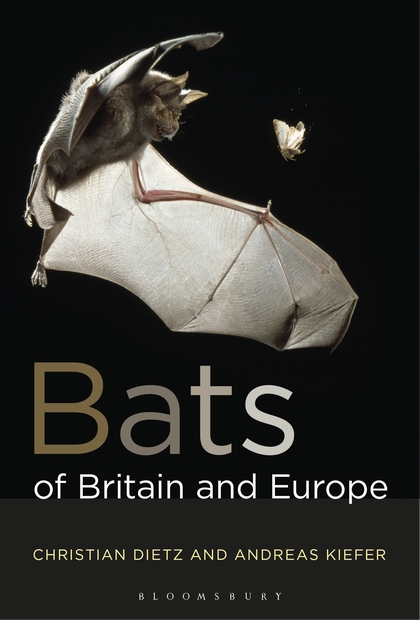

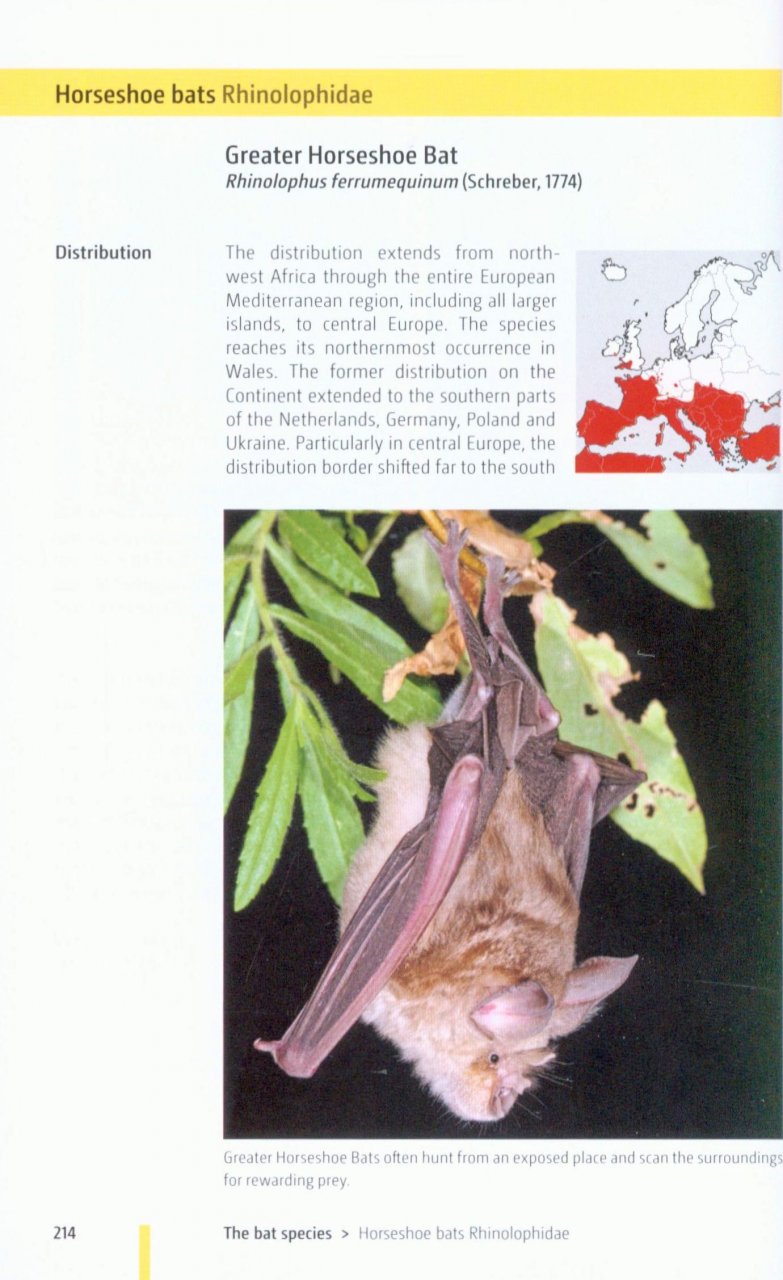

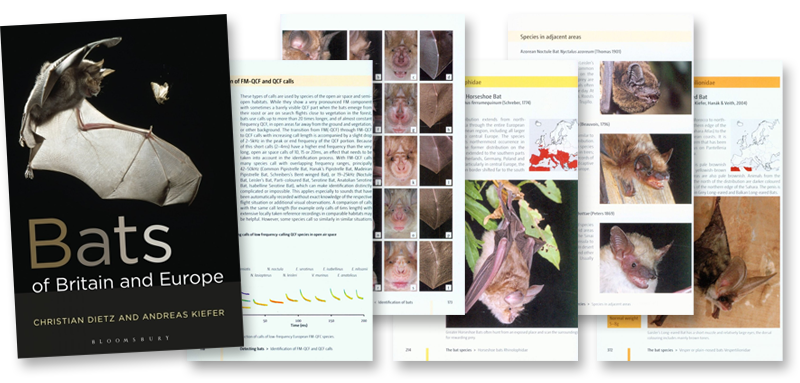

Bats of Britain and Europe is a new field guide highlighting the remarkable diversity of bat species regularly occurring in Europe. 45 species are described in detail, the pages are full of hundreds of colour photos of bats, and illustrative diagrams and tables, and there is substantial information on bat biology and ecology, tracking and detecting, and identification.

As authors Christian Dietz (long-established teacher, author and bat expert) and Andreas Kiefer (Research Associate at the University of Trier, Germany) say in the Foreword, this book represents the achievement of their “dream of continuing the field guide that introduced us both to bats” – Schober & Grimmberger 1987 /1998.

What is your background in studying and working with bats, and what makes them special for you?

Christian: I am working as a consultant in impact assessment studies mainly focused on bats and as a scientist in bat research. Bats are so special for me since they have evolved so many special adaptations to their nightly way of life and developed such a high biodiversity.

Andreas: I am a researcher in bat ecology and conservation. The diversity of bats is so big and in most species we are just barely scratching the surface on understanding them. And we need to know which species live where and why, otherwise conservation cannot be successful.

What was your first experience of seeing a bat in the wild?

Andreas: I started very late. When I was 20 I helped counting hibernating bats in slate mines, only half a year later I had my first own project. I searched for summer roosts of greater horseshoe bats in my home region but I found only grey long-eared bats. Up to now long-eareds are my favourite study objects.

Christian: As a child I found a brown long-eared bat injured by the neighbour’s cat and tried to care for it. Later I became fascinated with searching their roosts and practical conservation of hibernacula.

What areas of bat research are you currently focusing on?

Christian: As a consultant I am very interested in mitigation and monitoring of populations, and scientifically I am mostly engaged in studying the biodiversity and cryptic species in the Middle East and the Caucasus. Knowledge about the taxonomy and distribution of species is the important base for future conservation work.

Andreas: At the moment I am a researcher at Trier University. In my small bat group we currently work on the impact on wind energy on bat populations, the ecology and conservation of the Sardinian long-eared bat, and new methods for monitoring bat populations.

How are the British and European bat populations doing at the moment?

Andreas: Most of our bats species do fine, but we have signals that the grey long-eared bat is declining not only in Germany. The situation of Mehely’s horseshoe bat is more dramatic when you see it in a European context. Another species, the Sardinian long-eared bat which is endemic for Sardinia has fewer than 400 specimens left. Maybe this species will go extinct in the next years. Other species expand their range and come more to the North.

Christian: Some species like the pipistrelle bat do fine and are common and widespread, and even some rare bats like the lesser horseshoe bat seem to recover from former population crashes and slowly recolonise parts of their lost distribution. On the other hand some species still decline and may even face local extinction of populations. Examples are the grey long-eared bat and Mehely’s horseshoe bat, both specialists for preying on large moths in mosaic-like open habitats with grasslands, orchards and hedges. While the grey long-eared bat is still widely distributed, and the observed negative population trends and local extinctions still do not threaten the species as a whole, the situation with Mehely’s horseshoe bat is much more dramatic. It has already lost big parts of its European distribution and become extinct in some countries, while remaining populations are scattered and isolated. I am much afraid the species will become extinct since I have seen it disappearing in parts of Bulgaria already where I used to study it a decade ago.

If you could implement any policy change that you think would be of benefit to bats, what would it be?

Christian: Since the establishment of the European Natura 2000 network, bats get considerable protection and are taken into consideration in impact assessment and mitigation. However the implementation of these laws differs extremely between countries, and especially in the eastern parts of Europe nature protection is still difficult. There, changes in agriculture and massive habitat loss threaten some of the largest bat populations in Europe – on the other hand very expensive and sometimes ineffective compensation measures are done in western European countries. I think it would help a lot to concentrate some money from compensation to protect wonderful habitats and bats in Eastern Europe.

Andreas: Of course we need more money and projects for bat conservation, especially in Eastern Europe. And we need more sensitivity for useless compensations in Western Europe. But mainly we need a change in European agriculture politics. A better support for EU-subsidies for organic farming, less pesticides and a stop of land consumption would be helpful for bats and nature conservation overall.

The new book is a field guide to the 45 species of bat of Britain and Europe – who is the book aimed at, and what unique information will it provide for the reader?

Andreas: We hope that it is useful for professionals and beginners. For the first time, we give an overview to all European species and we show a key for the species identification of bat hairs from droppings.

Christian: We tried to give an up-to-date overview to the fascinating biodiversity of European bats and to give many ideas for practical conservation work.

You include newly described species – what can you tell us about these?

Christian: Bat taxonomy has seen big changes in the last decades, the biodiversity of European species has been much underestimated. We studied all newly discovered species in Europe from the Iberian Peninsula to Anatolia and on islands like Sardinia and Crete.

Andreas: Many new bat species had been identified in the past two decades, mainly with the help of DNA-sequencing. We tried to cover Europe and neighbouring areas and all European islands in the Mediterranean Sea.

If somebody is curious about studying bats, what advice would you give them to get started – apart from buying a copy of your book!?

Andreas: Join your local bat group! These people know what they do and they are happy when new bat friends will help them. Nothing is better than learning from experts and Britain has a lot of them.

Christian: Great Britain is famous for its many NGOs and local bat groups – so the best is to make contact to people being already engaged in bat research and conservation – they will help you.

Buy a copy of Bats of Britain and Europe

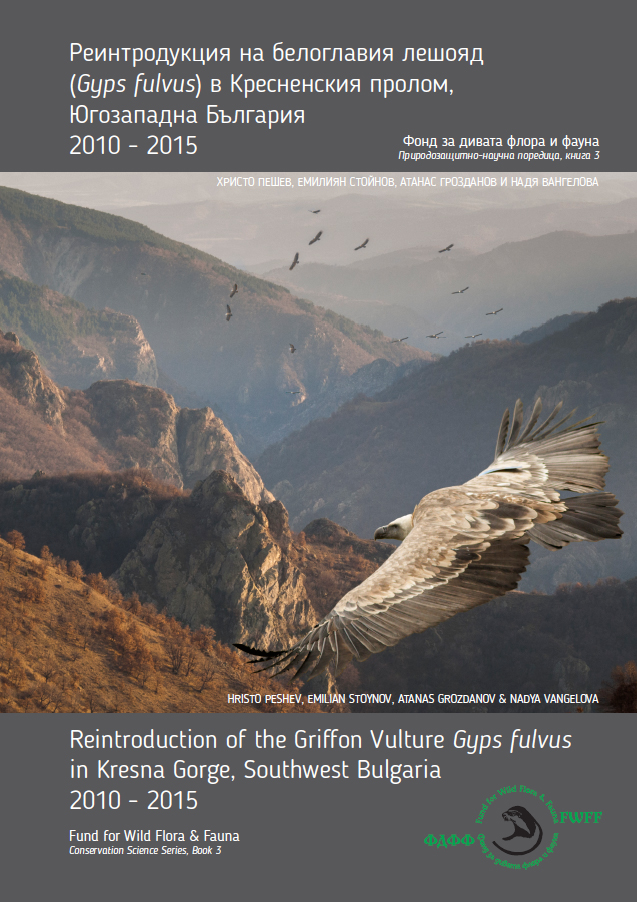

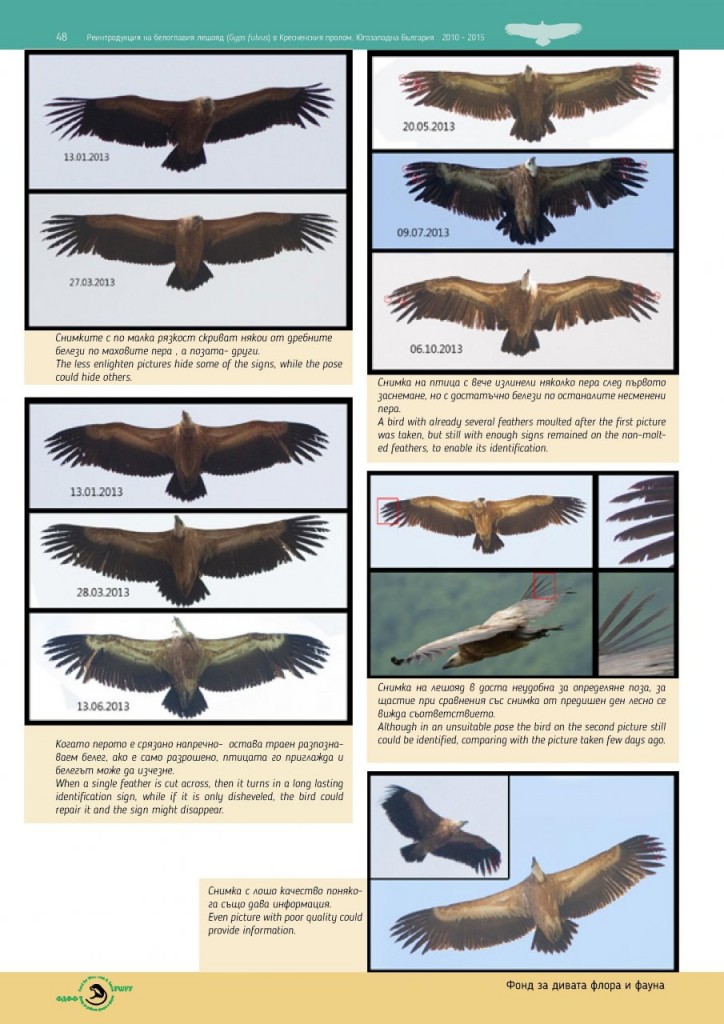

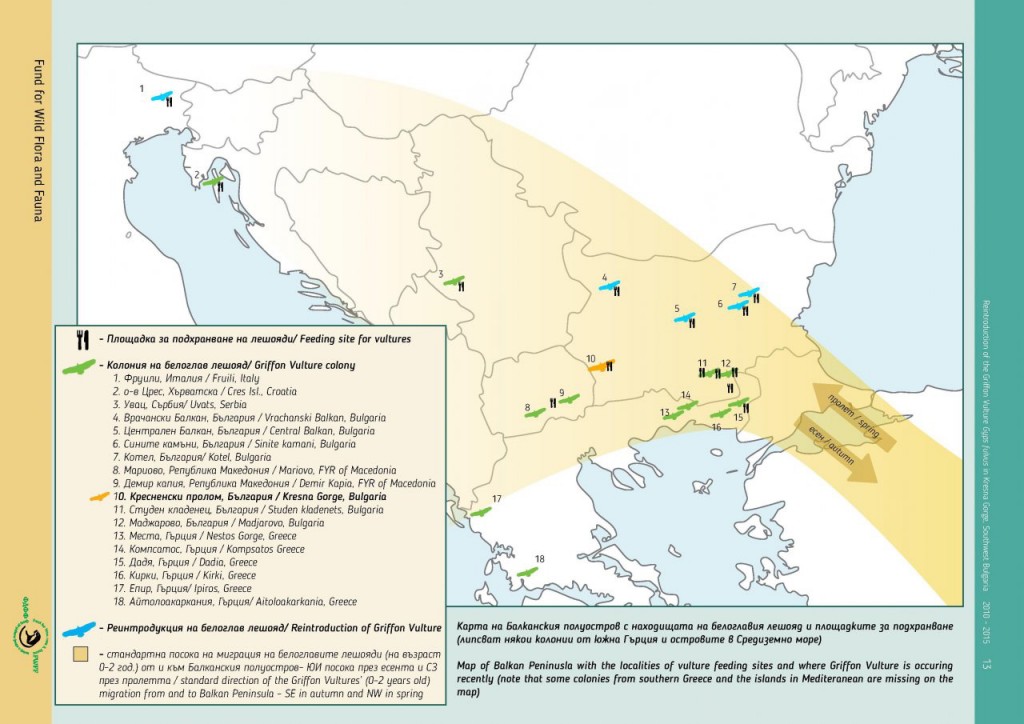

Emilian Stoynov and colleagues created the

Emilian Stoynov and colleagues created the

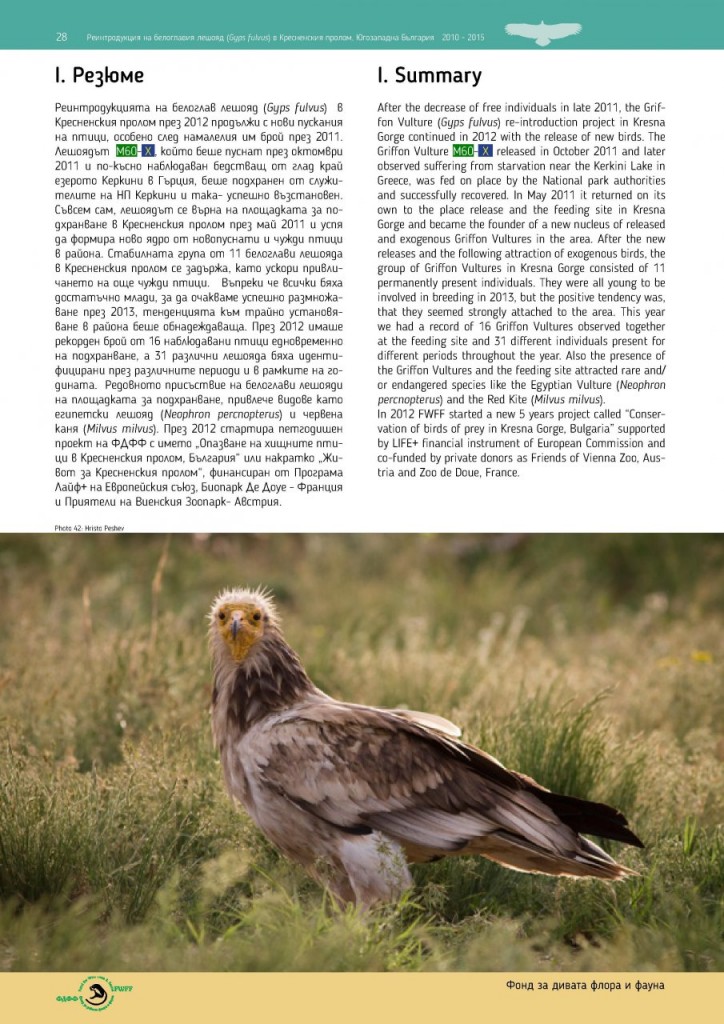

![Reintroduction of Griffon Vulture Gyps fulvus in Kresna Gorge, Southwest Bulgaria 2010-2015 [English / Bulgarian] Reintroduction of Griffon Vulture Gyps fulvus in Kresna Gorge, Southwest Bulgaria 2010-2015 [English / Bulgarian]](https://blog.nhbs.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/vultures-internal.png)

![Tommy Karlsson, author of Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland] Tommy Karlsson, author of Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://blog.nhbs.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Tommy-Karlsson-300x284.png)

![Onychogomphus foripatus description and distribution map from Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://media.nhbs.com/jackets/jackets_resizer_large/22/224242_4.jpg)

![Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://media.nhbs.com/jackets/jackets_resizer_large/22/224242.jpg)

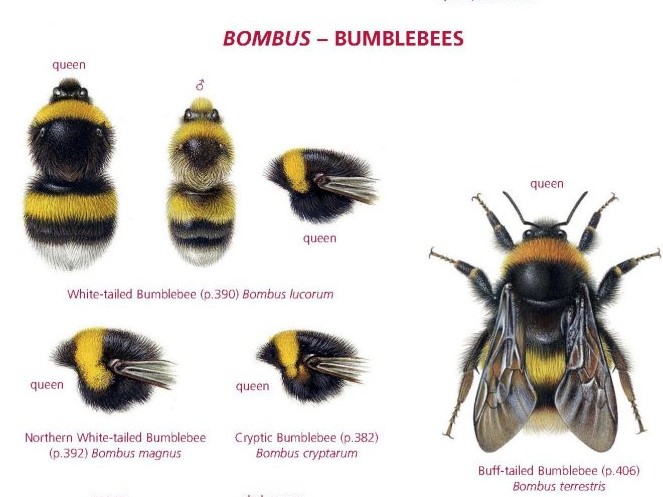

Dr Dino Martins is an entomologist and evolutionary biologist with a PhD in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology from Harvard University. He is also well-known in his native East Africa where he works to educate farmers about the importance of the conservation of pollinators. It is

Dr Dino Martins is an entomologist and evolutionary biologist with a PhD in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology from Harvard University. He is also well-known in his native East Africa where he works to educate farmers about the importance of the conservation of pollinators. It is