Coastal sand dunes are habitats created by sand, seashell fragments and other sediments that are moved by wave and wind action along a coastline or beach until they become trapped above the strandline. This usually occurs where vegetation is growing as their roots and leaves help to bind the sand together, preventing the sand from being blown away by the wind. There are several different types of sand dunes, categorised by their position on the shoreline, age, morphology and stability:

- Embryo dunes: The youngest dunes at their earliest stage of development, usually closest to the shore and may still be covered by high tides. This area usually has high salinity and is a very dry environment with rapid drainage and a lot of exposure.

- Mobile dunes: These are dunes that are no longer covered by the highest tide but are still affected by wind; sand gets blown from the beach onto, over and away from these areas.

- Semi-fixed dunes: This is where vegetation cover has become more continuous with fewer areas of bare sand.

- Fixed dunes: These are dunes that have very limited free space, with few areas of bare sand and almost continuous vegetation.

- Dune slack: The low-lying depressions between sand dunes. These areas can often become filled with fresh or brackish water, creating small wetlands known as interdunal wetlands or interdunal ponds. These areas can warm quickly as they’re often very shallow, providing an ideal habitat for many invertebrates.

- Dune scrub: A later successional stage, where a stable dune has been colonised with scrub species. These areas can continue to develop into dune-heath and older woodland.

Sand dunes can be rich in wildlife and are important habitats for birds, reptiles, invertebrates, a variety of plant species, lichens and fungi. This is particularly the case in older, more stable dune habitats. They are classified as UK BAP Priority Habitat and several Priority List species have been recorded utilising sand dunes.

What species can you find here?

Flora

Differences in flora diversity can be found depending on the position, age, morphology and stability of the dunes. Sand dunes that are still inundated at high tide can be dominated by halophilic (salt-tolerant) plants, whereas dune slack areas may be filled with fresh groundwater, allowing them to support several freshwater plant species. Areas of low stability will most likely see lower plant diversity, with the community present dominated by pioneer species. More stable dunes are generally dominated by woody plants and have higher diversity.

Sea sandwort (Honckenya peploides)

This is one of several pioneer species usually found in embryo dunes, as it is highly stress-tolerant. These plants allow sand to begin to accumulate, raising the top of the dune above the high tide level, while also adding organic matter to the sand through dying and decaying. This allows the sand dune to better retain water, allowing other plants to colonise the area.

Marram grass (Ammophila arenaria)

This is a dune building grass as it is tall and robust, with matted roots, therefore it is very effective at trapping and stabilising sand. It can help to form very high mobile dunes as it grows at a rate of 1m per year. It is usually the dominant plant on mobile dunes and is a familiar sight on many of our coasts. By stabilising the sand and adding nutrients through its dead leaves, this plant can allow sand dunes to be colonised by many other plant species.

Harebell (Campanula rotundifolia)

As sand dunes become more fixed and vegetation cover becomes more continuous, the area can be very species-rich. Many wildflowers, including harebells, can be found there, providing a food source for species such as invertebrates. Due to the wide range of environmental factors in these habitats, such as wind, salinity levels and availability of shelter and fresh water, there is often a huge variety of wildflowers.

Harebells, also called bluebells of Scotland, are tough and resilient plants, living in dry, open areas such as sand dunes. While their flowering period can vary, it’s usually from July to November in the British Isles, providing a vital source of nectar for bees during the autumn.

For more examples of wildflowers, check out our guide to UK wild flower identification.

Silver birch (Betula pendula)

The final successional stages of sand dunes include colonisation by woody plants, creating dune scrubs and, finally, deciduous woodland. These woodland are often lower in species diversity, as woody species out-compete others, but the habitat will remain stable for extended periods, barring any disturbance. The type of vegetation present in the climax stage is determined by a number of factors, such as climate, exposure, soil pH, grazing level and management type. Birch trees are one of the woody species that can colonise sand dunes, particularly acidic dunes with open areas for young birch trees to grow.

Fungi

While fungi are usually associated with damper habitats, there is a variety that can be found in sand dune habitats, such as the earthtongue fungus (Glutinoglossum glutinosum), dune stinkhorn (Phallus hadriani) and several puffball species. There are also rare species that can only be found in sand dunes.

Dune waxcap (Hygrocybe conicoides)

This species of waxcap occurs mainly on short grass in coastal sand dune habitats, such as on the edges of dune slacks. Waxcaps, fungi in the genus of agarics, or gilled fungi, are usually brightly coloured fungi with dry to waxy caps. They are mainly associated with unimproved grasslands, though outside of Europe they are more commonly found in woodland. Dune waxcaps resemble the blackening waxcap (Hygrocybe conica) when young, but older dune waxcaps only darken slightly, usually just on their stem, unlike the blackening waxcap.

Collared Earthstar (Geastrum triplex)

While collared earthstars are most likely found in woodlands, particularly those with a high level of leaf litter, they can also be found on sand dunes. This star-shaped fungus initially looks like a ball, similar to a puffball, before splitting open. Other earthstars, including the dwarf earthstar (Geastrum schmidelii), can also be found in sand dune habitats, particularly mature sand dune systems. They’re often found in colonies with several fruitbodies growing together.

Fauna

Sand dunes support a diverse range of fauna species, many of which are specifically adapted to live in these dynamic habitats. Similarly to shingle beaches, which will be covered in another article, this area is a key habitat for several ground-nesting birds, such as the Ringed Plover and Skylarks, grazing species such as rabbits, and invertebrates such as bees, digger wasps and other insects.

The red-banded sand wasp (Ammophila sabulosa)

Sand wasps reproduce by hunting caterpillars, paralysing them using their sting and burying them in burrows with the sand wasp’s egg. The females dig their burrows in sandy ground, with a nearby area of vegetation that would support their prey. Areas of sand dunes can be rich in invertebrate species, particularly where diverse vegetation is present.

Northern Dune Tiger Beetle (Cicindela hybrida)

This rare beetle hunts on bare sand, preying on ants, spiders, moth larvae and flies. As they need areas of open, moving sand, they are less likely to be found in older, more stabilised sand dunes. Therefore, lack of management allowing succession and reduced sediment deposition due to development or flood defences reduce the availability of suitable habitats. Conservation efforts to restore mobile sands and remove areas of scrub are helping to provide more habitats for the northern dune tiger beetle.

Sand lizard (Lacerta agilis)

Sand dunes support a variety of vertebrate species, including the sand lizard, one of the UK’s rarest reptiles. Their distribution is restricted to a small number of sites, such as protected heathlands and sand dunes. They require sunny habitats with vegetation for shelter and undisturbed, open sand to lay their eggs. Their numbers are impacted by habitat loss but there are several conservation efforts working towards increasing their populations. These involve a combination of habitat restoration, monitoring, reintroduction and encouraging beneficial policies and practices.

Sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus)

Several birds of prey use sand dune habitats as hunting grounds due to the presence of ground-nesting birds, lizards and some grazing species such as rabbits. Sparrowhawks can be found across Britain and Ireland, mainly in gardens, woodland and urban settings, but they can also be found on sand dunes, particularly if woodland is close by. They prey mainly on small birds, but they have also been recorded taking bats.

Chough (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax)

Once extinct in Britain, Choughs now have a growing population on the Cornish and Welsh coasts, as well as a few other spots around the UK. They hunt invertebrates and larvae in the exposed sandy soils of sand dunes, using their long, curved bills. With only a small population in the UK, it is important to maintain suitable areas of habitats, therefore a number of projects are reintroducing grazing species to dunes. These species help to maintain areas of open ground and short grass, preventing sand dunes from becoming scrubland.

For more information on other species that may occur in sand dune habitats, including reptiles, coastal birds, waders and other mammal and bird species, check out some of our other guides to UK species identification.

Threats

The main threats to coastal sand dunes are development, recreational use, flood defences, falling water tables, climate change, invasive species and poor management. The development of housing, industry and areas such as golf courses can result in the damage or destruction of sand dune habitats. This, along with recreational use, such as excessive pedestrian and vehicular use, can increase levels of erosion and modify vegetation. Fragile sand dune habitats can be altered, reducing their stability and their ability to support diverse wildlife.

Poor management allows encroachment by shrubs and trees that, if left unchecked, could turn sand dune habitats into woodland areas, which can impact their suitability for specialist species. Flood defences can impact the natural processes of sediment removal and deposition, which can prevent sand dunes from developing or growing. These areas can become depleted if there is not enough sediment deposited to replace the amount removed by wind or wave action. The creation of harbours and other coastal structures can also disrupt natural sediment processes. Alternatively, these structures can also prevent sediment removal, causing a build-up of sediment.

Further threats include invasive species, such as cordgrass (Spartina anglica), which can dominate sand dunes, reducing the abundance and diversity of native plant species and reducing the number of animals that the area can support. Climate change can also threaten this habitat, as increasing intensity and frequency of storms can impact how sand dunes are formed. Sea-level rise, in combination with development, can also reduce the amount of area available for this habitat to form; this is termed coastal squeeze.

While grazing is used as a method for controlling over-stabilisation and succession, overgrazing can also impact sand dunes. It can reduce the development and spread of vegetation, preventing sand stabilisation and, therefore, reducing the diversity and abundance of the species the habitat can support. This also allows sand dunes to become depleted by wave or wind action, particularly where structures such as flood defences and development have reduced sediment deposition.

Conservation

To manage the impacts of these threats, many sand dune areas have been given Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) designations, which control the amount of development that can occur. Soft engineering approaches to flood defences including beach replenishment, the restoration of stabilised sand dunes and managed realignment, where areas are allowed to be inundated by the sea, can often be a more natural approach to reducing the impacts of waves compared to hard engineerings, such as sea walls and breakwaters. These can allow the natural process of sediment removal and deposition, facilitating the development of new sand dune environments.

As mentioned, sand dunes are subject to natural habitat succession, often ending in a stable deciduous woodland habitat. To maintain sand dune habitats, encroachment by woody species must be controlled and areas of open, mobile sand should be created as this prevents soil development and, therefore, over-stabilisation.

Areas of significance

Lindisfarne National Nature Reserve, Northumberland

Braunton Burrows, North Devon

Holkham NNR, North Norfolk

Kenfig NNR, Glamorgan, South Wales

Forvie NNR, Aberdeenshire, Scotland

Further reading

The Biology of Coastal Sand Dunes

Coastal zones are becoming increasingly topical as they face relentless pressure from a number of threats. This book provides a comprehensive introduction to the formation, dynamics, maintenance and perpetuation of coastal sand dune systems.

Sand Dune Conservation, Management and Restoration

Sand Dune Conservation, Management and Restoration

This book deals with the development of temperate coastal sand dunes and the way these have been influenced by human activity. Options for management are considered and the likely consequences of taking a particular course of action highlighted.

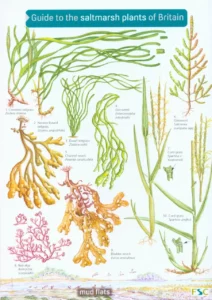

Field Guide to Coastal Wildflowers of Britain, Ireland and Northwest Europe

Field Guide to Coastal Wildflowers of Britain, Ireland and Northwest Europe

This field guide covers more than 600 species of wildflowers and other coastal flora found in Britain and Ireland, and coastal mainland north-west Europe. Detailed species accounts describe the wildflowers, grasses, sedges and rushes that occur on the coast or in abundance within sight of the sea.

Wildflowers of the Sefton Coast

Wildflowers of the Sefton Coast

This book describes the typical wildflowers associated with each of the Sefton Coast’s main habitats from the saltmarshes and ‘green beaches’ to the sand-dunes; the latter showing a sequence of successional stages running inland, from the newly-formed strandline and embryo dunes, through mobile and fixed-dunes to older woodland and dune-heath.

A new edition of a unique textbook that provides an exhaustive treatment of the world’s different coasts, with a focus on climate change sea-level rise. Seeking to better educate students and readers about the sustainability of coasts and coastal environment, this exciting book offers enlightening coverage of coastal geology, processes and environments.

This new edition continues the theme of the first edition: the need to restore the biodiversity, ecosystem health, and ecosystem services provided by coastal landforms and habitats, especially in the light of climate change. This will be valuable for coastal scientists, engineers, planners, and managers, as well as shorefront residents

Sea of Sand: A History of Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Sea of Sand: A History of Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

The Great Sand Dunes sprawl along the eastern fringes of the vast San Luis Valley of south-central Colorado. Sea of Sands is the definitive history of the natural, cultural, and political forces that helped shape this incomparable landscape.