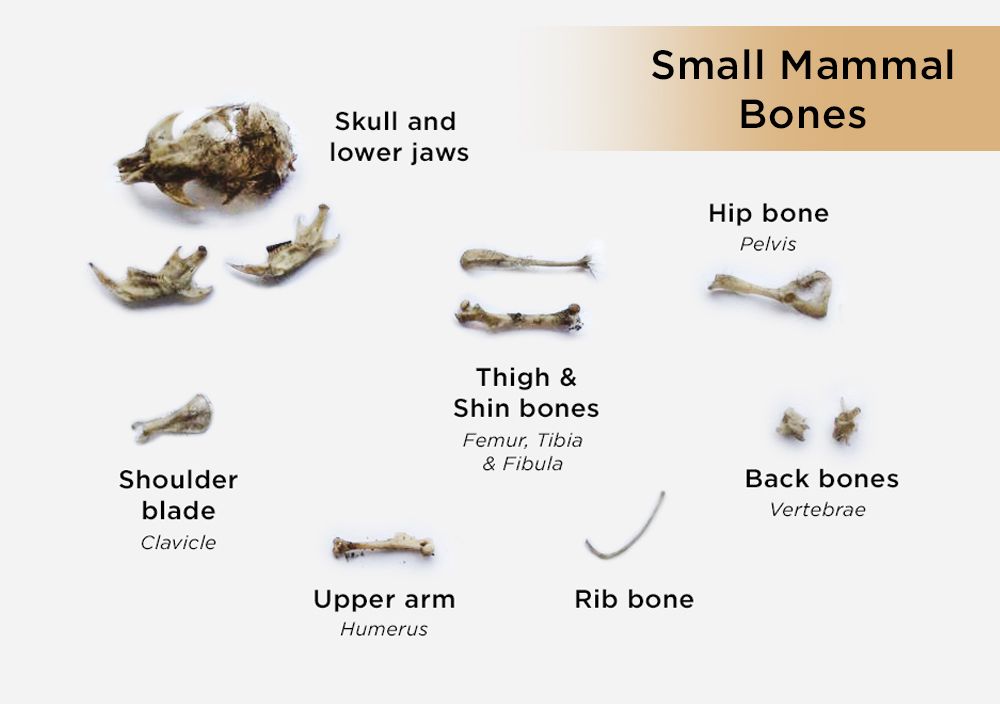

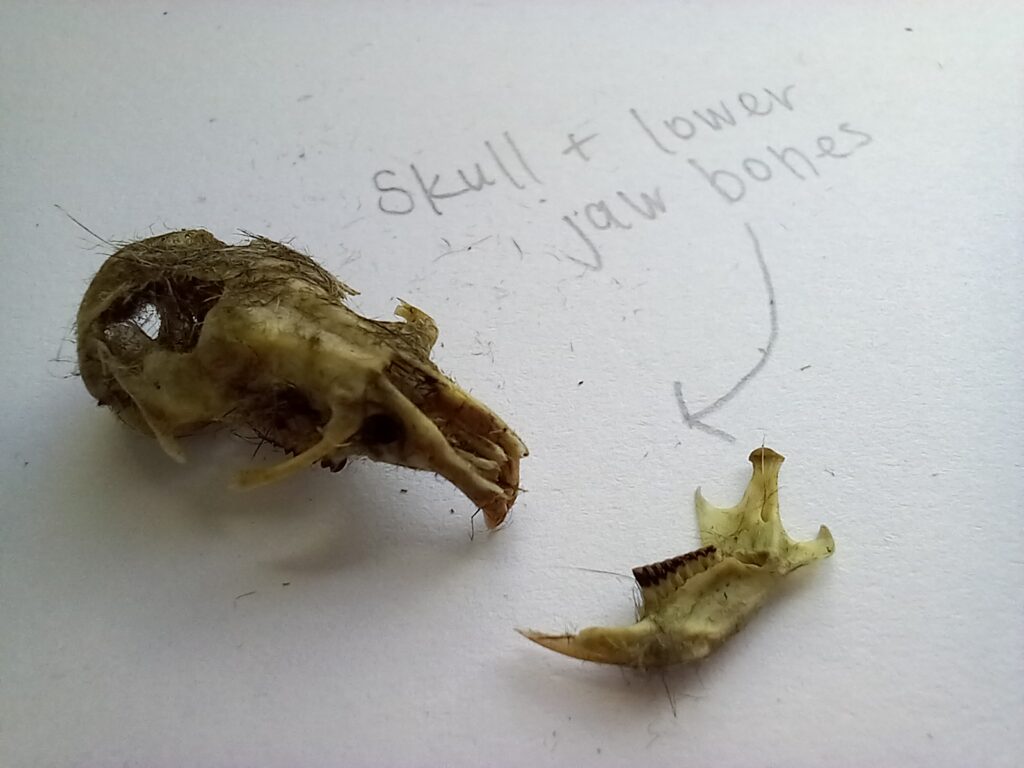

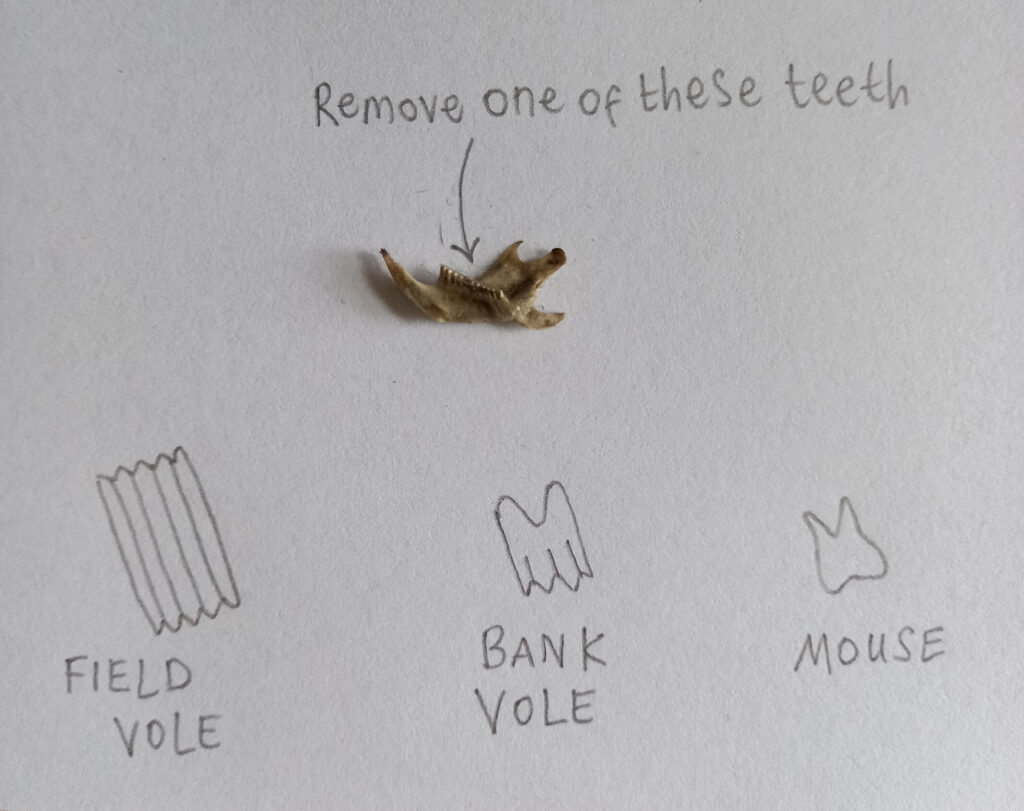

The most useful part of the skeleton for identification is the skull and jaws or beak. Bird skulls will obviously be very distinct from those of mammals due to the presence of the beak, so these can immediately be separated out. For the remaining mammal skulls, however, we will need to take a closer look at their lower jaw bones and teeth.

The most useful part of the skeleton for identification is the skull and jaws or beak. Bird skulls will obviously be very distinct from those of mammals due to the presence of the beak, so these can immediately be separated out. For the remaining mammal skulls, however, we will need to take a closer look at their lower jaw bones and teeth.

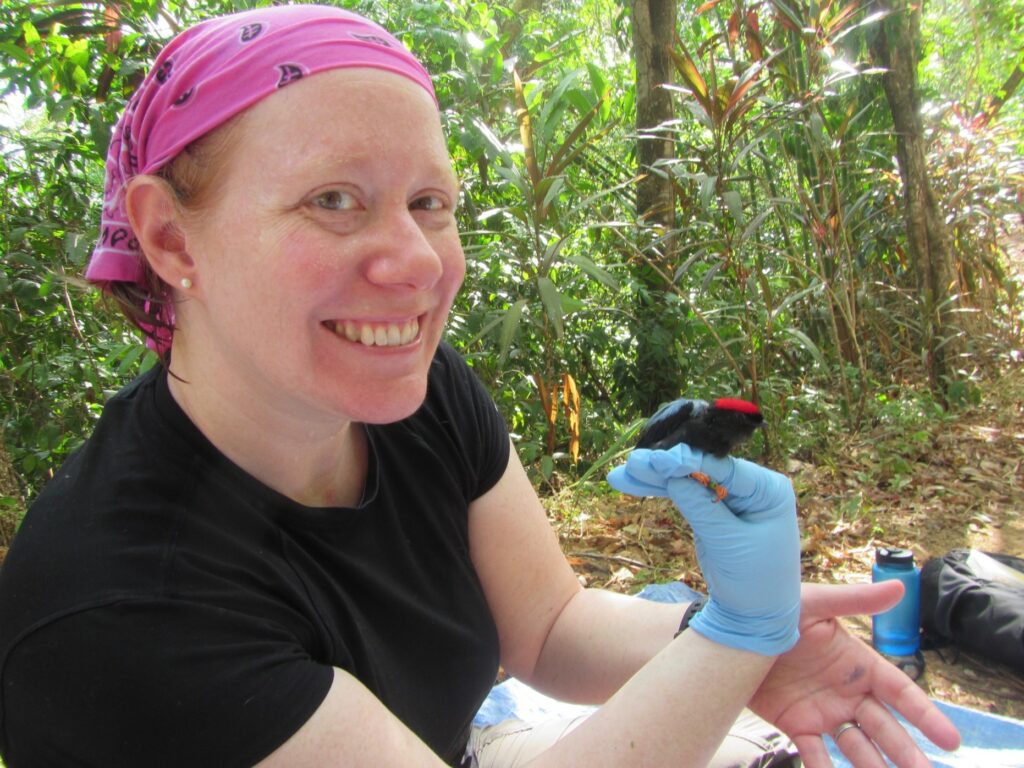

I was originally studying how birds might choose their mates on the basis of certain immune genes, following the idea that animals could prefer mates with different genes than their own, leading to offspring with stronger immune systems. I was struggling to sequence these genes, and I complained to a colleague who happened to be studying bird brains. He said, “I don’t know why you’d study that in birds – information about those genes is sensed by smell, and birds don’t have much of a sense of smell.” I had never heard that before, and the idea that a whole group of animals would lack such an important sense seemed absurd to me. So, I started investigating.

I was originally studying how birds might choose their mates on the basis of certain immune genes, following the idea that animals could prefer mates with different genes than their own, leading to offspring with stronger immune systems. I was struggling to sequence these genes, and I complained to a colleague who happened to be studying bird brains. He said, “I don’t know why you’d study that in birds – information about those genes is sensed by smell, and birds don’t have much of a sense of smell.” I had never heard that before, and the idea that a whole group of animals would lack such an important sense seemed absurd to me. So, I started investigating.