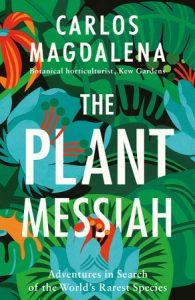

Carlos Magdalena is a botanical horticulturist at Kew Gardens, famous for his pioneering work with waterlilies and his never-tiring efforts to save some of the world’s rarest species from extinction. In his book, The Plant Messiah, Carlos shares stories of his travels and his work at Kew and, in doing so, opens our eyes to the delicate wonder of plants and the perils that many of them are now facing.

Carlos Magdalena is a botanical horticulturist at Kew Gardens, famous for his pioneering work with waterlilies and his never-tiring efforts to save some of the world’s rarest species from extinction. In his book, The Plant Messiah, Carlos shares stories of his travels and his work at Kew and, in doing so, opens our eyes to the delicate wonder of plants and the perils that many of them are now facing.

We recently caught up with Carlos to chat about plant conservation, his views on extinction and lots more.

In your book you describe your trips to some incredible places – most of which have resulted in the collection of valuable herbarium specimens and seeds for growing or storage. Where does the impetus for these projects come from? Do you get to choose the species and/or projects that you work on or are these assigned to you?

In your book you describe your trips to some incredible places – most of which have resulted in the collection of valuable herbarium specimens and seeds for growing or storage. Where does the impetus for these projects come from? Do you get to choose the species and/or projects that you work on or are these assigned to you?

They can happen for various reasons. Sometimes, they are assigned to me, like the projects in Peru and Bolivia: there is a need for a horticulturist capable of speaking Spanish, with experience in propagation of tropical plants and therefore, they contact me and from there we start the ball rolling. However, there is always the personal interest, though this works in an indirect way. Because I have been interested for years in tropical waterlilies, especially those from Australia, I had built up masses of knowledge, contacts and experience and therefore one day, someone needs someone with those skills and they want you to join in their projects. My endeavours in Mauritius started when seeds were set in a Ramosmania plant in a glasshouse in London. After this happened, there was a need to bring back this species to the island. Since this was a very genuine reason that could be solved at a very low cost, funding was allocated soon to travel and then, any time I go, I return with many more species that need working on to secure them ex-situ so you establish a working relationship with the country. There is so much work to be done that at the end of the day, money and time are the limits to be honest, but especially, funding is the main issue I have.

Many of the methods you use for germinating seeds and propagating plants have been considered unorthodox, and this is undoubtedly one of the reasons behind your outstanding achievements. Did you find that your peers and colleagues were initially suspicious of your techniques and approach, or did you always feel supported in your methods?

Many of the methods you use for germinating seeds and propagating plants have been considered unorthodox, and this is undoubtedly one of the reasons behind your outstanding achievements. Did you find that your peers and colleagues were initially suspicious of your techniques and approach, or did you always feel supported in your methods?

I guess they are not that unorthodox after all, I will say is more in the lines of ‘if something does not work, let’s try something else’, which is a bit unorthodox but also the sensible thing to do in those cases. I guess it is always tricky to swim against the ‘mantras’ or certain situations where is easier to stick to ‘oh, it won’t work because it cannot be done’ but even when I can be a victim of this myself, I try to do my best to think that you never know if you don’t try. Horticulture is a bit complicated since there are so many aspects to take into account. Science has a big part to play in it, but there is also that bit that is more like cooking, not witchery, but no white lab coat stuff either.

In cultivation, there are too many factors, compost types, light, humidity, temperature, temperature fluctuation, pests, seasons, fertilizers, nutrient levels, and so on and so forth. It is very difficult sometimes to come from an answer as result of traditional science when trying to work out what are the best parameters for each of the 400,000 known species of plants. Good basic science knowledge is vital, but the capacity of guessing, the ability to acknowledge and correct your own mistakes, to be capable of observing very small changes in the general looking of a plant (which I guess involves good photographic memory) are equally important, throwing in a bit of ‘gut feeling’ as it can help too! Sometimes first you manage to grow a plant by ‘play it by the ear’ and if you succeed and manage to grow many, then you can do the empirical work in a more traditional scientific manner, but first, it has to grow!

Many of the processes you describe in your book are very labour intensive and appear to involve a certain amount of trial and error. With the understanding that time is of the essence for many of the species you work with, and that availability of seeds may be severely limited, how do you cope with the prolonged uncertainty and pressure that must surely exist when attempting to germinate seeds or propagate cuttings?

You try to do the obvious first. Sometimes you know that something works very well with that family, so you will try that first. If it does not work you need to come up with a theory of ‘what happened’ and then create a scenario that tries to prevent that situation happening again. When quantities of seeds are abundant, then that makes things easier since you can try many things at once. With very small quantities of material this is not possible, so you try to use safer options. Seeds that cannot be dried die if you dry them. Seeds that need to be dried to germinate can stay wet for a period after harvesting, so if the seeds have not been dried already, I may sow them without drying in a way that I can recover it later to try a dry, then wet method. If something can be undone, sometimes takes preference over some action that cannot be undone. If that fails, then try plan B. if everything fails and there is no more material, you had that experience so that next time something is available you can try something else. However, were the seeds non-viable? Were they too old? It can be a bit tricky to get the whole picture sometimes. There are quite a few general rules that help, the difficulty is to spot the exceptions to the rule. In these cases, experience is the mother of science and not the other way around, but then, you have to be sure that whatever change you want to do make sense from a natural science point of view.

You frequently state in your book that extinction is unacceptable. How do you feel about the proposals by some ecologists that our modifications to the planet have in fact stimulated evolution, and that extinctions and non-native invasions are just part of a natural process, albeit it one that our actions may have accelerated?

You frequently state in your book that extinction is unacceptable. How do you feel about the proposals by some ecologists that our modifications to the planet have in fact stimulated evolution, and that extinctions and non-native invasions are just part of a natural process, albeit it one that our actions may have accelerated?

First, I think that even if something is naturally going extinct, it should be preserved. No-one questions that we preserve items such as cathedrals or classic paintings under the excuse that ‘oh well, naturally they will fall apart and disintegrate in time’. They are an immeasurable resource and relevant part of our heritage. Regarding the invasive introductions…this is complex and cannot be summarized in a simple statement like the one above. There are species that naturalize and do not create a massive change, they just integrate as another item in the system, others occupy heavily pre-damaged ecosystems, so in fact, and they are a symptom rather than an illness of the damaged ecosystem. Look at Buddleia and its preference for cracks in concrete, brownfields, and decaying urban environments. Conservation is in a way altruistic (every species should have the right to live, just because it is a species), but also is an act of egoism and self-preservation because they are so useful to us in many ways. The more that we can keep, the more biodiverse the planet will be. As earlier stated, it is a very complex issue. What is the impact of invasive plants on CO2 absorption? Not sure what the answer to that is, but I bet that in some cases they are sequestering CO2, but not for all the species nor all the situations either. Avoiding extinctions should be always high on our agendas. We can aim to preserve many species long term, even if we still allow for lots of human changes taking place, but only if we can stop climate change and we manage the land properly. If we think ‘yeah, is all part of a natural process’ then we have to admit that burning fossil fuels is as natural as flying rabbits from Spain to the Antipodes, and also, that climate change will lead to a mass extinction but then, it will recover in a few million years later? No thanks, I rather keep the world as it is, beautiful and biodiverse, because guess what, nearly all of it is avoidable. Key word here: avoidable.

Animal conservationists often bemoan the fact that it is difficult to get the public interested in the “non-charismatic megafauna”. So, while the whales, tigers and pandas of the world have plenty of public attention and support, the plankton, toads and flies are often neglected. Do you feel this problem exists within the sphere of plant conservation too? Are the beautiful “charismatic” plants given attention over the less visually striking species? Or do you think that plants as a whole are neglected? As an extension of this, how do you think we should go about getting the public to care about the conservation of plants?

Animal conservationists often bemoan the fact that it is difficult to get the public interested in the “non-charismatic megafauna”. So, while the whales, tigers and pandas of the world have plenty of public attention and support, the plankton, toads and flies are often neglected. Do you feel this problem exists within the sphere of plant conservation too? Are the beautiful “charismatic” plants given attention over the less visually striking species? Or do you think that plants as a whole are neglected? As an extension of this, how do you think we should go about getting the public to care about the conservation of plants?

Firstly, yes, I think that plant conservation is low on people’s minds when compared with furry large animals. True that. But to be fair, a subspecies of the Javan rhino was declared extinct in Vietnam in 2011 and all the populations of this emblematic mammal are declining badly despite its cuteness, so there is work to be done with animals for sure.

I think we need to understand that plants are more important to our survival, and to the animal species survival than we think they do. With plants, we need to know them better before we can truly appreciate them. There is no Rhino without savannah and we need to look at the savannah more like a vegetation community rather than a background setting for Rhinos. Plants are the green glue that sticks the planet ecosystems together. We need to look at the system more, but systems are made of components and we cannot lose them if we want to keep the system going. It is always easier to attract funding and interest to showy plant species. Sad but true, but on the other hand, many stunning looking species are threatened and nothing much has been done. We need to raise the game in all departments of conservation. At the end of the day, it is the planet that we are protecting, not single species only. I have the feeling that avoiding plant extinction is easier than animal extinction, at least ex-situ. Yet, there are more instances of animals being reintroduced to the wild than plants. Sometimes, you need to introduce animals to recover the vegetation, i.e wolves rather than planting trees. Sometimes you may need to plant trees to reconnect two populations of large mammals. Fisheries rely heavily on seagrass and mangrove forest. Those two marine habitats fix massive amounts of CO2. Does global warming affects Panda’s favourite food? Rather than focus on animal vs plant conservation, we need to do this: to focus on single species so that they do not go extinct but also make sure that the worlds ecosystems are functioning. Easier said than done, but I refuse to accept that ‘cannot be done’. It is all avoidable.

Finally, is there a plant, either extant or presumed extinct, that you dream of seeing during your lifetime?

Only one? The trouble here is what to choose…there is so many things I do not want to miss in my life time. Never seen the redwood forest, I’ve never been to South Africa, Madagascar, New Guinea, Socotra…just to name a few incredible biodiverse areas that contain 100s of interesting ‘must see’ species. The discovery of a living fossil plant in the likes of Ginkgo or the Wollemy pine would always be very exciting…indeed the reappearance of an extinct species is always uplifting, however, if I have to choose, I go for the ‘extinction avoidance’. Mostly because, if I’m aware it is about to happen, and when it happens, it is so depressing. So I choose this: to produce and germinate seeds of Hyophorbe amaricaulis from Mauritius. Only one palm tree left, and decades of failures mean that is likely it will go extinct during my lifetime. I’m aware of this, and I cannot bear the thought of waking up one day to the news that a cyclone has split it in half.

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena is published by Penguin Books and is available from NHBS in hardback. The paperback version is due for publication in April 2018.

Keith Betton is a keen world birder, having seen over 8,000 species in over 100 countries. In the UK he is heavily involved in bird monitoring, where he is a County Recorder. He has been a Council member of both the RSPB and the BTO, currently Vice President of the latter.

Keith Betton is a keen world birder, having seen over 8,000 species in over 100 countries. In the UK he is heavily involved in bird monitoring, where he is a County Recorder. He has been a Council member of both the RSPB and the BTO, currently Vice President of the latter.

Your life as a researcher and CEO of the Manta Trust must be incredibly varied and exciting. I’m curious what a typical day in the life of Guy Stevens looks like. Or, if a ‘typical’ day is unheard of for you, can you describe a recent day for us?

Your life as a researcher and CEO of the Manta Trust must be incredibly varied and exciting. I’m curious what a typical day in the life of Guy Stevens looks like. Or, if a ‘typical’ day is unheard of for you, can you describe a recent day for us?