***** An emotional gut punch of a book

***** An emotional gut punch of a book

When you think Sixth Extinction, animals and plants such as the St. Helena olive, the Bramble Cay melomys, or the Christmas Island forest skink are unlikely to come to mind. And therein lies a problem: behind the faceless statistics of loss lie numerous stories of unique evolutionary lineages that have been snuffed out. In this emotional gut punch of a book, author and journalist Tom Lathan takes the unconventional approach of examining ten species that have gone extinct since 2000, nine of which you will likely never have heard of. Lathan momentarily resurrects them to examine what led to their loss and speaks to the people who tried to save them.

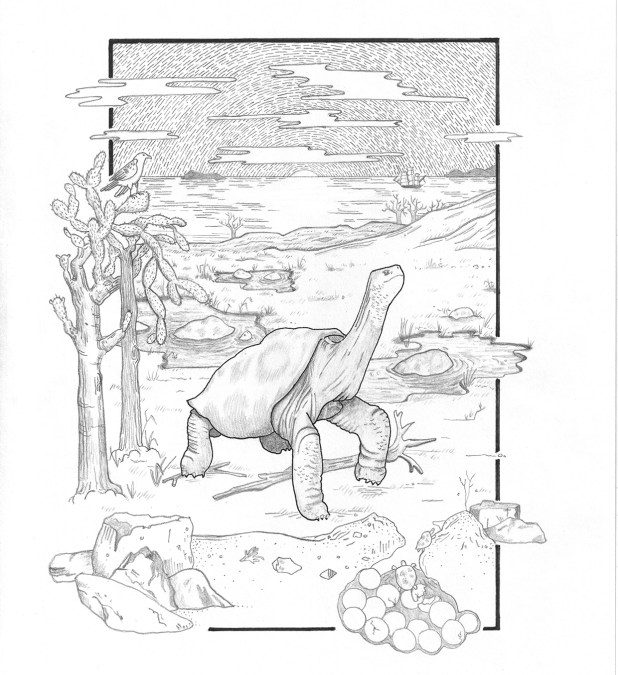

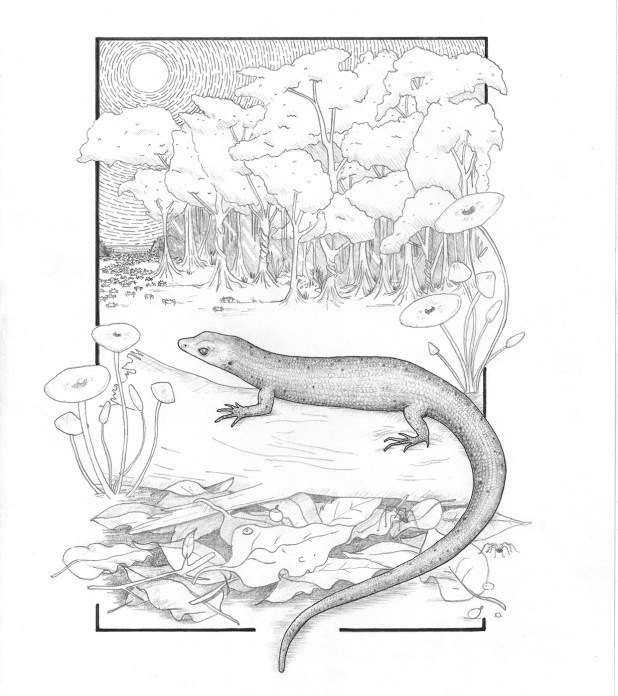

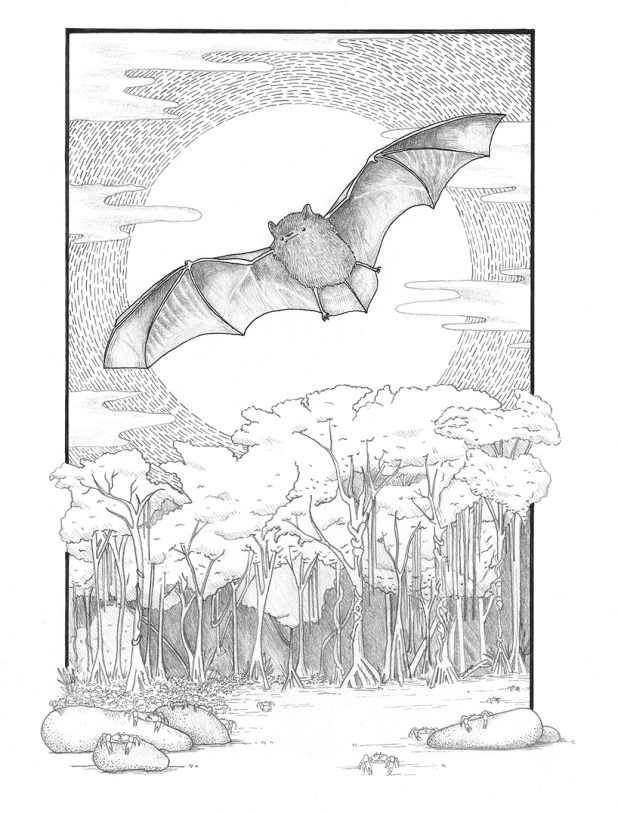

The one species and individual you are likely to have heard of is Lonesome George, the last Pinta Island tortoise, who received much media attention both in life and in death. The remainder are barely known outside of the small circle of conservationists who studied them. Of the unfortunately long list Lathan obtained from the IUCN, he has chosen a nicely balanced mix of species. Each chapter opens with a tastefully executed pencil-and-ink drawing by Lathan’s partner Claire Kohda. The geographic spread similarly includes organisms from around the globe (though no maps have been included, which would have been helpful). What unites these species is that they all lived, literally or functionally, on islands (environments prone to evolutionary experimentation and extinction), and they are no longer with us.

Each of the ten chapters mixes several elements such that, despite most chapters being quite long at 30–40 pages, all are very engaging. Lathan introduces what we know about their biology and how the frequent paucity of information frustrated subsequent attempts at captive breeding. By telling the stories of their discovery and formal description, Lathan answers his question of whether naming a species “is itself a life-giving act” (p. 28): it allows us to formulate conservation plans, making naming “the difference between life and death” (p. 29). Of course, species exist before we describe them, and his overview of their evolution is a potent reminder of this. It also highlights how, given enough time, organisms can reach remote islands and establish themselves there, despite the odds not being in their favour.

All of the above is relevant background information, but we are here for the stories of what went wrong. In the introduction, Lathan emphasizes just how incomplete our knowledge is: there is both a long queue of species awaiting assessment by the underfunded IUCN and an even larger pool of “dark extinctions” (p. 4): species that vanish before we even know of their existence. These stories are “a snapshot of extinction […] each a stand-in for other[s] that we will probably never know occurred” (p. 4). There is that importance of taxonomy again.

If extinctions of Pleistocene megafauna can reasonably be attributed to a mixture of human hunting and climate change, the fingerprint of more recent Holocene extinctions is clearly human. Lathan points out that our species is “one of the most potent agents of ecological destruction, regardless of time, place, or culture” (p. 135). For instance, the arrival of native Polynesians to Hawai’i already triggered a wave of extinction, such that the arrival of Europeans “was more like a passing of the baton in an ecocidal relay race” (p. 136). That said, in his next breath he immediately recognizes that European colonialism cranked up extinction to eleven—it is a good example of Lathan’s balanced reporting. What follows is the usual litany of rapacious resource extraction that destroys natural habitats and the accidental or purposeful introduction of invasive species. The two often work in tandem.

The strongest suit of Lost Wonders is the nearly 50 interviews with scientists, conservationists, hobbyists, and others whose first-hand experiences and frustrations imbue this work with much pathos. There are stories of species slipping through our hands as their habitats vanished (e.g. the Bramble Cay melomys, a rat, or the Alagoas foliage-gleaner, a bird); of ignored warnings, bureaucratic red tape, and apprehensive committees delaying meaningful action (e.g. the Polynesian tree snail P. labrusca or the Christmas Island pipistrelle); and of captive breeding efforts failing (e.g. the Mexican Catarina pupfish). By asking how the people involved experienced witnessing extinction, each chapter delivers an emotional gut punch that, I will not lie, sometimes brought me to tears. Some people still struggle talking about it, even a decade or more later, breaking down during their interviews. Others describe feelings of grief, depression, and loneliness, unable to truly share with others what they experienced. Lathan himself in his epilogue expresses his astonishment at “their capacity to articulate the profundity of what they had witnessed” and wonders out loud: “When a million years of evolution is extinguished right in front of you, what words suffice to describe this moment?” (p. 351).

Taking a step back to compose myself I do, however, have two points of criticism; or, if not criticism, two points I feel have been omitted. First, there is the proximate question of whether trying to save a species at all costs is always the best use of the limited time, money, and other resources available for conservation. Not everybody agrees it is, and e.g. Inheritors of the Earth provocatively argued that island species are evolutionary dead ends, vulnerable to invasion. Are resources better spent on populations that still stand a decent chance? A counterargument could be made that, yes, these attempts *are* worthwhile because we learn how to improve our protocols, techniques, and technologies for the inevitable next extinction. My point is that Lathan does not broach these questions here. I would have loved for him to wrestle with these and put them to his interviewees. Second, there is the ultimate question of what it would take to turn the tide of extinction, of what such a world would look like. I judge him less harshly on this because very few authors seem willing to mention the root causes that got us here. His interviewees gave him several openings at broaching thorny topics that he did not pursue. This is another set of questions where both his views and those of his interviewees could have further enriched the book.

Taking a step back to compose myself I do, however, have two points of criticism; or, if not criticism, two points I feel have been omitted. First, there is the proximate question of whether trying to save a species at all costs is always the best use of the limited time, money, and other resources available for conservation. Not everybody agrees it is, and e.g. Inheritors of the Earth provocatively argued that island species are evolutionary dead ends, vulnerable to invasion. Are resources better spent on populations that still stand a decent chance? A counterargument could be made that, yes, these attempts *are* worthwhile because we learn how to improve our protocols, techniques, and technologies for the inevitable next extinction. My point is that Lathan does not broach these questions here. I would have loved for him to wrestle with these and put them to his interviewees. Second, there is the ultimate question of what it would take to turn the tide of extinction, of what such a world would look like. I judge him less harshly on this because very few authors seem willing to mention the root causes that got us here. His interviewees gave him several openings at broaching thorny topics that he did not pursue. This is another set of questions where both his views and those of his interviewees could have further enriched the book.

The above suggestions would have been cherries on the cake but, as it stands, the proverbial cake is both edible and rich. Lost Worlds is an incredibly moving book that tugs at the heartstrings and draws on an impressive number of interviews. These eyewitness stories are a powerful reminder that behind each reported extinction lies a tremendous amount of work, and the loss of a unique way of life on this planet.

Lost Wonders is available from our bookstore here.

Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Chapter 3 bundles together research on numerous other senses, including ones familiar (smell, taste, and hearing) and unfamiliar to us (perception of polarised light, Earth’s magnetic field, and electric fields). The antennae of bees, in particular, are marvels; Chittka likens them to a biological Swiss army knife, packing numerous different sense organs into two small appendages. Tightly connected to sensory biology is how this incoming information is processed in the brain, though Chittka postpones discussing neurobiology to chapter 9. He describes the discovery and function of different brain areas and highlights the work of Frederick Kenyon who would inspire the better-remembered Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Thanks to them, we now understand that brains consist of numerous specialised nerve cells. Though the bee brain is small, Chittka argues that size is a poor predictor of cognitive skills; it is the wiring of neurons that matters. Rather than be surprised that small-brained insects such as bees can do so many clever things, Chittka instead tickles the reader with the opposite question: “Why does any animal need as large a brain as a bee’s?” (p. 153).

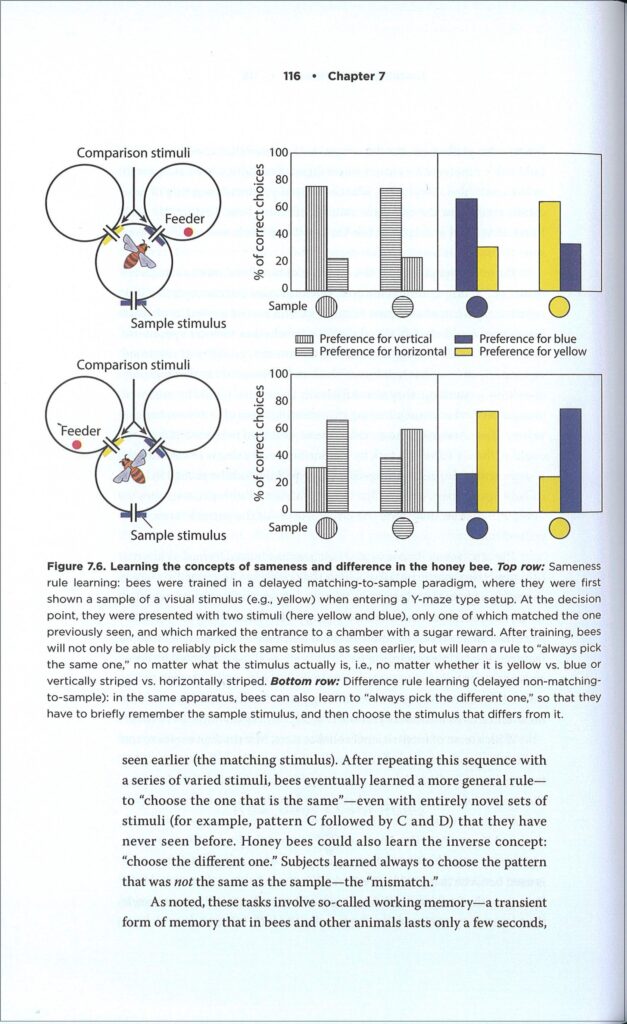

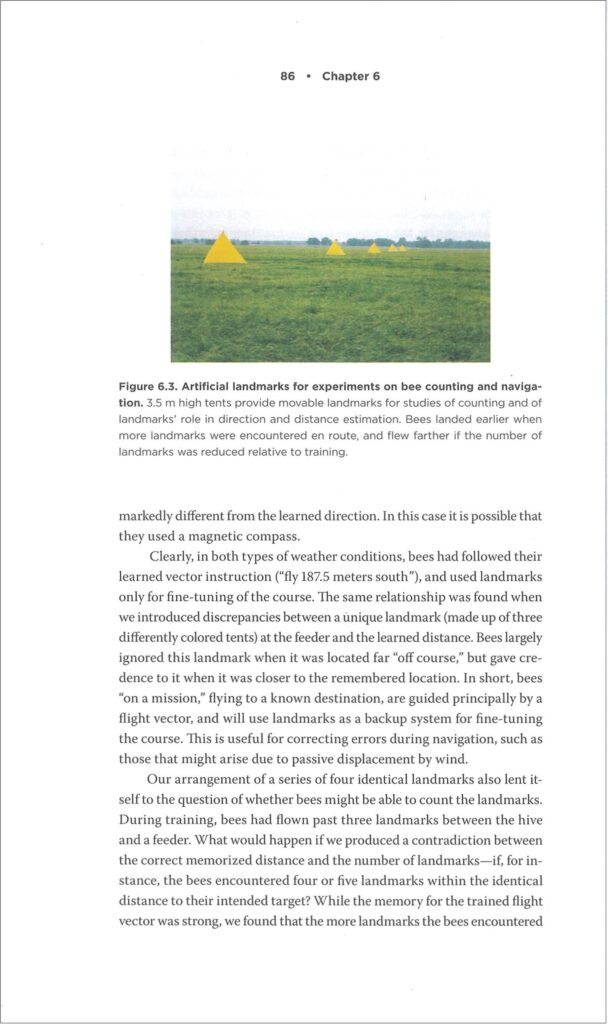

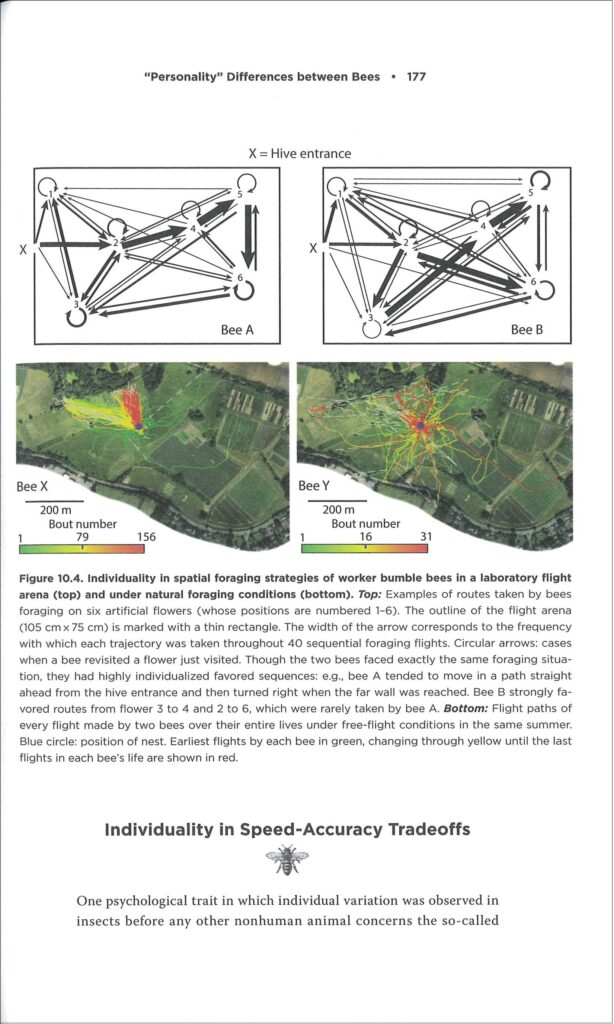

Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Chapter 3 bundles together research on numerous other senses, including ones familiar (smell, taste, and hearing) and unfamiliar to us (perception of polarised light, Earth’s magnetic field, and electric fields). The antennae of bees, in particular, are marvels; Chittka likens them to a biological Swiss army knife, packing numerous different sense organs into two small appendages. Tightly connected to sensory biology is how this incoming information is processed in the brain, though Chittka postpones discussing neurobiology to chapter 9. He describes the discovery and function of different brain areas and highlights the work of Frederick Kenyon who would inspire the better-remembered Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Thanks to them, we now understand that brains consist of numerous specialised nerve cells. Though the bee brain is small, Chittka argues that size is a poor predictor of cognitive skills; it is the wiring of neurons that matters. Rather than be surprised that small-brained insects such as bees can do so many clever things, Chittka instead tickles the reader with the opposite question: “Why does any animal need as large a brain as a bee’s?” (p. 153). What clever things do bees do, you ask? That is the subject of the preceding five chapters where Chittka surveys a large body of behavioural research. Honey bees are famous for their waggle dance by which they communicate the location of flowers but also, this was news to me, the location of potential nest sites when the swarm relocates. But Chittka discusses more, much more: how bees navigate space using landmarks, show a rudimentary form of counting, solve the travelling salesman problem, learn to extract nectar from complex flowers, learn when to exploit certain flowers (and when to ignore them), and learn new tricks by observing other bees. But what about instinct, something most behaviours were traditionally ascribed to? He has some insightful comments on this: “even the most elemental behavior routines need to be refined by learning: instinct provides little more than a rough template” (p. 50). What really made me fall off my chair is that bees have long been outsmarting researchers in choice experiments. Many behavioural experiments take the form of choice tests, where bees need to pick between two locations or objects that differ in e.g. colour or shape with one option containing a sugary solution as a reward. Bumblebees would simply be lazy and check out both options in random order. Until, that is, protocols were modified by adding a bitter-tasting solution to the wrong choice as a penalty.

What clever things do bees do, you ask? That is the subject of the preceding five chapters where Chittka surveys a large body of behavioural research. Honey bees are famous for their waggle dance by which they communicate the location of flowers but also, this was news to me, the location of potential nest sites when the swarm relocates. But Chittka discusses more, much more: how bees navigate space using landmarks, show a rudimentary form of counting, solve the travelling salesman problem, learn to extract nectar from complex flowers, learn when to exploit certain flowers (and when to ignore them), and learn new tricks by observing other bees. But what about instinct, something most behaviours were traditionally ascribed to? He has some insightful comments on this: “even the most elemental behavior routines need to be refined by learning: instinct provides little more than a rough template” (p. 50). What really made me fall off my chair is that bees have long been outsmarting researchers in choice experiments. Many behavioural experiments take the form of choice tests, where bees need to pick between two locations or objects that differ in e.g. colour or shape with one option containing a sugary solution as a reward. Bumblebees would simply be lazy and check out both options in random order. Until, that is, protocols were modified by adding a bitter-tasting solution to the wrong choice as a penalty. As mentioned above, this book is focused. If you enjoy reading about the facts and the study system with minimal (autobiographical) diversions, Chittka has got you covered. The only digression he allows himself is to include biographical details of older generations of scientists. This includes inspiring tales such as Karl von Frisch who described the honey bee waggle dance and later barely escaped being dismissed from his post by the Nazis. And look out for repeat appearances of Charles Turner, a now largely forgotten African American scientist who published pioneering work despite having been denied a professorship based on his ethnicity. But there are also tragic stories such as Kenyon’s, who snapped under pressure of not securing a permanent job and was incarcerated in a lunatic asylum where he died more than 40 years later, alone and forgotten. Chittka includes occasional quotations from historical literature to show that “many seemingly contemporary ideas about the minds of bees had already been expressed, in some form, over a century ago” (p. 15).

As mentioned above, this book is focused. If you enjoy reading about the facts and the study system with minimal (autobiographical) diversions, Chittka has got you covered. The only digression he allows himself is to include biographical details of older generations of scientists. This includes inspiring tales such as Karl von Frisch who described the honey bee waggle dance and later barely escaped being dismissed from his post by the Nazis. And look out for repeat appearances of Charles Turner, a now largely forgotten African American scientist who published pioneering work despite having been denied a professorship based on his ethnicity. But there are also tragic stories such as Kenyon’s, who snapped under pressure of not securing a permanent job and was incarcerated in a lunatic asylum where he died more than 40 years later, alone and forgotten. Chittka includes occasional quotations from historical literature to show that “many seemingly contemporary ideas about the minds of bees had already been expressed, in some form, over a century ago” (p. 15).