Many of us delight at butterflies visiting the flowers in our gardens, be it the drunken admirals of autumn or the spritely orange-tips in spring, yet some of us still seem to shudder at the thought of dingy moths bothering our windows at night or worse still munching our clothes to dust in our cupboards. In the middle of June, armed with two moth traps and a couple of trusted field guides, I attended an open garden in Somerset ready to join the #Mothsmatter conversation initiated by Butterfly Conservation to dispel the moth myths and encourage a fascination for these insects.

Setting up a Skinner moth trap in a covered porch over a couple of cold nights, I wasn’t entirely sure what species would be flying, but sure enough in the morning as I lifted the lid and slid the egg boxes out, there were some delightful species to see. Visitors in the garden were suffice to say, in awe of the moths the light brought in; the Poplar Hawk-moth and the Eyed Hawk- moth, the Fox Moth with his rabbit ear antennae and the remarkable Buff-tip.

We are becoming well aware that UK moths are in decline with an overall decrease in numbers by 28% since 1968, and over 60 species becoming extinct in the 20th century. Moths are a key indicator of environmental health and, as vital as they are to other creatures as a food source (their declines are impacting on breeding birds and bats) they are also vital for the pollination of native flora, an essential element to the tapestry of wild life. There is also evidence to suggest that climate change is shifting the habitable ranges of many of the moths that call the UK home, and while this can produce some spectacular species visiting from continental Europe, many of the species that have relied on the temperate climate in the UK are being forced out northward.

With a recent trend in wildlife gardening and more strict rules on chemicals used in agriculture, there is hope however that we can retain and rebuild some of the moth populations that are so vital in our countryside. Butterfly Conservation have a wealth of information available on their website about the trends of moth populations and, very importantly, what you can do to take action, join the conversation and promote moths at https://butterfly-conservation.org/moths/why-moths-matter

If you are interested in learning about which moth species are visiting your garden or local wild places, light trapping is simple and loads of fun. At NHBS we supply a range of moth traps suited for a number of habitats and a wide selection of amazing field guides to aid in identifying the moths you find. Below we have listed some of our favourite traps and provided a little more information on the differences between them, however if you wish to see our full selection of moth traps please visit our website.

Robinson Moth Traps

These large traps are renowned among lepidopterists because they offer the highest attraction and retention rates available. These traps are fitted with either mercury vapour or actinic electrics. Mercury vapour bulbs offer greater brightness than actinic bulbs and consequently they will often attract more moths. However actinic electrics may be favourable in areas where the brighter bulbs may cause disturbance; they also run cold and do not need to be shielded from rain, unlike mercury bulbs which are likely to shatter when used without a rain guard.

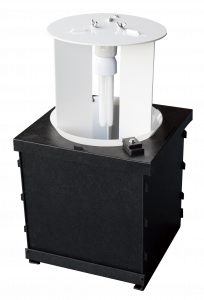

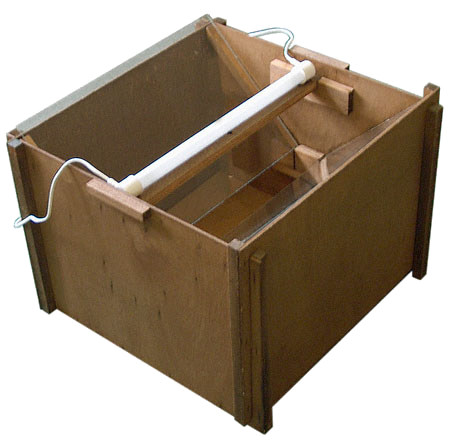

Skinner Moth Traps

These traps are precursors to the Robinson, and as well as being a more economic choice, they allow the catch to be accessed while the trap is running. They feature a plastic or wooden box with a light fitted to a cross member above a long slit through which moths fall and become trapped. A highlight of this box are the transparent panels that make up the trap lid. These can be removed to access the catch while the trap is running, which is great for real-time surveys and demonstrations. These traps can be easily collapsed down for easy storage and transport.

Compact 20W Skinner Moth Trap (240V)

* Price: £179.00 inc VAT

* Dimensions: 32 (h) x 35 (w) x 35 (d) cm

* Weight: 3kg

* Electrics: 240V mains electric

* Alternative battery-operated units also available.

Heath Moth Traps

These traps are favoured for their lower cost and compact design which makes them highly portable (excellent for use in remote areas) and easy to store; some are even small enough to fit into a rucksack. They are usually battery powered and feature a low wattage light source of between 6 and 20 Watts (however some mains operated traps can reach 40 Watts), and consequently these traps have lower catch sizes and retention rates than Skinner or Robinson models.

Compact 20W Actinic Heath Moth Trap (240V)

* Price: £149.00 inc VAT

* Dimensions: 47 (h) x 25 (w) x 25 (d) cm

* Weight: 3kg

* Electrics: 240V mains electric

* Also available as a battery-operated unit.

Suggested books on Moths

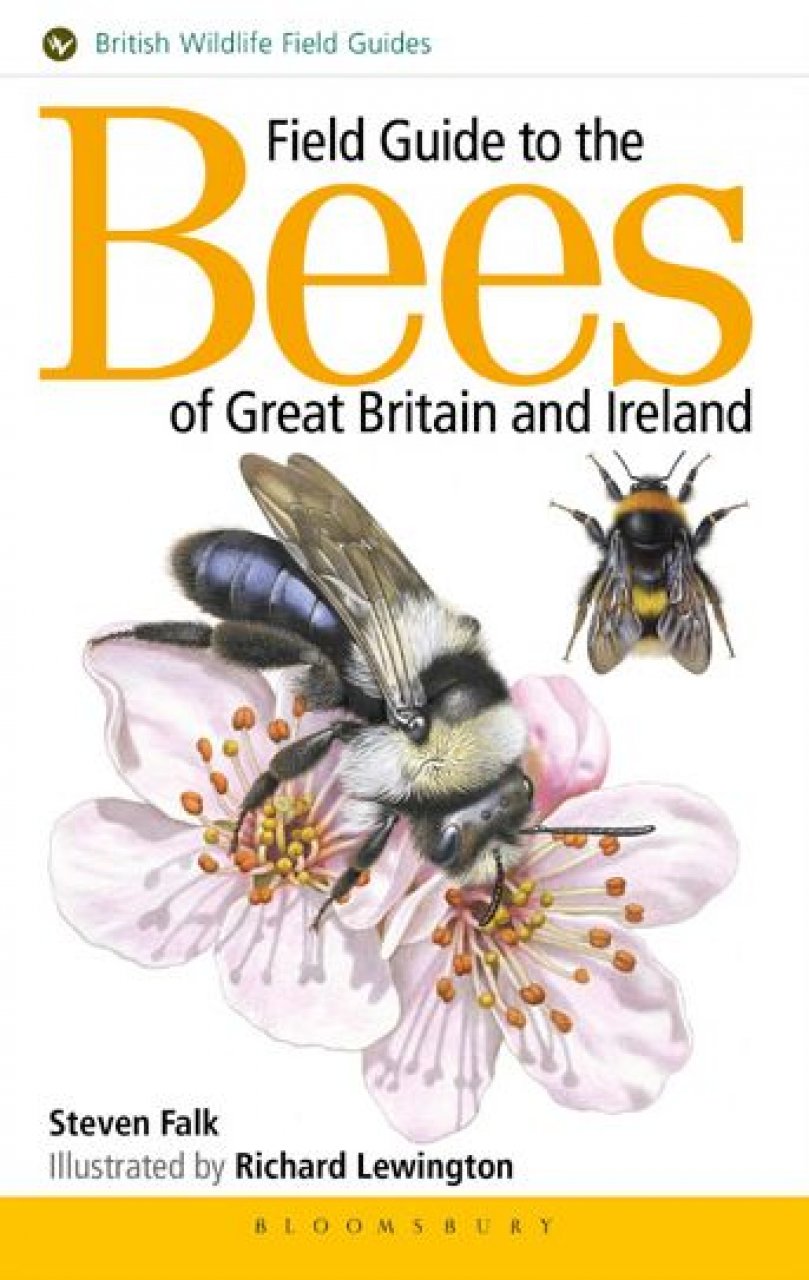

Field Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland

Paperback | Nov 2018| £27.99 £34.99

A comprehensive guide with full colour illustrations and up-to-date information on the taxonomy, ecology and distributions of the UK’s macro-moths.

Concise Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland

Paperback | Oct 2018| £13.99 £16.99

This compact guide features full colour illustrations and concise descriptions for almost all British and Irish species of macro-moths

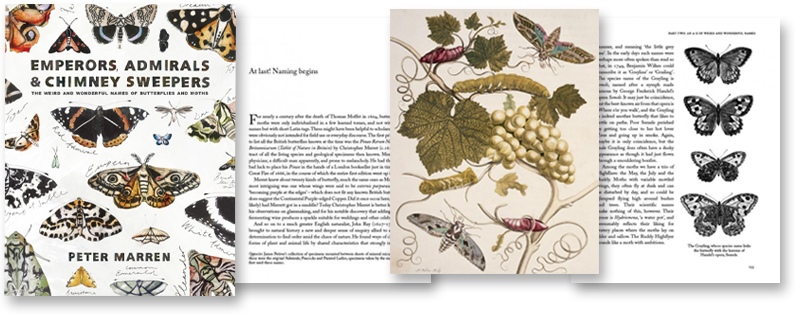

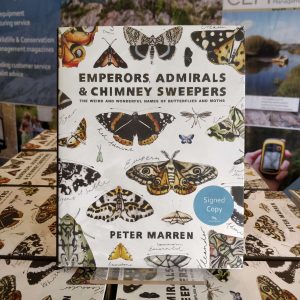

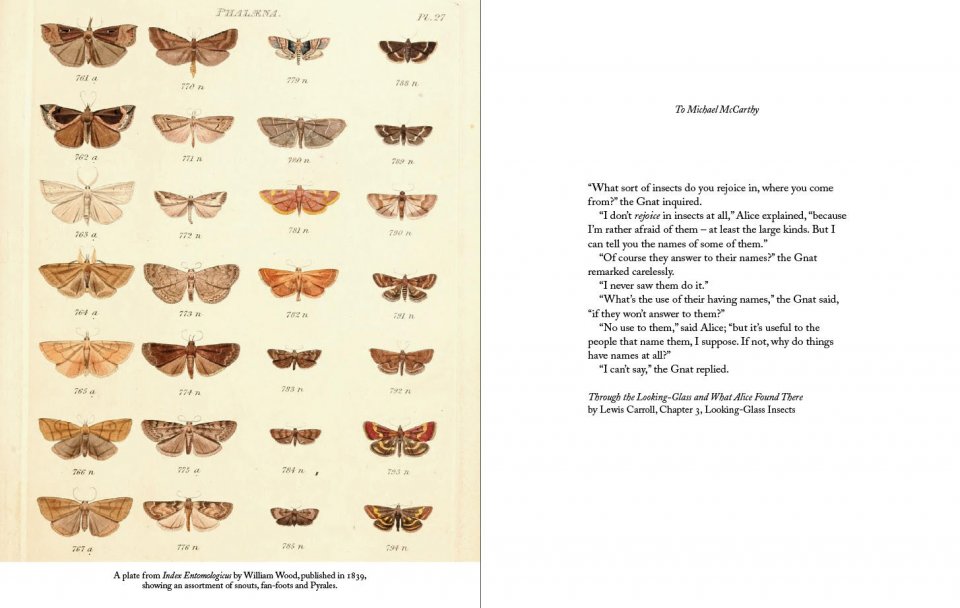

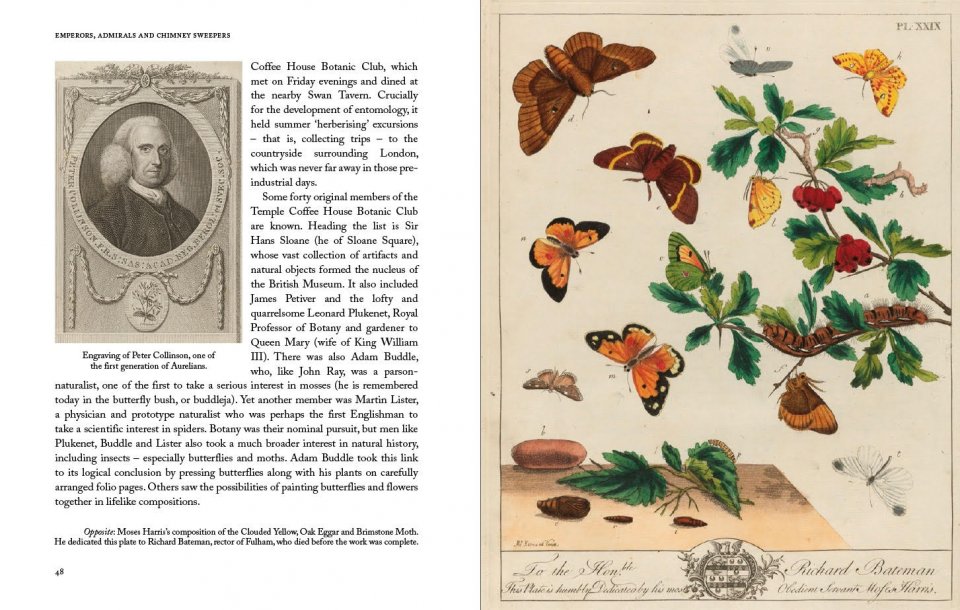

Emperors, Admirals & Chimney Sweepers | The Weird and Wonderful Names of Butterflies and Moths

Emperors, Admirals & Chimney Sweepers | The Weird and Wonderful Names of Butterflies and Moths

Hardback | May 2019| £24.99 £29.99

A beautifully written book that seeks to explore the origins and meanings of the names of our butterflies and moths.

The Moth Snowstorm | Nature and Joy

The Moth Snowstorm | Nature and Joy

Paperback | Apr 2016| £9.99

Drawing on a wealth of memorable experiences from a lifetime of watching and thinking about wildlife and natural landscapes Michael McCarthy presents a new way of looking at the world around us.

Please note that prices stated in this blog post are correct at the time of publishing and are subject to change at any time.

I’m a natural history writer (in the sense that I’ve written a lot about natural history) with a background in nature conservation in Britain. I’ve loved butterflies and moths since boyhood, and I suppose I must have realised even then that many of them have unusual names. What the hell was an eggar? Or a lutestring? Probably like most people I didn’t think too much about it – weren’t names just labels? – until, out of curiosity, I went into the name of the Red Admiral, Vanessa atalanta, and discovered a real Vanessa and a real Atalanta. And then I realised that even Latin names weren’t randomly chosen but had a particular resonance with that particular species. Names hid a whole new world of allusion, poetry and wordplay. I discovered that those who named our Lepidoptera, in English and Latin, were equally educated in the arts and the sciences. They knew their myths, and they knew about colours and designs, and they were completely fascinated. I feel a strange empathy with that vanished world.

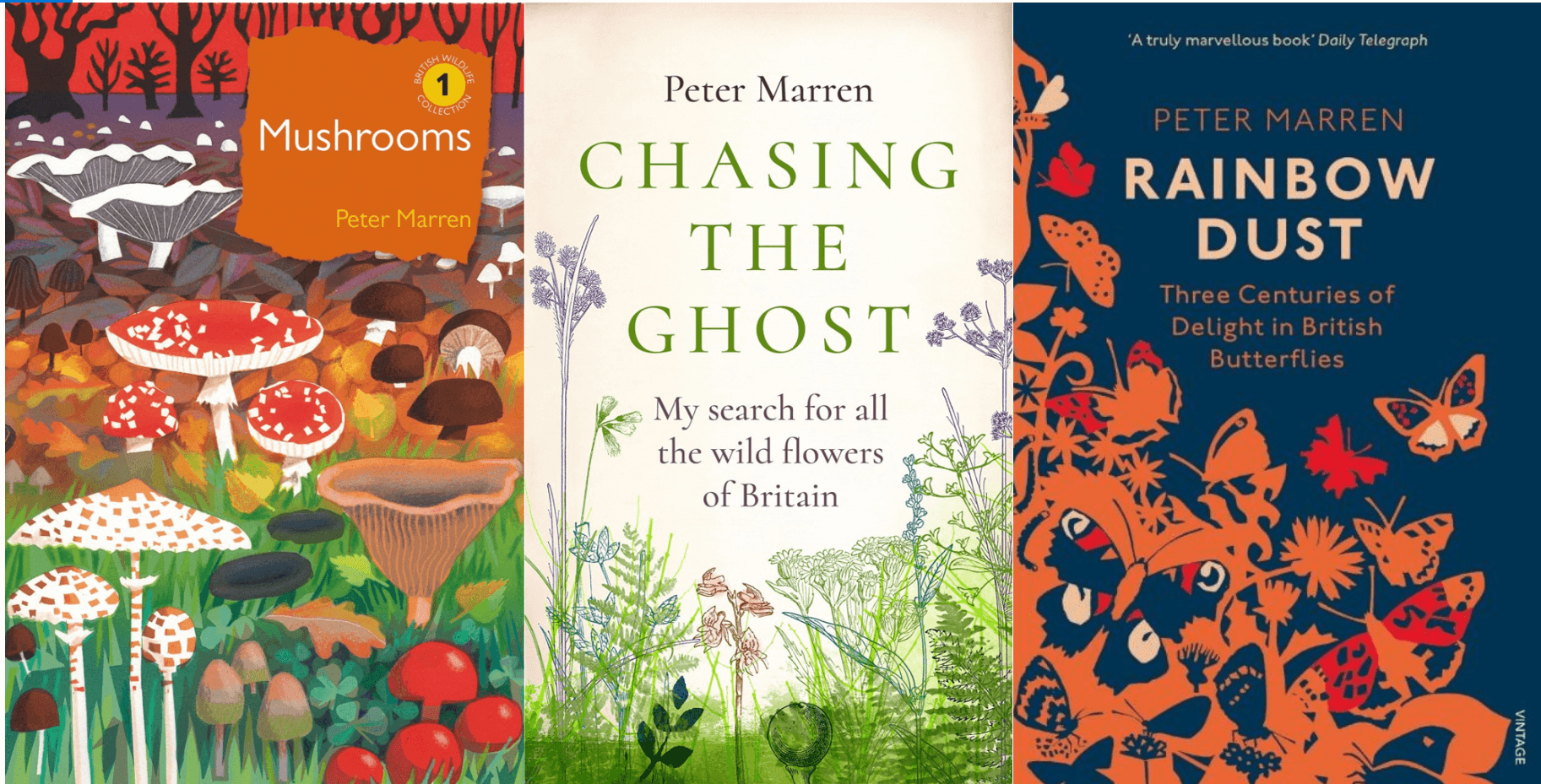

I’m a natural history writer (in the sense that I’ve written a lot about natural history) with a background in nature conservation in Britain. I’ve loved butterflies and moths since boyhood, and I suppose I must have realised even then that many of them have unusual names. What the hell was an eggar? Or a lutestring? Probably like most people I didn’t think too much about it – weren’t names just labels? – until, out of curiosity, I went into the name of the Red Admiral, Vanessa atalanta, and discovered a real Vanessa and a real Atalanta. And then I realised that even Latin names weren’t randomly chosen but had a particular resonance with that particular species. Names hid a whole new world of allusion, poetry and wordplay. I discovered that those who named our Lepidoptera, in English and Latin, were equally educated in the arts and the sciences. They knew their myths, and they knew about colours and designs, and they were completely fascinated. I feel a strange empathy with that vanished world. It started as a kind of sequel to my book Rainbow Dust, about how and why butterflies and moths inspire people. Names were confined to a single chapter in that book, but there was so much more to say, not only about the names themselves but the social ambience that spawned them: the world of Georgian London with its clubs and field excursions, its gorgeous illustrated books and the sense that nature was all the more wonderful for being 1) divinely inspired and 2) almost completely unknown.

It started as a kind of sequel to my book Rainbow Dust, about how and why butterflies and moths inspire people. Names were confined to a single chapter in that book, but there was so much more to say, not only about the names themselves but the social ambience that spawned them: the world of Georgian London with its clubs and field excursions, its gorgeous illustrated books and the sense that nature was all the more wonderful for being 1) divinely inspired and 2) almost completely unknown.

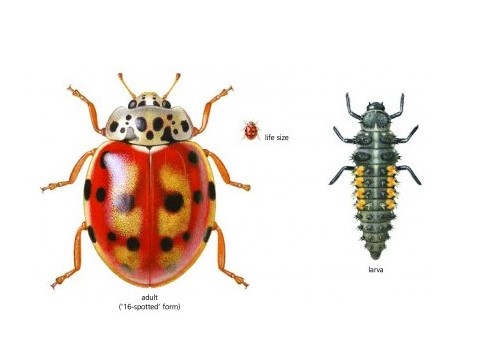

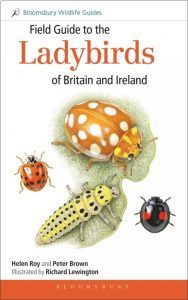

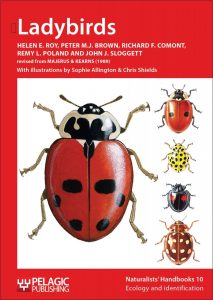

Professor Helen Roy’s research at the Biological Records Centre focuses on the effects of environmental change on insect populations and communities, and she is particularly interested in the dynamics of invasive species and their effects on native biodiversity.

Professor Helen Roy’s research at the Biological Records Centre focuses on the effects of environmental change on insect populations and communities, and she is particularly interested in the dynamics of invasive species and their effects on native biodiversity. Dr Peter Brown is an ecologist and senior lecturer in zoology at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge. His research focuses on three main areas: ladybirds, non-native species and citizen science.

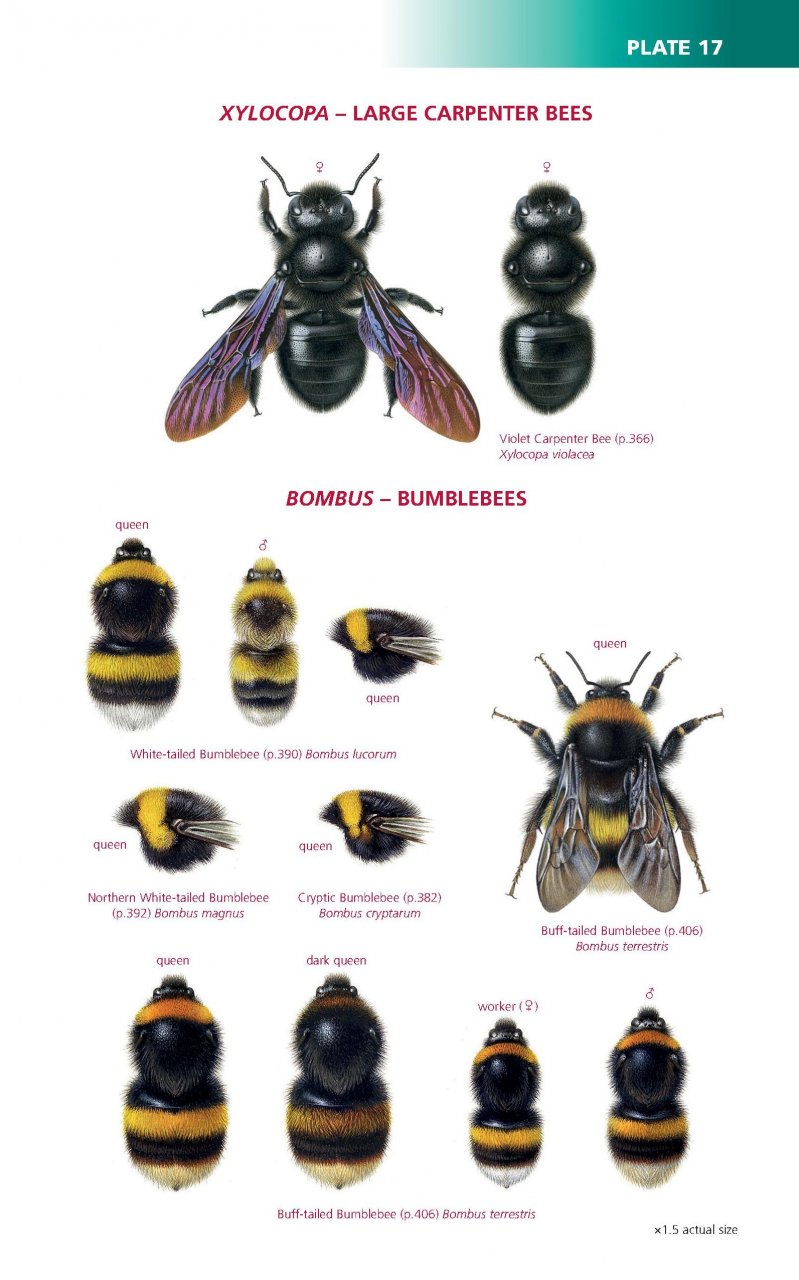

Dr Peter Brown is an ecologist and senior lecturer in zoology at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge. His research focuses on three main areas: ladybirds, non-native species and citizen science. Richard Lewington is regarded as being one of the finest wildlife illustrators. His meticulous paintings of insects and other wildlife are the mainstay of many of the modern classics of field-guide art, including the

Richard Lewington is regarded as being one of the finest wildlife illustrators. His meticulous paintings of insects and other wildlife are the mainstay of many of the modern classics of field-guide art, including the

![Tommy Karlsson, author of Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland] Tommy Karlsson, author of Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://blog.nhbs.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Tommy-Karlsson-300x284.png)

![Onychogomphus foripatus description and distribution map from Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://media.nhbs.com/jackets/jackets_resizer_large/22/224242_4.jpg)

![Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://media.nhbs.com/jackets/jackets_resizer_large/22/224242.jpg)

Dr Dino Martins is an entomologist and evolutionary biologist with a PhD in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology from Harvard University. He is also well-known in his native East Africa where he works to educate farmers about the importance of the conservation of pollinators. It is

Dr Dino Martins is an entomologist and evolutionary biologist with a PhD in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology from Harvard University. He is also well-known in his native East Africa where he works to educate farmers about the importance of the conservation of pollinators. It is