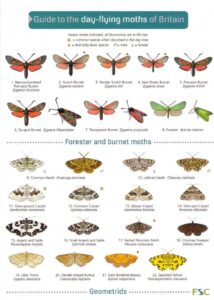

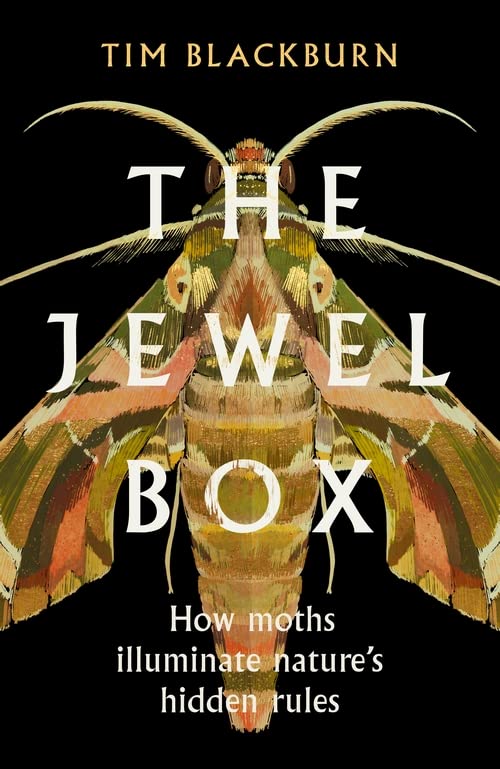

Interwoven throughout with tales of his experiences moth trapping on his London rooftop and in the Devon countryside, The Jewel Box by Tim Blackburn introduces us to a range of ecological theories and explains some of the where, why and hows that anyone curious about the natural world might tend to ponder upon. Beautifully and engagingly written, it manages to be both an ode to both the moths themselves and the activity of moth trapping, as well as a wider ranging exploration of the relationships between humans, other species and habitats.

Interwoven throughout with tales of his experiences moth trapping on his London rooftop and in the Devon countryside, The Jewel Box by Tim Blackburn introduces us to a range of ecological theories and explains some of the where, why and hows that anyone curious about the natural world might tend to ponder upon. Beautifully and engagingly written, it manages to be both an ode to both the moths themselves and the activity of moth trapping, as well as a wider ranging exploration of the relationships between humans, other species and habitats.

Professor Tim Blackburn is a scientist with thirty years of experience studying questions about the distribution, abundance and diversity of species in ecological assemblages. He is currently a Professor of Invasion Biology at University College London, where his work focuses on alien species. Before that, he was the Director of the Institute of Zoology, the research arm of the Zoological Society of London.

Professor Tim Blackburn is a scientist with thirty years of experience studying questions about the distribution, abundance and diversity of species in ecological assemblages. He is currently a Professor of Invasion Biology at University College London, where his work focuses on alien species. Before that, he was the Director of the Institute of Zoology, the research arm of the Zoological Society of London.

In this Q&A we chatted with Tim about The Jewel Box as well as about moths in the UK, the things we still have to learn about them, and the species that he’s hoping to see in the flesh.

What struck me most about your book was how you manage to write about complex ecological theories in a very accessible way, while at the same time conveying your very personal admiration and fascination for these insects. What was it that convinced you that this book in particular needed writing?

For a few years now I’d wanted to write a book that presented the natural world in the way that ecological scientists tend to think about it. There is a lot of very fine writing about nature, but most of it is more natural history than science, or is very much focused on a specific organism or location. While The Jewel Box does use moths to illuminate and illustrate the rules that we (ecological scientists) think underpin how nature works, it is very much about those rules, rather than the moths themselves. I’m very happy to hear that you thought I explained the science in an accessible way – that was my fundamental goal.

Within the UK, we have a rich history of recording and studying moths. Where do you think are the big gaps currently in the research? Are there things about moths that we still know little about?

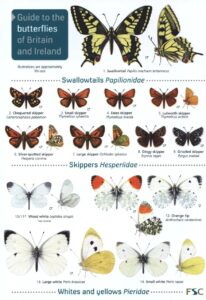

There are still lots of gaps in our knowledge of UK moths – hardly surprising given that we have 2,500 or so species here. For some, we still don’t know their natural food plant. For others, we don’t know if they still exist here. In this latter regard, it seems incredible to me that we are still arguing about the scale of insect declines in the UK, and what the causes of those declines are. We think moth numbers have probably dropped by 30% since 1970, but that information is only available for the commoner species of larger moths, and may be biased in various ways. While we have a rich history of moth recording, and some good data for moth population changes, we could really do with more.

Why do you think it can be so addictive to observe, identify and list the species that we find, whether it’s birds, plants or moths?

I don’t know! For me, it’s pretty much a hard-wired instinct. My mother says I was pointing at birds before I could talk. I’ve been a birder all my life. More generally, there is something deeply satisfying about observing and identifying species – a series of puzzles to work out. Yet unlike most puzzles, the solution is not a product of the human mind, but something more profound. It’s the start of an exploration into understanding millions of years of evolution and ecology. I love a cryptic crossword, but identifying moths gives me so much more joy.

As someone who was trapping before, during and after the Covid restrictions, did you observe any significant differences in the numbers or species of moths that were attracted to your trap during the periods of lockdown?

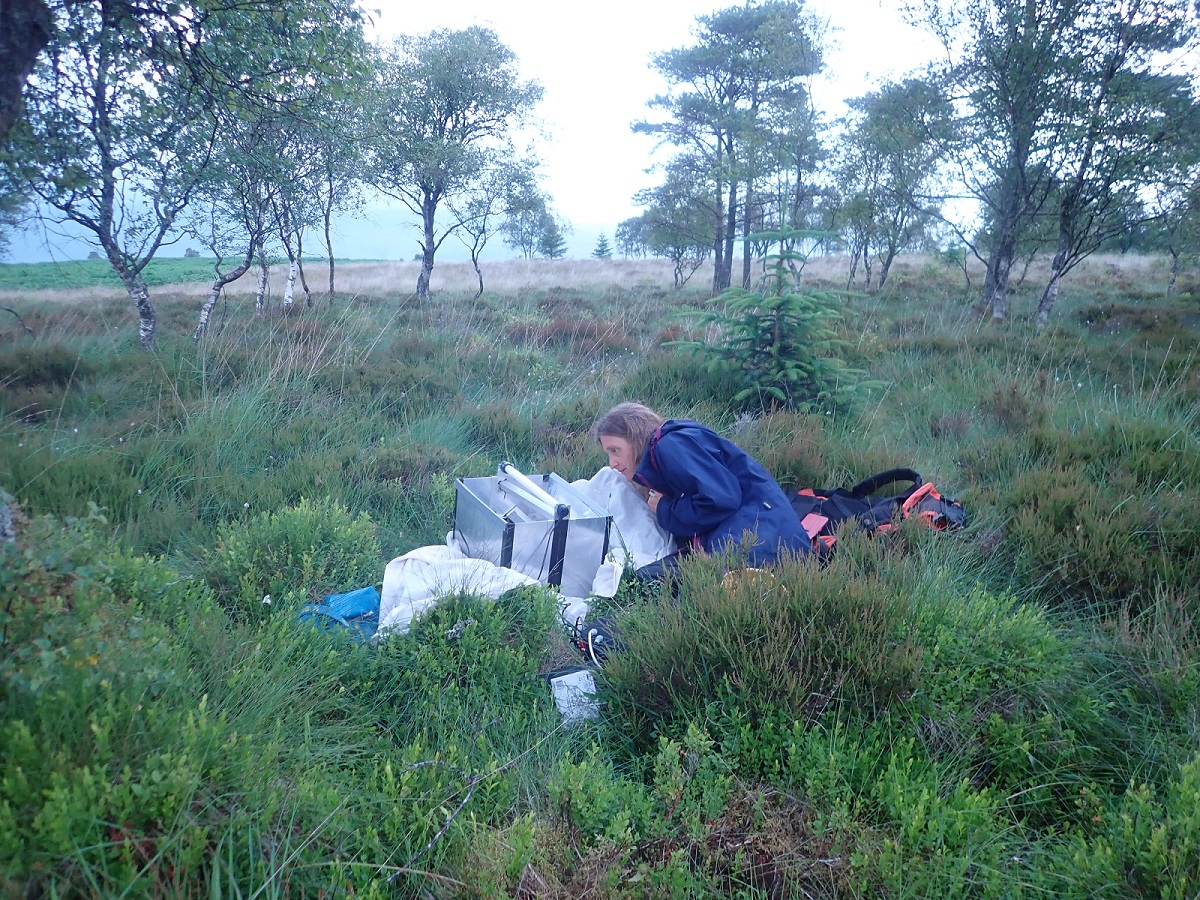

I wouldn’t say I noticed obvious differences due to lockdowns, although the first lockdown period itself was a very productive one for my moth trap. That was because I was in the Devon countryside when lockdown happened, rather than my upstairs London flat. The countryside is so much better for moths (numbers of species and individuals) than the city, and that spring was notably warm and sunny, which the moths loved. The 2020 lockdown was my most intensive period of trapping to date.

We are generally well informed about planting wildflowers for pollinators such as bees and butterflies and providing food for our garden birds. But what can we do to encourage moths?

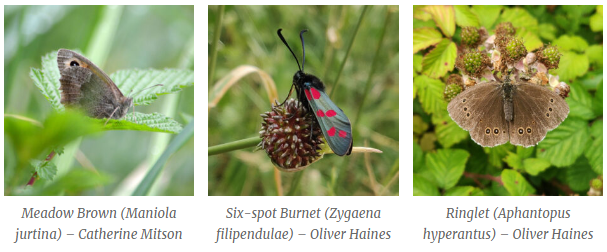

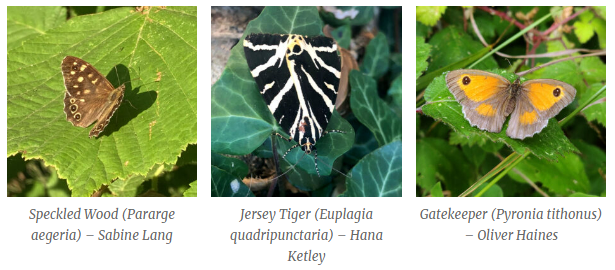

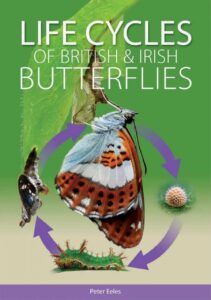

The same really! Butterflies are just showy, diurnal moths. Moths are as good pollinators as bees, and like flowers and pollen just as much. So anything you do for the butterflies and bees will likely help the moths too. You just won’t see the impact as obviously, because most of the moths are using your garden while you’re sleeping.

Are there any species that you’ve yet to trap but are on your mothing ‘bucket list’ so to speak?

In The Jewel Box, I spoke about dreaming of catching a Death’s-head Hawk-moth, one of the largest and most iconic British moth species. Last October, I opened my moth trap on Blakeney Point in Norfolk to see that that dream had come true. It’s a moment that will stay with me forever. Now, Oleander Hawk-moth– the species that inspired the book’s cover – would be the dream, albeit even less likely than catching the Death’s-head.

Finally, what’s in store for you next? Do you have plans for further books?

I’m mulling on the next book, but still enjoying all that’s new and interesting in my life as a result of publishing The Jewel Box. But watch this space…

The Jewel Box by Tim Blackburn was published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in June 2023 and is available from nhbs.com.

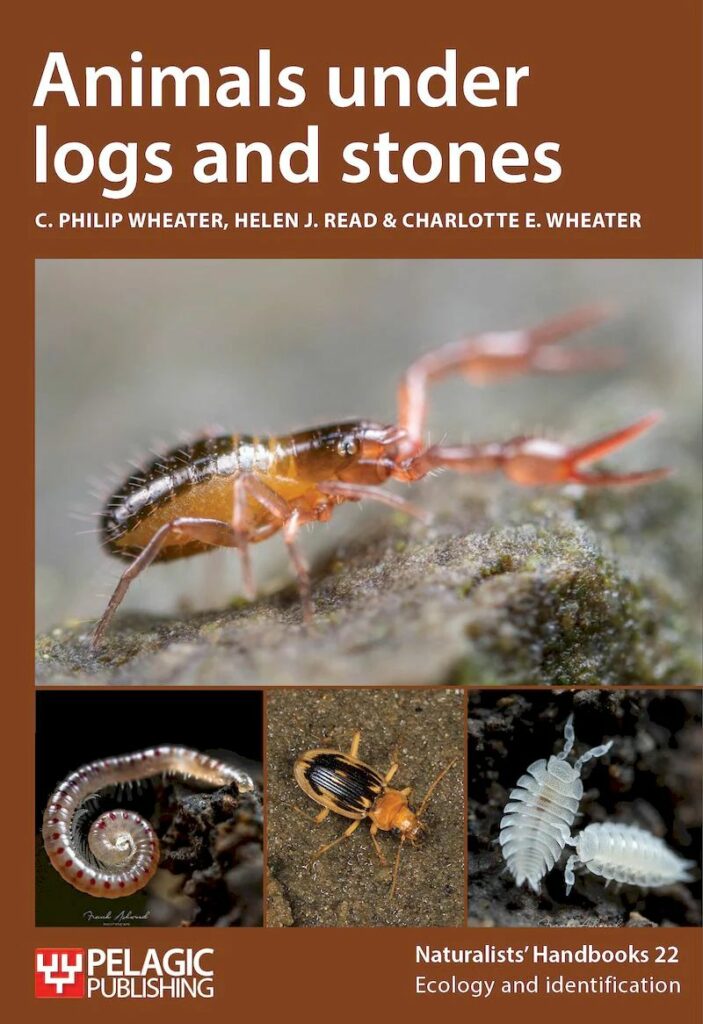

Helen Read is a Conservation Officer for the City of London Corporation based at Burnham Beeches, a post held for over 30 years. She has written numerous books and papers on a variety of subjects, the majority being on the management of veteran trees and topics relating to invertebrates. She has also been an active committee member in various invertebrate societies.

Helen Read is a Conservation Officer for the City of London Corporation based at Burnham Beeches, a post held for over 30 years. She has written numerous books and papers on a variety of subjects, the majority being on the management of veteran trees and topics relating to invertebrates. She has also been an active committee member in various invertebrate societies.

I’m a big fan of all insects (and other invertebrates) and generally, as long as I’m learning new things, I’m happy. However, with moths, I love that you don’t need a microscope to enjoy their beautiful variety and a light trap means many species can be enjoyed relatively easily. It’s hard not to be impressed by the stature of a Poplar Hawk-moth or the delicacy of a White Plume Moth. They are also great insects to share with others; excellent ambassadors for our often-overlooked smaller fauna.

I’m a big fan of all insects (and other invertebrates) and generally, as long as I’m learning new things, I’m happy. However, with moths, I love that you don’t need a microscope to enjoy their beautiful variety and a light trap means many species can be enjoyed relatively easily. It’s hard not to be impressed by the stature of a Poplar Hawk-moth or the delicacy of a White Plume Moth. They are also great insects to share with others; excellent ambassadors for our often-overlooked smaller fauna. Yes, I think so, particularly in archives with accompanying notes and diaries. Just as contemporary recorders have slightly different motivations; for example seeing as many species as possible or understanding the moths of a particular area well, so did collectors from the past. The details that are written on the labels, the handwriting, the comments in notebooks all hint at the personality of the characters involved. I’m not sure our modern legacy of spreadsheets and digital photo archives provide the same back story. Of course in many cases – a bit like social media feeds – only the significant finds and achievements get documented for prosperity. Failures are brushed aside and conveniently forgotten.

Yes, I think so, particularly in archives with accompanying notes and diaries. Just as contemporary recorders have slightly different motivations; for example seeing as many species as possible or understanding the moths of a particular area well, so did collectors from the past. The details that are written on the labels, the handwriting, the comments in notebooks all hint at the personality of the characters involved. I’m not sure our modern legacy of spreadsheets and digital photo archives provide the same back story. Of course in many cases – a bit like social media feeds – only the significant finds and achievements get documented for prosperity. Failures are brushed aside and conveniently forgotten.