Climate change

The US Supreme Court has limited the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) ability to curb power plant emissions, impacting America’s attempts to fight climate change. The Supreme Court ruled that the Clean Air Act does not give the EPA broad authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. The Biden administration plans to combat climate change by cutting the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions in half by the end of the decade and aiming for an emissions-free power sector by 2035. Now, the decision to curb power plant emissions must be taken by Congress itself, or “an agency acting pursuant to a clear delegation from that representative body.”

In other climate news, both Spain and Portugal are suffering the driest climate for at least 1,200 years, according to new research. Azores highs, high-pressure systems off the coast that blocks wet weather fronts in winter, have dramatically increased since 1980, pushing wet weather northwards. This is having severe implications for both food production and tourism. This change has been conclusively linked to increased anthropogenic emissions.

Scientists have warned Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) against watering down EU deforestation laws. Last week, a draft regulation was rewritten to define ‘forest degradation’ as the replacement of primary forests by plantations or other wooded land. As primary forests account for only 3.1m hectares of 159m hectares of overall forest, this definition would severely limit the law’s reach to only 2% of the total forest area. A letter from more than 50 scientists has stated that any exclusion of forest degradation from the law would undermine the EU’s desire for Europe to “become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050.”

Conservation

Bird flu has been confirmed at the UK’s only breeding colony of roseate terns in Northumberland. This “new virulent” form of bird flu is having a devastating impact on a number of wild bird species, with hundreds of seabirds found dead on Coquet Island. There are now calls for the government to develop and implement a national response plan for bird flu in wild birds, including clarity for collecting dead birds and a long-term plan for future threats. This disease is affecting all four species of tern on the island, as well as eider ducks, black-headed gulls and large gulls. The island is also home to nesting puffins but, so far, no puffin deaths have been recorded.

A £4.1m scheme has been revealed to improve wildlife habitats and alleviate flooding alongside roads in Stafford. The Stafford Brooks Project will target 25 locations near local rivers and streams to address the environmental impact of roads. Space will be created for wildflowers, trees and wildlife in areas where habitats have been impacted by activities from previous road building. New wetlands and reed beds are also being designed to help filter polluted run-off from roads, which can significantly impact river health.

A 3-metre-high weir in Cumbria is being demolished as part of a national push to allow fish and invertebrates to move more freely along the UK’s rivers. The River Kent is an internationally important site of special scientific interest as its home to species such as white-clawed crayfish and freshwater pearl mussels. The removal of Bowston weir will help to renaturalise part of the River Kent by improving biodiversity, restoring migration routes and reducing flooding risks for local residents.

The greater glider is now considered endangered due to population declines caused by logging, bushfires and global heating. This cat-sized marsupial has slipped from vulnerable to endangered on the federal government of Australia’s list of threatened species. There are calls from experts and conservationists to back this move with urgent action to preserve habitats and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Research

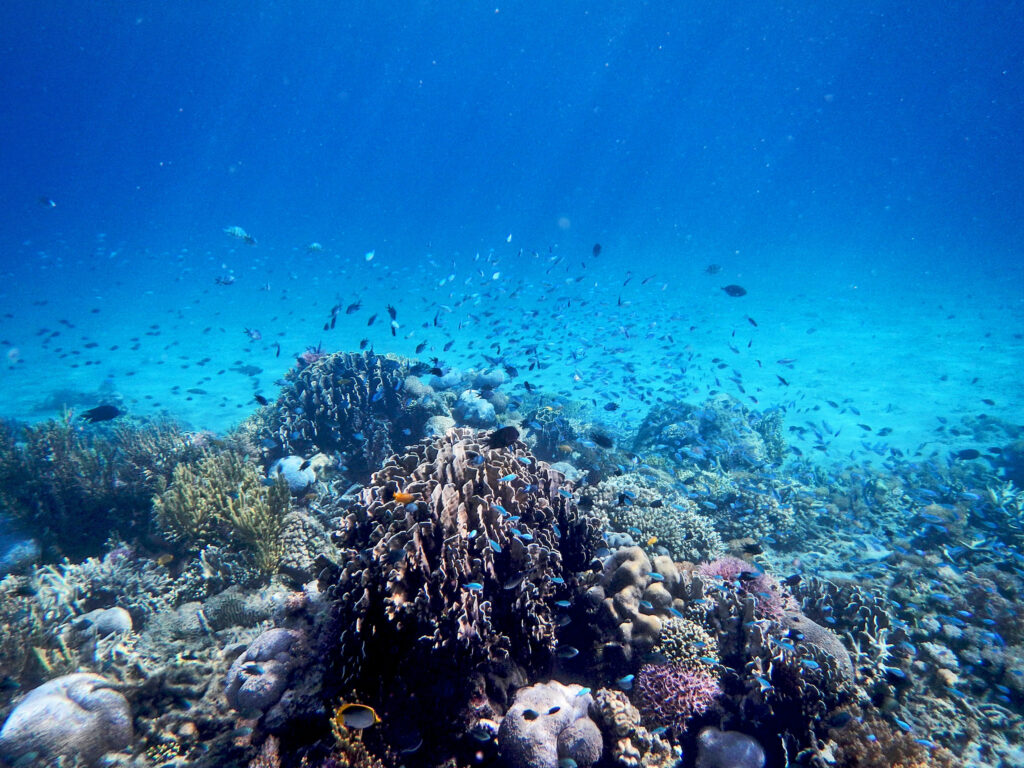

Researchers are satellite-tracking whale sharks to explore the factors influencing their behaviour in the coastal waters of the Panamanian Pacific, including migratory and feeding behaviours. Rhincodon typus is vulnerable to population declines due to their slow maturation and they face a number of threats from humans, including entanglement in fishing nets and boat strikes. This study has shown that whale sharks spend more than 77% of their time in areas without any protection, indicating that conservation measures should go beyond the creation of local marine protected areas.

A new study, part-funded by The Mammal Society, has revealed the presence of plastic consumption in small mammals. More than 261 faecal samples were analysed to assess the exposure of seven terrestrial UK mammals to plastics. Four species, the European hedgehog, wood mouse, field vole and brown rat all had plastic polymers detected within their faecal samples. This ingestion was shown to occur across species of differing dietary habits and locations, confirming that plastic consumption is a widespread issue.

New Discoveries

A new giant water lily species has just been discovered, despite being in the archives of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, for 177 years. Now holding the record as the world’s largest water lily, with its leaves growing more than 3m wide, the Victoria boliviana grows in a single water basin in part of the Amazon river system in Bolivia. It was long suspected to be different from the two other known giant species, V. amazonica and V. cruziana, but it was only when Kew grew all three side-by-side under exactly the same conditions that they could clearly see V. boliviana was totally different.

Policy

Singapore strengthened a law on Monday 4th July to stamp out wildlife trafficking, with stiffer penalties for those found guilty. The changes to the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act include tripling the maximum jail term for individuals from two to six years and increasing the maximum fine from $50,000 (~£29,550) per species to $100,000 (~£59,100) per specimen. Companies involved in the trafficking of endangered species will also face higher fines and prison sentences, according to the Senior Minister of State for National Development, Tan Kiat How.