***** A nuanced and detailed overview

***** A nuanced and detailed overview

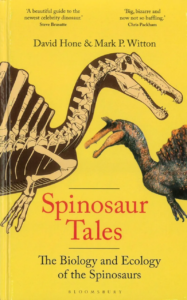

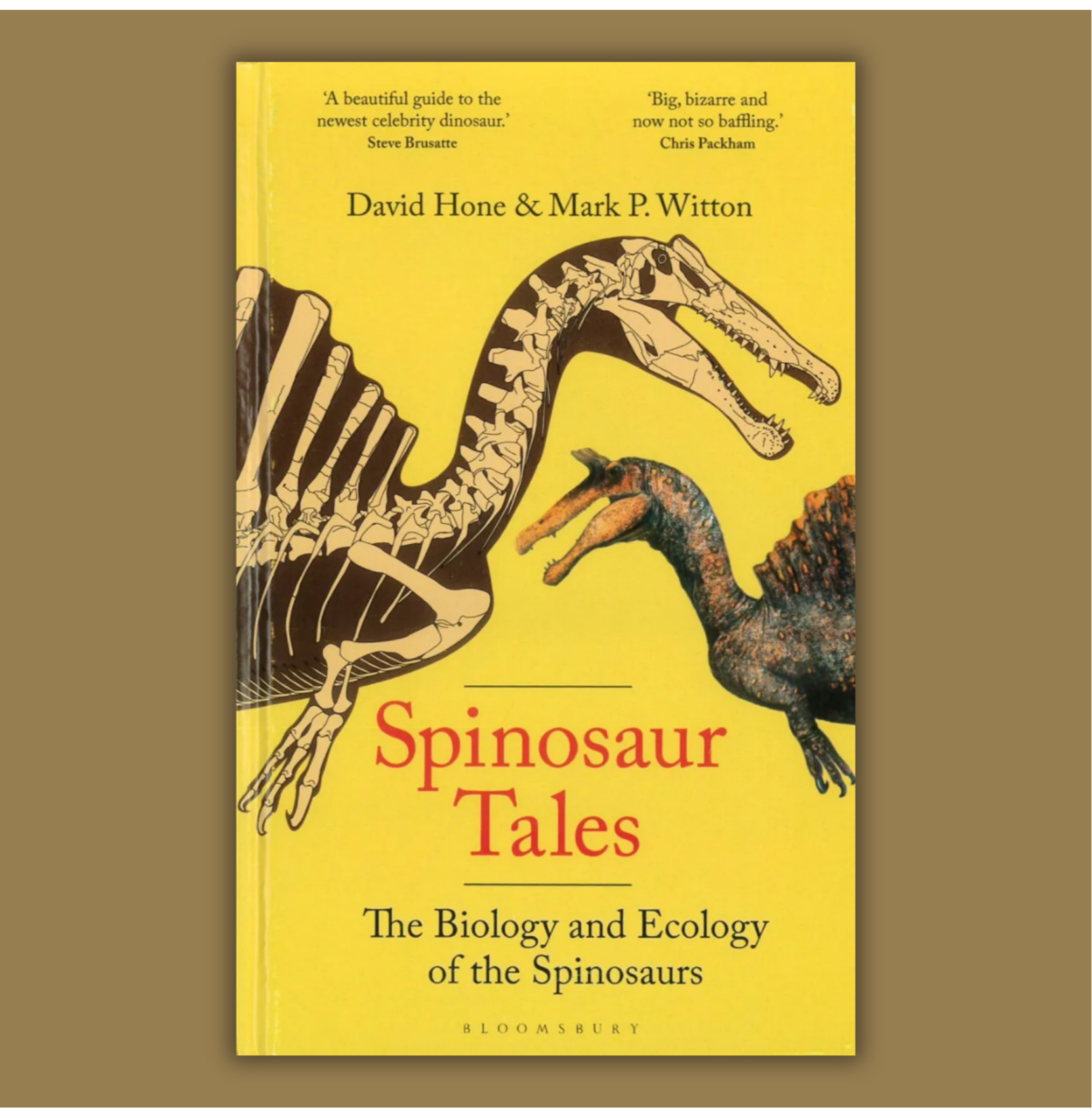

These fish-eating and sail-backed (well, some of them) predatory dinosaurs are as enigmatic as they are controversial, and writing a book about them means navigating both fragmentary remains and strongly held opinions. So, who better to tackle this challenge than two of the best names in the business? This thoughtful book brings together palaeontologists Dave Hone and Mark P. Witton to discuss everything we do and do not know about spinosaurs.

Hone & Witton are, I think, exceptionally well-suited to write a book about a controversial group where so much is still unknown or subject to revision. Next to a track record of popular science books on dinosaurs, both authors stand out for their careful and nuanced views. Spinosaur Tales is logically structured and flows well. In their preface, the authors pre-empt concerns about this book becoming obsolete by acknowledging that they “can only present a snapshot of spinosaur science as it races along in the winter of 2024” (p. 8). This is followed by twelve chapters that take a detailed tour through research on the family Spinosauridae. Rather than a chapter-by-chapter summary, I want to focus on why spinosaurs are such a controversial group to begin with, how Hone & Witton tackle this, and how they have written an outstanding book in the process.

One of the foremost reasons why spinosaurs are such a challenging group is their fragmentary fossil record: we have not a single complete skeleton. Partial skeletons are or were (Spinosaurus) available for some species, but many currently named species are contentious, based on fragmentary remains such as loose teeth, bits of jaw, and some vertebrae. Despite having been named over a century ago, “we are still forming the foundation of our knowledge” (p. 23).

Though this situation is not unique to spinosaurs, there are two further complicating factors. I just mentioned Spinosaurus in the past tense, and this leads into a remarkable bit of history in that Stromer’s original 1915 Egyptian Spinosaurus aegyptiacus fossil was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid during WWII. All that remains are his drawings and descriptions, which continues to frustrate research to this day. The second problem is that some recent material has been bought from commercial fossil collectors who frequently do not record the geological context (i.e. the geological stratum and thus the age) of their finds and often only excavate the parts they can sell. The lack of standardised methods during such excavations means that vital scientific information continues to be lost, further hindering research.

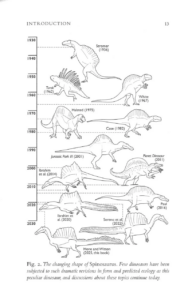

Given these difficulties, our understanding of spinosaurs changes continuously. While certain past ideas might seem like howlers today, Hone & Witton provide nuanced historical context to clarify that they were reasonable given what we knew at the time. When described in 1986, Baryonyx walkeri was initially dismissed as a spinosaur. Similarly, a crocodilian origin for spinosaurs was long considered a possibility, based on the superficial anatomical resemblances between their skulls. A different sort of challenge is the celebrity status that spinosaurs attained in the 2000s, partially thanks to the movie Jurassic Park III, and partially to a relative glut of new finds. Spinosaur research is now newsworthy and thus a frequent subject of hype and exaggerated controversy. Online communities of dinosaur enthusiasts closely follow every academic volley and riposte and engage in “strongly worded discourse about their implications” (p. 18). A good example of this was the public unveiling of a new specimen from Morocco in 2014 that pushed the idea that Spinosaurus swam. Hone & Witton patiently but firmly consider this idea from multiple angles and show that, though we have several lines of evidence that Spinosaurus ate fish, it would have made a poor swimmer.

A consequence of this newfound fame is that spinosaur researchers are faced with questions “that demand simple answers, yet warrant complex, nuanced responses” (p. 287). I think that this, in a nutshell, beautifully describes what Hone & Witton have achieved here: Spinosaur Tales is a book-length exercise in nuanced responses. An important component of this, vital when writing a popular science book, is to familiarise readers with those aspects of palaeontology that its practitioners often take for granted. Most books fail to explain that the concept of a species differs in biology and palaeontology, something Hone & Witton thankfully clarify. Figuring out how many fossil species were distinct biological entities and whether the group was as diverse as we think is difficult. Similarly, I often feel that many books fail to emphasise that “fossilisation is a biasing, distorting process […] giving us partial, often skewed insights into ancient floras and faunas” (p. 107). The authors repeatedly remind you of the many caveats when interpreting this imperfect and incompletely sampled record.

Finally, the authors deserve praise for their progressive attitudes towards, and delicate handling of, the discipline’s historical baggage. Many past expeditions that collected important spinosaur material were “classic example[s] of scientific colonialism” (p. 53). There is similarly controversy over two proposed species from Brazil. With some remains now residing in a German museum, Hone & Witton are in favour of repatriation, both to clear up the taxonomic issue, but also to “rectify an injustice inflicted against Brazilian fossil heritage” (p. 51). And what to do with a historical figure such as naturalist Sir Richard Owen? Handle him delicately, I guess. Hone & Witton walk the fine line between acknowledging that he was at times a deeply unpleasant person who engaged in all sorts of skulduggery to advance his career, without erasing his significant achievements.

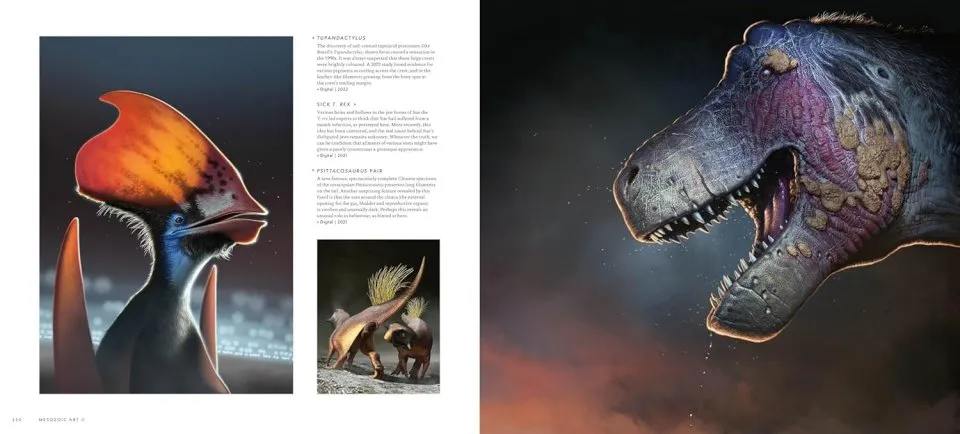

Witton is a professional palaeoartist, and this book benefits from a diverse selection of his illustrations. There is an eight-page colour plate section showcasing his well-known naturalistic artwork, while the diagrams of skulls and bones show his skills as a draughtsman. What caught my eye, however, are his black-and-white drawings that show life reconstructions and sit somewhere between doodles and comic book art. They reveal a different side to his artwork that I was not yet familiar with.

Overall, Spinosaur Tales is a thoughtful and accessible book about these enigmatic dinosaurs. It both explains why spinosaurs are such a difficult group to study, and then rises to the challenge by presenting a nuanced overview of what we know, what we can reasonably infer, and what is spin.

***** Still as captivating and entertaining as in 1988

***** Still as captivating and entertaining as in 1988

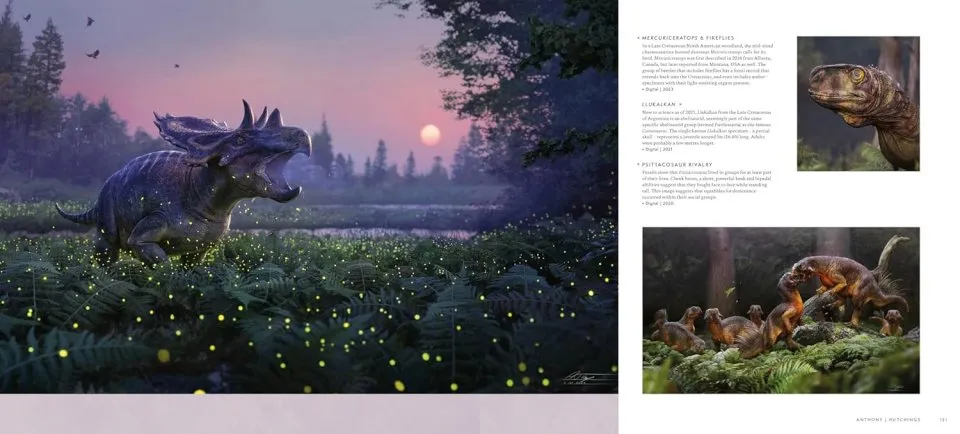

***** A remarkably diverse collection of the very best of current palaeoart

***** A remarkably diverse collection of the very best of current palaeoart

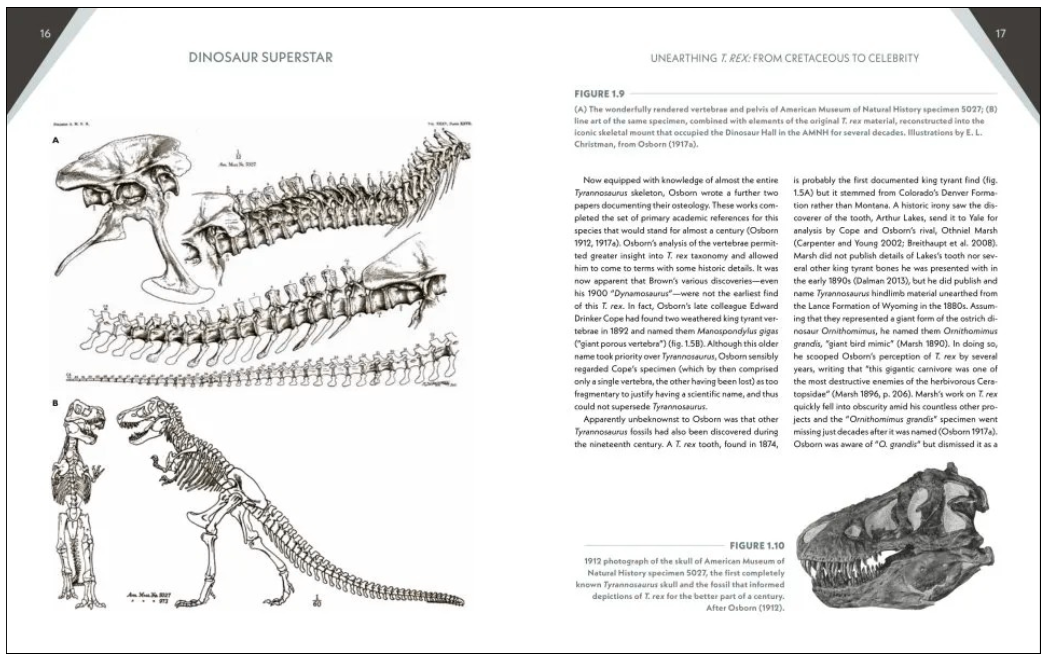

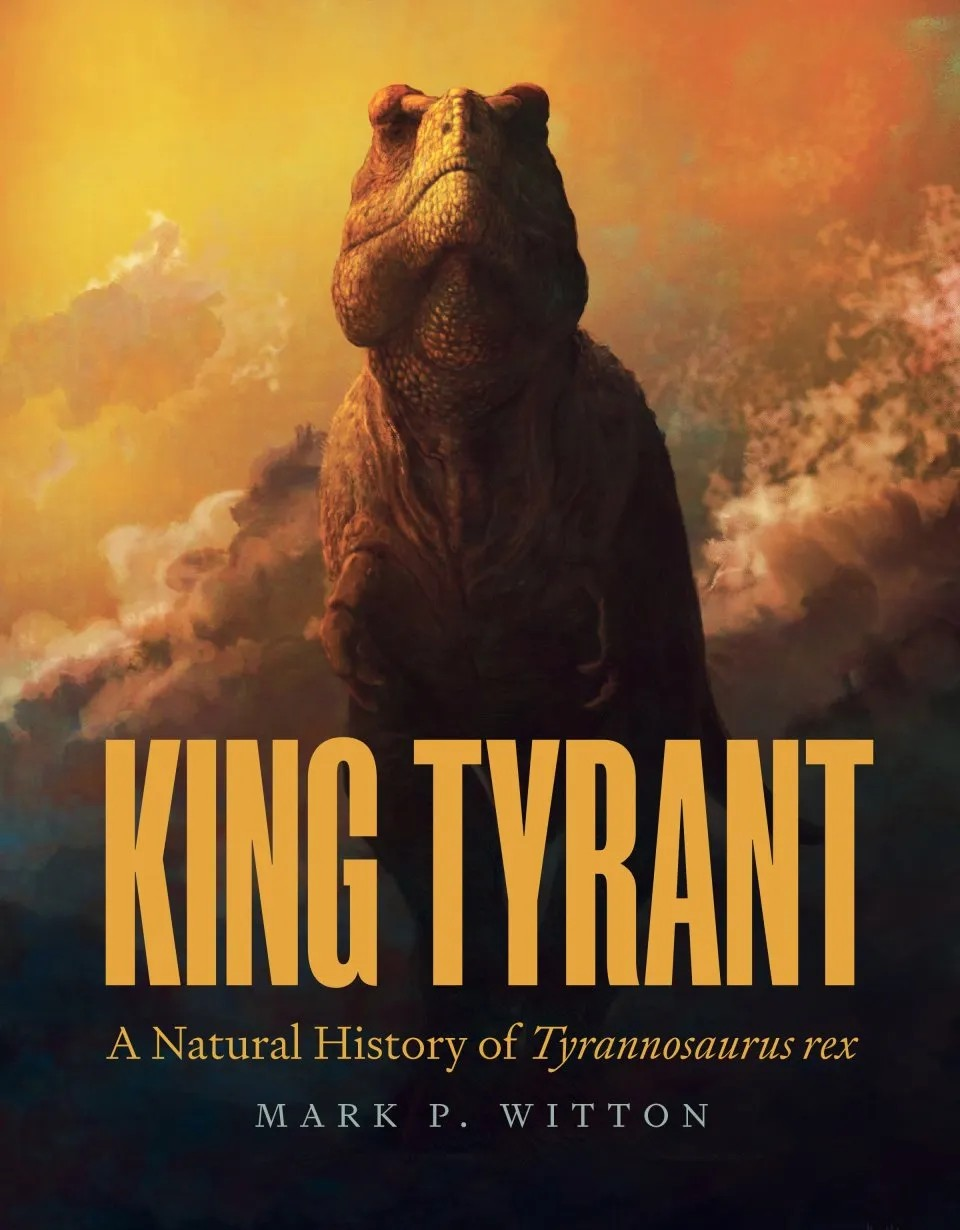

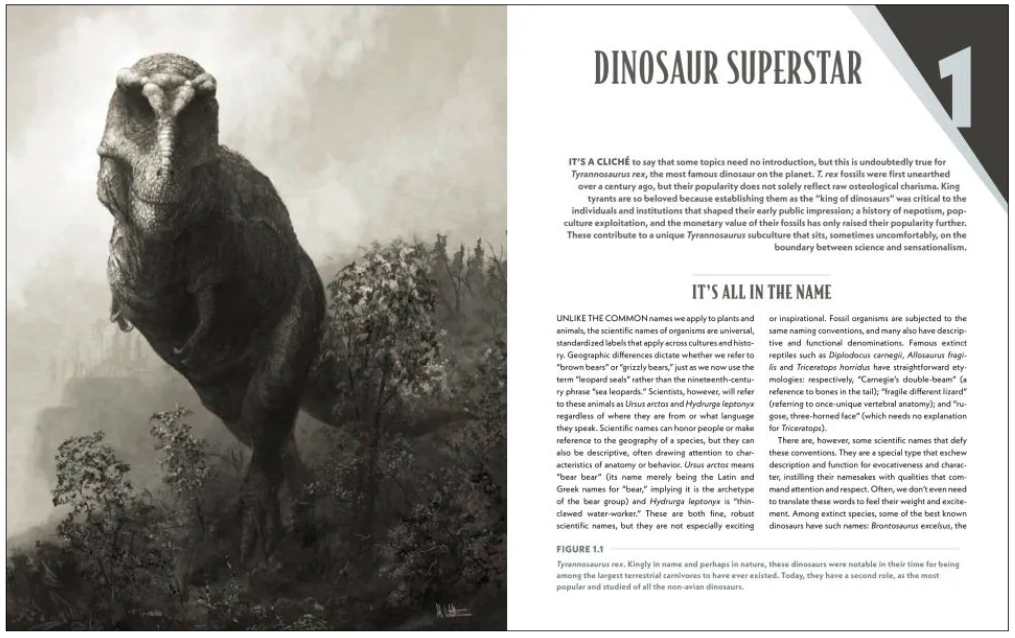

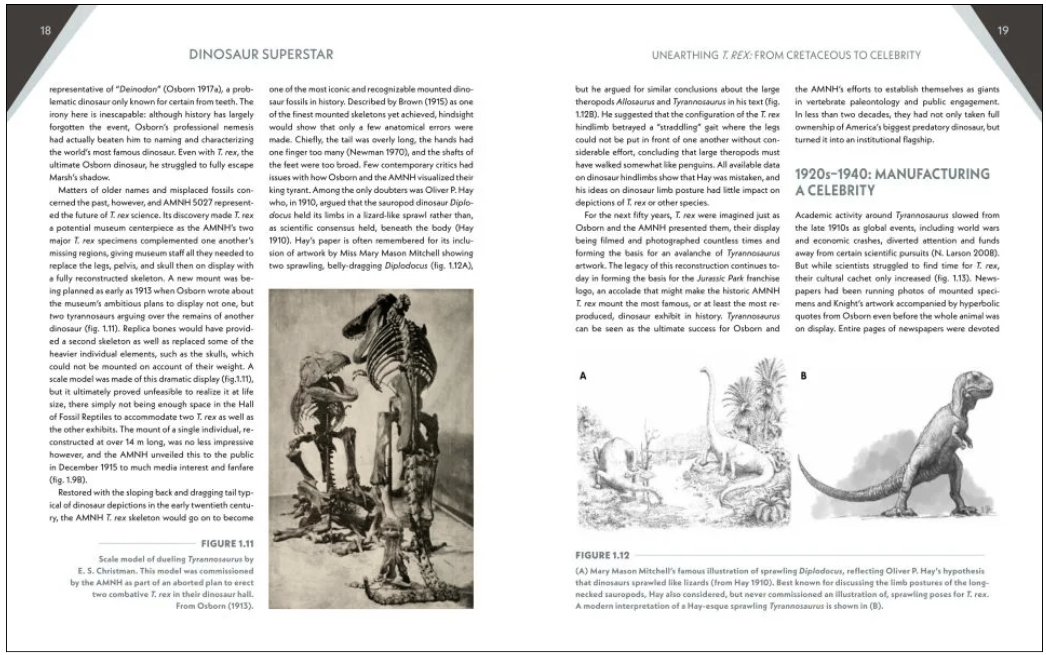

Given how frequently the name T. rex crops up, you might even get a bit annoyed: not you again! All the more reason to read this book. Witton is acutely aware that a veritable subculture has grown up around this one species that “sits, sometimes uncomfortably, on the boundary between science and sensationalism” (p. 1). These popular depictions, often carrying with them an air of scientific authority, bleed into people’s consciousness, creating something less of a dinosaur and more of a chimaera, with traits both exaggerated and fictional. One of Witton’s most important goals with King Tyrant is to “deconstruct hype and controversy” (p. 41). The first chapter daringly combines a précis of the first century of research with an examination of the sociological side. How did this particular species become palaeontology’s rock star? It is a fascinating history that starts at the American Museum of Natural History who promoted it to attract large crowds. It was “proverbial lightning in a bottle” (p. 278), with an influential legacy that lasts to this day in movies, documentaries, and merchandise. And yet, popular depictions “have nothing on what science tells us about the reality of Tyrannosaurus rex” (p. 279).

Given how frequently the name T. rex crops up, you might even get a bit annoyed: not you again! All the more reason to read this book. Witton is acutely aware that a veritable subculture has grown up around this one species that “sits, sometimes uncomfortably, on the boundary between science and sensationalism” (p. 1). These popular depictions, often carrying with them an air of scientific authority, bleed into people’s consciousness, creating something less of a dinosaur and more of a chimaera, with traits both exaggerated and fictional. One of Witton’s most important goals with King Tyrant is to “deconstruct hype and controversy” (p. 41). The first chapter daringly combines a précis of the first century of research with an examination of the sociological side. How did this particular species become palaeontology’s rock star? It is a fascinating history that starts at the American Museum of Natural History who promoted it to attract large crowds. It was “proverbial lightning in a bottle” (p. 278), with an influential legacy that lasts to this day in movies, documentaries, and merchandise. And yet, popular depictions “have nothing on what science tells us about the reality of Tyrannosaurus rex” (p. 279). T. rex, more than any other species, attracts a lot of fringe ideas from inside and outside of academia, and Witton leaves no rock unturned. On the one hand, there are the minority views and “non-troversies” (thanks Witton, I am stealing that brilliant term) that get far too much airtime, such as the existence (or not) of a dwarf species, “Nanotyrannus“, or the scavenging hypothesis, the notion that T. rex was a scavenger rather than a hunter. Needless to say, neither idea curries much favour among professionals. On the other hand, actual scientific debates are often ignored by the press. Opinions are divided on whether dinosaurs were already on their way out before the asteroid impact or were still in their prime. Witton provides the best overview of this topic that I have read so far.

T. rex, more than any other species, attracts a lot of fringe ideas from inside and outside of academia, and Witton leaves no rock unturned. On the one hand, there are the minority views and “non-troversies” (thanks Witton, I am stealing that brilliant term) that get far too much airtime, such as the existence (or not) of a dwarf species, “Nanotyrannus“, or the scavenging hypothesis, the notion that T. rex was a scavenger rather than a hunter. Needless to say, neither idea curries much favour among professionals. On the other hand, actual scientific debates are often ignored by the press. Opinions are divided on whether dinosaurs were already on their way out before the asteroid impact or were still in their prime. Witton provides the best overview of this topic that I have read so far.