![Tommy Karlsson, author of Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland] Tommy Karlsson, author of Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://blog.nhbs.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Tommy-Karlsson-300x284.png)

Thank you very much! I am a biologist and work since 2005 at the department of Nature Conservation at the County Administrative Board of Östergötland, mainly with action plans for threatened species. I have always been interested by natural history, and as a kid I liked to collect larvae of dragonflies, stoneflies, mayflies and other limnic insects. However, my interest for imago dragonflies and identification of species started during my biology studies, about 2002-2003.

For those who may not be familiar with the natural history of Sweden, what sort of place is Östergötland in terms of biodiversity and landscape?

Östergötland is situated in south east Sweden and covers 14,500 km sq. It is situated in the boreonemoral vegetation zone and can be divided into four natural geographic regions: the southern woodlands, the plains, the archipelago, and the northern woodlands. The woodlands and the archipelago mainly consist of coniferous forests, while the plains mainly consists of intensively cultivated agricultural land. The woodlands have great numbers of lakes and mires, while the plains are very poor in water. The main part of Östergötland is lowlands, but in the southern woodlands there are considerable areas above 200 m.a.s.l. The bedrock in the county is mainly acid but in the western part of the plains there is an area of Cambro-silurian calcareous rock. During the last glaciation, calcareous material was dispersed southwards, resulting in calcareous soils in some parts of the southern woodlands with granite bedrock. As a consequence of bedrock and soils you find mainly oligotrophic and dystrophic waters in the northern woodlands, eutrophic waters in the plains, and a mix of oligotrophic, dystrophic and mesotrophic in the southern woodlands. Östergötland, along with other southeastern regions, is one of the most species-rich regions in Sweden considering invertebrates due to its relatively warm and dry summers. It is well known for its considerable areas with hollow oaks and the saprolyxic fauna and flora associated with them.

![Onychogomphus foripatus description and distribution map from Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://media.nhbs.com/jackets/jackets_resizer_large/22/224242_4.jpg)

It worked out very well since all was based on voluntarism. After getting initial information about surveying and identifying dragonflies, the participants could work quite independently. Most of the communication with the participants was made through e-mail. In addition, several activities were organized: kick-offs every spring, survey courses and excursions during summer, and reporting courses during fall. Many of the participants had no experience of surveying dragonflies before, and the fact that we managed to get so many volunteer amateurs out surveying dragonflies was one of the highlights of the project. Furthermore, the participants were a heterogenous group in terms of age and gender, and not only older men which is common in entomological contexts.

In the study you make comparisons with 10 other regions in Europe. What conclusions have you been able to draw through these comparisons?

Yes, I compare Östergötland with some other European regions where dragonfly surveys have been performed. Most of the regions have more species than Östergötland because they are situated south of Östergötland. On the other hand, Östergötland has two species which generally are missing in the other regions: Coenagrion johanssoni and Aeshna serrata. When comparing the species the regions have in common, the frequency for some species differs a lot between Östergötland and the other regions. Östergötland is distinguished by the fact that species classified as red-listed and/or decreasing in Europe occur more frequently in Östergötland than in most of the other regions. Particularly Coenagrion armatum and Leucorrhinia caudalis can be pointed out as much more common in Östergötland. Thus, Östergötland has both a national and international responsibility for these species, together with A. serrata, Aeshna viridis and Nehalennia speciosa. The reason for this is that important habitats for these species, such as bog ponds and mesotrophic lakes are naturally more common in Sweden, and that the exploitation of waters in Sweden has not been as severe as in central Europe.

![Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://media.nhbs.com/jackets/jackets_resizer_large/22/224242.jpg)

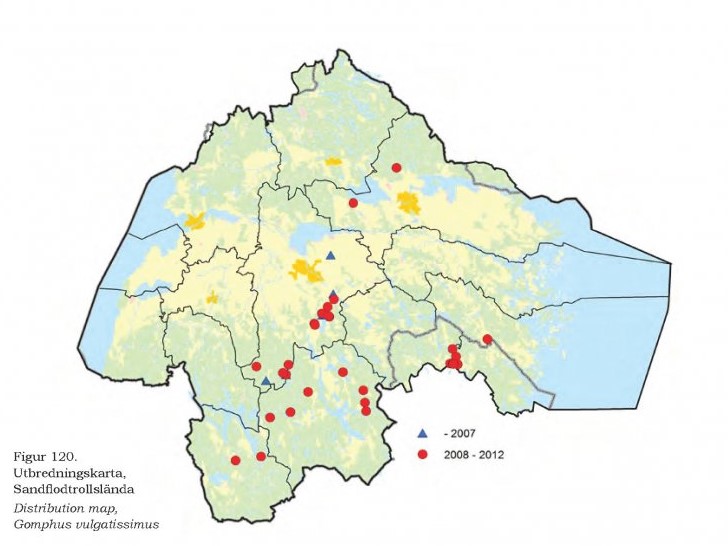

Probably because of global warming there is an ongoing change in the European dragonfly fauna where several southern species have expanded rapidly northwards and some northern species have retreated. In Östergötland the establishment of Lestes virens and Ischnura pumilio has been documented during the survey. L. virens was observed for the first time in the county in 2005 and, during the period 2008-2012, was found at several new localities every year. I. pumilio was first noted for the Östergötland in 2012.

And what is next for you and for the Östergötlands Entomological Society?

This year I have got the assignment to co-ordinate Sweden’s monitoring of the dragonflies species listed in the EU’s habitat directive. It will be very nice to work professionally with dragonflies and I have learned a lot about these species and dragonfly monitoring during the survey in Östergötland. I started this work last week with a field study of Ophiogomphus cecilia, a species only occurring in some few unregulated rivers in the very far north of Sweden. Concerning the Entomological Society in Östergötland, we have discussed the possibility of starting up another voluntary survey of some other easy identified insect group, e.g. shield bugs or grasshoppers, but nothing is ready to start yet.

Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland] is available now from NHBS