The 2024 South West Marine Ecosystems (SWME) conference was held at the Plymouth Marine Laboratory in April. Running since 2007, the conference brings together organisations and individuals involved in research on and management of the marine environment to report on annual system changes in the south-west. The conference covers the oceanography, plankton, seabed and seashore, fish, seabirds, seals and cetaceans of the south-west. Alongside key trends and interesting occurrences from the past year, SWME also encompasses management themes: marine planning, protected areas, fisheries, water quality and plastic pollution. This year’s theme focussed on the interconnectedness of the environment and its management, demonstrating this connectivity through interaction and discussion between guest speakers. In this blog we provide a roundup of SWME 2024.

Environment

The first session began with a rundown of oceanography and weather conditions across the UK, setting the scene for our marine environment. The UK experienced an increase in mean air temperature and increased sunshine duration over winter. There was also a decrease in mean rainfall across the UK and record-breaking heatwaves – some of us may remember the scorching temperatures of June last year, a worrying 2–3°C anomaly.

From March 2024, a new bylaw prohibits the use of bottom towed gear in defined areas of 13 marine protected areas (MPAs). Hartland Point to Tintagel Marine Conservation Zone (MCZ), Cape Bank MCZ, Lands End and Cape Bank MCZ, South of Celtic Deep MCZ, Wight-Barfleur Reef MCZ, East of Haig Fras MCZ and Greater Haig Fras MCZ are the MPAs that will benefit from this designation in the south-west. Devon Wildlife Trust vocalised a desire for a ‘whole-site approach’ for MPAs in the region – managing the site in its entirety, not just where protected species or features are present.

The Devon Maritime Forum stressed an urgency to address issues surrounding water quality in the south-west. They reported that no single stretch of river was found to be in ‘good’ overall health in 2023 – with quality impacted by agricultural run-off, sewage overflows, climate change and urban diffuse pollution. The UK Government has pledged to invest £1.6 billion to improve the water quality of rivers, lakes and coastal waters. Investments will be used to tackle storm overflow discharges, treatment works pollution and water resilience. South West Water will also be investing £70 million to upgrade infrastructure to reduce discharges in the region.

Analysis of plastic pollution showed that polyethylene was the most common material in plastic waste and marine litter fragments. To tackle the issue of plastic pollution on a global scale, the Global Plastics Treaty is under negotiation, and is expected to be legally binding by 2024. The treaty will address the full life cycle of plastic products and aim to end the pollution by these materials worldwide.

Key points:

- Higher average winter temperatures and sunshine, with decreased rainfall were observed in 2023

- A new bylaw will prohibit the use of bottom-towed gear in seven MPAs.

- The UK Government has pledged to invest £1.6 billion to improve freshwater and coastal water quality

- The Global Plastics Treaty will be legally binding by the end of 2024, intending to end plastic pollution

Organisms

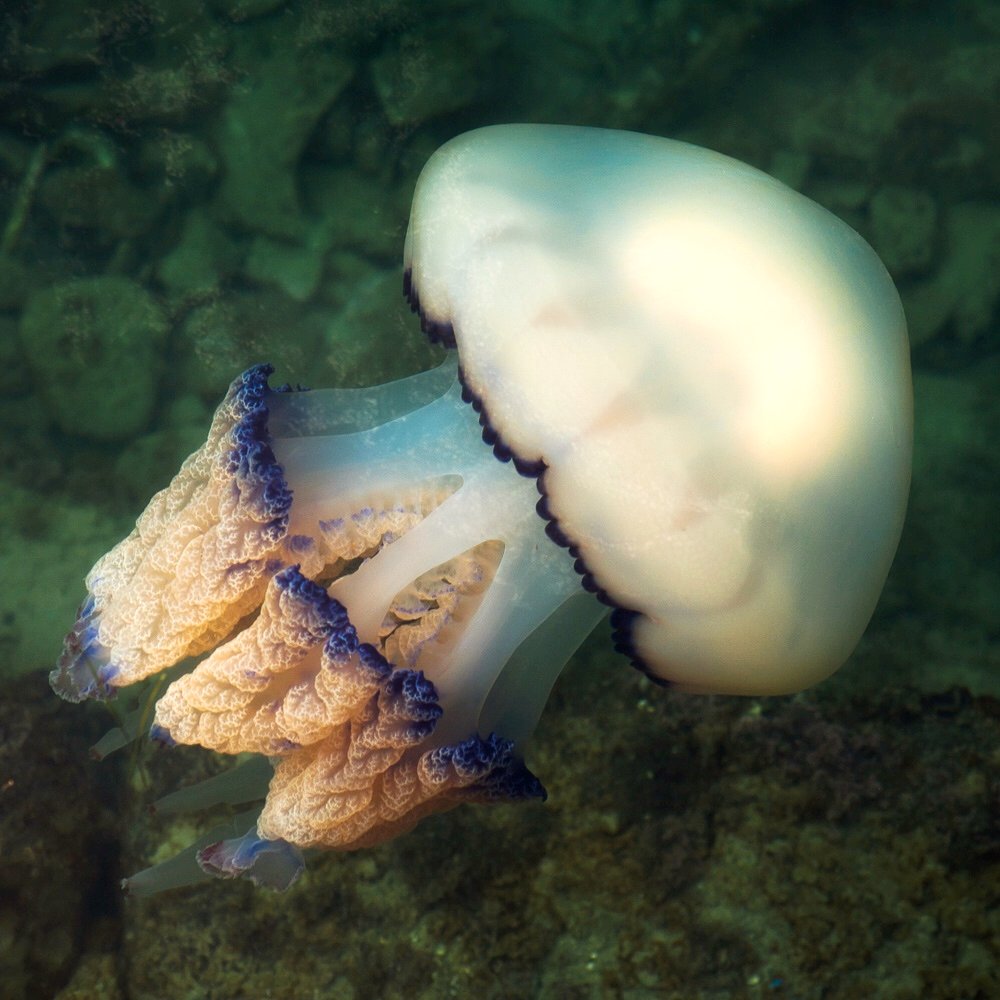

Plankton researchers saw a higher abundance of salps (a barrel-shaped pelagic tunicate), consistent with a general increase in filter feeders over the past 30 years. There was also an influx of Barrel Jellyfish strandings across the south-west, with the species accounting for 27% (467) of the annual total of jellyfish sightings. A new method of plankton sampling has been developed, called Automated In-situ Plankton Imaging and Classification System (APICS). This new technology will help to determine the impacts of environmental changes on plankton, allowing for long-term, broad-spectrum measurements of the group.

New observations have improved our understanding of Basking Shark behaviour, revealing that this species may remain in UK waters throughout winter, instead of migrating south as previously believed. Blue Sharks were also caught more readily than previous years, exhibiting a higher catch per unit effort (CPUE), with over 1,000 caught off the coast of Looe, in Cornwall. The UK had its first sightings of Smalltooth Sand Tiger Shark, with a 10-foot individual washing up in Lyme Regis, Dorset. Typically seen in tropical and temperate waters, the discovery of this species in the UK is indicative of the effects of climate change on marine megafauna. Atlantic Bluefin Tuna have also been returning to the south-west with most sightings between July and February. There has been a marked increase in catch rate (over 5,000 were landed in 2023) which has prompted the introduction of fisheries plans (see below).

Rat eradication has been hugely successful for a number of seabirds. On Lundy, Manx Shearwaters and Puffins have responded positively and have seen population increases in 2023, and Storm Petrels have recolonised the island. Razorbills and Guillemots are also recovering well and are breeding successfully without predation from rats. The south-west has luckily missed the worst of avian influenza, although some small gulls and terns were affected in Dorset last summer. However, Kittiwakes are having local productivity issues which is prompting concern, and several species of gull are experiencing significant declines: Herring Gulls, Lesser Black-backed Gulls and Great Black-backed Gulls have all experienced losses over 40%. The English Seabird Conservation and Recovery Pathway (ESCaRP) report was published at the start of 2024, highlighting the sensitivity of seabird species to a range of pressures. Vulnerability assessments were conducted to inform the recovery pathway, and the report has made recommendations for conservation measures to address negative impacts.

There are concerns over the impacts of climate change on Humpback Whales. Increasingly, we are seeing individuals which are choosing not to migrate and are instead remaining in UK waters. Researchers believe that these animals are not undertaking seasonal movements due to a lack of food resources during winter – demonstrating that decreased productivity at the base of the food chain can cause issues further down the line for other marine organisms.

Key points:

- New technology will provide a greater understanding of the impact environmental change may have on plankton

- Atlantic Bluefin Tuna and shark sightings have increased in the south-west, including the Smalltooth Sand Tiger Shark, never previously recorded in the UK

- Rat eradication programmes have been hugely successful in protecting seabirds

- Kittiwakes and a number of gull species are experiencing declines

- Climate change is thought to be impacting Humpback Whale migration

Industry

The Crown Estate have announced plans to develop more offshore wind farm projects, generating an additional 4GW of electricity to contribute to the 50GW by 2030 goal. This additional capacity could power up to four million homes, contributing to the UK target of net zero by 2050. Large, floating platforms have been proposed to enable deployment in deeper water – installation further offshore provides more reliable wind resources, generating more power for the same installation on-shore. There have been assessments to prepare for the deployment of extensive offshore wind in the south-west – with pre-consent surveys run by The Crown Estate. Celtic Sea Power, owned by Cornwall Council, is supporting offshore roll-out and has identified areas for data collection in the region. There are three project development areas where aerial, geophysical, acoustic and LiDAR surveys are taking place to improve data collection, accelerating the programme. The Poseidon Project was established by Natural England to provide a sensitivity map across the EEZ (exclusive economic zone –a surrounding area of 200 nautical miles offshore, where the nation has jurisdiction over resources) through digital aerial surveys. Collecting detailed information on seabirds, marine mammals and habitats, the project aims to improve models of abundance and distribution for key species which may be impacted by offshore development.

Sardine and Anchovy stocks are reported to have had a good year, continuing to support fisheries in the south-west, while Sprat fisheries have slowed due to insufficient stock size and 0-group fish (fish in their first year of life). We can see that new fisheries are emerging in the region (e.g. Atlantic Bluefin Tuna quota of 39 tonnes), while other, more traditional stocks are declining (e.g. Edible Crab). Five fisheries management plans have been developed for bass, King Scallops, crab and lobster, whelk and non-quota demersal species – these plans are put in place to deliver sustainable fisheries while minimising negative impacts on marine species. Dogger bank SAC, The Canyons MCZ and Inner Dowsing, Race Bank and North Ridge SAC were protected from damaging fishing activity in 2022 by prohibiting trawls, seines, dredges and bottom towed gear – this bylaw seeks to protect cold-water coral reefs, seabed, sandbanks and biogenic reef.

Key points:

- Offshore wind development is being accelerated by better data collection and availability, supporting the UK in reaching renewable energy targets

- Some traditional stocks are declining, while new fisheries are emerging

- Five fisheries management plans were introduced

- Four areas of conservation concern were protected to prohibit bottom towed gear

This year’s conference was an enlightening insight into the marine ecosystem in the south-west and highlighted some inspirational conservation work undertaken by several organisations, and individuals, dedicated to this environment. The SWME YouTube channel has a selection of webinars and further information on the conference can be found on the SWME website.